Barriers to mental health care for military personnel and veterans have been examined extensively, and a number of factors that interfere with treatment seeking have been identified (

3). Several studies have examined barriers to care among Iraq and Afghanistan military personnel and veterans by using the Perceived Stigma and Barriers to Care for Psychological Problems (PSBCPP) (

3,

4), but no studies have examined whether such barriers interfere with prospective mental health treatment use (

3). The study reported here examined barriers to mental health care identified by use of the PSBCPP (

4,

5) and their association with prospective VA mental health care use among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who sought VA care and who endorsed mental health symptoms.

Methods

The sample was drawn from Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who were assessed between May 2005 and August 2009 (N=479) at intake to a VA postdeployment health clinic offering general medical, mental health, and social work assessment and referral services. Mental health evaluations were encouraged for all veterans seeking care, and an assessment packet was administered to each patient at intake. Veterans with missing data on all items about perceived barriers (N=28) or on health care utilization (N=31) were excluded, as were those from the Coast Guard (N=2) and Air Force (N=18) and those who did not endorse mental health problems (N=95), yielding a sample of 305 veterans.

Data on race-ethnicity were missing for more than 5% of veterans (N=28, 9%). There was no association between missing data and demographic characteristics. The VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, Seattle Division, Institutional Review Board approved this study and a waiver of consent.

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race-ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, employment status, annual household income, and military branch. The sample of 305 veterans included those who endorsed depressive symptoms in the two weeks before the assessment (N=273), which was indicated by a score of ≥5 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (

6); those who endorsed at least subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the past month (N=231), as indicated by a score of ≥35 on the PTSD Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M) (

7,

8); or those who endorsed current or past-six-month alcohol misuse (N=91), as indicated by a score of ≥1 on the PHQ-9 alcohol abuse subscale.

A modified statement from the PSBCPP (

4,

5) was included. For ten potential barriers, veterans were asked to rate their agreement with the statement “If you had any post-deployment mental health concerns, what factors might affect your decision to receive mental health counseling or services?” (1, strongly disagree; 3, neither agree nor disagree; and 5, strongly agree). The ten barriers were related to access, stigma, and trust. Access-related barriers were “I don't know where to get help” (N=58, 19%, rated the item as ≥4), “I don't have adequate transportation” (N=31, 10%), “It is difficult to schedule an appointment” (N=61, 20%), and “There would be difficulty getting time off work for treatment” (N=101, 33%). Stigma-related barriers were “It would harm my career” (N=84, 28%), “Members of my unit might have less confidence in me” (N=79, 26%), “My unit leadership might treat me differently” (N=95, 32%), and “I would be seen as weak” (N=110, 37%). Trust-related barriers were “My visit would not remain confidential” (N=50, 17%), and “I do not trust mental health professionals” (N=27, 9%).

Item responses within each barrier domain were averaged to create access, stigma, and trust subscales; internal consistency was acceptable or higher (Cronbach's α=.649, .886, and .709, respectively).

The outcome was a dichotomous measure reflecting use of outpatient mental health care in a mental health setting (for example, at a PTSD or mental health specialty clinic) or in a primary care setting in VA Northwest Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN 20) medical centers and community-based clinics one year after intake. Use was documented with administrative data from the VISN 20 Data Warehouse (

9). The average number of visits for the 305 veterans in the year after intake was 7.5±14.3, and veterans who had at least nine visits (N=75, 25%) were considered to have received minimally adequate treatment, on the basis of methods used in a national study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans receiving care from the VA (

2).

Analyses were performed in SPSS, version 16.0. Logistic regressions included all variables associated with the outcome in bivariate tests (p<.05). Because of multicollinearity, mental health symptom indicators were examined in separate models.

