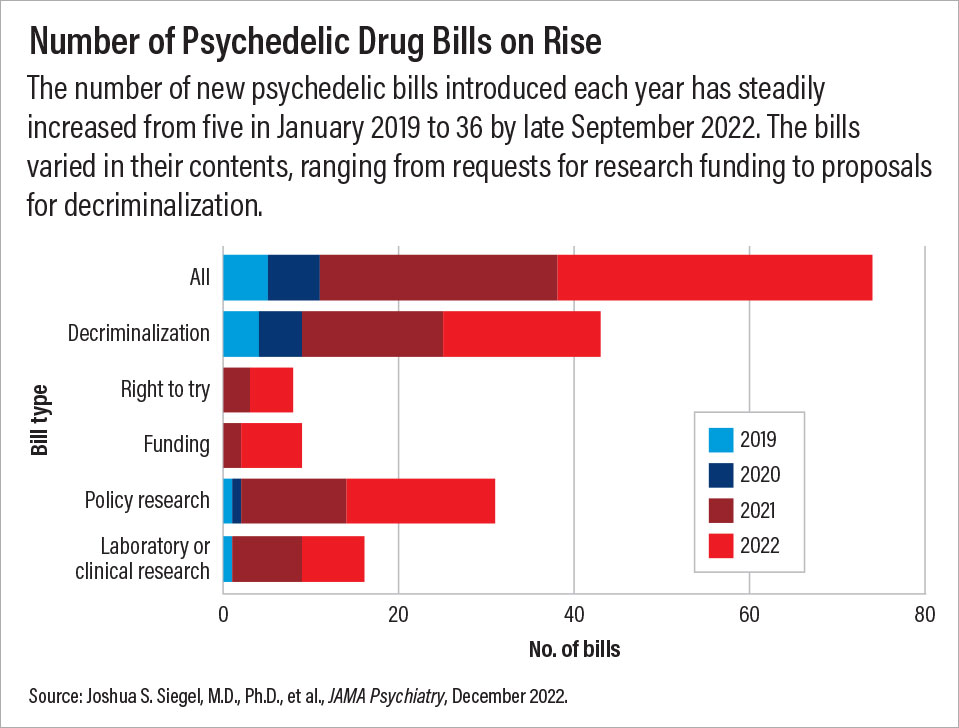

Legislative reform regarding psychedelics is gaining ground, a

study in

JAMA Psychiatry has found. From January 1, 2019, to September 28, 2022, 25 states considered 74 bills that proposed to reform existing laws restricting access to psychedelic drugs or proposed further research into reform legislation, and 10 of those bills had been signed into law by seven states.

The vast majority of the bills—90%—specifically referred to psilocybin, and 36% of the bills also included 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA). Less than 20% of the bills included peyote/mescaline, ibogaine, LSD, and/or DMT/ayahuasca.

Among all bills, 58% proposed decriminalization and 42% proposed policy research to explore paths to decriminalization. The focus of those that proposed decriminalization varied widely, as follows:

•

51% called for legalization of possession of at least one psychedelic drug for therapeutic or recreational purposes.

•

35% indicated that some training or licensure would be provided to prescribe psychedelics or to provide psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

•

23% mandated that access to psychedelics be restricted to some medical environment, such as a registered treatment center.

•

12% explicitly mandated physician involvement in prescribing psychedelics or making qualifying diagnoses.

“As the analysis results came in, I don’t think any of us were expecting the sheer heterogeneity of bills being considered, and that a majority of decriminalization bills did not call for medical oversight or licensure,” said lead author Joshua S. Siegel, M.D., Ph.D., a neuroscientist and psychiatrist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “I think there needs to be a public conversation—not necessarily led by the Food and Drug Administration, Drug Enforcement Administration, or the corporations looking to get rich from psychedelics—about how we want to incorporate these drugs into American society.”

Jonathan E. Alpert, M.D., Ph.D., chair of APA’s Council on Research, expressed concern that such a small proportion of bills would require training or licensure for psychedelic prescribing and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy or mandate physician involvement.

“We don’t have a lot of knowledge about the risks and safety of psychedelics use, any drug interactions they may have, or their long-term effects, particularly in those who might be vulnerable to their effects by virtue of having a family history or prior symptoms of psychotic disorders,” said Alpert, who was not involved with the study. He is the Dorothy and Marty Silverman University Chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Montefiore Medical Center and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

“From the perspective of state legislatures and the ballot box, the idea of decriminalization is one thing. It is within the purview of states to make those decisions. But there is already an appropriate framework in place for decisions about the therapeutic use of psychedelics or other substances,” Alpert added, referring to the FDA’s pathway for approval. “If we really care about their potential for therapeutic benefit, short-circuiting the process doesn’t serve that goal.”

Alpert’s sentiments echo those of an

APA position statement he coauthored on the use of psychedelic and empathogenic agents for mental health conditions. The position statement, released last year, is explicit about the Association’s stance: “There is currently inadequate scientific evidence for endorsing the use of psychedelics to treat any psychiatric disorder except within the context of approved investigational studies. APA supports continued research and therapeutic discovery into psychedelic agents with the same scientific integrity and regulatory standards applied to other promising therapies in medicine. Clinical treatments should be determined by scientific evidence in accordance with applicable regulatory standards and not by ballot initiatives or popular opinion.”

The authors of the JAMA Psychiatry study wrote that although the proposed laws differ considerably, all of them, directly or indirectly, contradicted or sidestepped the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970.

“Some of the proposed bills that we studied are narrow enough that they do not directly contradict the federal Controlled Substances Act. For example, some of the bills only go as far as calling for a policy study and would not directly legalize or decriminalize these drugs,” study researcher James E. Daily, J.D., M.S., told Psychiatric News. He is a researcher, lecturer, and data scientist at the Center for Empirical Research in the Law at Washington University in St. Louis. “But those bills tend to at least contemplate future decriminalization or legalization. It is safe to say that a substantial majority of these proposed state laws either directly contradict the CSA or are at least not in alignment with current federal drug policy.”

Alpert noted that legislative reform regarding cannabis followed a similar pattern.

“Things unfolded fairly quickly, and it caused a lot of confusion with respect to the differences between decriminalization, legalization for medical use, legalization for recreational use, [FDA] approval for treating recognized medical conditions, and Drug Enforcement Administration scheduling.”

To that end, psychiatrists should be prepared to answer their patients’ questions about psychedelics, said Alpert.

“It’s critical for psychiatrists to talk with patients about the current status of psychedelic drugs as promising therapies that at this time are almost exclusively investigational and need to be subjected to the same rigorous study and regulatory approvals as other drug therapies,” Alpert said.

As Psychiatric News went to press, at least five states had introduced new bills regarding psychedelics since January 1.

This study was supported by the Taylor Family Institute Fund for Innovative Psychiatric Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. ■