For many patients with schizophrenia, the course of illness is characterized by frequent relapses with exacerbations of psychosis, often resulting in the need for rehospitalization (

1). Patients with a history of relapse have been shown to have a more complex illness profile, associated with more severe psychopathological symptoms, substance use, impairments in functioning and poor adherence to treatment (

2). Research applying recently proposed consensus definitions of outcome to examine the association between the status of patients with schizophrenia at hospital discharge—such as whether they have responded to treatment and whether their symptoms are in remission—and subsequent relapse is scarce.

In addition, clinical implications from earlier studies are limited because many focused only on first-episode patients or used data from randomized controlled trials known to exclude severely ill or suicidal patients. Another difficulty for researchers in this field is the lack of a consensus definition and generally accepted criteria for relapse. For example, a recent review that compared the relapse prevention potential of various antipsychotics noted that 11 different criteria were used in 17 studies (

3). In this study we used a broad definition of relapse to examine relapse in a heterogeneous group of patients in order to reduce potential limitations on our findings.

Methods

Data were collected as part of a multicenter naturalistic follow-up study, the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. The study was conducted at 11 university-affiliated psychiatric hospitals and three non-university-affiliated psychiatric hospitals. All patients between the ages of 18 and 65 who were admitted to one of the hospitals between January 2001 and December 2004 with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder according to DSM-IV criteria were selected for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were a head injury, a history of major general medical illness, and alcohol or drug dependence. All study participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees. After discharge patients were followed up for assessment at specified time points. The study reported here used data from the one-year follow-up assessment.

DSM-IV diagnoses were verified by clinical researchers. Information was collected on sociodemographic characteristics and on variables related to illness course and to attitude toward treatment and treatment adherence by using standard forms. Symptom severity was assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS) and the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD-17); higher scores on both instruments indicate greater illness severity. Extrapyramidal symptoms were examined with the Simpson-Angus Scale. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) were used to evaluate functioning. The short version of the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptic Treatment Scale assessed well-being. To evaluate the patient's premorbid adjustment the subscale for premorbid social-personal adjustment from the Phillips Scale was employed. The instruments were administered within the first three days after admission, biweekly during the patient's hospital stay, at discharge, and at follow-up. All raters had been trained in use of the scales. A high interrater reliability was achieved (intraclass correlation<.8).

Patients were categorized as experiencing or not experiencing a relapse. Relapse was defined by using two items from the standard forms. The first item evaluates an acute exacerbation of the illness, and the second item explicitly examines rehospitalization because of a worsened psychopathological condition. A positive rating in for either item was defined as a relapse.

The outcome of inpatient treatment was defined as a 50% improvement in PANSS total score from hospital admission to discharge. Remission was determined by the consensus criteria proposed by the PANSS developers—a score of 3 or less of the following items for six months: delusions, unusual thought content, hallucinatory behavior, conceptual disorganization, mannerisms and posturing, blunted affect, social withdrawal, and lack of spontaneity. The time criterion for remission was not considered at discharge if the patient had been hospitalized for six months or less.

First, univariate tests were used to compare patients with and without a relapse during the year after discharge. All variables with a p value of <.10 in the univariate analysis were tested as predictors of relapse by two methods: logistic regression analysis and classification and regression tree (CART) analysis. The discriminative ability of the regression model was evaluated by using a receiver-operating characteristic curve. The area under the curve (AUC) is a measure of the overall discriminative power. An AUC value of .5 indicates no discriminative ability, and an AUC value of 1.0 indicates perfect discriminative power. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical program R2.11.1.

Overall, 474 patients were enrolled in the naturalistic multicenter study. Forty-six patients dropped out for various reasons, 28 were discharged from the hospital within seven days of admission, and 167 dropped out during the acute treatment phase and follow-up. Patients who dropped out were significantly older than patients who did not (p=.006) and scored significantly lower at discharge on the PANSS total score (p<.001). The two groups did not differ in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Because of missing PANSS data at the one-year follow-up assessment, 33 patients were excluded. Thus data were analyzed for a sample of 200 patients.

