Vaping is a generic term that usually refers to the use of electronic nicotine delivery devices. Generally these devices consist of a battery to power the unit, a cartridge with e-liquid (also known as e-juice), and an atomizer to heat the e-liquid. Heating the e-liquid produces an aerosol that is inhaled through a mouthpiece. Vaping devices were commercially introduced in 2007 and have evolved through several generations of products as follows:

E-juice generally contains nicotine, flavors, a humectant such as glycerin or propylene glycol to preserve moisture when heated, and other chemicals such as cannabis concentrates. Many of these chemicals are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for consumption.

A pack of traditional cigarettes usually has about 20 cigarettes that contain a total of 20 mg of nicotine. JUUL pod solutions have about 41 mg of nicotine, and Suorin pods contain about 90 mg of nicotine. According to the nonprofit Truth Initiative, concentrations of nicotine

can be as high as 4% in these products in the United States, whereas in Europe the limit is 2%. Even products listed as “nicotine free” may contain nicotine due to mislabeling and lack of regulation.

Prevalence of Use

Vaping is on the rise in the United States. According to

a June report in

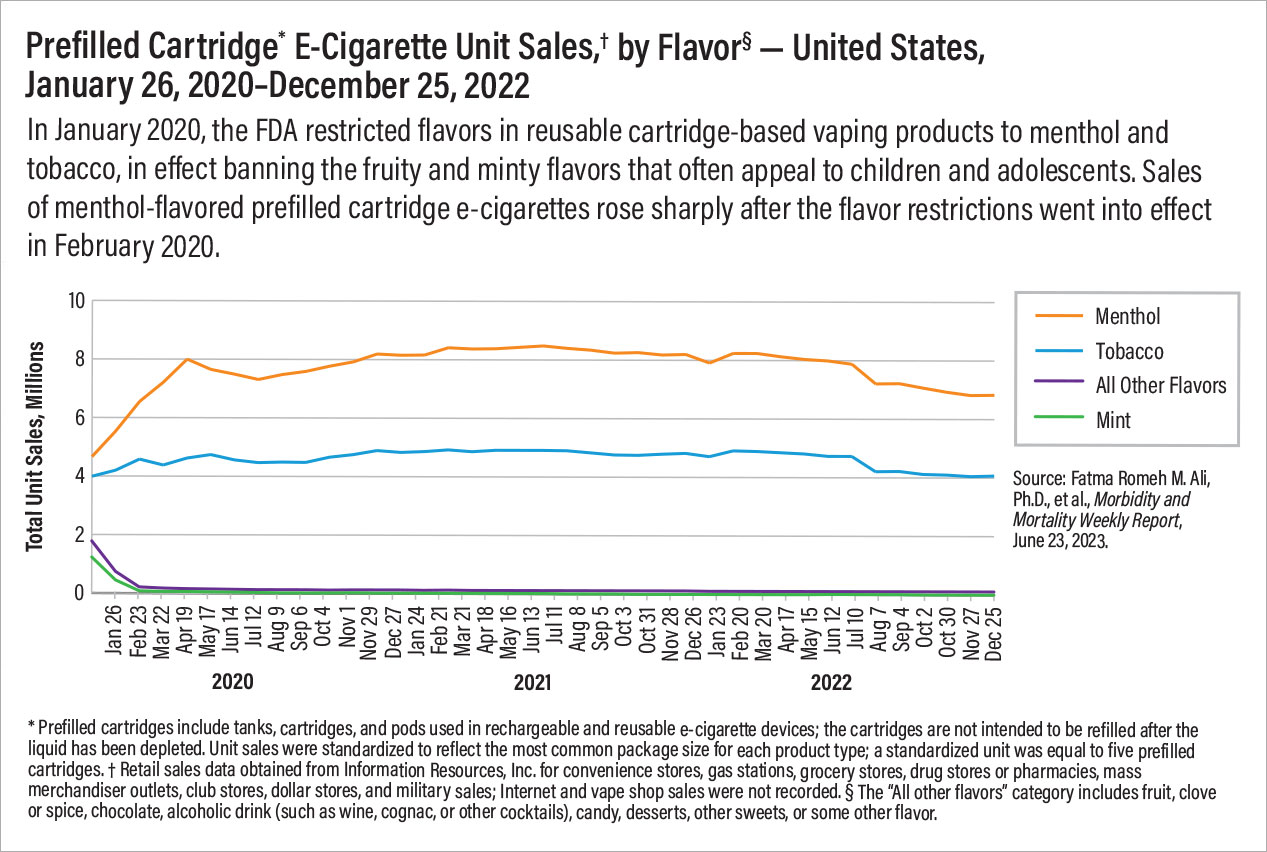

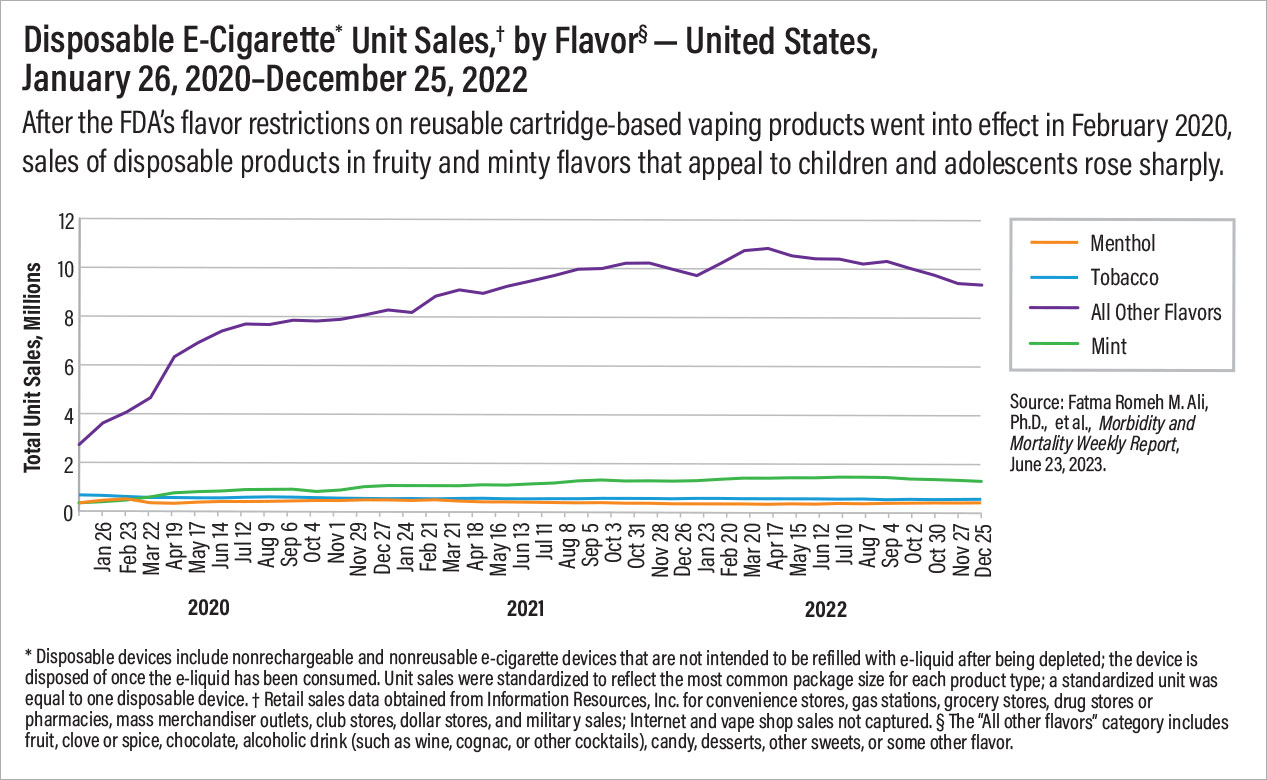

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), unit sales of vaping devices increased 46.6% between January 2020 and December 2022. The prevalence of e-cigarette use is markedly higher among youth and young adults than it is among adults overall. In 2021, 4.5% of all adults aged 18 years or older and 11% of young adults aged 18 to 24 years reported vaping at least once a day during the previous 30 days.

