Many individuals who identify as sexual minorities experience conflict with religion and religious organizations (

1,

2). However, research on the experiences of sexual minorities elucidates more complicated themes, highlighting limitations in assuming that sexual minority status and religious affiliation uniformly oppose each other (

3,

4). These issues are particularly relevant when it comes to how identities are discussed and explored in a therapeutic setting. Consistent with minority‐stress theory (

5), sexual minorities tend to experience more stigma in daily life (

6,

7), which can lead to startlingly worse mental health outcomes, such as increased rates of depression, anxiety, substance use disorders and suicide attempts (

8). The discrepancies between mental health outcomes of heterosexual and sexual minority individuals underscores the importance of ensuring treatments are available and appropriate for this vulnerable population (

6). To these ends, psychotherapy practitioners may hesitate to address spiritual and religious issues with sexual minority patients—especially in acute psychiatric settings—out of fear that such themes have high propensity to exacerbate their emotional distress. However, more than half of psychiatric patients wish to discuss spiritual/religious topics in treatment (

9). A simplistic approach to spirituality with sexual minority patients may thus be detrimental.

Although some religious institutions have historically and continue to be perpetrators of discrimination against sexual minority groups (

10), it is now also recognized that the role of religion for sexual minority individuals is more complex. The extant literature on religion and sexual minority health is decidedly mixed, in that certain aspects of religion are linked to negative clinical outcomes, but other factors can offset these effects or even improve mental health. In one study, leaving religion due to familial conflict and anti‐homosexual parenting due to religion were associated with increased likelihood of a suicide attempt, and these effects were mediated by internalized homophobia (

11). Such findings suggest that religious conflicts at the family level regarding homosexuality are a risk factor for negative internalized schemas and psychopathology. However, other research has identified that religious affiliation and a sense of belonging to a religious community are associated with fewer suicide attempts among sexual minorities overall (

12,

13). Along these same lines, greater attendance of religious services differentially predicts symptoms of generalized anxiety for sexual minorities depending on one's community; associations are positive within communities that are rejecting or punitive towards homosexuality, and null or negative within communities that are accepting (even partially) of homosexuality (

2). Other research suggests that religious affiliation can serve as a protective factor against the negative impact of stigma and discrimination, among sexual minorities. One study found that positive religious coping—the adaptive/healthy utilization of religion to cope with distress—was not only commonly used in the context of sexual stigma, but related to numerous positive outcomes (

14). Similarly, Gattis and colleagues (

15) found that affiliation with religious communities that affirm same‐sex marriage protect against perceived discrimination, as well as depressive symptoms. Summarizing and synthesizing all of these trends, a recent meta‐analysis by Lefevor and colleagues (

16) noted that despite the heterogeneity of existing research in this area, sexual minorities generally find religion and spirituality to be beneficial as long as they

elect to engage with it, but find it harmful when it is coerced or forced upon them.

Given the complex relationships between sexual minority status, religion, and mental health, it is important to consider the implications of integrating spirituality into psychotherapy, particularly when delivering care to acute psychiatric patients. Recently, we developed and described an innovative treatment program dubbed Spiritual Psychotherapy for Inpatient, Residential & Intensive Treatment (SPIRIT), a CBT‐based psychotherapeutic approach which allows for delivery of spiritual psychotherapy to demographically, clinically, and religiously diverse acute patients in psychiatric hospital settings (

17). We subsequently evaluated patient responses to SPIRIT within a large‐scale feasibility trial, and perceived benefit was generally positive and not moderated by patients' demographic or clinical factors (

18). It should be noted that many variants of spiritually‐integrated psychotherapy—which utilizes spirituality and religion in the context of mental health interventions—have been developed in recent years (

19) to treat depression (

20), anxiety (

21,

22), substance misuse (

23), and many other presenting problems (see Smith and colleagues (

24) for a meta‐analysis and review). Some have suggested that such approaches are not appropriate for sexual minorities out of concern that they could engender or increase spiritual and emotional struggles (

25). However, we are not aware of any research on the intersection of sexual minority status and spiritually‐integrated treatments.

