Despite increased use of services in the United States, most people with mental disorders still do not receive treatment (

1). It is especially important to address the lack of treatment among adolescents and young adults because providing early treatment can help prevent the progression of mental illness and its adverse consequences.

Help seeking and service use by young people are influenced by a wide array of factors at an individual, social, and health-system level. Attitudes and knowledge are thought to be among the most important individual factors that influence help seeking (

2,

3). The use of mental health treatment by young people has increased substantially in recent years (

4), indicating, perhaps, that attitudes and knowledge about mental illness among young people may be improving. The key factors that influence help-seeking behavior in this population may be shifting. This study takes an initial step toward examining that possibility by estimating the extent to which negative attitudes and beliefs about treatment were present in a national sample of college students with untreated mental health problems.

Methods

Data included pooled samples from students at 26 colleges and universities included in the 2007 and 2009 Healthy Minds Study (

5), a national online survey of mental health and help seeking among college students. A random sample of at least 1,000 students from each campus (N=33,379) was invited to complete the survey. A total of 13,105 students completed the survey, for a completion rate of 39%. The sample included 8,487 females (65%) and 4,618 males (35%); 9,156 (70%) were undergraduates, and 3,949 (30%) were graduate students. A majority (N=8,152, 62%) were age 18 to 22; a total of 3,482 (27%) were age 23 to 30, and 1,471 (11%) were age 31 or older. Most (N=8,804, 67%) were non-Hispanic white, 1,437 (11%) were Asian, 802 (6%) were Hispanic, 692 (5%) were black, 604 (5%) were of multiple races or ethnicities, and 766 (6%) were of other races. To adjust for potential sample bias related to survey nonresponse, sample probability weights were constructed by using administrative data, including gender, age, race-ethnicity, and grade point average, available for the initial random sample.

Informed consent was obtained from participants, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards at all campuses.

Three mental health problems were examined: current symptoms of major depression or anxiety and past-year suicidal ideation. Major depression was defined as a positive screen by using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (

6). Anxiety was defined as a positive screen for either generalized anxiety or panic disorder by using the PHQ. The criteria for depression or anxiety were limited to students with functional impairment: reporting that depressive symptoms in the PHQ-9 made it at least “somewhat difficult” to “work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people,” or reporting that emotional or mental difficulties affected academic performance in the past four weeks. Past-year suicidal ideation was measured by using a question adapted from the National Comorbidity Survey (“In the past year did you seriously think about committing suicide?”) (

7). Individuals were considered to have an untreated mental health problem if they screened positive for any problem but reported that they did not use psychiatric medication or receive counseling or therapy in the past year.

The analysis focused on three factors known to be highly correlated with mental health service use among students (

8,

9) and general samples (

10–

12): stigma, beliefs about treatment effectiveness, and perceived need for help. Financial factors were not examined because free or very low-cost services were available at all campuses, and survey results indicated that financial constraints were not commonly reported as barriers (

5).

Stigma was measured by responses on a 5-point scale to three statements about attitudes toward people who use mental health treatment. High stigma was defined as a mean personal stigma score at or above the midpoint (2.5), indicating that the respondent was at least as likely to agree as to disagree with stigmatizing statements (

13). Questioning treatment effectiveness was defined by responses to two questions about the helpfulness of medication and therapy or counseling, respectively, for depression. Possible responses range from “not at all helpful” to “quite helpful.” The responses “not at all helpful” and “a little helpful” were considered to indicate a questioning belief about treatment effectiveness. A lack of perceived need was indicated by answering no to the question, “In the past 12 months, did you need help for emotional or mental health problems such as feeling sad, blue, anxious, or nervous?” Barriers to service use were assessed with a survey question asking, “In the past 12 months, which of the following [26 choices] explain why you have not received medication or therapy for your mental or emotional health?”

