Even experienced clinicians know surprisingly little about bipolar II disorder (BD II), despite its inclusion as a distinct entity in DSM since 1994. An abundance of studies supports conceptualization of BD II as a unique phenotype within the bipolar illness spectrum, although many fail to recognize it as distinct disorder apart from bipolar I disorder (BD I).

Alternatively, BD II is considered a “lesser form” of BD I, despite numerous studies showing comparable illness severity and risk of suicide in these two BD subtypes. Perhaps because of its under-recognition, treatment studies of BD II are limited, and too often results from studies of patients with BD I are simply applied to those with BD II with no direct evidence supporting this practice. BD II is an understudied and unmet treatment challenge in psychiatry.

In this review, we will provide a broad overview of BD II including differential diagnosis, course of illness, comorbidities, and suicide risk. We will summarize treatment studies specific to BD II, identifying gaps in the literature. This review will reveal similarities between BD I and II, including suicide risk and predominance of depression over the course of illness, but also differences between the phenotypes in treatment response, for example to antidepressants.

Diagnosis History

Alternating states of mania and melancholia are among the earliest described human diseases, first noted by ancient Greek physicians, philosophers, and poets. Hippocrates (460-337 B.C.E.), who formulated the first known classification of mental disorders, systematically described bipolar mood states: melancholia, mania, and paranoia. More than two millennia later, Emil Kraepelin, recognized as one of the founders of modern psychiatry, described manic-depressive illness as a singular disease characterized by alternating cycles of mania or melancholia. However, Kraepelin was more focused on mood changes and cycling than the polarity of episodes per se. Thus, his concept included what we now term recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD). Nevertheless, his and other formulations from this period provide background for our modern concepts of bipolar disorder, differentiating it from unipolar depression (MDD and related disorders).

The hiding in plain sight of patients with BD II was brought to awareness by David L. Dunner, M.D., in the 1960s. When examining a cohort of individuals with mood disorders in a study by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), he identified a subgroup of patients with recurrent episodes of depression who also had a history of at least one period of hypomania and a strong family history of bipolar disorder. This subgroup was found to have a different course of illness compared with those with recurrent depression and a history of mania (BD I). Thanks to this work, BD II was recognized as a distinct disorder, separate from BD I. It finally entered the DSM lexicon in 1994 in DSM-IV and was added to ICD-10 even more recently.

