People with depression who have been successfully treated with antidepressants

exhibit distinct changes in the brain relative to those successfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), according to a report in

The American Journal of Psychiatry.

“Despite the theorized differences in how antidepressants and CBT exert their effects, no controlled study has explored the impact on the brain of these two very different types of treatment,” said Boadie Dunlop, M.D., the lead author of the report. “There is a lot of interest in using brain imaging to identify differences between people with or without depression, but it is also important to understand what happens to the brain when it gets better.” Dunlop is an associate professor of psychiatry and director of the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program at Emory University School of Medicine.

Dunlop and colleagues used data collected as part of the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) trial. For this trial, 344 adults aged 18 to 65 with major depressive disorder who had never been treated for the disorder were randomized to receive 12 weeks of escitalopram, duloxetine, or CBT. The subjects underwent a functional MRI (fMRI) scan before and after the 12-week study.

Using the PReDICT data, Dunlop and colleagues in 2017 reported that they had

identified baseline brain connectivity patterns that could reliably predict whether patients would respond to CBT or antidepressants. For the current study, the researchers examined data from 131 PReDICT participants who completed the 12-week trial and had two fMRI scans (one at baseline, one after 12 weeks) to identify changes in connectivity.

In total, 49.5% of the participants who took medication and 47.5% who received CBT achieved remission—defined as a score of 7 or less on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating (HAM-D) Scale.

