Compared with persons in the general population, individuals with serious mental illness are at greater risk of arrest for virtually every type of crime (

1). In the United States, as many as 15% of male and 31% of female jail inmates (

2) and an estimated 15%–20% of prisoners have serious mental illness (

3). Such high rates of involvement in the criminal justice system are of concern to policy makers, clinicians, and advocates alike, in part because mental health treatment in correctional settings is often inadequate (

4) and because having a criminal record can restrict access to housing, employment, and other domains necessary to achieve recovery (

5).

Persons with bipolar disorder, in particular, are more than twice as likely as the general population to commit violent crimes (

6) and nearly five times as likely to be arrested, jailed, or convicted of an offense other than drunk driving (

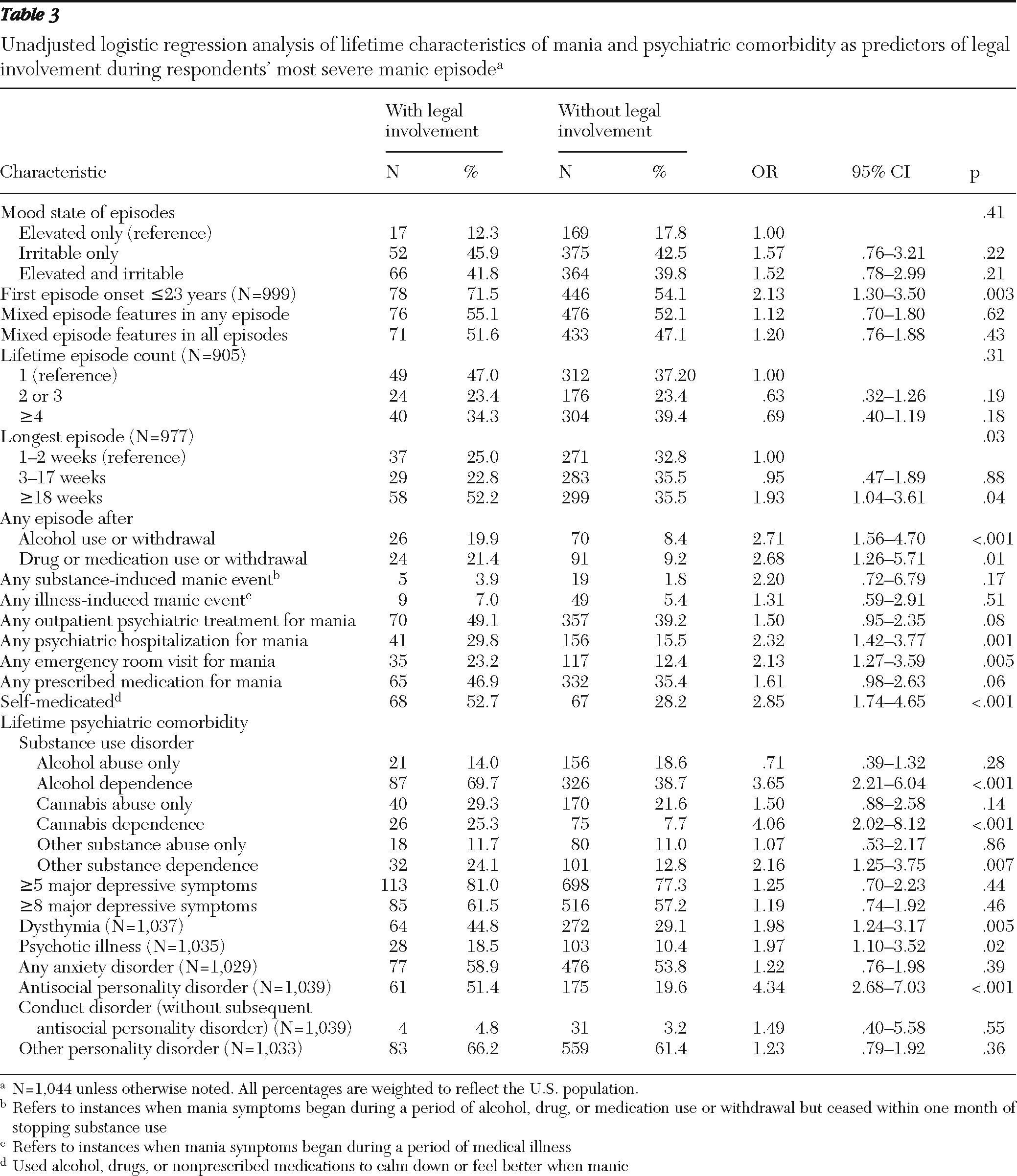

7). Those with co-occurring substance use disorders are eight times more likely than those bipolar disorder alone to have prior criminal justice problems (

8) and are six times more likely than the general population to have committed a violent crime (

6). Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) suggest that the incidence of violence (not necessarily resulting in justice involvement) among persons with bipolar disorder is significantly higher than in the general population only for those with a co-occurring substance use disorder (

9).