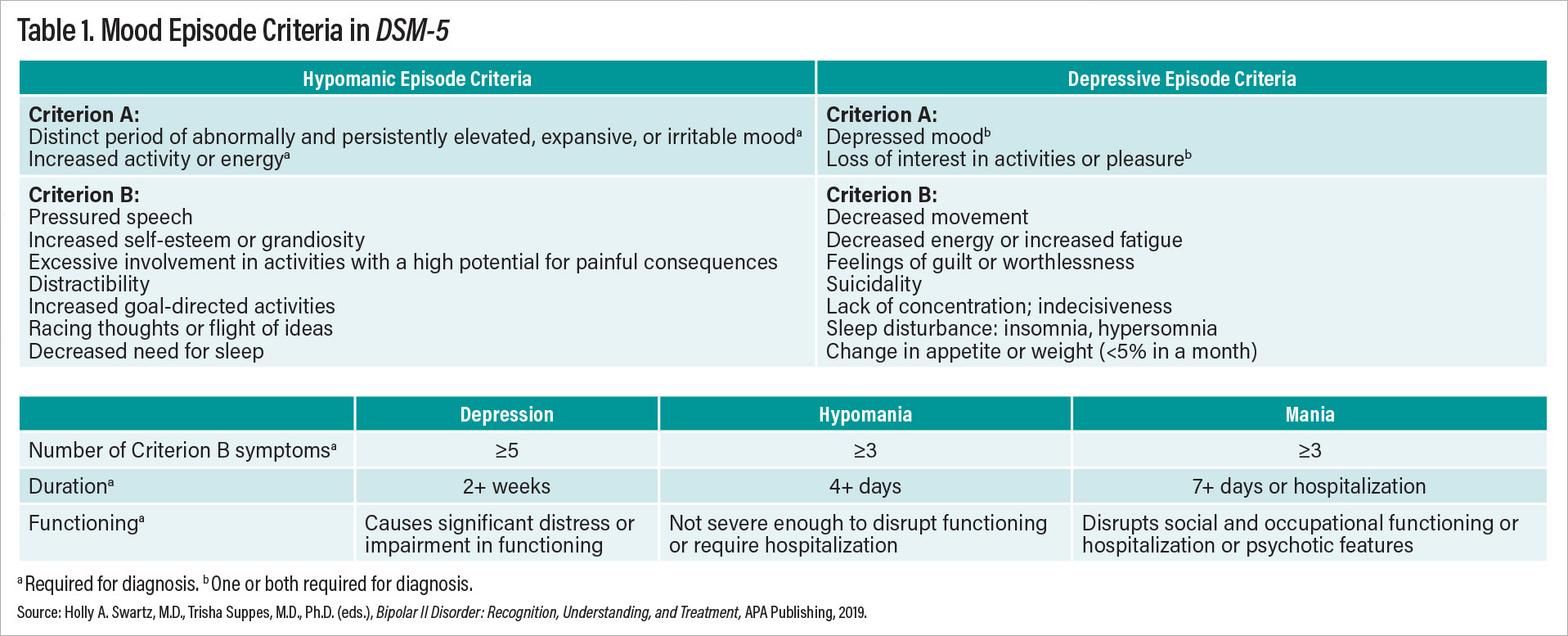

Conceptualization of bipolar disorders continues to evolve as the field learns more; for example, changes were made to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for BD such that Criteria A for both mania and hypomania now include increased energy as well as elevated or irritable mood (see Table 1). Thus, BD II is now recognized as a disorder of energy as well as mood.

DSM focuses on categorial diagnoses—that is, thresholds for absence or presence of disease. In parallel to this framework, many have argued for considering bipolar disorders along a continuous spectrum of illness. Thus, the term bipolar spectrum is used to describe both the spectrum of severity across BD symptoms as well as combinations of mood symptoms with manic/hypomanic and depressive components. Some refer to BD II as a part of the bipolar spectrum. These concepts reflect a growing awareness that dimensional descriptions of mood disorders may better map onto continuous biological markers of disease, compared with DSM’s categorical approach, but the debate about diagnostic boundaries and disease etiology continues. Importantly, conceptualizations of BD as a spectrum condition versus discrete diagnostic categories (that is, BD I or BD II) are not mutually exclusive but rather speak to ongoing efforts to understand and best describe the phenomenology of BD.

Differential Diagnosis

The validity of BD II as a separate disorder has been reified through multiple empirical studies. The clinical diagnosis is reliably separable from BD I, as seen in APA clinical trials preparing for DSM-5 and in careful clinical interviews. In DSM-5 field trials to assess reliability of diagnoses, BD I was among the most recognizable, but BD II fell in the acceptable range and well above MDD as a reliable diagnostic entity. Family studies also support the diagnosis of BD II as an independent entity with distinct familial heritability, according to a 1976 study by Dunner et al. and a 1990 study by J. Raymond DePaulo, M.D., et al., and the authors of this report. Finally, genetic studies have found correlations suggesting the heterogeneity between BD I and BD II is “nonrandom,” supporting the concept of distinct conditions.

BD II diagnosis requires at least one lifetime hypomanic episode and one major depressive episode. Despite clarity of BD II diagnostic criteria, clinicians struggle to accurately identify it in practice. BD II is often either missed or incorrectly diagnosed, resulting in an over 10-year delay in diagnosis. Difficulties in accurate diagnosis arise from several sources. First, DSM-5 criteria for the depressive phase of BD II are identical to those required for a major depressive episode, which make BD II and MDD cross-sectionally indistinguishable. This is particularly notable as MDD diagnoses make up a substantial percent of the incorrect diagnoses for patients with BD II. Second, hypomania, which by definition is a less severe form of mania, may be difficult for patients to distinguish from a “normal” mood state when accompanied by extra energy and good mood. Third, mixed hypomanic mood states are very common in BD II, and in fact more common than euphoric hypomanic states. Mixed mood states are characterized by the presence of symptoms of opposite polarity during a depressive or hypomanic episode. In a mixed hypomania, patients might believe they are simply irritable and angry in the context of depression rather than recognizing the additional hypomanic symptoms warranting a diagnosis of mixed hypomanic state. Finally, patients rarely present for treatment in the midst of a hypomanic episode, a mood state that is either perceived as ego-syntonic or simply not identified as part of their illness during mixed hypomania.

