Social anxiety and depression are considered leading causes of disability worldwide. They are also associated with significant functional impairment, particularly occupational impairment, which is in turn associated with reduced wellbeing. (

1,

2,

3,

4) Importantly, both cross‐sectional (

5,

6,

7) and longitudinal studies (

8,

9) demonstrate bidirectional associations between depression and unemployment. For example, gaining employment is associated with lower depression 2 years later, whereas higher baseline depression is associated with lower likelihood of future employment. (

9) Social anxiety is associated with a lower likelihood of receiving and accepting job offers, (

10,

11) poor job performance (

12), increased work absences, (

13) and higher rates of terminations and resignations. (

14,

15) However, bidirectional associations between social anxiety and unemployment are untested. High comorbidity between depression and social anxiety (

16), though, suggests that a bidirectional relationship may similarly exist.

Possible mechanisms of these relationships could include avoidance behaviors due to fears of negative social evaluation or low self‐efficacy or motivation that inhibit effective work‐related behaviors (

17). Indicators of occupational impairment may, in turn, increase anxiety or depression, leading to further avoidance or withdrawal for fear of negative feedback or rejection. By contrast, repeated exposure to the workplace and positive performance reviews may decrease anxiety, akin to the effects of exposure therapy, (

18) and may also decrease depression via increased engagement in pleasant interactions or mastery‐related activities (

19).

In addition to the limitations of predominantly cross‐sectional examinations of unemployment, depression, and anxiety, much of the existing research analyzes employment as dichotomous (i.e., employed or unemployed). (

6,

8,

9) Number of hours worked may be a more sensitive index, depending on the relevant mechanisms underlying these relationships. For example, if exposure to social situations drives the relationship between social anxiety and employment, then one would expect a stronger effect for those who have spent more time in the workplace, and thus receive a higher “dosage.” Further, it is important to address these questions in unemployed or underworked clinical populations to understand how the challenges of mental health and unemployment may influence each other. This can then guide the development of interventions that effectively address both symptoms and occupational impairment.

To address these gaps, the current study used path analysis to examine bidirectional relationships between hours worked and symptoms of social anxiety and depression in a clinical population. This secondary data analysis used post‐intervention data from a larger treatment trial for job‐seekers with social anxiety disorder, many of whom reported elevated levels of depression. We hypothesized a bidirectional, inverse relationship between social anxiety and depression and hours worked, such that those who endorsed greater social anxiety and depression symptoms would subsequently work fewer hours. Additionally, we hypothesized that those who worked more hours would endorse lower subsequent levels of social anxiety and depression.

METHODS

Participants

Participants (

N = 250) were adults ages 18–60 with diagnoses of social anxiety disorder seeking vocational services at Jewish Vocational Services (JVS) centers in Detroit (JVS‐D) and Los Angeles (JVS‐SoCal). Data were collected as part of a multi‐site randomized controlled trial of a cognitive‐behavioral intervention (WCBT + VSAU) for reducing social anxiety symptoms and enhancing employment success among unemployed individuals with social anxiety disorder. (

20) Written informed consent was obtained from participants and secondary data analysis was conducted in compliance with Internal Review Boards at both sites. Further details about participants and study protocol are published elsewhere (

20).

The mean age of the sample was 44.56 (SD = 11.02). 59.2% of the sample identified as female, 39.2% as male, and 1.6% identified as neither male nor female. The racial distribution was 40.8% Black or African American, 35.6% White, 2.8% Asian/Asian American, 1.6% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 9.6% more than one race, and 9.2% other race not listed. Additionally, 16.4% of the sample identified as Hispanic or Latine. Our sample was notably diverse in that a substantial proportion of participants were homeless or had transient housing (52%), were experiencing suicidal ideation (40%), had a prior suicide attempt (16%), and had comorbid diagnoses of alcohol use disorder (24%), substance use disorder (23%), or antisocial personality disorder (17%). Furthermore, 50.8% of our sample had a current comorbid diagnosis of unipolar depression and over 95% had experienced at least one major depressive episode in their lifetime.

Measures

Outcome Measures

Social Anxiety Symptoms: Social anxiety was measured using the self‐report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS). (

21) This 24‐item scale assesses fear and avoidance of various social interaction and performance situations with separate ratings from “0” (none) to “3” (severely fears or usually avoids). The LSAS has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, convergent validity, and sensitivity to change following treatment. (

22) We observed excellent interitem reliability at the week 4 assessment (

α = 0.97).

Depression Symptoms: Depression was assessed using the eight‐item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ–8), (

23) a self‐report questionnaire where participants rate each of the DSM‐IV criteria for depression, excluding the suicidality item, from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day) as they pertain to the previous 2 weeks. Scores were totaled such that higher scores reflect greater depression symptom severity. The PHQ–8 has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability. (

24) We observed excellent interitem reliability at the week 4 assessment (

α = 0.90).

