Patients with mental health or substance abuse problems increasingly are presenting to emergency departments. They accounted for 12.5% of 95 million emergency department visits in 2007, compared with 5.4% of all visits in 2000 (

1). Reasons for this burgeoning use of the emergency department include the lack of appropriate care elsewhere (

2). For example, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds was 524,878 in 1970 but only 211,199 in 2002 (

3).

The increase in utilization of the emergency department has been accompanied by longer visits, particularly by individuals seeking mental health care. Duration of all emergency department visits increased at an annual rate of 2.3% from 2001 to 2006, but the average length of visits to the emergency department for mental health problems exceeded that of all other visits by 42% during the same time period (

4). The median time spent in the emergency department was 2.6 hours for all patients in 2006, compared with 5.5 hours for a sample of 400 psychiatric patients at one of eight emergency departments (

5,

6).

Wait times in the emergency department that exceed six hours contribute to crowding, which has a negative impact on patient safety by preventing new patients from being seen and increasing patient walk-outs (

2,

7). A recent national survey by the American College of Emergency Physicians confirmed that nearly 80% of emergency departments boarded psychiatric patients who were not admitted as inpatients because of a lack of space (

8).

From clinical experience, it has been observed that extended lengths of stay—defined as stays lasting 24 or more hours—for psychiatric patients not only are increasing but are especially problematic in terms of patient satisfaction and use of hospital resources (

9). A retrospective, case-control study conducted in Massachusetts, the site of the study reported here, provided the best available information about the rate of extended length of stay in emergency departments among psychiatric patients. The study matched 206 psychiatric patients with lengths of stay of 24 hours or more with 206 patients in a control group at a single academic medical center beginning in July 2002 for a 12-month period. It found that 3.8% of psychiatric patients experienced extended lengths of stay in the emergency room. Four factors significantly predicted extended lengths of stay—lack of insurance, disposition to an inpatient unit, and suicidal or homicidal ideation. However, implementation of mandatory health care insurance for all state residents as of April 2006 has eliminated one of the risk factors for extended stays (

10).

This article describes a prospective cohort study of demographic, clinical, and institutional characteristics associated with extended length of stay among psychiatric patients who sought care at one of five general hospital emergency departments that were part of an integrated health care system in Massachusetts. At the time of the study, only 2.6% of state residents were uninsured.

Methods

Emergency department psychiatric consultations at one of five general hospitals that are part of an integrated health care system in Massachusetts were studied. Two hospitals are academic medical centers, and three are community hospitals. Cases were eligible for inclusion if the patients were adults aged 18 years or older, presented with a primary psychiatric problem or complaint, and had a psychiatric consultation completed and documented. Patients who presented for psychiatric prescription refills or for whom doctors sought a “curbside” psychiatric opinion were not included.

Each hospital was asked to collect data on approximately 200 consecutive, eligible cases beginning at different months from June 2008 through May 2009. The samples from each hospital represented 31% to 75% of all eligible cases for the specific time period. The hospitals offered psychiatric consultations in the emergency department according to one of three overall methods. [Methods used by the hospitals for offering psychiatric consultation are summarized in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Information about patients' psychiatric consultations was recorded prospectively on a log by the evaluating clinician. Data collected included a patient identifier to allow for subsequent medical record review, date of consultation, and the disposition decision. Electronic and paper medical records were subsequently abstracted for patient demographic and clinical information, such as chief complaint, use of toxicology screening or diagnostic imaging, and involuntary commitment status before and after the psychiatric evaluation. Chief complaints were assigned into six problem categories, including somatic complaints, for example, back pain; any aspect of suicide, for example, ideation; mental health, for example, auditory hallucinations; behavior change, for example, onset of new aggressive behavior; substance use, for example, intoxication; and a service request, for example, psychiatric evaluation.

Patients may have had more than one chief complaint. Length of stay in the emergency room, defined as the interval between presentation to triage and discharge, was obtained from the electronic and paper medical records as well. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of each hospital.

Data were analyzed using the SAS statistical package, version 9.2. Simple descriptive statistics were calculated and reported as percentages, means with standard deviations, or medians. Total length of stay in the emergency department was calculated by subtracting the time of admission from the time of discharge. Patients with lengths of stay of 24 or more hours were compared with those with shorter stays by using chi square, parametric (t test), or nonparametric (Wilcoxon test) tests of significance as appropriate.

Results

Complete data were available for 1,076 (98%) of 1,092 cases collected. A total of 90 (8%) of the 1,076 psychiatric patients had stays of 24 or more hours (extended-stay patients). Their median length of stay was 30.6 hours, and the mean±SD was 36.9±18 hours (range 24–168.6 hours, or one to seven days). For the remaining 986 patients (92%), the median length of stay was 7.6 hours, and the mean was 9.1±5.3 hours.