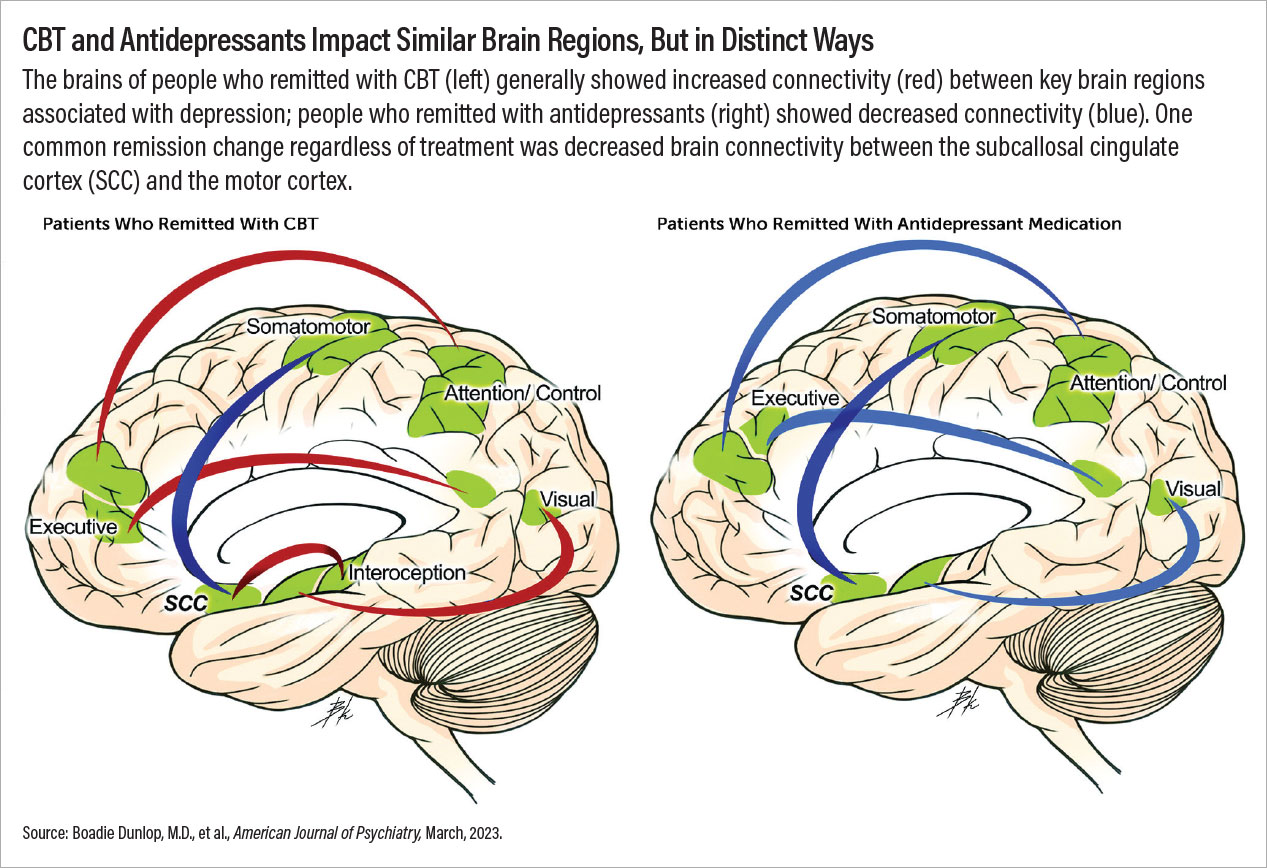

The researchers observed a stark difference in the scans of the participants after they received 12 weeks of treatment. In general, people who achieved remission following use of antidepressants showed reduced connectivity (electrical activity) between certain brain regions compared with baseline. In contrast, people who achieved remission following CBT had increased connectivity between these same regions.

These changes in brain connectivity did not occur in people who did not achieve remission, regardless of treatment. This suggests the changes are not simply due to receiving medication or therapy, but the individual’s response to it, Dunlop said.

Notably, remission following CBT was associated with stronger connections between the brain regions that control executive function—the cognitive ability to process and prioritize information to complete a task—and attention. Executive function is often impaired in patients who are depressed, which can result in negative attitudes and beliefs being prioritized by the brain before positive ones, Dunlop explained. Cognitive training helps people to identify maladaptive thoughts and push these thoughts away.

“To my knowledge, this is the first biological demonstration that the core target of CBT is activated in people who respond to therapy, and this activation is specific to CBT,” Dunlop said. He added that people who showed greater connectivity increases in the executive function network after 12 weeks also had greater improvements in HAM-D scores, supporting that this network is engaged during CBT.

Depression-Movement Connection

While the participants’ brain scans primarily showed that medications and CBT generally had opposite effects on connectivity, they had one change in common: People who achieved remission with either CBT or antidepressants showed reduced brain connectivity between the subcallosal cingulate cortex (a central hub for processing emotions) and the motor cortex (which controls movement).

“When people are no longer depressed, they frequently report it is easier to initiate motor actions, such as getting out of bed or moving more quickly from one place to another,” Dunlop said. It’s possible that in depressed people, the extra burden of negative emotions processed by the subcallosal cingulate cortex may cause increased inhibition of the motor cortex, he continued. As depressive symptoms lessen, motor activity increases.

“This is all speculation, though, since our data cannot tell us the direction of the information exchange,” Dunlop cautioned.

Dunlop believes these findings provide neurological evidence to support the clinical practice of switching or combining treatment modalities if someone doesn’t respond to a first-line treatment. Since CBT and antidepressants are associated with distinct brain connectivity changes, a patient who doesn’t respond to one may be more likely to respond to the other.

Dunlop’s team is now analyzing two-year follow-up data collected from the PReDICT participants to determine if there are clues in the fRMI images regarding patients who are most likely to experience depression relapse.

“We need to improve the long-term management of this disorder,” he said. “Right now, it’s typical to keep people on maintenance antidepressant therapy, but not everyone needs that. If we can better predict who can stop treatment or should continue, that would meet an enormous public health need.”

The PReDICT study and subsequent analyses were supported by multiple grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and National Center for Research Resources. Forest Laboratories and Eli Lilly donated the escitalopram and duloxetine, respectively, used in the trial. ■