The primary reason patients with BD II seek care is depression. Depression dominates the course of BD II, both in the early and late stages. However, retrospectively identifying episodes of hypomania during a depressive episode can be challenging. Further, many individuals see hypomania (either the euphoric or mixed variant) as part of “normal” mood rather than part of a bipolar spectrum, contributing to misreporting of mood episodes. Especially after unrelenting episodes of depression, it is understandable that many would perceive hypomania as a return to baseline. However, under-recognition of hypomania contributes to incorrect diagnoses. In sum, many individuals with BD II fail to recall, recognize, or report histories of hypomania, leading to an MDD (mis)diagnosis.

In psychiatry, all diagnoses are a one-way road. Individuals who have ever met criteria for a manic episode will continue to carry the diagnosis of BD I—even without further manic episodes. Similarly, patients who have a distant episode of hypomania and at least one prior major depressive episode would be considered to have BD II disorder, even in the absence of additional hypomanic episodes that meet symptom and duration criteria. Thus, accurate diagnosis of BD II relies on careful history taking. To improve diagnostic acumen, it is essential that clinicians systematically screen all patients with MDD for BD and ask careful questions about prior episodes of hypomania.

Course of Illness and Comorbidity

Kraepelin noted before the medication era that the course of illness for patients with BD generally progresses into more persistent and severe depression with aging. While he was primarily referring to manic-depressive illness, which we would call BD I today, the same principle applies to patients with BD II. In the NIMH collaborative study by Lewis Judd, M.D., et al., which included long-term follow-up of up to 20 years, patients with BD II experienced a course of illness characterized by more depressive episodes and fewer well intervals over time.

There is a longstanding debate in the literature whether patients with BD II suffer the same impairments and risks as those with BD I. BD II was previously—and incorrectly—labeled a “less severe” version of BD I. In fact, studies consistently show comparable disease burden in BD I and II. A recent Swedish study by Alina Karanti, M.D., et al. reported higher rates of depressive episodes, illness onset at a younger age, and significantly higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity (anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and ADHD) among patients with BD II compared with those with BD I. In this Swedish sample, (n>8,700) no differences were noted in substance abuse between BD I and BD II. Interestingly, individuals with BD II generally obtained more education and achieved a higher level of independence than those with BD I.