The overall objective of the current study was to compare the experiences of sexual minority and heterosexual adult psychiatric patients who self‐referred to participate in SPIRIT. Specifically, we sought to elucidate whether sexual minority patients differ from heterosexual patients with regard to (1) clinical and demographic profiles prior to treatment, (2) spiritual and religious characteristics, (3) spiritual distress, and (4) perceived benefit from spiritual cognitive behavioral therapy. We hypothesized that sexual minority patients would report greater clinical severity, less spiritual/religious engagement, and greater spiritual distress overall. Given the paucity of research in this area, we did not propose any specific hypotheses regarding responses of sexual minorities compared to heterosexual patients to SPIRIT.

METHODS

Procedures and Participants

This study was conducted within the McLean Hospital Behavioral Health Partial Hospitalization Program, a step‐down program from acute inpatient care, offering acute treatment for individuals with severe anxiety and affective disorders as well pervasive emotion dysregulation and interpersonal dysfunction. Over a period of 1–2 weeks, patients attended five, 50‐min group sessions per day, one of which was the SPIRIT group. As described elsewhere (

17), SPIRIT is a stand‐alone, single‐session group psychotherapy that is comprised of structured elements while allowing for flexible delivery. Its primary goals are three‐fold: (1) to help patients clarify how spirituality/religion may be related to their symptoms in positive and negative ways; (2) to identify ways to help patients identify ways to draw upon spirituality/religion as a resource in their treatment, and (3) to identify and validate spiritual/religious struggles that may exacerbate distress. McLean Hospital clinicians were trained prior to providing SPIRIT by study staff. Clinicians received guidance and materials including a clinical protocol and handouts, but they were also able to utilize various aspects of the protocol in each given session, depending on the demographic, spiritual/religious, and clinical characteristics of the group.

Study participants included 81 adults (age: M = 36.5, SD = 15.6; 95% Caucasian and 56.8% female) who voluntarily chose to participate in SPIRIT between March 2018 and April 2019. Sexual minority status was determined based on participant self‐report, as available in clinical files. Of the 81 patients, 15 identified as Lesbian/Gay, Bisexual, or “Other” (no participants identified as gender queer/non‐binary or transgender). Subsequently, participants were stratified into sexual minority or heterosexual groups for the purposes of analysis only. Demographic information regarding participants age, gender, race, employment status, as well as clinical information such as psychiatric diagnoses, medications, suicidality, self‐injurious behavior, electroconvulsive therapy procedures, and hospitalization in the past six months, were obtained from medical records. Participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. The study protocol was approved by the Massachusetts General Brigham Institutional Review Board.

Measures

General spirituality/religion

Participants responded to the following questions about general spirituality/religion: (1) Is religion important in your life? (2) Is spirituality important in your life? (3) Do you believe in God/Higher Power? (4) Are you active in a faith community/congregation? (5) Does your spirituality/religion help you to cope? Items were rated using a five‐point Likert‐type scale with scores ranging 0–4 (“Not at all” to “Very much”). In some instances, analyses included these individual items separately, but in order to provide an omnibus assessment of general spirituality/religion, responses to items were also summed to create a composite score of general spirituality/religion ranging from 0 to 20 (M = 12.56, SD = 5.34). This measure had high internal validity, with Cronbach's α = 0.84 demonstrated in this study sample. Participants also were asked about affiliation with a particular religious group, and subsequently, patients were stratified as either affiliated or unaffiliated.

Spiritual distress

Spiritual distress was assessed using a four‐item subscale from the Clinically Adaptive Multidimensional Outcome Survey (

26), scored using a 5‐point Likert‐type scale ranging from 0 to 4 (“Not at All” to “Very Much”) and summed to yield a single score ranging from 0 to 16 (

M = 4.84, SD = 4.639). Sample items include “I felt concerned about my religious or spiritual life,” and “I felt guilt and regrets over mistakes that were inconsistent with my religious beliefs.” This measure had high internal validity, with Cronbach's

α = 0.84 demonstrated in this study sample.