A report appearing in

MMWR in October 2022 found that in 2022, 14.1% of high school students and 3.3% of middle school students reported vaping in the previous 30 days. Among these, 30.1% of high school students and 11.7% of middle school students reported vaping every day.

Cannabis vaping is also increasing among both adults and adolescents.

A study in the December 2021 issue of

Preventive Medicine drew data from more than 160,000 adults in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and found that the prevalence of past 30-day cannabis vaping increased from 1.0% in 2017 to 2.0% in 2019. Over the same period, the prevalence of past 30-day cannabis vaping increased from 1.2% to 3.9% among adults aged 18 to 24 years. A separate

study in

Addiction in May 2022 examined data from 51,000 adolescents and revealed that although past 30-day frequent and occasional cannabis use (six or more instances and one to five instances, respectively) without vaping declined from 2017 to 2019, frequent or occasional use that included any vaping increased over the same time frame. The largest increase occurred among those who reported frequent cannabis use including vaping, from 2.1% in 2017 to 5.4% in 2019.

The FDA may regulate vaping products under the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, but such regulation has been limited at least in part by the burden of review.

As of May 2022, the FDA had received nearly 1 million applications for vaping and other nontobacco nicotine products from more than 200 separate companies. Thus far the FDA has authorized approximately 23 tobacco-flavored vaping products and devices, although many more products are in circulation.