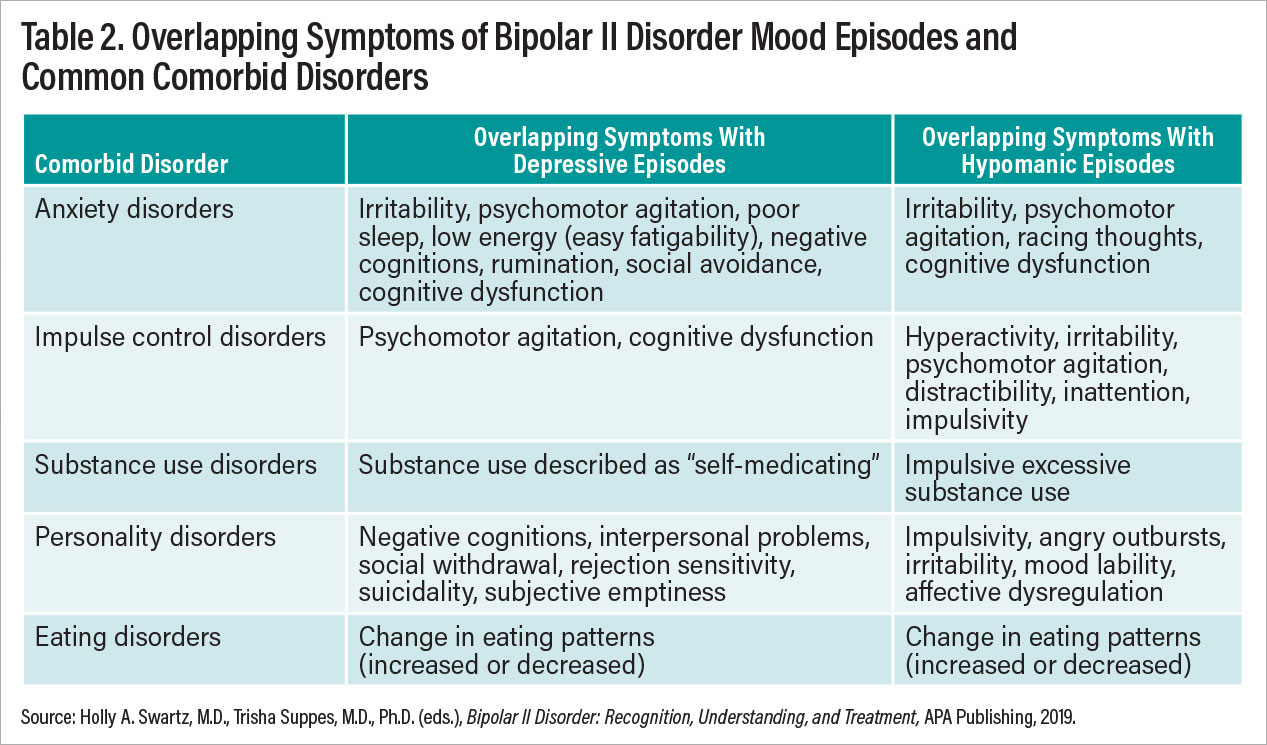

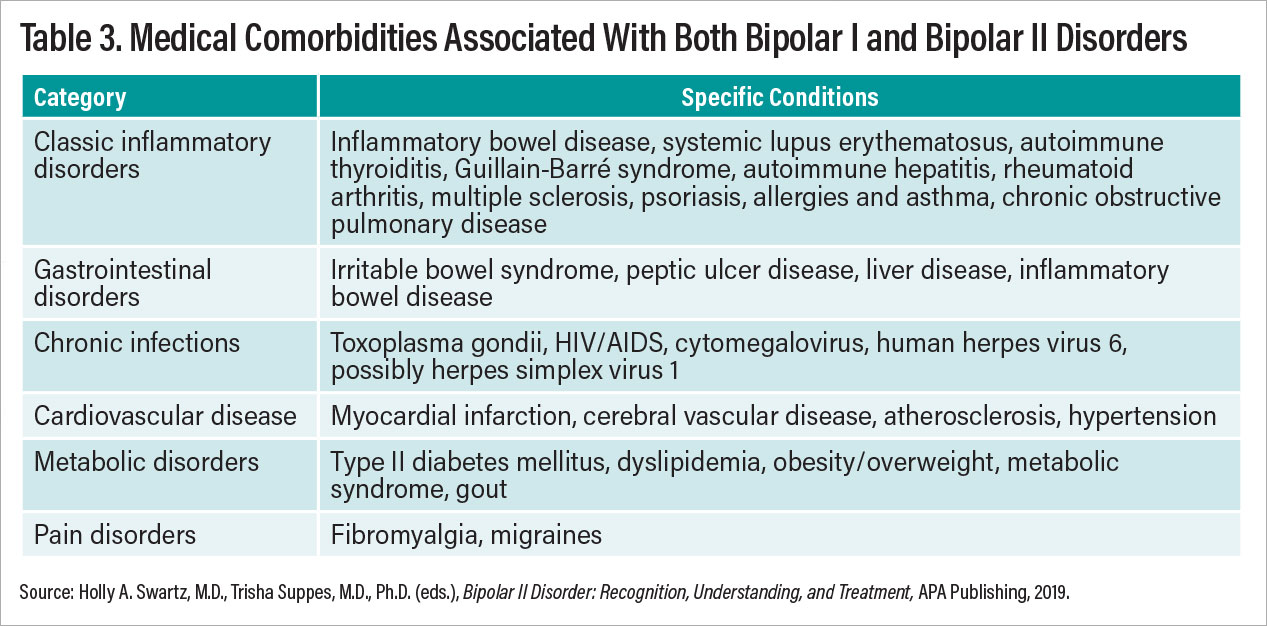

High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with BD II further compound the challenge of differential diagnosis. There is considerable overlap between BD II and anxiety disorders. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder also frequently co-occurs. Approximately 20% of individuals with BD II also meet criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD), and up to 40% of those with BPD are incorrectly diagnosed as having BD I or II. Tables 2 and 3 show estimated co-occurring psychiatric illnesses for patients with BD II. The diagnosis of BD II requires a careful clinical interview of both past and current symptomatology.

Suicide is a significant risk for all patients with BD, and historically patients with BD I were viewed as having a higher risk than BD II due to the extremities of mania. However, data from a number of sources support that suicide risk is high across all patients with BD, and relatively little difference is found in risk for patients with BD I versus BD II. Older studies have suggested this risk may be higher for patients with BD II than BD I, and, indeed, the Swedish bipolar registry database study recently indicated that the rate of suicide attempts was significantly higher in patients with BD II though no data on completed suicides were provided. Overall, the reports from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide found that the risk for suicide was estimated at 164 of 100,000 per year in patients with BD versus 10 of 100,000 per year in the general population (see the reference by Ayal Schaffer, M.D., at the end of this report).