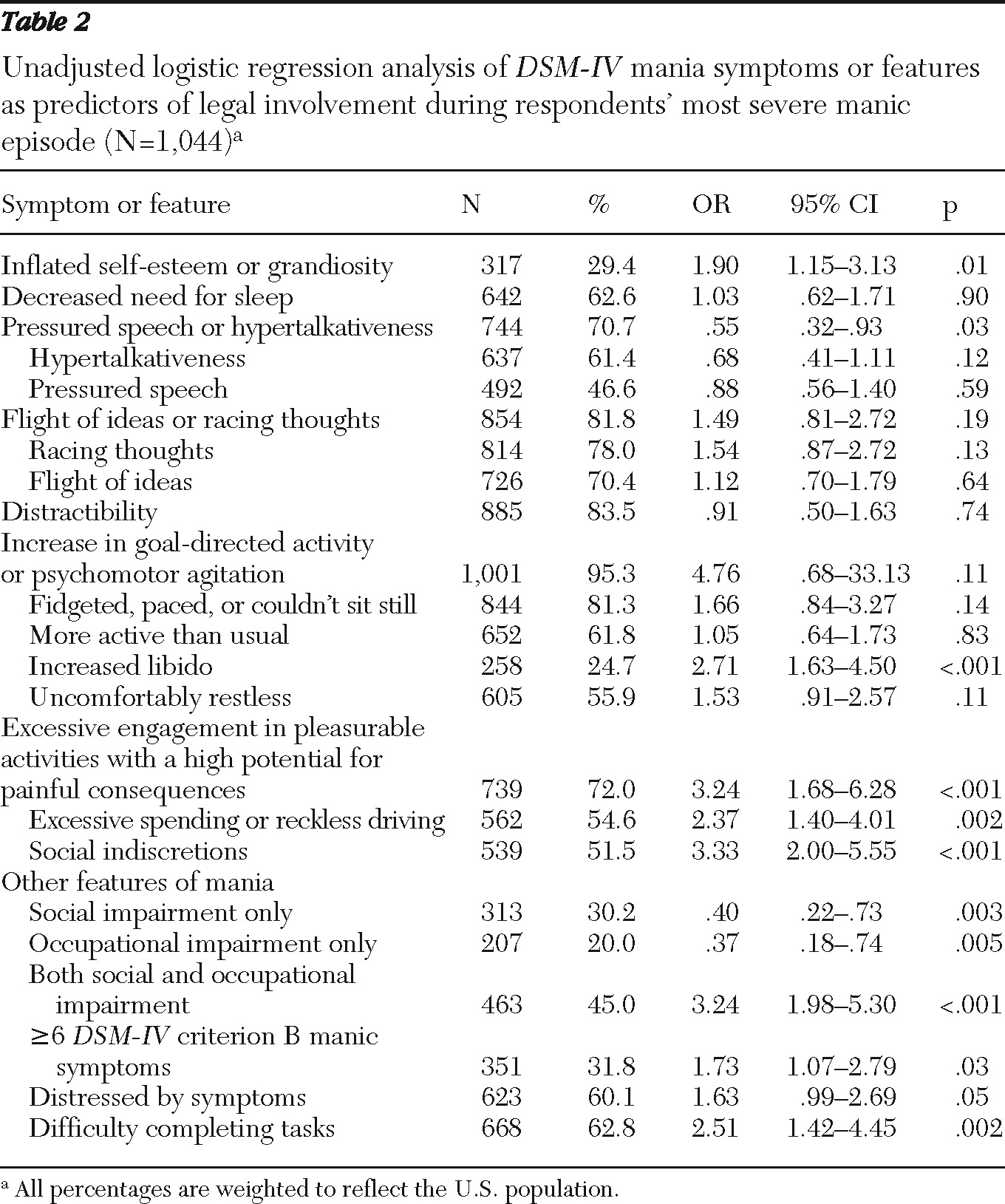

Intuitively, a number of symptoms of mania (for example, grandiosity and excessive engagement in risky activities) suggest that persons with bipolar disorder may be more likely to engage in criminal behaviors during this phase of their illness than in other phases (

10). Indeed, one study found that among correctional inmates with bipolar disorder, most (74%) reported being in a manic or mixed state when arrested (

11), and more frequent manic episodes and psychiatric hospitalizations have been shown to predict much of the lifetime risk of arrest among persons with bipolar disorder (

12,

13). In a recent study nearly 16% of inpatients hospitalized for mania engaged in criminal behavior during a seven- to 12-year follow-up period (

14,

15). Furthermore, violent or aggressive behavior by inpatients with bipolar disorder was found to be greater among those with grandiosity, impulsivity, and psychosis (

16) and during manic episodes with accompanying psychosis (

17) and hostile-suspiciousness (

18). Among adults who committed criminal offenses, including those with nonviolent charges, grandiosity (

19) and hypersexuality (

20) were found to be significant features of mania. On the other hand, one study found that patients with bipolar disorder were no more likely to commit violent crimes during manic episodes than during depressive episodes or during psychotic episodes than during nonpsychotic episodes (

6).

Methods

Sample

Data for this study were obtained from the NESARC, the largest U.S. epidemiologic survey to assess psychiatric disorders according to the

DSM-IV criteria. The NESARC assessed the same respondents with in-person interviews in two waves: wave 1, 2001–2002, and wave 2, 2004–2005 (

23,

24). The sample was representative of the U.S. adult (18 years and older), noninstitutionalized, civilian population, including the District of Columbia and all 50 states. Residents in noninstitutional group quarters (for example, boarding houses, dormitories, and shelters) were included, as were military personnel living off base (

23). Prisons, jails, and hospitals were not sampled. The sample was weighted to represent the U.S. population and adjusted for nonresponse. The study reported here used wave 1 data (N=43,093), the overall response rate for which was 81% (

25). Because this analysis of deidentified NESARC data did not involve direct interaction with human subjects, it was deemed exempt from review by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The NESARC used the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS) (

26), a structured diagnostic interview, to generate

DSM-IV diagnoses (

27) for major axis I and axis II (personality) disorders.

To define our cohort of individuals meeting DSM-IV criteria for a manic episode, we used responses from the manic episode section of the AUDADIS. Criterion A required endorsement of either a week or more of “extremely excited, elated or hyper mood” that caused others concern or that they thought was uncharacteristic of the respondent or a week or more of irritable mood.