Results

The sample included 107 men and 93 women. The mean±SD age was 36.3±10.1 years, and the mean duration of illness was 8.3±9.4 years. The mean number of lifetime hospitalizations was 3.4±5.1. The mean age at first treatment was 28.1±9.6 years. At one-year follow-up 50 patients (25%) were receiving first-generation antipsychotics, 130 (65%) were receiving second-generation antipsychotics, 18 (9%) were receiving first- as well as second-generation antipsychotics, 22 (11%) were receiving tranquilizers, and 27 (14%) were receiving mood stabilizers. Forty-six patients (23%) were also receiving antidepressants.

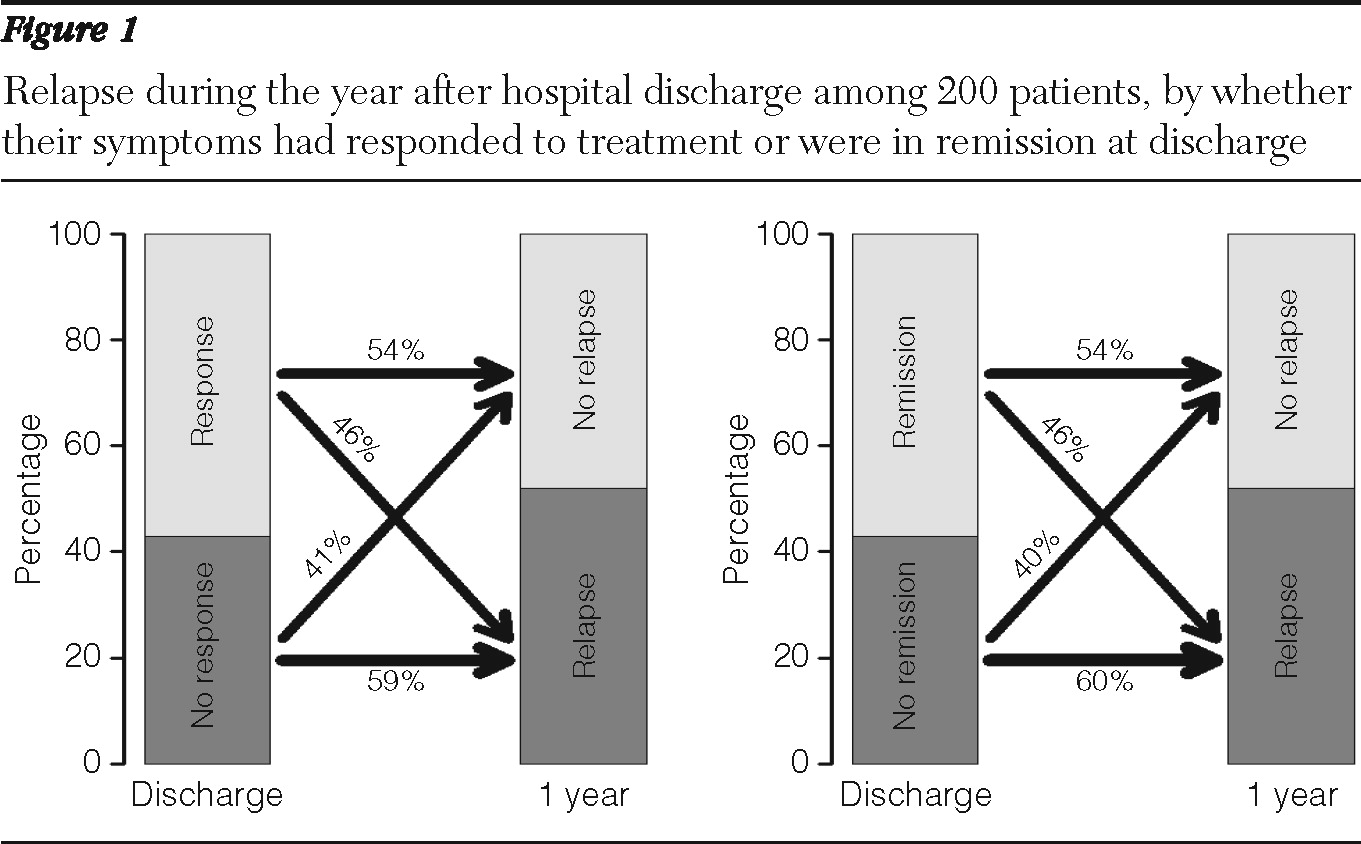

From hospital discharge to the one-year assessment, no significant change in patients' psychopathology, functioning, occurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms, and subjective well-being was observed. At discharge, 114 patients (57%) were classified as treatment responders, and symptoms were in remission for 114 patients (57%). At follow-up, 108 (54%) were classified as responders, and symptoms were in remission for 102 (51%) (

Figure 1).

A total of 104 patients (52%) had at least one relapse during the follow-up period, and 34 (17%) had more than one. At the one-year follow-up assessment, those who had experienced a relapse scored significantly higher on the PANSS total score (p<.001) and all PANSS subscale scores; they also had significantly greater impairments as measured by the GAF and SOFAS (p<.001). Among patients who experienced a relapse, 78 (75%) were hospitalized as a result of the exacerbation of their illness, and 26 (25%) were treated for the relapse in an outpatient setting.

Patients who had a relapse during the follow-up period were significantly less likely to be employed at hospital discharge (p=.002). In addition, those with a relapse were significantly less likely at discharge to be treated with a second-generation antipsychotic (p=.04) and had a significantly worse attitude toward treatment (p=.007). Also, patients who had a relapse were significantly more likely to report side effects (p<.001) at discharge, even though no significant between-group differences were observed at discharge in the defined daily dose of the second-generation or first-generation antipsychotics. Furthermore, patients who relapsed scored significantly higher at discharge on the PANSS total score (p=.02), the PANSS negative subscore (p=.02), and the HAMD-17 total score (p=.01), indicating more negative and depressive symptoms. Patients whose symptoms were not in remission at discharge were significantly more likely to relapse within the year after discharge than those whose symptoms were in remission at discharge (p=.05) (