Perceived benefit from SPIRIT

Patients responded to three items related to their experience in the SPIRIT group: (1) This group clarified how spirituality/religion can be integrated into treatment, (2) This group helped identify spiritual/religious resources that I can utilize to reduce my distress, and (3) This group helped identify spiritual/religious struggles that are contributing to my distress. Items were rated on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale ranging from 0 to 4 (“Not at All” to “Very Much”) and summed to create a composite score ranging 0–12 (M = 7.50, SD = 3.18). These items had acceptable internal validity, with Cronbach's α = 0.74 demonstrated in this study sample.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0 (SPSS). Chi square analyses were used for comparisons of race/ethnicity and religious affiliation, and clinical variables (psychiatric diagnoses, self‐injury and suicide information).

T‐tests were used to compare general religiosity (total score and individual items), spiritual distress and perceived benefit of SPIRIT (total score and individual items) between sexual minority and heterosexual groups. Exploratory correlation analyses were conducted to evaluate whether general spirituality/religion or spiritual distress was differentially related to treatment outcomes among sexual minority versus heterosexual participants. There was a very limited amount of missing data: one participant was missing one item for general spirituality/religion, five patients were missing one spiritual distress items, and six patients were missing one perceived benefit of SPIRIT item. All missing data were from the heterosexual group. Imputed mean values were calculated for these missing values in order to utilize all available participants in our analyses. Additionally, we conducted a post‐hoc analysis of statistical power (

27). Given that mental health discrepancies between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals are well documented and sizable, we anticipated that any observed differences between these groups would be large; power was thus calculated to be 0.87 within our sample.

RESULTS

In the entire sample, primary clinical diagnoses included substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar spectrum disorders, trauma and stressor‐related disorders, obsessive‐compulsive related disorders, dissociative disorders, and psychotic disorders. Approximately one third of patients (30.9%) had been previously hospitalized in the last six months, and 20 patients reported suicidal ideation at admission.

Across groups, most patients reported religious affiliation (53, 65.4%); 12 patients reported no religious affiliation, 16 patients reported being spiritual without religious affiliation, and the most common affiliations were Catholic (17.3%) and Protestant Christian (24.6%). On average, patients reported general religiosity in the “fairly” (2) to “moderately” (3) range, and spiritual struggles in the “slightly” (1) to “fairly” (2) range. Patients reported perceived benefit of SPIRIT in the “fairly” (2) to “moderately” (3) range, representing positive results overall.

We found no significant differences in demographic variables between groups (

Table 1). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses, use of antipsychotic medications, electroconvulsive therapy, previous hospitalization, or safety concerns, such as active self‐harm/suicidality, or previous suicide attempts, between groups (

Table 1).

We also found no significant group differences in religious affiliation, or self‐reported religiosity variables including importance of religion, importance of spirituality, belief in God/Higher Power, active involvement in a faith community, or utilization of spirituality/religion to cope with difficult life circumstances or spiritual distress (

