In their letter regarding our recent PRCP study (

1), Spielmans et al. demonstrate a lack of familiarity with rigorous quasi‐experimental research designs. Such designs, however, are essential in studies of health policies, which can seldom or ever be randomized, for example, one can't issue national drug safety warnings to a random sample of the population. Before responding to their specific conclusions, we would like to refer readers to an informative table of the hierarchy of strong and weak research designs.

Table 1 is based on 100s of years of science (

2). It shows a hierarchy of strong research designs that often yield valid results, in contrast to weak designs without baselines (cited by Spielmans et al.) that are largely untrustworthy (i.e., post‐only designs without baselines cannot control for common biases, such as history bias and secular trends) (

3).

Further guidance on research design hierarchy is available (

4,

5,

6).

Spielmans et al. critique our strong interrupted time‐series (ITS) with comparison series study (multi‐age groups used as comparisons) by citing uncontrolled post‐only designs—which are at the bottom of the hierarchy of research designs—alleging that our study proved no effects of black box warnings on antidepressant use. Without a baseline it is impossible to estimate the counterfactual pre‐intervention trend (what would have happened in the policy's absence). The simple truth is that it is misleading to attempt to measure a change occurring after a policy is enacted in the absence of any baseline (pre‐intervention) measure.

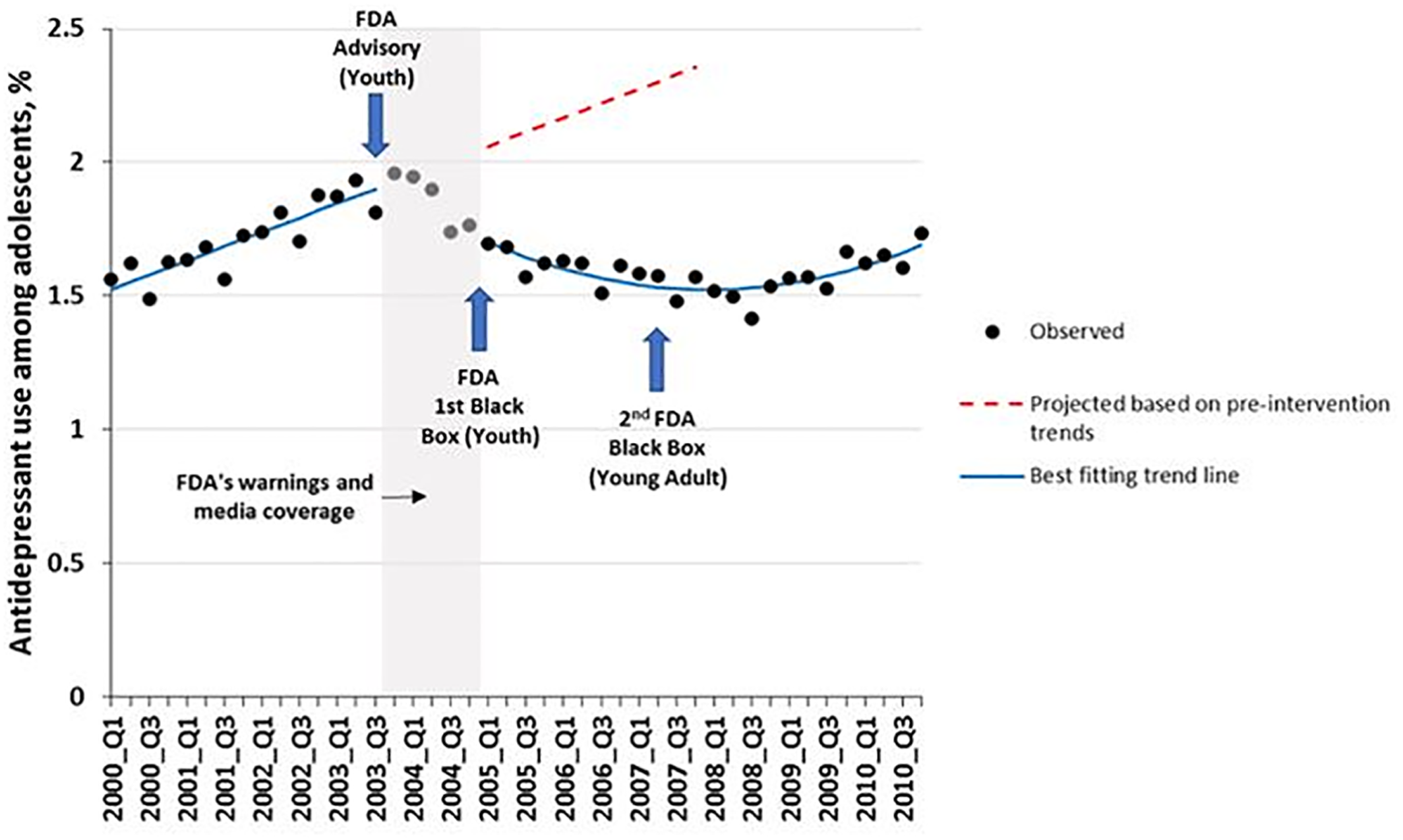

Spielmans et al. conclude that treatment of youth depression has not declined substantially since the warnings, and they defend this statement by a misleading and selective observation that “Lu et al (our previous study) found a decrease in …treatment of less than one percentage point.” This conclusion is false when one simply observes the sudden and sustained change in trend of antidepressant use after a substantial increase in trend during the 14 quarterly baseline observations before the advisory (

Figure 1).