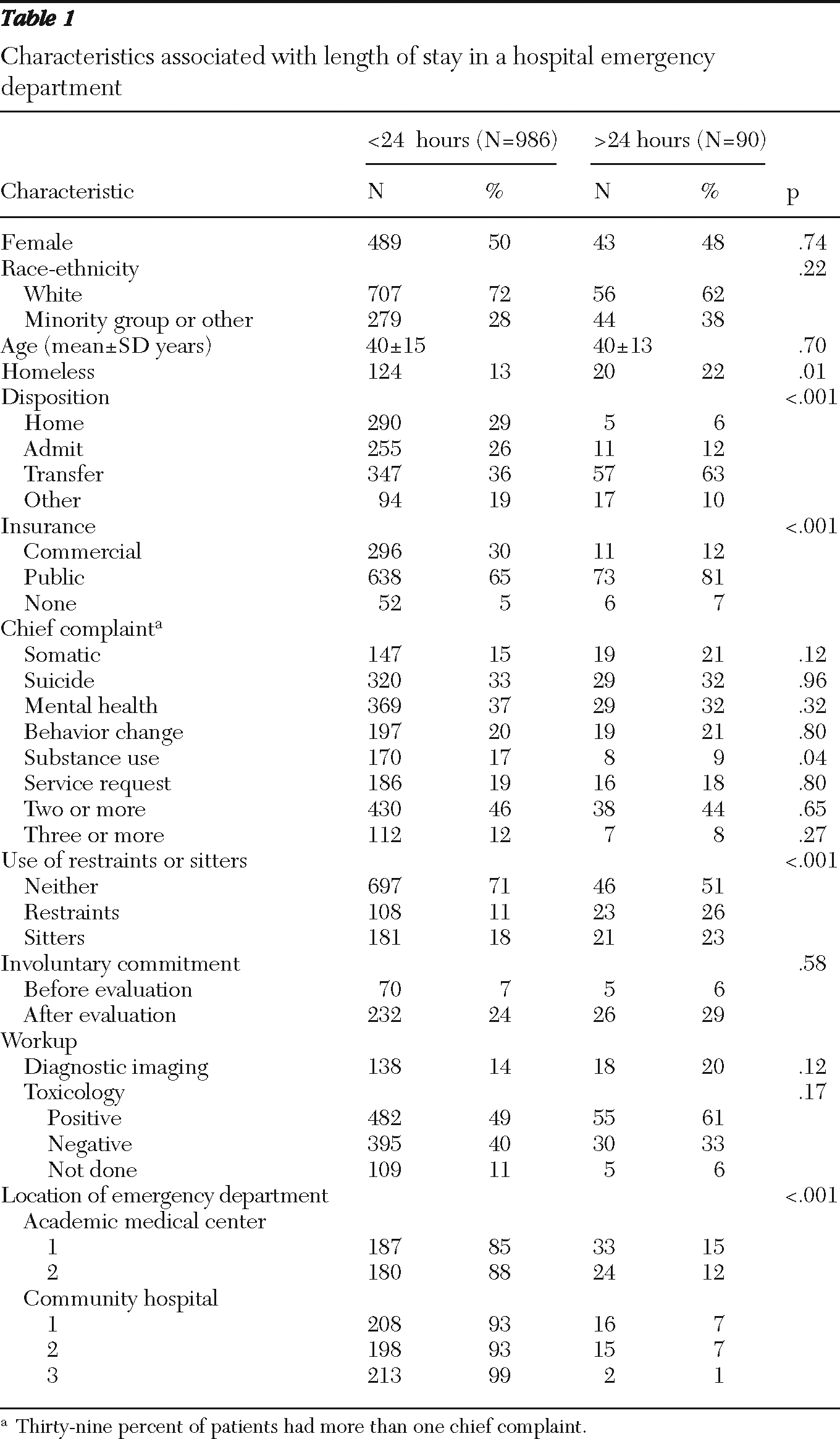

Patients' characteristics and their relationship to length of stay are summarized in

Table 1. Extended-stay patients were more likely to be homeless (22% versus 13%, p=.01), to be transferred for inpatient admission elsewhere (63% versus 36%, p<.001), to have public insurance (81% versus 65%, p<.001), and to have been restrained or watched by a sitter during their visit (49% versus 29%, p<.001). They were less likely, however, to have substance use as an initial complaint (9% versus 17%, p=.04).