Criterion B symptoms were assessed relative only to the episode during which the respondent's mood was the most elevated or irritable (referred to here as “most severe episode”). Consistent with

DSM-IV we required endorsement of three or more criterion B symptoms for those endorsing elevated mood and at least four symptoms for those only endorsing irritable mood. Because the AUDADIS does not systematically assess for mixed episodes, criterion C was not applied. However, we included mixed-episode features: having experienced at least a week of mood alternating between elevated and depressed-anhedonic for any (or all) manic episodes. [A table listing AUDADIS questions and the related criterion B symptoms is available in an online appendix at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

AUDADIS uses five questions to assess social and occupational impairment (criterion D) relative to the most severe episode: whether the respondent was uncomfortable or upset by his or her symptoms (distressed); had any serious problems getting along with other people (social impairment); had any serious problems with responsibilities such as working, doing schoolwork, or caring for home or family (occupational impairment); had trouble getting things done (difficulty completing tasks); and had any legal trouble, such as being arrested, held at the police station, or put in jail (legal involvement). Consistent with DSM-IV, for this study criterion D was met by the endorsement of either social or occupational impairment as described above or the endorsement of hospitalization for any lifetime manic episode. To be excluded under criterion E, all lifetime manic episodes had to be substance- or illness-induced. Episodes were illness-induced if a health professional told the respondent that all manic events were related to a medical condition or illness. Respondents who were told that any, but not all, manic episodes were related to a medical condition were coded as “any manic events illness-induced.” To fail criterion E for substance use (alcohol, medication, or drug) a respondent would need to report that all episodes followed substance use or withdrawal, report stopping substance use or not experiencing withdrawal symptoms for at least a month, and report that manic symptoms did not continue after the cessation of substance use or withdrawal symptoms for all episodes. Respondents who endorsed substance-induced episodes for some but not all manic episodes were identified as “any manic events substance-induced.” In summary, our cohort included respondents who met DSM-IV manic episode criteria A, B, D, and E as described above and for whom information about legal involvement was available.

Other variables

Mania-related variables included age at onset of first manic episode, number of lifetime manic episodes (separated by more than two months of normal mood), duration of longest manic episode, and onset of any mania after increased use of or withdrawal from alcohol, a medication, or a drug. Service use variables included ever having seen a mental health professional for mania, ever having been to an emergency room for mania, and ever having been prescribed medication for mania. “Self-medicated” was defined as having used alcohol, drugs, or nonprescribed medicines to calm down or feel better when manic.

Other lifetime clinical variables included alcohol, cannabis, or other substance abuse or dependence (opioids, methamphetamine, cocaine, hallucinogens, or another illicit drug or a prescription drug), psychotic illness or episode (diagnosed by health professional), dysthymia, any anxiety disorder (agoraphobia, panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder), antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder (without subsequent antisocial personality disorder) and other personality disorders (paranoid, schizoid, avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, and histrionic). Lifetime severity of DSM-IV major depressive episode symptoms was captured with two count indicators (five or more and eight or more symptoms).