Hours Worked: Following conclusion of the intervention, from weeks 6 to 52 participants received text messages every two weeks asking them to estimate the number of hours they worked for pay each of the prior two weeks (e.g., at week 6, participants reported hours worked in weeks 5 and 6). We analyzed three epochs of time over the course of 48 weeks, using the average number of weekly hours reported for each epoch: average number of hours worked between weeks 5–12, 13–26, and 27–52. Data were not available during weeks 0–4, when the study intervention (WCBT + VSAU) took place.

Covariates

The following variables were included as covariates in the model due to the demonstrated relevance of each for both mental health and employment.

Psychosis: Psychosis was assessed at baseline using four items from the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), (

25) a semi‐structured clinical interview where interviewers rated 24 different symptoms, from 1 (not present) to 7 (extremely severe). These four items (hallucinations, unusual thought content, suspiciousness, and conceptual disorganization) composed the BPRS psychosis subscale (

25).

Substance Use: Alcohol and substance use disorders were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (

26) at baseline. These disorders were coded as a dichotomous variable, where “1” indicated the presence of either disorder and “0” indicated the absence of an alcohol or substance use disorder.

Other Comorbid Anxiety Disorder: Comorbid panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and post‐traumatic stress disorder were assessed using the MINI at baseline. These disorders were coded as a dichotomous variable, where “1” indicated the presence of any of the disorders, and “0” indicated the absence of all three.

Homelessness: Participants self‐reported their housing status at baseline, which was coded as a dichotomous variable indicating homeless/at risk for homelessness (‘0’) and stably housed/not at risk for homelessness (‘1’).

Racial Minority Status: Participants self‐reported their race and whether they identified as Hispanic and/or Latine at baseline. Participants who identified as non‐white or Hispanic/Latine were coded as “1” and participants who identified as white and non‐Hispanic/Latine, or non‐minoritized, were coded as “0.”

Household Income: Participants self‐reported household income at baseline by choosing from six different income brackets, ranging from “less than $10,000” to “$80,000 or more.”

Intervention Condition: Participant intervention condition was coded as a dichotomous covariate, with “1” denoting participants in the WCBT + VSAU condition and “0” denoting those in the VSAU‐alone condition.

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using RStudio Version 9.0 and the lavaan package (

27) with full information maximum likelihood to address missing data. Our primary interests in the current study were the bidirectional relationships between both social anxiety symptoms and hours worked and depression symptoms and hours worked over the course of the study period. These proposed relationships were tested in two separate models via path analysis, using data from week 4 (post‐intervention), week 12, week 26, and week 52 of the study. We chose to test two separate models for social anxiety and depression because correlations between social anxiety and depression across the four timepoints ranged from 0.44 to 0.58, indicating substantial multicollinearity. (

28) Social anxiety in Model 1 and depression symptoms in Model 2 were included as both predictors and outcomes. Average weekly hours worked, reported between weeks 5–12, weeks 13–26, and weeks 27–52, were also included as both predictors and outcomes. See