Figure 1).

Four significant relapse predictors, as measured at hospital discharge, were identified: a higher HAMD-17 score (p<.001), more side effects (p<.001), a worse attitude to treatment (p=.002), and not having a job (p=.01). The prediction model reached significance (p<.001), with satisfactory predictive power (AUC=.76). The CART model confirmed that reporting more side effects at discharge (p<.001) and having a worse attitude toward treatment adherence at discharge (p=.007) were significant predictors of relapse. Significant predictors by CART analysis at discharge also included a higher PANSS negative subscore (p=.04) and an independent living situation (p<.001).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors that predicted relapse among patients with schizophrenia so that these variables could be monitored during treatment and specific strategies could be adopted to prevent relapse. In our sample, 52% of patients had a relapse in the first year after hospital discharge—an alarmingly high proportion. One possible explanation is that the sample included chronically ill patients with a history of distinct cycles of relapse. In addition, this study was observational, and patients received only monthly telephone calls during follow-up. Unlike randomized controlled studies, no extensive visits or interventions were provided. However, the relapse rate in our study is comparable to the rate of 42% found in a study of relapse among patients taking oral antipsychotics (

4). In a study that compared maintenance treatment of first-episode patients with risperidone and haloperidol for one year and that defined relapse as a marked clinical deterioration, Gaebel and colleagues (

5) found that no relapses occurred. This finding may be at least partly explained by the inclusion of only first-episode patients in the sample. In line with the findings of that study, our results indicated that patients experiencing a first episode had a lower risk of relapse during follow-up; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance, which may be explained by the small sample of first-episode patients and therefore the limited statistical power in our study.