Treatment of BD II

Treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder often give only a passing nod to distinguishing appropriate treatments for BD I versus BD II. The combined guidelines by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) were unusual in making a point of distinguishing the evidence base for BD I versus BD II. They are reported in a 2018 paper by Lakshmi N. Yatham, M.D., et al. (see reference at end of article).

These guidelines have a separate section devoted to BD II, and they clearly state that one cannot directly apply studies on patients with BD I to management of patients with BD II. The conclusion of these guidelines is that there are too few controlled studies in patients with BD II to make detailed evidence-based recommendations or develop evidence-based treatment algorithms. Below is a brief overview of our current knowledge of treatments for patients with BD II with medication and/or psychotherapy.

Antidepressants

It is worth highlighting that, while monotherapy antidepressants would be viewed as an inappropriate practice for patients with BD I depression, studies suggest that the risks and benefits may be different for those with BD I and BD II. In at least one study, risk of switching to hypomania was no greater with lithium than with sertraline monotherapy. Other studies have shown antidepressant monotherapy to be an efficacious monotherapy for BD II. Meta-analyses on risk of antidepressant-induced switches are inconclusive, though the risk of treatment-emergent (hypo)mania due to medication appears to be less in patients with BD II than in patients with BD I depression receiving monotherapy antidepressants. Absent conclusive data on antidepressant switch rates, without a past record of good response to antidepressant monotherapy, current treatment guidelines suggest starting with lithium or a mood stabilizer before adding or switching to antidepressant monotherapy. Additionally, it is important to note that antidepressants in some patients may worsen the overall course of illness and may not be efficacious in some patients with BD II. Any patient who experiences hypomania or mania (which must be distinguished from transient activation symptoms) while on antidepressant medication should be presumed to be on the bipolar spectrum.

Antipsychotics

Most atypical antipsychotics have not been studied for the treatment of both BD I and BD II depression, with two notable exceptions. Quetiapine registration trials included individuals with BD II, with post-hoc analyses demonstrating efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy for BD II depression. Lumateperone is the first antipsychotic formally studied for depression response in patients with BD II since quetiapine trials in the early 2000s. Lumateperone, in randomized, controlled trials, performed as well or better for BD II than BD I, according to a 2021 study by Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D., et al. Cariprazine and lurasidone, while both FDA approved to treat bipolar depression, were never formally studied in patients with BD II. There have been case series supporting their use in BD II depression, but no randomized, controlled trials have been carried out. FDA approval to treat patients with BD II depression with lumateperone came in 2021, 15 years after quetiapine was approved. This glacial rate of accruing new FDA-approved compounds for BD II speaks to the need for more studies in this population.

