In this study we examined two hypotheses. First, IPS improves both the rate of obtaining employment (job acquisition) and the amount of work (job duration, hours worked per week, and total hours and wages). Second, employment outcomes within domains are strongly correlated, whereas outcomes across domains are relatively weakly related.

Results

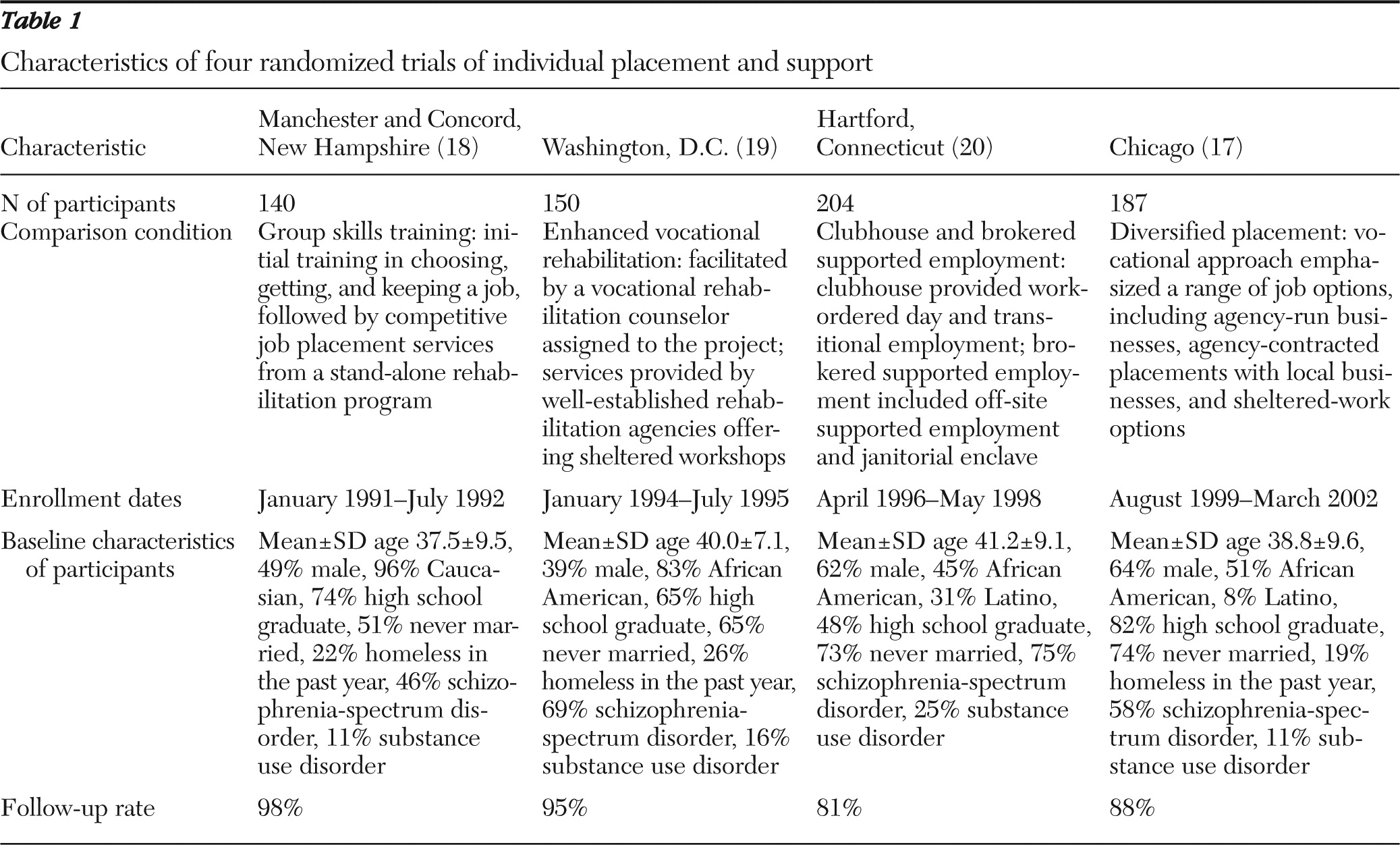

Characteristics of the total sample—IPS participants and participants in the control sample—have been reported in detail elsewhere (