As others have found, depressive symptoms at hospital discharge in our study were significant predictors of relapse during the one-year follow-up. In a three-year prospective, observational study in which 2,228 patients with schizophrenia were examined at 12-month intervals, Conley (

6) found that depressed patients were significantly more likely than those without depression to use relapse-related mental health services. Also, Olfson and colleagues (

7) assessed clinical predictors of early rehospitalization among 262 patients with schizophrenia three months after discharge and found early readmission to be significantly associated with major depressive symptoms. Consistently, negative symptoms have also been associated with a worse course of schizophrenia and a higher rate of relapse, which our results confirm. Leifker and colleagues (

8) have shown that blunted affect and passive-apathetic social withdrawal accounted for all of the variance in predicting social outcome among 194 outpatients with schizophrenia.

The fact that we found that patients whose symptoms were in remission at discharge were significantly less likely to experience a relapse than those whose symptoms were not in remission is not surprising, because one would strongly expect that a patient with greater improvement during the acute treatment phase would have a more favorable course of illness (

9). Several studies have demonstrated that early and adequate symptom control is the precondition of achieving a favorable long-term course of the illness. Lambert and colleagues (

10), for example, followed over three years 392 patients with schizophrenia who had never received treatment and found that remission within the first three months after baseline as the strongest predictor of subsequent remission. Also, Wobrock and colleagues (

11) found that nonremission of symptoms after two weeks of treatment was a significant predictor of not achieving remission after three months of treatment.

In our study side effects at discharge were a significant predictor of relapse in both prediction models. Chabungbam and colleagues (

12) examined sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with relapse among patients with schizophrenia and found that those who experienced a relapse were significantly more likely to complain of moderate to severe side effects of medication. A possible explanation offered by the authors was that patients with more severe side effects may be those receiving a higher dosage of antipsychotics to combat relapse. In regard to antipsychotic treatment, we found that patients treated with first-generation antipsychotics at discharge were more likely to have a relapse during follow-up, which is supported by research data (

3).

Like other researchers who have assessed relapse predictors, we found that a worse attitude toward adherence at discharge was a significant predictor; this is believed to be one of the most reliable predictors of relapse in schizophrenia research. In a study of 477 patients with schizophrenia, Laan and colleagues (

13) found that 160 patients relapsed within six months of hospital discharge. The authors found that the relapse risk was substantially lower when a patient was properly adherent to the antipsychotic therapy that was prescribed during inpatient treatment. We also found that having a job at discharge was protective against relapse during follow-up. The association between employment status and relapse has been previously noted. In an analysis of three years of data for 6,516 patients with schizophrenia, Haro and colleagues (

14) found that social functioning, as measured primarily by having paid employment, was one of the most important predictors of the course of illness. The authors concluded that the association between paid employment and a more favorable course was due not only to the positive influence of work itself but also to other factors such as social support and patient competencies. This finding is somewhat in line with our finding that independent living status at discharge was protective against relapse.

A strength of this study is the inclusion of treatment outcome at hospital discharge in the prediction model, which also applied standardized definitions of outcome. Also, the naturalistic study design is closer to a real-world setting than a randomized controlled trial. However, the naturalistic design lacked sufficient control for the effect of pharmacological treatments. Rehospitalization was included in the definition of relapse, but rehospitalization may not reflect exacerbation of the illness, which should be considered in interpreting these results. In addition, the study was conducted in a single European country, and the generalizability of the results may thus be limited. Another limitation is that substance abuse, a well-known factor in relapse, could not be examined because patients with comorbid substance use disorders were not included in the study.

Conclusions

In this study, 52% of patients with schizophrenia experienced a relapse within the first year of hospital discharge. Patients without a job, with a higher HAMD-17 score, more medication side effects, and a poorer attitude about treatment at the time of discharge were more likely to have a relapse during the year after discharge. Therefore, providers should develop strategies to enhance adherence and diminish side effects before patients are discharged from the hospital. Helping patients maintain employment after discharge should also be considered in treatment approaches.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study was performed within the framework of the German Research Network on Schizophrenia, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research BMBF (grant 01 GI 0233).

The authors report no competing interests.