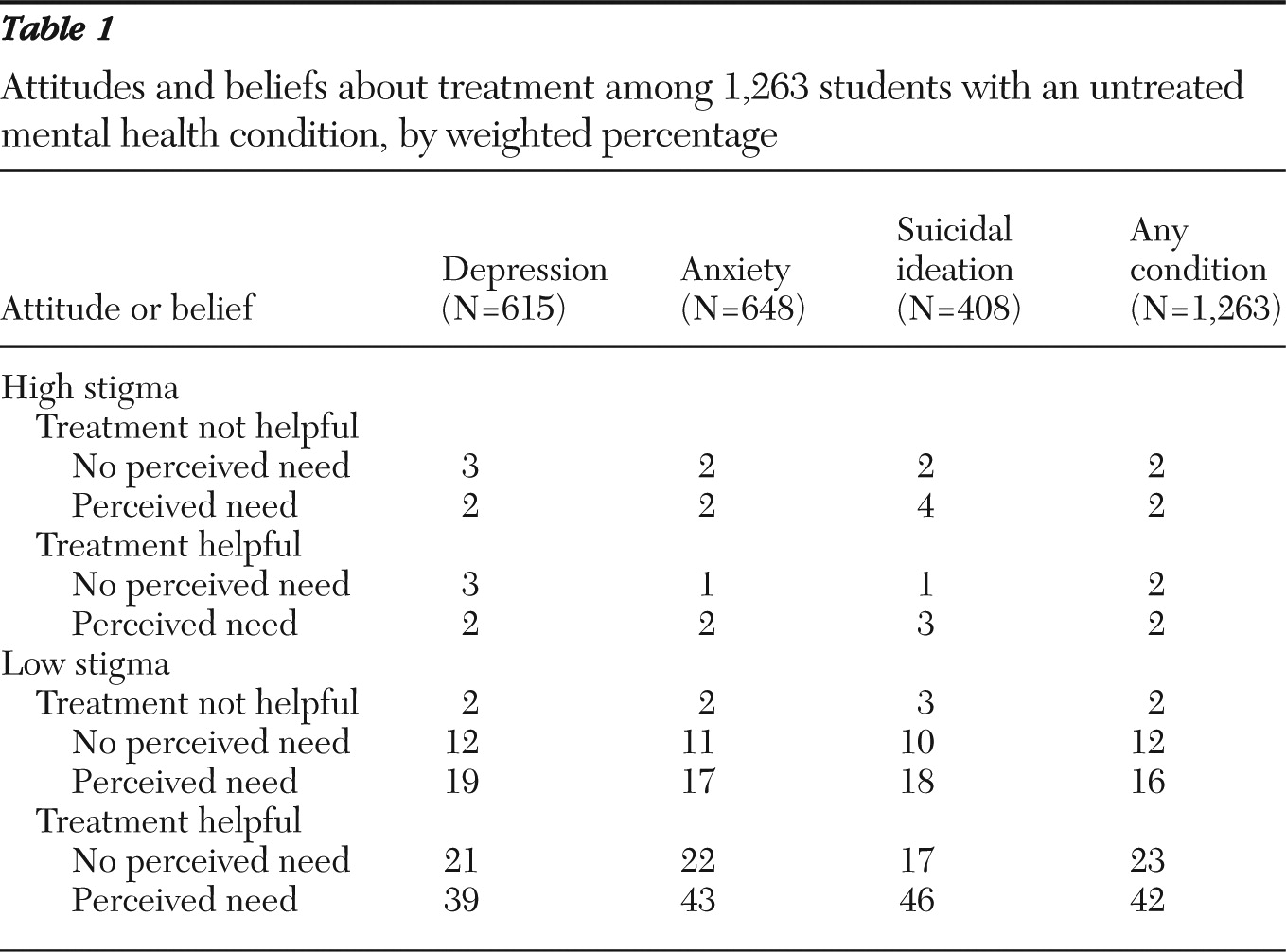

The analysis calculated the weighted percentage of persons with untreated mental health problems who fell into eight distinct groups that were based on combinations of the three binary factors described above. The analysis also calculated the most commonly selected responses among the 26 choices to the question about why the respondents did not receive services.

Results

A total of 2,350 survey participants (18%) met the criteria for at least one mental health problem (depression, anxiety, or suicidal ideation). The analysis focused on the 1,263 persons (54%) within that group who reported no treatment in the past year.

Table 1 shows the weighted percentage of students in each group, defined by apparent barriers. The distributions of attitudes and beliefs were almost identical for each mental health condition. Overall, a majority (65%) of untreated students reported low stigma and positive beliefs about treatment, including 42% who perceived a need for help and 23% who did not. Among the students who reported low stigma and positive beliefs about treatment, the reasons for not receiving treatment endorsed most commonly were, “I prefer to deal with these issues on my own” (55%), “I don't have time” (51%), “Stress is normal in college/graduate school” (51%), and “I question how serious my needs are” (47%).

Discussion

Most college students with untreated depression, anxiety, or suicidal ideation reported positive attitudes and beliefs about treatment. Many of these students appeared to view treatment as acceptable and helpful, but not urgent or essential. They questioned the seriousness of their issues, preferred to handle the issues themselves, believed that their distress was a normal part of the college experience, or reported not having time for mental health services.

These data suggested that for many young people in recent cohorts, help seeking and service use for mental health may be analogous in some ways to pursuing a nutritious diet and exercise; these behaviors are commonly viewed as healthy and are associated with little stigma, but many people fail to engage in them (

14). People's behaviors do not seem to be rationally consistent with the preferences and information they appear to have. In such situations, behavioral economics research has shown, people may respond to subtle interventions that reframe the decision or make it easier to commit to a healthy choice. For example, reframing the default option has had a large impact on a range of health behaviors (

15); for mental health services, that might take the form of introducing regular, automatically scheduled emotional wellness check-ups that allow students to opt out.

The evidence in this study should be regarded as tentative; the analysis had clear limitations, including the modest survey response rate, the brevity of measures, and the focus on a limited number of potential determinants of help seeking. Also, the findings may be quite different, particularly in terms of financial barriers, for young people who do not attend college.

Conclusions

The data in this exploratory study challenge the traditional focus on attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge as central determinants of help seeking for mental health problems. The findings provide initial evidence that research and practice addressing help seeking may need to be supplemented with new approaches. It may be especially useful to adapt lessons learned from addressing other areas of health, such as diet and physical activity, in which unhealthy behaviors persist despite positive attitudes, beliefs, and intentions. Additional research is needed to explore these possibilities more carefully.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for data collection was provided by the Virginia Department of Health; the Children, Youth, and Family Consortium at Pennsylvania State University; and colleges and universities that participated in the study. The Healthy Minds Study was developed originally with funding from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation and the University of Michigan Comprehensive Depression Center. Support for Dr. Hunt has been provided in part by the Arkansas Biosciences Institute, the major research component of the Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Proceeds Act of 2000, and by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) South Central Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the VA. The authors thank Scott Crawford, M.A., Sara O'Brien, B.A., and their colleagues at Survey Sciences Group, L.L.C., for implementation of the survey data collection and local study coordinators for valuable assistance at each participating institution.

The authors report no competing interests.