In January 2020, the FDA restricted flavors in cartridge-based reusable vaping products to just menthol and tobacco, in effect banning the fruity and minty flavors that often appeal to children and adolescents. However, the flavor restriction did not apply to disposable vaping products. As a result, sales of flavored disposable vaping products increased after the ban. Furthermore,

information published by the Associated Press in June revealed that the number of different electronic cigarette devices sold in the United States has nearly tripled since 2020. This increase is largely driven by sales of unauthorized disposable vaping products from China, most of which come in sweet and fruity flavors that appeal to children and adolescents.

Risks of Use

It is hypothesized that there is less harm from vaping than from smoking traditional cigarettes. However, studies have shown that vaping products contain carcinogens similar to those found in traditional cigarettes.

Vaping products also carry unique threats to health. Glycerin in e-juice may cause lipoid pneumonia on inhalation, and propylene glycol in e-juice may cause respiratory irritation and increase the risk of asthma. Flavors like cinnamaldehyde or diacetyl may cause pulmonary injury.

Examples of harmful chemicals in aerosolized vapor include nicotine; ultrafine particles that can be inhaled deep into the lungs; volatile organic compounds; and heavy metals such as nickel, chromium, tin, and lead. Vaping has recently been linked to asthma, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and emphysema. Other

recent research reports associations between aerosols, blood vessel function, and cardiovascular risk. In addition to all of the short-term risks, there is still a lot unknown about long-term effects of these relatively new products.

Of particular concern is e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI), a condition characterized by cough, labored breathing, reduced blood oxygen levels, and elevated white blood cell counts. As of February 2020, EVALI had resulted in more than 2,800 hospitalizations, including

68 deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Among these cases, 82% of patients reported vaping delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The presence of vitamin E acetate in e-juice is associated with an increased risk of EVALI, and vitamin E acetate is used as an additive in some THC-containing vaping products. As a result, the CDC recommended that people not use vaping products that contain THC, especially those acquired from informal sources such as friends or family members, or from in-person or online dealers. However, the CDC has not conclusively determined vitamin E acetate to be responsible for EVALI.

Young people who vape may be at risk of developing other substance use disorders. Because brain development continues up to roughly age 25, the young brain is susceptible to long-term effects of nicotine.

Although vaping does not emit secondhand smoke, it emits secondhand aerosols. These aerosols are known to include nicotine, heavy metals, carcinogens, and volatile organic compounds. More needs to be understood about the impact of that exposure.

Of increasing concern is the practice of vaping cannabis oil or THC concentrates. THC is the main psychoactive compound in cannabis, responsible not only for addiction, but also neuropsychiatric adverse effects. Vaping devices offer potential for greater THC absorption as a more efficient delivery system and can also enable a user to consume highly concentrated THC products when compared with being smoked in a combustible way (joints). The short-term risks of cannabis and THC concentrates include altered perception; impaired coordination; difficulty with thinking/memory; and, when used in high doses, psychotic symptoms. Long-term effects include impairments in thinking and learning and risks related to the onset of psychotic disorders. These effects are more likely to occur in adolescents and young adults, particularly if they use a high-potency formulation when they initiate cannabis use.

Implications for Practice

As psychiatrists, we will most likely see a disproportionate number of patients who vape, similar to how we see a disproportionate number of patients who smoke. According to

a study in the July 2020 issue of

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, people with mental illness are more likely to use e-cigarettes and to use them more frequently than people without mental mental illness. A

scoping review published online in the

Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives in May 2022 found that e-cigarette use versus nonuse has been associated with depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Furthermore,

data published in the

Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in February 2021 suggest that vaping nicotine is associated with mental health changes similar to those associated with smoking traditional tobacco cigarettes.

Screening for use of all tobacco products and other substances is a first step. Integrating these into our patients’ medical histories will help inform our care and make discussion of these products with our patients routine. In screening for vaping, one can more broadly start by inquiring about nicotine and cannabis, two of the most commonly vaped substances, and then ask about specific products—for example, specifying vaping and vaping products in addition to smoking cigarettes. After inquiring about use, consider the impacts of the use as highlighted by the DSM-5 criteria. For example, a patient may come to you for depression and screen positive for vaping. Asking the patient questions based on DSM-5 criteria, such as “Have you used more than intended? Have you tried to quit or cut down unsuccessfully? Has it impacted your health?” may help patients consider that they may have a substance use disorder.

Next, adopting the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

guidelines for tobacco treatment, giving advice to quit, and inquiring about patients’ interest in changing use patterns will help enhance their motivation, if not immediately during the visit, then in the future.

When patients are interested in quitting, the next steps are reviewing their triggers for use; teaching them how to track their use; developing a quit plan with them; and offering treatments for nicotine use disorder such as nicotine replacement, bupropion, or varenicline. The final step is determining a follow-up plan, either with you, a quit line such as 1-800-QUIT-NOW, or

smokefree.gov. This will reinforce patients’ progress and help you remember to check in with them in the future. ■