Lithium and Anticonvulsants

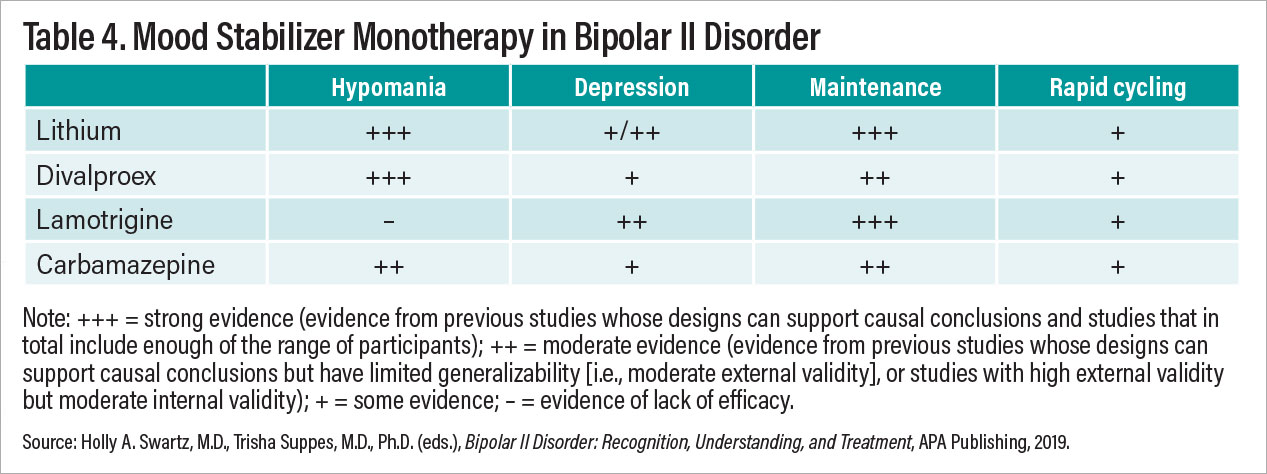

While we might expect lithium to be the frontrunner treatment for managing BD II, study results are varied. Certainly, for hypomania and maintenance treatment of patients with BD II, lithium is a top choice. Lithium has a disappointingly poor track record for treating BD II depression with little indication that response rates are superior to those of antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics. Lamotrigine has good evidence for preventing new depression episodes in the context of BD (both BD II and I). The evidence, however, is less robust for treating acute depression in patients with BD II. In clinical practice, many clinicians prescribe lamotrigine, especially as an adjunctive treatment, for BD II depression, but our ability to make firm recommendations with confidence about lamotrigine is limited.

Other Therapies

Rapid-acting therapies are on the rise across all treatments for depression. There has been a recent surge of clinical work and research examining transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), ketamine, and psychedelics and related compounds. More work is needed specifically focused on BD II depression before firm conclusions may be drawn.

There is limited evidence supporting the use of TMS for BD II depression. This evidence base is developing, and more information is forthcoming on the utility of TMS for BD II depression.

Ketamine and Psychedelic Studies

Racemic ketamine has been in use for many years as an anesthetic and more recently was approved by the FDA as intranasal esketamine (the s-enantiomer of racemic ketamine) as a treatment for MDD. Three small studies of racemic ketamine suggest that it is effective for BD II depression. A 2022 observational study by Farhan Fancy et al. assessing patients with BD I versus BD II treated with racemic ketamine included more than 60 patients (n=35 BD II). In this largest open observational study to date involving ketamine and BD, patients with BD II demonstrated a more robust response than those with BD I. More studies are in development exploring this new use of an old drug; to date, there is no information on the role of esketamine for bipolar depression, let alone BD II.

Recently, it’s been difficult to pick up a journal or look at other media without seeing something about psychedelics and related compounds. There is a surge of interest in psychedelics for MDD, although evidence about their effectiveness is still early and with rare exceptions involves small samples. There is one report on treatment of depression with psilocybin in patients with BD II. In this pilot study, 15 patients with BD II were given a one-time dose of psilocybin (25 mg) and provided preparatory, dosing, and integration therapy consistent with psilocybin studies in MDD. In this small open study by Scott Aaronson, M.D., et al., the rate of response at 3 and 12 weeks was more robust than has been observed in MDD studies. An ongoing study is assessing the durability of patients’ response to psilocybin administered one time for patients with BD II depression. While no notable adverse events or increased mood lability were noted in this small sample to date, further study is needed to assess benefits and harms.

Psychotherapy

Most information about psychotherapy for BD II is derived from trials of interventions for BD in general that also included a subset of individuals with BD II. A recent systematic review of psychotherapies for BD II identified over 1,000 individuals with BD II who participated in randomized, controlled trials testing psychosocial interventions to treat depression or prevent recurrence of mood symptoms. However, relatively few of these trials—only eight of 27—examined outcomes in those with BD II separately. From this review, we concluded that there is preliminary evidence supporting the efficacy of several evidence-based psychotherapies for BD II: cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, family focused therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), and functional remediation. None of these psychotherapies have undergone rigorous testing in randomized, controlled trials focused specifically on BD II depression, with the exception of IPSRT, pointing to the need for additional research in this area. To our knowledge, no meta-analysis of psychotherapy for BD II has been published.

IPSRT, the only psychosocial intervention to be tested in a randomized, controlled trial consisting of participants with BD II only (rather than a mixed patient population of BD I and II), focuses on helping individuals develop more regular routines to stabilize underlying disturbances in circadian rhythms. Because abnormalities in circadian biology have been implicated in the genesis of bipolar disorders, including BD II, a chronobiologic behavioral approach may be especially helpful to mitigate BD II symptoms.

Conclusions

BD II is a relatively common disorder affecting approximately 0.4% of the population. Its prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are comparable to that of BD I. Evidence supports conceptualizing BD II as a distinct phenotype, separable from both BD I and MDD. Compared with BD I and MDD, far less is known about BD II and how to treat it. Further, despite being reliably diagnosed in DSM-5 field trials, BD II is frequently misdiagnosed in practice, resulting in a decade-long lag between onset of symptoms and appropriate diagnosis. A neglected condition, BD II causes unnecessary suffering in those who are misdiagnosed or for whom appropriate treatments are unclear. More research is urgently needed to improve identification and treatments for BD II. ■