Academic medical centers had significantly higher proportions of extended stay patients than the community hospitals (12% and 15% versus 1%, 7%, and 7%, respectively; χ2=32.1, df=4, p<.001). Otherwise, the two groups of patients did not differ in terms of gender, race, mean age, number of chief complaints, involuntary commitment status before or after evaluation, and types of diagnostic workup (imaging and toxicology screening) in the emergency department.

Discussion

Nearly one in 12 adult patients receiving psychiatric consultations in the study sample stayed in the emergency department for 24 hours or more (median=31 hours). This rate (8%) is twice the rate reported for psychiatric patients evaluated at an academic medical center in the same state between 2002 and 2003. That hospital was one of the five included in this study.

To put our psychiatric patients' experiences into context, only .4% of the nearly 124 million emergency department visits in 2008 nationwide lasted 24 or more hours (

5). Similarly, the majority of our patients had longer median lengths of stay (7.6 versus 2.6 hours), higher rates of hospital admission (25% versus 13.4%), and higher rates of transfer to a different hospital (37.5% versus 1.7%) compared with all patients who made visits to emergency departments in 2008 (

5).

As in other studies, characteristics positively associated with extended length of stay were homelessness and transfer for psychiatric care elsewhere (

4,

9). The use of restraints or sitters, public insurance, and the specific hospital where the patient presented were also positively associated with extended stay. A novel finding, that a chief complaint involving substance use problems was negatively associated with having an extended stay, needs replication by others.

Possible explanations of the findings include both clinical and systemic reasons (

9–

11). For instance, a homeless patient or one who needed restraints or sitters may have required more time to secure an appropriate disposition or to achieve clinical stability. Transfer to another hospital would require multiple, potentially time-consuming steps, beginning with ascertaining bed availability, securing insurance approval, and arranging for transfer (

4). A patient presenting with substance use issues was less likely to have an extended stay, possibly because the acute effects of intoxication resolved in less than 24 hours and the patient could be discharged safely.

This study took place when only 2.6% of the state's residents were uninsured (

9,

10), and more than 90% of patients in the study sample had health insurance. The high rate of insurance among the study sample may explain why age, gender, and race were not associated with extended stays. However, significantly higher proportions of those with public insurance had extended-stay status, a finding that may suggest that they had more problematic access to care after the emergency department visit than the privately insured patients. Differences in the rate of extended-stay patients by hospital may reflect case mix and volume in the emergency department as well as access to in-house psychiatric hospital beds, which ranged from none to 43. Indeed, the two hospitals with the most extended-stay patients had the fewest inpatient psychiatric beds.

Study limitations included the sampling strategy, whereby each hospital's emergency department was asked to collect data on the basis of consecutive presentations of patients who received a psychiatric consultation. Because the rate of sampling varied from 31% to 75%, the samples may not have been entirely representative of patients who received a psychiatric consultation. However, all key variables such as total time in the emergency department were verified by chart review. Given that other studies have demonstrated that psychiatric disorders are underdiagnosed among emergency department patients, perhaps some patients were not included because they did not receive a psychiatric evaluation (

12).

Information about staffing and volume in the emergency department was not collected for each visit; however, because a patient's stay could span several shifts, it would have been difficult to know when to measure staffing and volume. Information on neither concurrent inpatient psychiatric bed availability nor the patients' psychiatric treatment status at the time of emergency department visit was known. Future studies to evaluate extended emergency department stays should include larger and even more representative samples.

Strengths of this study include its prospective design, use of data from multiple corroborative sources, adequate sample size, and inclusion of emergency departments in both academic medical centers and community hospitals. Other recent studies about psychiatric patients in the emergency department did not emphasize length-of-stay issues or intentionally “trimmed” cases exceeding 21 hours (

4,

6). Thus our study is one of only a few that specifically focused on psychiatric patients—nearly all of them individuals with health insurance—who stayed 24 or more hours in an emergency department.

Conclusions

It appears that having health insurance alone was insufficient to ensure timely access by psychiatric patients to treatments after an emergency room visit. In particular, those with public insurance waited longer, suggesting that insurance reform efforts must also address treatment capacity (

10).

The lack of established benchmarks in the emergency department care of psychiatric patients, such as the number of visits lasting 24 or more hours, has been considered an impediment to quality assurance and performance improvement (

6). Compared with the “average” patient at emergency departments nationwide, the psychiatric patients in this sample waited three times longer, had four times the rate of admission or transfer, and were 20 times more likely to stay at least 24 hours. As such, results from this study will serve as the basis for data-driven efforts to improve the experience of patients within our health care network who require psychiatric consultation.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by the Partners Psychiatry and Mental Health Division of Health Services Research and grant K-24-AA000289 to Dr. Chang from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors thank Kenneth J. Sklar, Ed.D.

The authors report no competing interests.