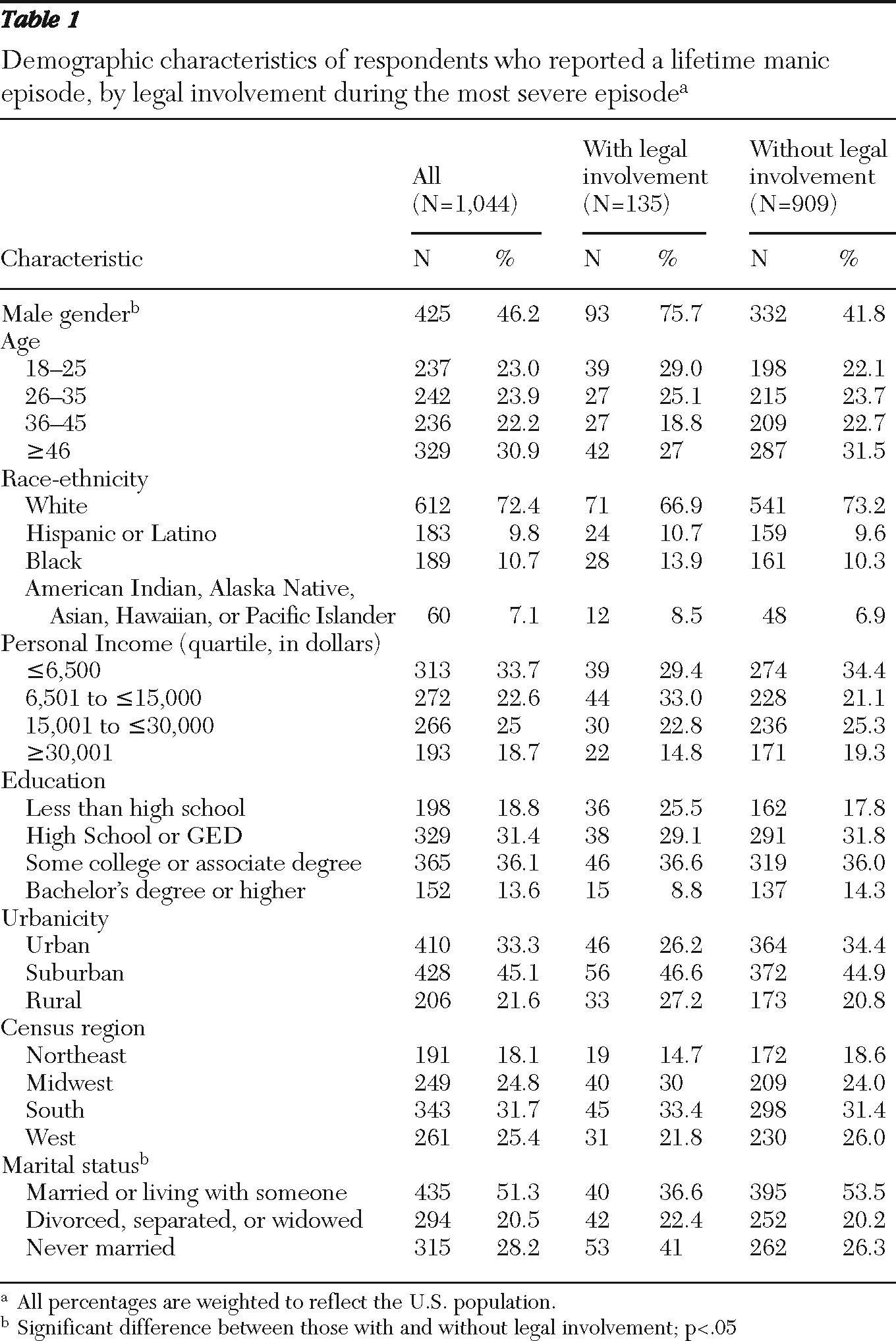

Demographic variables included gender, age, race and ethnicity, personal income, education, urbanicity, census region, and marital status.

Primary outcome

Legal involvement (from the criterion D question set on social and occupational impairment described above) was defined as being arrested, held at the police station, or put in jail, during the manic episode that the respondent identified as the most severe in his or her lifetime.

Statistical analyses

Design effects and subpopulation selection considerations in standard error estimation were addressed with Stata's “svy, subpop” procedure. Taylor series linearization method was used for standard error estimation with strata with a single primary sampling unit being centered at the overall mean. All estimates are weighted, and all confidence intervals account for the design effects and the subpopulation nature of our cohort. Bivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association of legal involvement with all variables. A multivariate logistic regression model of risk of arrest was constructed and included episode-specific symptoms and static factors present on or before the incident manic episode (gender, race, and age of first manic episode onset). Stata, version 10.1, was used for all analyses (

28).