24). The mean±SD age for the total sample was 39.5±9.0 years; 55% (N=372) were men; 39% were white (N=265), 46% were African American (N=311), and 13% were Latino (N=85). Thirty-four percent (N=229) had less than a high school education, and 81% (N=546) were receiving Social Security disability benefits. In terms of diagnosis, 63% (N=429) had a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, and 34% (N=229) had a diagnosis of a mood disorder. With a few very minor exceptions, the IPS and control samples were similar on baseline characteristics.

The worker subsample consisted of 216 IPS participants and 91 participants in the control sample. Comparisons on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in the worker subsample yielded two significant differences. Workers in the control sample had worked more weeks in paid community jobs during the past five years than IPS workers (93.12±83.59 compared with 61.12±69.46; t=3.21, df=305, p<.01, d=‒.43) and had received less in Social Security benefits during the past month ($402.84±$356.38 compared with $527.20±$343.31; t=‒2.85, df=301, p<.01, d=‒.36).

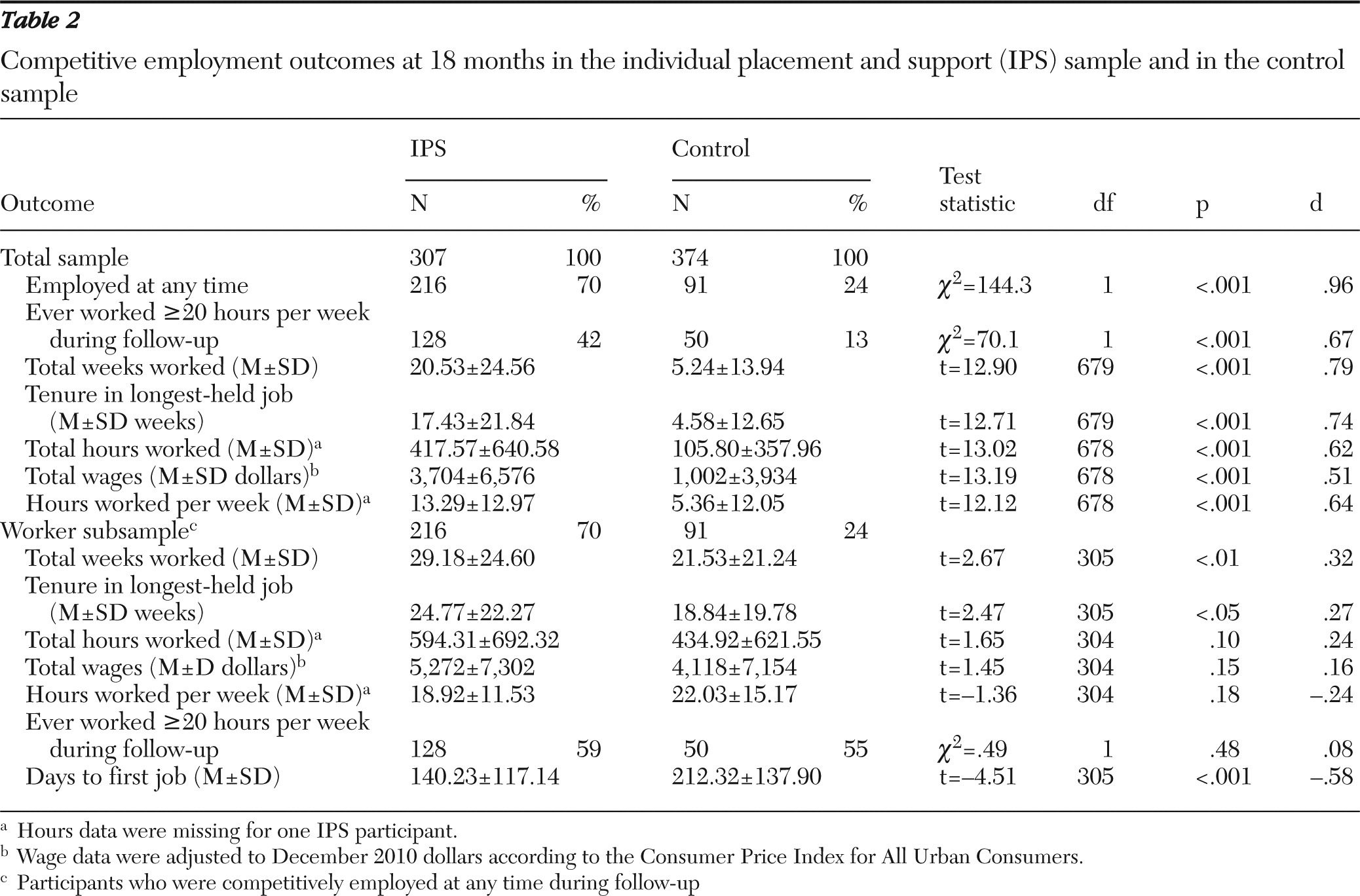

As shown in

Table 2, in the total sample, IPS participants had significantly better outcomes than the participants in the control sample on all seven competitive employment measures, with effect sizes ranging from .51 to .96. Analyses of the worker subsamples revealed three significant differences favoring IPS over the control programs. Working clients in IPS started their first jobs sooner, averaged more weeks worked during follow-up, and had longer job tenure at their longest-held job compared with workers in the control programs. Among IPS workers, 105 (49%) held one job, 62 (29%) held two jobs, and 49 (23%) held more than two jobs, whereas among workers in the control sample, 58 (64%) held one job, 18 (20%) held two jobs, and 15 (17%) held more than two jobs (

χ2=5.90, df=2, N=307, p=.05). The differences in the worker subsamples on other competitive employment outcomes were not significant. Overall, the large differences between the IPS and control samples prompted us to examine correlations between employment outcomes for each group separately.

