Table 1 shows sample characteristics and study variables for the overall sample and by history of suicidality groups. Chi‐square tests revealed differences in sex, race, and history of AUD by history of suicidality groups, and follow‐up multinomial logistic regressions were conducted. Male participants were marginally less likely than female participants to endorse a history of suicide attempt (

p = 0.062). Relative to White participants, Black/African American participants were less likely to endorse a history of suicide ideation (

p = 0.004). History of AUD was strongly associated with history of suicide ideation and attempt. Relative to those without a history of AUD, individuals with a history of AUD were much more likely to endorse a history of suicide ideation only (70.7% vs. 31.5%;

p < 0.001) or a history of suicide attempt (82.8% vs. 31.5%;

p < 0.001). One‐way ANOVAs showed significant suicidality history group differences in COVID‐related stressors and clinical outcomes, in which individuals with a history of either suicide ideation only or suicide attempt reported elevated scores compared to those without any history of suicidality.

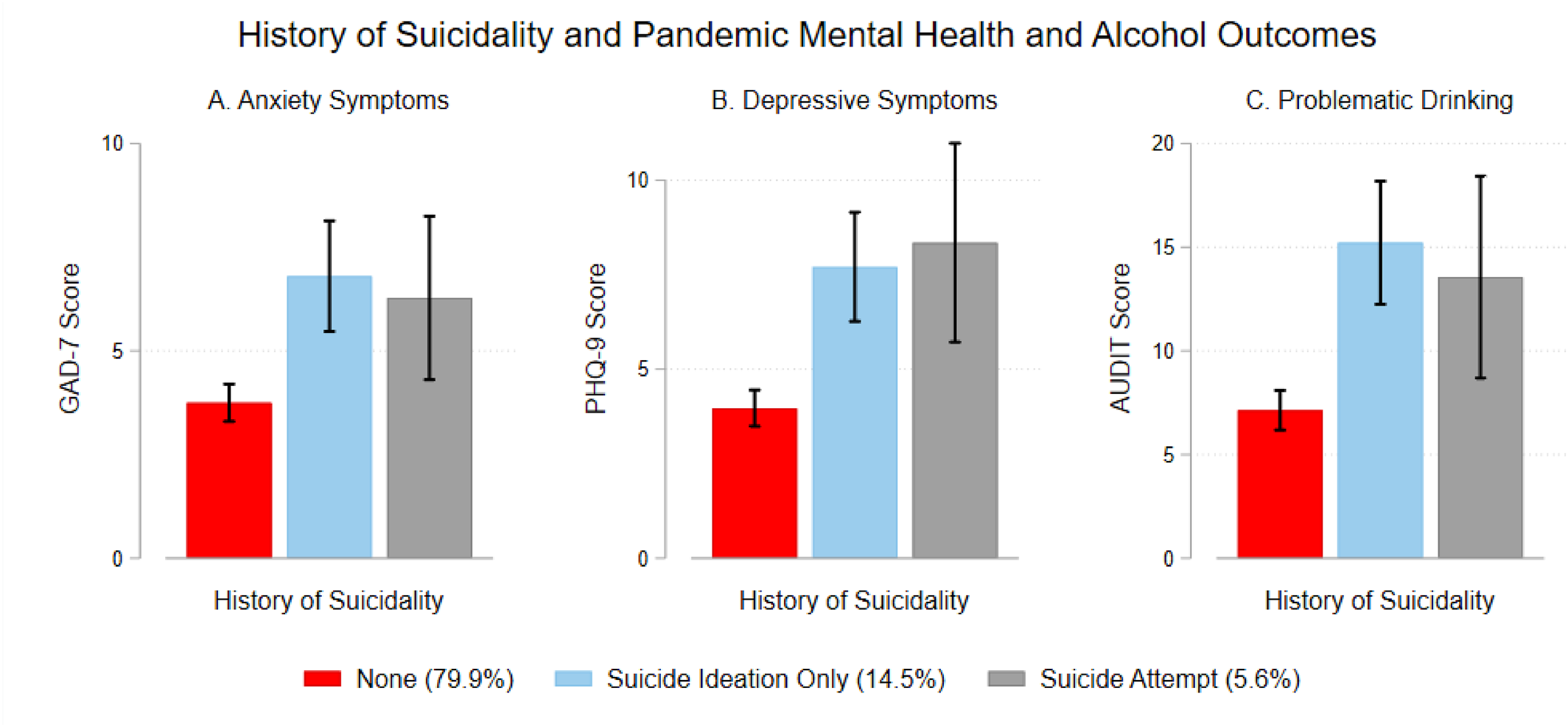

Figure 2 illustrates the longitudinal associations of suicidality history with anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and problematic drinking. Results from linear regression models showed that relative to individuals without any history of suicidality, those with a history of suicide ideation only reported higher anxiety symptoms (

b = 3.05, 95% CI = 1.85, 4.26,

p < 0.001), depressive symptoms (

b = 3.74, 95% CI = 2.42, 5.05,

p < 0.001), and problematic drinking (

b = 8.08, 95% CI = 5.46, 10.70,

p < 0.001). Similarly, individuals with a history of suicide attempt also reported higher anxiety symptoms (

b = 2.53, 95% CI = 0.68, 4.37,

p = 0.007), depressive symptoms (

b = 4.38, 95% CI = 2.36, 6.39,

p < 0.001), and problematic drinking (

b = 6.42, 95% CI = 2.41, 10.43,

p = 0.002).