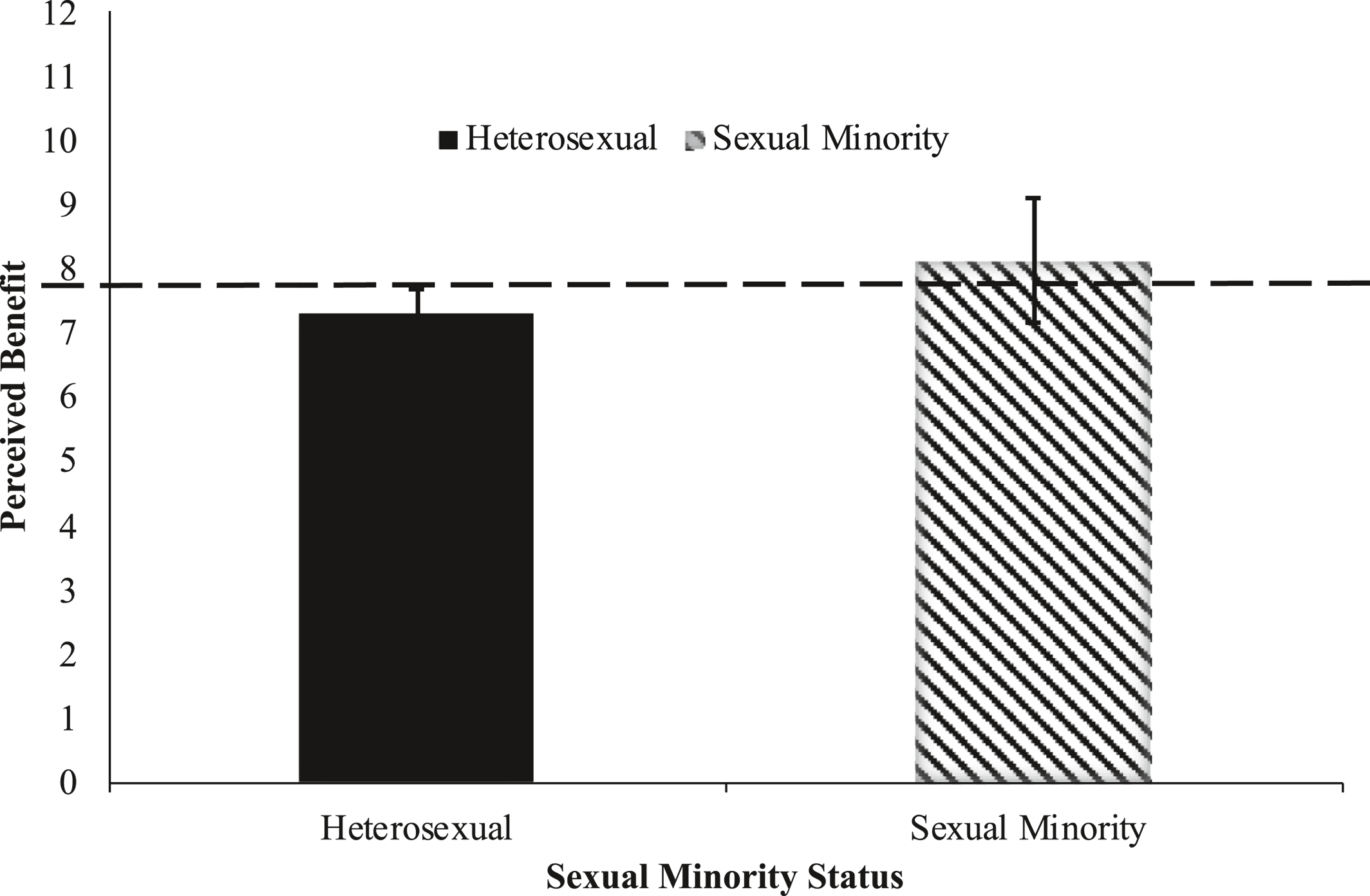

Table 2). With that said, we noted that 20% of the heterosexual patients identified as Catholic, whereas only 6.7% of the sexual minority patients identified as such. There were no significant groups differences in perceived benefit of spiritual psychotherapy (

Figure 1).

Following up on these analyses, we examined whether general spirituality/religion was associated with perceived benefit of SPIRIT, and failed to identify significant relationships in either group (sexual minority: r = 0.186, p = 0.508; heterosexual: r = 0.238, p = 0.060) or between spiritual distress and perceived benefit (sexual minority: r = 0.172, p = 0.539; heterosexual: r = 0.002, p = 0.989).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found no significant differences between sexual minority and heterosexual patients who self‐referred to SPIRIT. Specifically, patients were equivalent with regard to clinical severity, spiritual/religious characteristics, spiritual distress, and perceived benefit from SPIRIT. Additionally, spiritual/religious involvement and spiritual distress did not differentially predict perceived benefit from SPIRIT among sexual minority or heterosexual patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine responses to spiritually integrated therapy among sexual minority individuals. These findings suggest that sexual minority and heterosexual individuals may benefit equally from spiritually‐integrated therapy. More broadly, these findings underscore the importance of clinicians being open to exploration of relevant spiritual/religious topics with all patients, without assumption that such themes may be inherently problematic for sexual minorities.