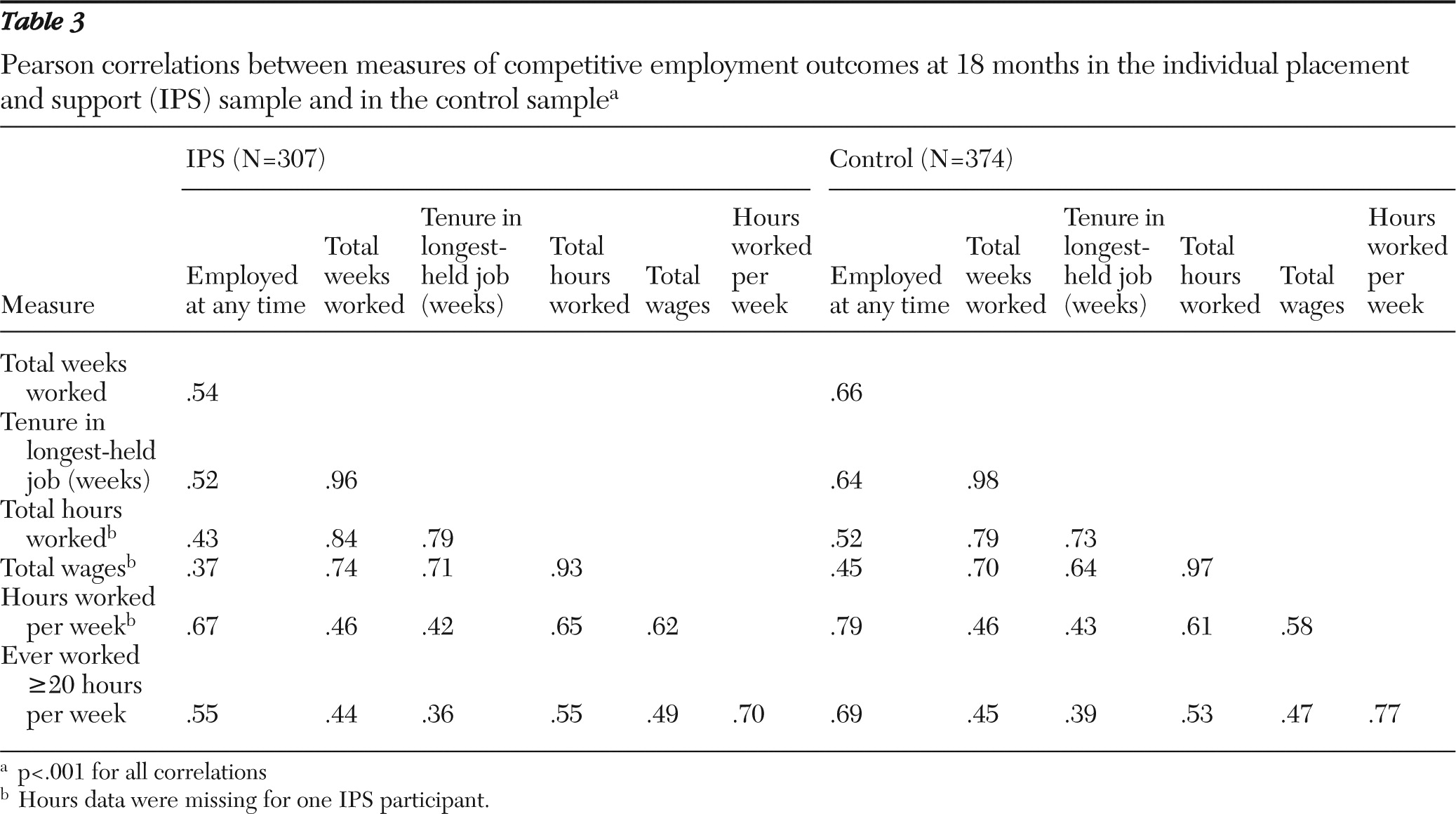

Table 3 shows the correlations between the competitive employment outcomes in the total IPS and control samples. Most of the correlations were large, statistically significant, and in the predicted direction. The strongest associations were between total weeks worked and job tenure in the longest-held job and between total hours and total wages. The pattern of results was similar for the IPS sample and the control sample.