Results

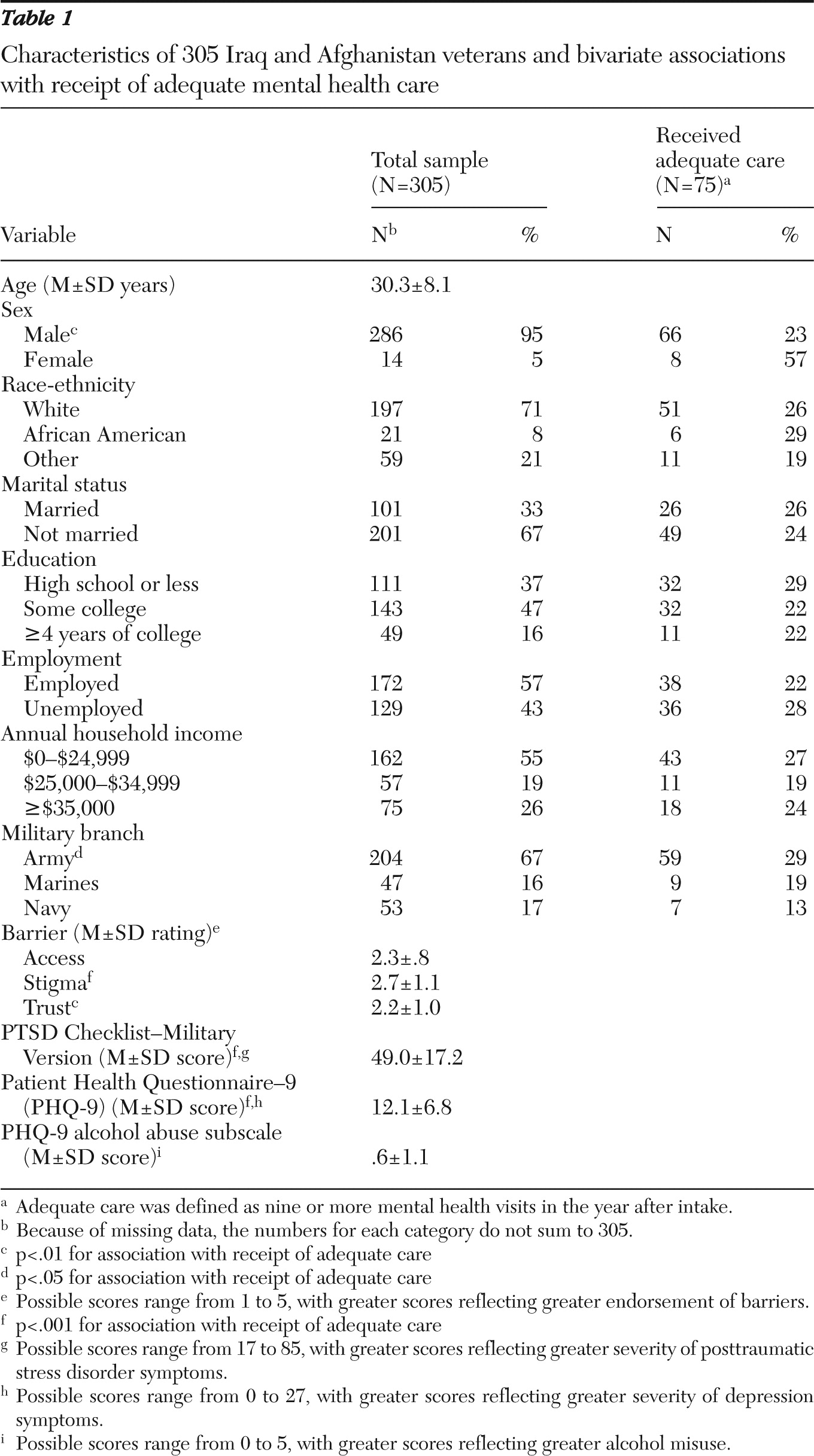

Table 1 summarizes data on sample characteristics. A majority of participants were male, Caucasian, unmarried, and employed, had an annual income of less than $25,000, and had served in the Army. Nearly half had some college education. Stigma-related barriers were the most commonly endorsed (111 veterans, 37%, endorsed at least one stigma-related barrier).

In bivariate tests, sex and military branch were significantly associated with use of mental health care (

Table 1). Those with at least nine mental health visits had significantly more severe PTSD symptoms than those with fewer than nine visits (mean±SD PCL-M score of 56.2±16.1 versus 46.6±16.9). Those with at least nine visits also had significantly higher depression symptom severity (mean PHQ-9 score of 14.7±6.9 versus 11.2± 6.5) and had higher levels of endorsement of stigma-related barriers (mean rating of 3.0±1.1 versus 2.6±1.1) and trust-related barriers (mean rating of 2.5±1.0 versus 2.1±1.0).

When PTSD symptom severity, sex, military branch, endorsement of stigma-related barriers, and endorsement of trust-related barriers were entered into the model, women were significantly more likely than men to have received adequate mental health treatment (odds ratio [OR]=4.82, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.37–16.99, p=.014). PTSD symptom severity also was associated with increased likelihood of having received adequate mental health treatment (OR=1.03, CI=1.01–1.05, p=.003). When depression symptom severity replaced PTSD in the model, women (OR=3.98, CI=1.17–13.49, p=.027) and those with greater depression symptom severity (OR=1.06, CI=1.01–1.11, p=.01) were significantly more likely to have received adequate mental health treatment. Receipt of adequate treatment was not associated with endorsement of stigma-related barriers or trust-related barriers.

Discussion

This study is the first to prospectively examine the association between barriers to mental health treatment seeking that were identified by the PSBCPP and use of mental health care among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Although perceived barriers among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are well documented (

3), it does not appear that the barriers measured in this study interfered with receipt of adequate treatment among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans seeking VA care. Other factors were independently associated with the receipt of adequate care. Severity of PTSD and depression symptoms were predictors of mental health care utilization. Male veterans were less likely than female veterans to have received adequate mental health treatment and were therefore at risk for unmet need. Only 25% of veterans received adequate treatment, which is comparable to rates found in a national study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans (

2) and which suggests that other critical factors may be at play.

Several limitations of this study warrant mention. The study measured barriers to care among treatment-seeking veterans, and the findings may not generalize to veterans who do not seek VA care. Future studies should examine whether the measured barriers have an impact on receipt of treatment from non-VA providers and on VA treatment initiation. The association of these barriers with treatment use may vary if use is measured as a count variable rather than as a dichotomous measure of receipt of adequate treatment. However, barriers were not associated with treatment use in the analyses reported here when the outcome was treated as continuous (data not shown).

The PSBCPP was developed for active-duty personnel, and the questions that elicit the respondent's view of the perceptions of unit members or leaders may have different relevance for veterans separated from service. Nonetheless, the sample's high endorsement of these items suggests that former peers and military leadership remained a salient reference group. We did not assess all potential barriers. For example, distance to VA facilities is a known barrier to mental health treatment in this population (

2) and should be included in future studies that examine the association between barriers and treatment seeking. The PSBCPP emphasizes public stigma, whereas self-stigma is also likely to influence treatment seeking; future studies should incorporate additional measures to capture a broader range of potential stigma-related barriers (

3).