While our results ran counter to hypotheses, there are several reasons why both sexual minority and heterosexual patients may have benefitted equally from SPIRIT. First, SPIRIT is a self‐referred treatment and all patients presented to the group on a voluntary basis. As noted above, Lefevor and colleagues' (

16) recent meta analyses concluded that sexual minorities tend to benefit from spirituality/religion when engagement is viewed as elective as opposed to coerced. The importance of preserving agency is perhaps no more critical than in an acute psychiatric treatment setting, where patients are inherently vulnerable, and this may have enhanced positive effects for sexual minority patients in our study. Along these lines, in one mixed‐methods study, Kubicek and colleagues (

28) observed how men who have sex with men had integrated religion and spirituality into their lives: Many reported that even when their religious communities or affiliations contained homophobic messages, they were still able to view their higher power as a source of comfort, and thereby found ways to create an “individualized spirituality.” It is quite possible that SPIRIT's flexible clinical approach may have helped facilitate individual spiritual growth.

Second, SPIRIT was provided in an environment that is supportive and inclusive of sexual minorities, and homophobic elements of religion were absent from treatment (i.e., no identities were discriminated against during this group, and discussion about identities were facilitated within a non‐judgmental space.) Prior to SPIRIT, sexual minority patients may not have had sufficient opportunity to adequately explore spiritual/religious issues—either within community or therapeutic settings—with affirmation of their sexual identities. While SPIRIT was not designed specifically for sexual minorities, by providing a safe space to discuss elements of spiritual/religious identity, SPIRIT may have functioned similar to Gay‐Straight Alliance (GSA) groups, which also provide a non‐judgmental space in which discussion about identity is welcomed. Previous research suggests that participation in GSA groups during young adulthood is associated with less distress around sexual orientation and also less religious incongruence (

29).

Third, it is possible that the sexual minority individuals who presented to SPIRIT were not struggling with religion related to their sexual identity, and other more spiritually distressed patients may have opted not to participate. Relatedly, patients who self‐referred to SPIRIT may have been more likely to come from affirming religious communities. Future studies should evaluate the relevance of SPIRIT and other forms of spiritual psychotherapy to a broader group of sexual minority patients, in order to evaluate these possibilities.

Interestingly, in the present study, we observed no significant differences between sexual minority and heterosexual patients in clinical diagnoses or suicidal thoughts or behaviors. This was likely due to a ceiling effect, given that the current study was conducted within an acute psychiatric setting. However, it also might have been related to the nature of a sub‐sample of acute psychiatric sexual minority patients who self‐refer for spiritually‐integrated treatment. Previous literature has suggested that religious affiliation can serve as a protective factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (

30), and such effects are particularly apparent within sexual minority groups as reviewed above. While this particular question was not the focus of this investigation, our findings warrant future research into the protective implications of religion on suicidal thoughts and behaviors for sexual minorities in an intensive outpatient setting.

There are several important limitations to the current study. Due to the limited sample size, we were unable to examine many aspects of intersectionality. Previous literature has shown that the effects of stress are complex, thus the stress of a white sexual minority patients is not comparable to that of sexual minority patients who identify as people of color (

27). These effects are even more nuanced, given that religious affiliation can be complex as well—both in terms of sexual identity (e.g., internalized homophobia) as well as socioeconomic status and privilege. Relatedly, being a religious minority (e.g., Muslim) could be yet another factor contributing to stress (

31,

32). Similarly, we were unable to compare different sexual orientations, which is a critical area for future research, given previous findings that bisexual individuals have worse mental health difficulties compared to gay and lesbian populations (

33). Nevertheless, the present study adds to the limited body of existing literature and suggests that sexual minorities may benefit from spiritual psychotherapy, under certain conditions.