What is immediately apparent in Figure 1 is that the “less than one percentage point” reduction in treatment was from less than a 2 percent prevalence of treatment just

before the warnings. (The denominator was all adolescents and the relative reduction was greater than 30 percent. Thus, by ignoring the relative reduction, Spielmans et al. understate the effect by more than 30 times.) The difference (effect) between the counterfactual baseline trend and the actual observation at the time of the second black box warning is almost 50% of all adolescents per quarter (approximately 1.1 million adolescents in the 11 US health systems). Failing to provide both absolute and relative changes in effect estimates is a major bias in both media and scientific reporting of the effects of health technologies and policies. Such failings distort findings in ways that adversely affects both science and health policies, sometimes with patient harms (

7,

8).

The sudden reduction in the above ITS and comparison series study is evident to a non‐scientist—the tremendous decrease in both level and slope, controlling for the rising baseline trend probably persisted for about 7 years following the initial advisory warning in the fall of 2003. But we conservatively estimated medication use and suicidality effects only for several years beyond the warnings because the confidence intervals of ITS effects gradually become wider over time.

The other studies cited by Spielmans et al. to refute our results (that the warnings reduced treatment) are weak post‐only designs (

Table 1) with uninterpretable findings that violate the basic research design criteria of the worldwide Cochrane Collaboration's systematic reviews (

9,

10,

11). Post‐only studies are excluded altogether from any rigorous Cochrane reviews (

12). Studies with insufficient baseline trends (pre‐post designs) also offer weak, if any, evidence of causal inference. For example, the Valluri study has only three monthly data points before the first advisory (Oct. 2003) and none from prior years. The data showing the well‐known, steep rise in antidepressant use before the first advisory (see baseline in

Figure 1) are missing in the Valluri paper; absent these critical observations of baseline trends, their data are insufficient. Moreover, their paper lacks any data occurring during the second black box warning in 2007, as well as any other year after the warning. Effect estimates (change from before to after) are impossible without reliable measures of the pre‐ and post‐policy trends. Similarly, Kafali et al cannot reliably measure pre‐advisory counterfactual trends with only three points. Baseline trends can be rising, stable or falling; without adequate baseline data, attempts to measure before‐to‐after changes are biased, and all too frequently misleading and deceptive.

Speilmans et al. then cite post‐only correlations between antidepressant use and suicide attempts only after the warnings began, representing ecological fallacies without any baseline. This claim is based on Ploderl's study using self‐reported antidepressant use and self‐reported suicide attempts. Correlations based on self‐reported measures are often severely compromised by recall and social desirability biases.

In their previously published narrative review, Speilmans et al. (

13) incorrectly depict our prior ITS study as an ecological study examining the relationship between antidepressants and suicide attempts. Narrative reviews are inadequate for informing policy‐making because they do not assess the methodological quality of studies in the field before summarizing credible results. Our ITS studies and other studies that we cited (

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21) employed rigorous quasi‐experimental research methods to examine the effects of FDA warnings on antidepressant use, non‐drug treatments, suicide attempts, and suicides. As shown in

Table 1 and in major research design texts and the Cochrane Collaboration, research on drug safety policies require strong quasi‐experimental designs (preferably ITS with comparison series to assess interruptions in trends, controlling for pre‐policy levels and slopes). The ITS designs can control for many biases, such as history, maturation, and selection (

4). Our study measured the multifactorial effects of risk communications. We did not, as stated by Spielmans, study “whether a drug causes suicidality.” Nor did we measure the adverse effects of policy‐induced reductions in medications alone. Most of the effects were related to demonstrated reductions in both drug and non‐drug depression treatment rates following the warnings (

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21).

The majority of longitudinal ITS studies have demonstrated, in different large samples (including national), that the youth antidepressant warnings have almost simultaneous, unintended effects on identification of depression, psychotherapy, antidepressant treatment, suicidal behavior, and suicide deaths (

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21). They cause sudden shifts in the level and slopes of the trends. A public health policy analysis cannot ignore this number of simultaneous unintended outcomes in different datasets. The burden of proof of policy harms should be on the policymakers creating those policies, not on the outside scientists who have no or fewer conflicts of interest (

22).

Together, findings from these ITS studies (including our own) suggest the boxed warnings may have contributed to the very thing FDA was trying to prevent: youth suicidal behavior and suicides. Even before COVID, more than two thirds of depressed teens did not receive any depression care (

23), an issue now further exacerbated by both the pandemic and the continuing barrage of alarming suicidality warnings contained in all drug labels and TV advertisements. It is time for the FDA to err on the side of caution and reduce the severity of the continuing antidepressant warnings.