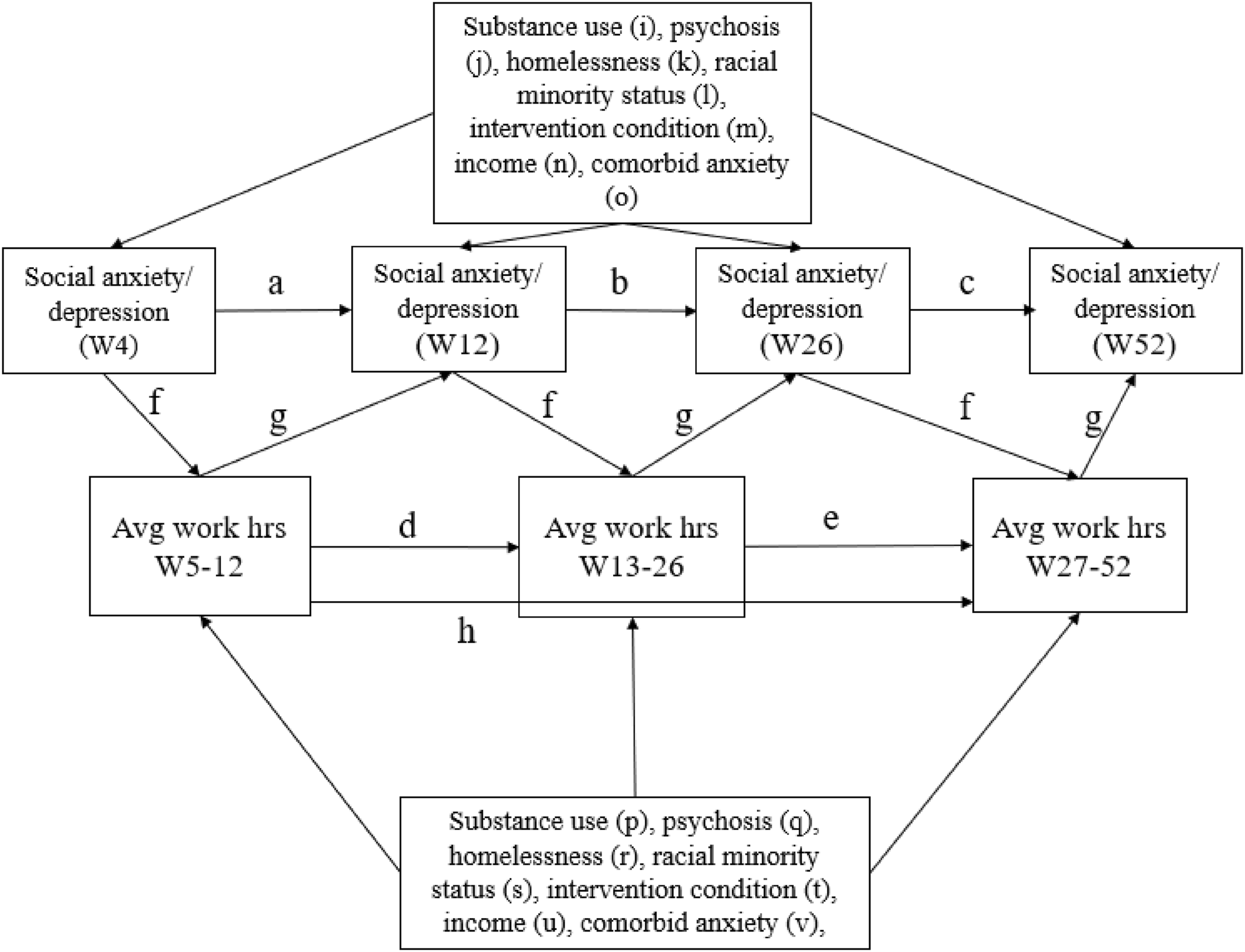

Figure 1 for visual representation of the models and paths.

Outcomes were regressed onto equivalent measures at the previous epoch (i.e., social anxiety symptoms at Week 12 were regressed onto social anxiety symptoms at Week 4) for social anxiety and depression symptoms (paths a–c) and work hours (d, e). Hours worked were regressed onto social anxiety/depression symptoms (f) at the previous epoch. Social anxiety and depression were regressed onto hours worked (g) at the previous epoch. Hours worked at the final epoch (Weeks 27–52) were regressed onto hours worked at the first epoch (Weeks 5–12) (h). Additionally, social anxiety and depression (i–o) and hours worked (p–v) were regressed onto the covariates in the model, substance use, psychosis, homelessness, household income, intervention condition, and comorbid anxiety disorders.

Participants who received the intervention (WCBT + VSAU) were expected to have lower levels of psychopathology, specifically social anxiety, following treatment and had the opportunity to gain skills (e.g., cognitive restructuring) that may have allowed them to approach social situations at work more effectively. Therefore, sensitivity analyses were conducted to separately test the main effects in WCBT + VSAU and VSAU‐alone and compare the two (see supplemental materials for further information). However, it is notable that the parent study did not find significant differences in number of hours worked between the two treatment conditions (

20).

We assumed stationarity in all relationships across time. Both of our constrained models demonstrated adequate model fit. See supplemental materials for additional information regarding stationarity assumptions and model fit indices.

DISCUSSION

The current study examines the relationship between hours worked and symptoms of social anxiety and depression in a diverse sample of unemployed and underworked individuals with social anxiety disorder. We hypothesized that hours worked would negatively predict future symptoms of social anxiety and depression, and symptoms of social anxiety and depression would negatively predict hours worked. We found partial support for our hypotheses. After controlling for previous number of hours worked, household income, homelessness, psychosis, substance use, racial minority status, and prior intervention condition, we found that levels of social anxiety and depression each negatively predicted hours worked. Specifically, individuals who endorsed higher levels of social anxiety or depression reported fewer hours worked in the subsequent epoch. This supports our initial hypothesis and aligns with previous research suggesting that depression predicts later unemployment (i.e., fewer hours worked) (

9) as well as extends findings to include social anxiety. This finding underscores the functional impairment that ensues from social anxiety and depressed mood. (

29,

30,

31) Potential explanatory factors may be avoidance or withdrawal behaviors that often characterize and maintain social anxiety and depression, though future research should further investigate (

32,

33).