Discussion

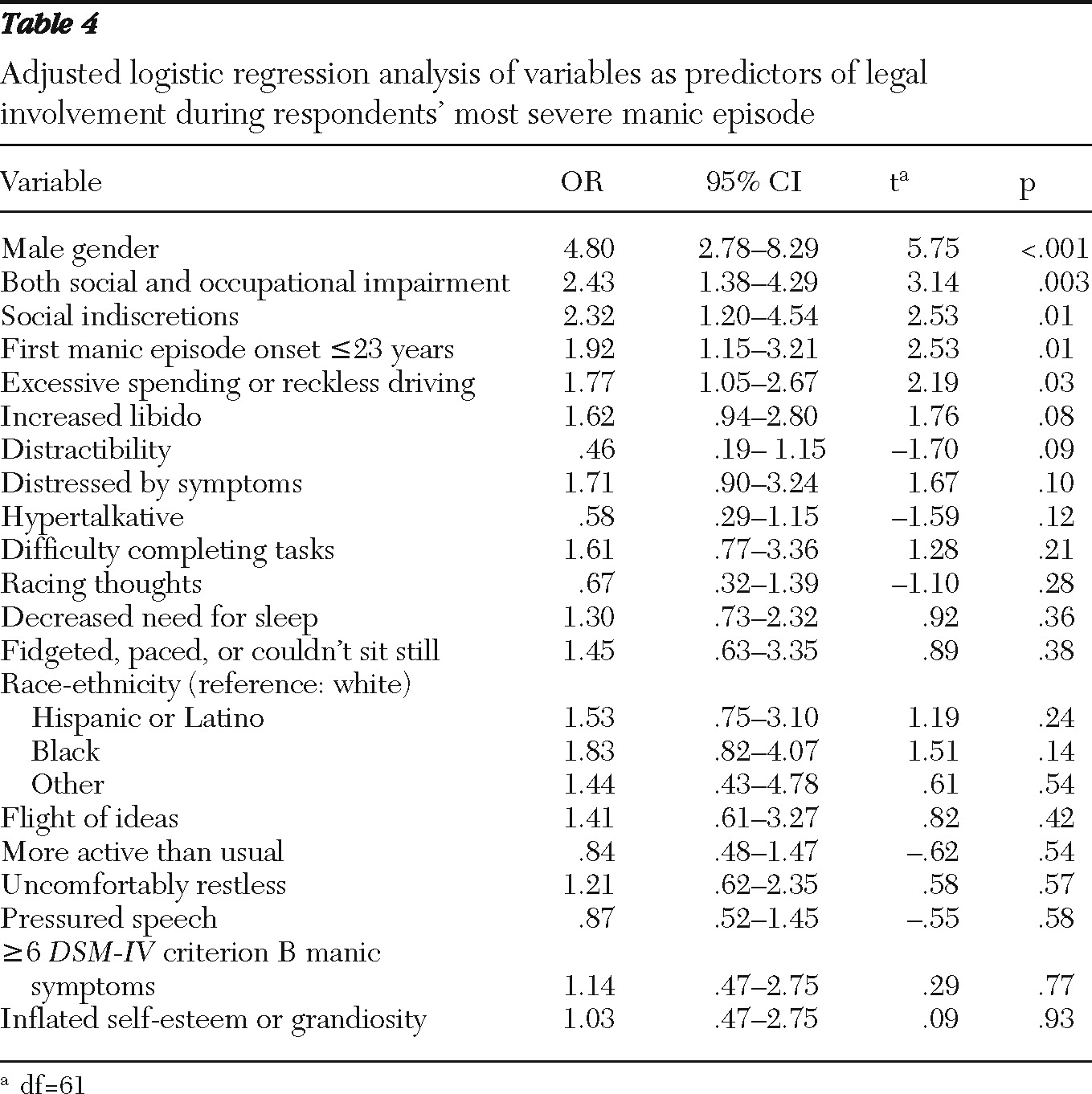

This analysis of wave 1 NESARC data represents, to our knowledge, the first large-scale community study to report the prevalence of involvement in the criminal justice system during severe manic episodes and its association with specific manic symptoms. The findings suggest that a relatively large proportion of individuals report legal involvement during their most severe manic episode (13.0%). The findings also offer a clinical framework in which to evaluate a person's risk for involvement with the criminal justice system by the presence of specific manic symptoms in addition to other lifetime risk factors.