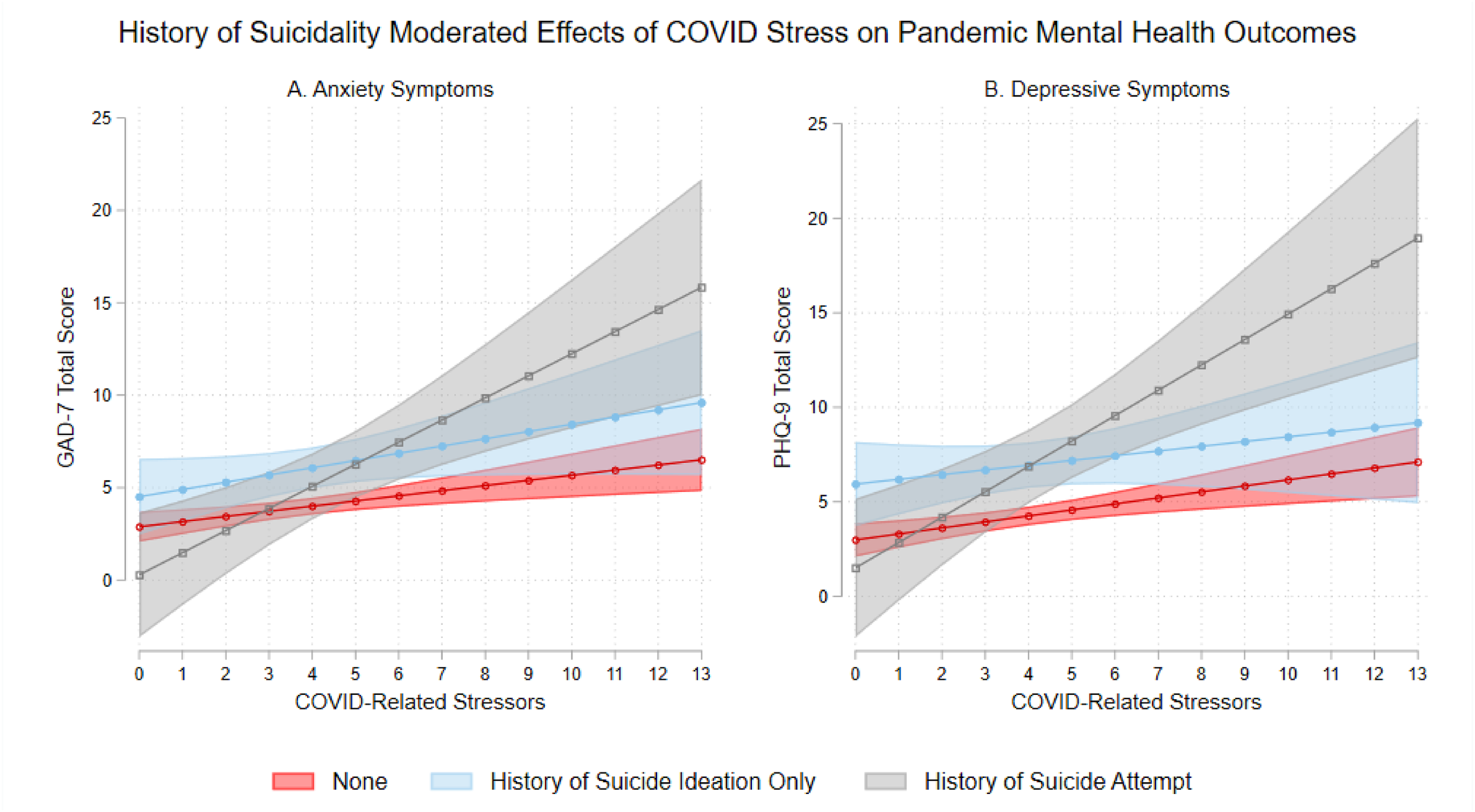

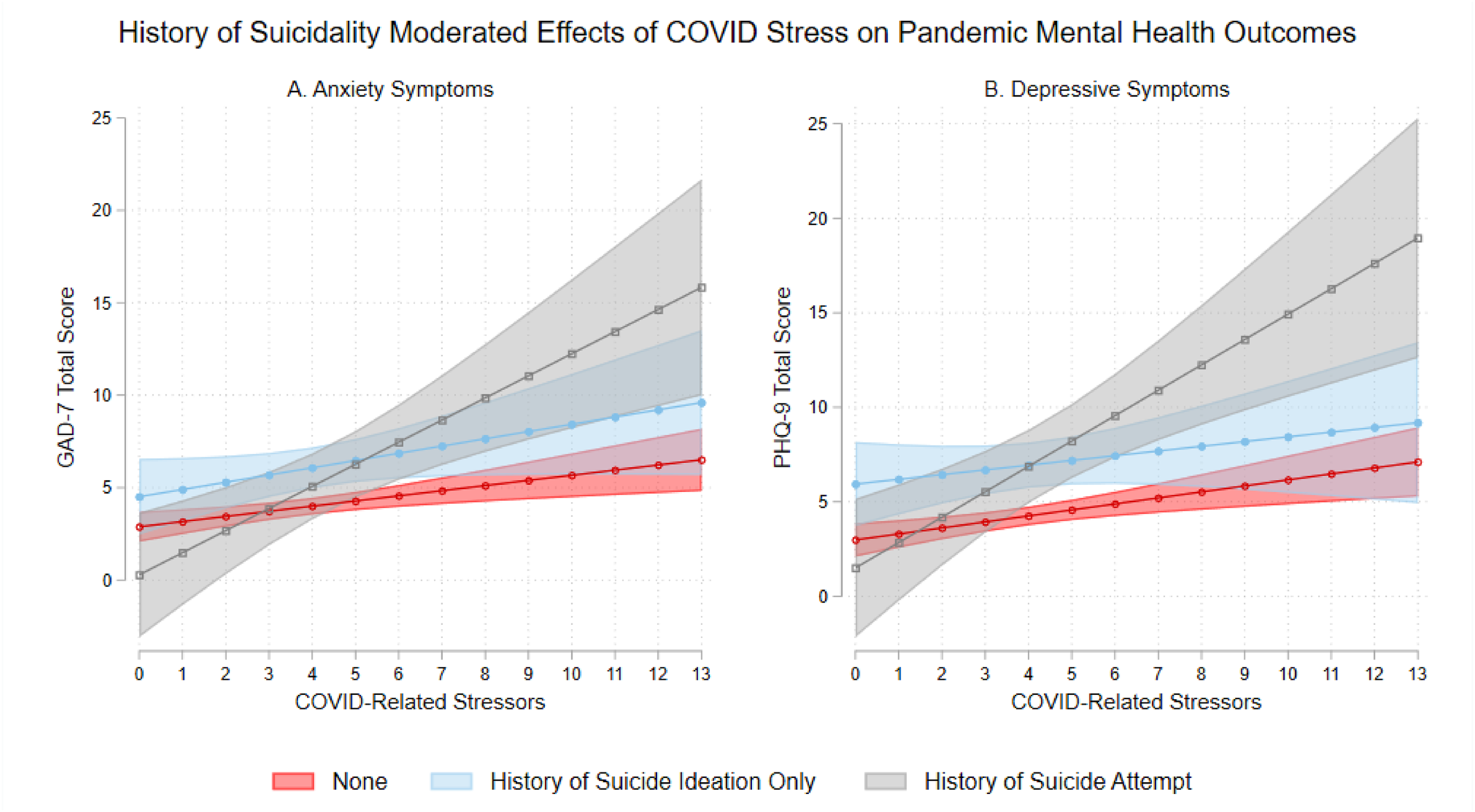

Table 2 shows the multiple regression models testing the interaction between COVID‐related stressors and history of suicidality on mental disorder symptoms and problematic drinking. The interaction between COVID‐related stressors and history of suicide attempt was significant for anxiety symptoms (

b = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.24, 1.60,

p = 0.008) and depressive symptoms (

b = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.29, 1.76,

p = 0.006). As shown in Table

S3, the simple slopes of COVID‐related stressors on mental disorder symptoms were significant among individuals without any history of suicidality (

b = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.46,

p = 0.002 for anxiety symptoms;

b = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.12, 0.51,

p = 0.001 for depressive symptoms), and the magnitudes of these associations were substantially stronger among individuals with a history of suicide attempt (

b = 1.20, 95% CI = 0.55, 1.85,

p < 0.001 for anxiety symptoms;

b = 1.34, 95% CI = 0.64, 2.05,

p < 0.001 for depressive symptoms). These interaction effects are visually illustrated in

Figure 3. Of note, due to relatively few participants in the history of suicide attempt group (

n = 29), the 95% CI bounds were wider for this group. As for problematic drinking, history of AUD was strongly associated with problematic drinking. COVID‐related stressors and later enrollment phases were also positively associated with problematic drinking. When the nonsignificant interaction terms were dropped in the final multiple regression model, history of suicide ideation was positively associated with problematic drinking (

b = 2.87, 95% CI = 0.75, 4.99,

p = 0.008), whereas history of suicide attempt was not associated with problematic drinking (

b = 0.58, 95% CI = −2.64, 3.79,

p = 0.724).