We did not find support for our hypothesis that hours worked predicted social anxiety and depression. This finding is inconsistent with previous research which has shown that employment status predicts subsequent depression. (

6,

8) However, these prior studies examined relationships over the span of several years rather than weeks. Thus, perhaps the effect of depression upon functional impairment takes longer to emerge than the eight‐to 26‐week gaps examined herein. Additionally, previous studies investigated the presence or absence of employment, rather than hours worked (

7,

8,

9) such that their observed effects may be due to employment itself (e.g., receiving benefits, having a steady salary) rather than the specific number of hours worked.

Several covariates were found to have significant associations with our main outcomes. The finding that participants who identified as racial and ethnic minorities reported fewer symptoms is in line with previous research that demonstrates that individuals who identify as white endorse anxiety disorders at a higher rate than Black, Asian, or Hispanic Americans (

34). However, this result may also reflect a discrepancy in how disorders are conceptualized rather than lower rate of social anxiety in Non‐White and Latine individuals. The finding that individuals with comorbid anxiety disorders reported higher depressive and social anxiety symptoms is in line with high rates of comorbidity among these disorders (

35).

Additionally, to our knowledge, there is no evidence in the literature to support the finding that individuals who met criteria for alcohol and substance use disorders at baseline would work more. It is possible that this finding is spurious, and that the low range of hours worked may not be sufficient to capture any real associations. Similarly, the finding that homelessness was negatively associated with social anxiety symptoms may also be explained by these limitations. Additionally, the finding that treatment condition was not significantly associated with symptoms is in line with the finding from the parent study, which found no differences between interventions in social anxiety symptoms as measured by the LSAS after 4 weeks (

36). Regarding the other nonsignificant covariates (psychosis and baseline household income), it is similarly possible that the low range of hours worked or sample size may not have been sufficient to capture real associations. Additionally, these covariates were measured once at baseline and values may have changed throughout the course of the year‐long study.

The present study had several notable strengths. Our study has substantial external validity, given that the sample was racially and ethnically diverse and participants had numerous comorbidities, including psychosis and substance use disorders, which are often exclusionary in other studies. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine bidirectional relationships between anxiety and depression and hours worked in a longitudinal repeated‐measures design. We had high frequency measurement of hours worked every 2 weeks, which is likely less susceptible to errors and reporting biases than estimates over longer intervals or at a single point in time.

This study also had several limitations. As employment is often not within an individual's control, working no or few hours each week could be indicative of, for example, a dearth of work opportunity despite job search efforts. The sample size (

N = 250) is relatively small for path analysis, a factor that was compounded by substantial attrition rates. However, attrition was as expected for a diverse sample with high rates of homelessness, especially given that individuals typically use JVS services for only a few weeks at a time. The sample size may impact replicability of findings, although our high interitem reliability and satisfactory model fit indices would suggest that it was sufficient. (

37) Nonetheless, future studies with larger sample sizes should further investigate these questions. This sample is further limited in that the mean number of hours worked was relatively low (ranging from 13.18 to 18.91 across time). A sample with a broader range and hour average of hours worked may be a more appropriate test for our study's hypotheses. Additional covariates, such as job satisfaction or content of interpersonal interactions at work, may be important to consider in future research since changes in symptoms could also be driven by whether the work is intrinsically motivating or rewarding. (

38) Further, while our study achieves temporal precedence and our models account for numerous competing explanations, we cannot guarantee causal inference as our data represents naturally occurring rather than experimentally manipulated variables. Depression and anxiety symptoms and hours worked were only measured by self‐report. Objective data regarding hours worked was not available due to the lack of a centralized employment database in either state where the research was conducted. Finally, half of the participants received a specialized intervention targeting work‐related social anxiety before data collection of interest for the current analyses. This intervention could have differentially impacted the relationships between symptoms and hours worked. However, sensitivity analyses found no difference between treatment conditions, and this intervention was brief with a limited focus of attention on social anxiety symptoms.

Clinically, findings suggest that clinicians should monitor employment‐related factors, such as work attendance and time spent working, when treating patients with depression or social anxiety, as symptoms may lead to significant functional impairment. Furthermore, this study highlights the potential importance of mental health interventions to simultaneously address occupational concerns. Since symptoms of social anxiety or depression may serve as a barrier to seeking or maintaining employment, effective treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, (

39,

40) may indirectly help individuals obtain or maintain employment. Clinicians may also utilize therapeutic interventions that directly incorporate employment‐related activities, such as social anxiety exposures about job interviews or conversations with co‐workers, or scheduling meaningful, work‐related activities as part of behavioral activation for depression. Such interventions may decrease both symptoms and barriers to maintaining employment, thus also directly decreasing functional impairment. While the parent study investigating WCBT did not find long‐term differences between conditions, future research should aim to increase the effectiveness of this style of intervention, for example, by applying a more transdiagnostic focus.

In conclusion, social anxiety and depression symptoms negatively predicted number of hours worked in a clinical, underworked sample, while hours worked did not predict social anxiety and depression symptoms. Thus, future interventions should consider addressing mental health as a means of increasing employment.