Before the clinical and public policy implications of this research are considered, these findings need to be framed in the context of a number of limitations. First, the exclusion of persons residing in prisons, jails, and hospitals may have decreased the proportion of persons in the sample with bipolar disorder who experienced legal involvement during mania. The exclusion of persons in correctional settings is particularly problematic because it is unclear whether behaviors serious enough to result in such confinement have the same symptomologic precursors as those that do not lead to confinement. Because this group was excluded, the percentage of individuals experiencing legal involvement during a serious manic episode may have been even higher than the findings indicate. Second, although the outcome measure was specific and was uniformly applied to the study sample, there were no follow-up questions on the extent of further involvement with the criminal justice system. We do not know, for example, whether these (or other) manic symptoms predict criminal charges, incarceration, or a pattern of recurrent criminal justice involvement. Nevertheless, the extent of legal involvement clearly went beyond what might be considered nuisance police contact (that is, being stopped or interrogated). Because these respondents were arrested and possibly jailed during severe manic episodes, access to timely and effective psychiatric treatment may have been reduced at precisely the time when it was most needed. Third, legal involvement was assessed only with regard to the most severe manic episode; it is not known whether symptoms associated with less severe manic episodes are similarly predictive of arrest and detention. Fourth, respondents' recall may have been inaccurate at times, particularly with regard to events that occurred during manic episodes.

Other limitations derive from the cross-sectional nature of the wave 1 data. The unknown temporal relationship between the most severe manic episode and other lifetime characteristics, including age at the time of the index episode, marital status, educational level, and other critical traits prevented the use of these factors in predictive or other multivariate models (

29). The same was true for comorbid behavioral health conditions, such as substance use disorders, which are associated with arrest and which, for many respondents, were present at some point in their lives (

6,

8,

13).

Notwithstanding these limitations, use of the NESARC data brings a number of strengths to this study. The large size, diversity of socioeconomic status, and nationally representative nature of the sample support the generalizability of these results. Strict application of DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder and exclusion of alternative explanations for manic symptoms (for example, substance use and medical illness) also support diagnostic validity in this sample.

Criminal justice involvement among individuals with bipolar disorder remains an important policy and public safety concern. These findings accord with other large population-based studies that have shown that persons with bipolar disorder have a high risk of criminal justice involvement or violent behavior (

6,

7,

9) and reinforce the notion that this risk may be especially high during the manic phase of bipolar disorder compared with other phases (

11). Whereas other work has focused exclusively on violent behavior (

6) or particular types of crime (

7), these findings represent the broad spectrum of offenses for which individuals face booking and detention during severe mania. These data also support the long-held axiom of clinical wisdom, namely, that certain symptoms of mania predispose patients to criminal justice problems. These episode-specific associations held true even when the analysis controlled for selected lifetime risk factors.

The implications of these findings for addressing the criminal justice involvement of persons with bipolar disorder are noteworthy. With regard to clinical management and risk assessment, these data support providers in moving beyond the state-specific realm (that is, mania) to focus on a subset of patients whose risk appears to be increased by the presence of particular symptoms that are readily identifiable in clinical settings.

Although it is natural to focus on effects that achieve statistical significance at the p=.05 level, some of the odds ratios found in this study are substantial in size but have confidence intervals that include 1 and are thus not “significant” in the conventional sense. For example, an increase in libido was associated with a 62% increase in risk of legal involvement (p=.08), a factor that may have clinical, if not statistical, significance. Likewise, distractibility more than halved the risk of criminal justice involvement (p=.09), a factor that also might be of interest among clinicians attempting to evaluate an individual's risk of various outcomes during an escalating episode of mania.

Of course, to take advantage of these findings, providers need the opportunity to evaluate patients in clinical settings. As our analyses suggest, these high-risk patients as a group are more likely than those who do not experience legal involvement during severe mania to receive treatment for mania in outpatient, emergency room, and hospital settings at some point in their life. Unfortunately, we do not know whether these treatment encounters occurred before, during, or after the manic episode during which the person became involved with the criminal justice system. Nevertheless, the fact that these individuals eventually present for care provides an opportunity for clinical intervention and possible prevention of future criminal justice problems. Such preventive measures would be strengthened by understanding the extent to which particular sets or clusters of manic symptoms work synergistically to produce behaviors leading to legal problems and the relationship between other risk factors for criminal justice involvement and episode-specific symptoms of mania. These are important areas for future study.