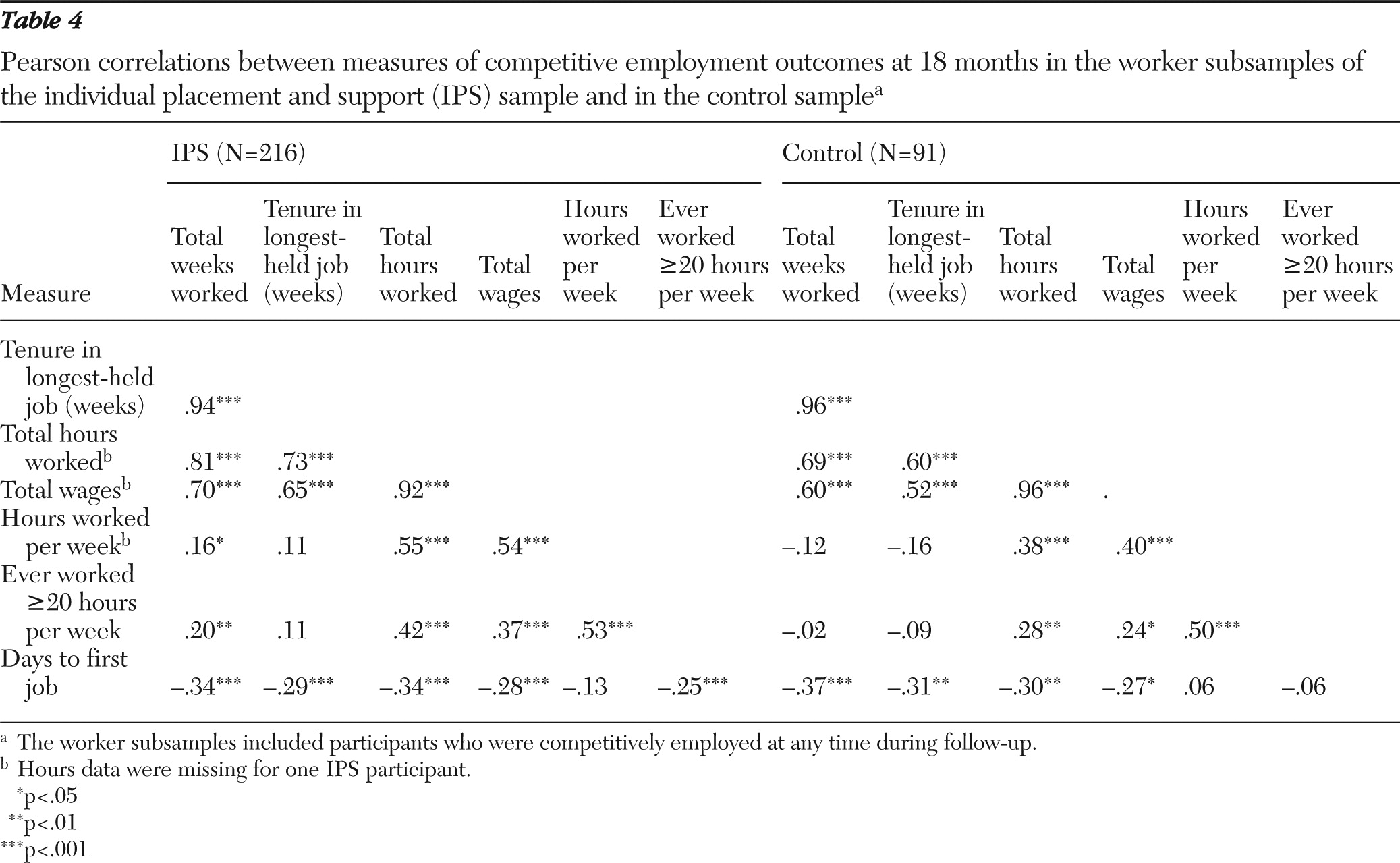

Table 4 shows the correlations between the outcomes for the worker subsamples. The majority of these correlations were also significant.

Discussion

Our analyses strongly supported the first hypothesis: IPS outperformed control programs in all domains of employment outcome: acquisition, duration, hours worked per week, and total hours and wages. Even the analyses restricted to the worker subsamples showed significant advantages for IPS on three of seven outcome measures. The latter findings are remarkable because the comparisons between IPS workers and workers in the control programs were nonequivalent because of adverse selection, with significantly better work histories for control program participants. Thus IPS was superior to the other vocational models on all domains of competitive employment outcome, not just job acquisition.

Our analyses only partially supported the second hypothesis: relationships within vocational domains were generally strong, while those between domains were mixed. Within domains, measures were mostly highly correlated because of closely related operational definitions. Many of the cross-domain correlations were also strong, such as between the job duration domain and the domain of total hours and wages. In short-term follow-up studies, strong correlations are expected between measures such as total weeks worked and job tenure in the longest-held job, but the expected degree of association is less obvious in longer-term follow-up studies.

One important finding not previously reported in the literature is that the simple (and widely reported) measure of job acquisition (competitive employment rate) is a decent proxy for other employment measures assessing job duration, hours worked per week, and total hours and total wages, with correlations ranging from .37 to .79. In terms of interpreting research reports, the competitive employment rate statistic (that is, the percentage of participants who gain competitive job during follow-up) has been rightly criticized as a crude indicator. But the findings reported here suggest that although employment rate is an imperfect measure, it is useful as a general-purpose measure of employment outcome. This finding is practical and useful because the employment rate is often the easiest outcome to obtain and the sole measure used for quality improvement purposes (

25). At a practice level, this also means that one critically important element in the process of helping clients achieve their goal of working is getting that first job. This by no means obviates the importance of job matching, ongoing support, and other elements of the employment process, but certainly job acquisition is a necessary condition for long-term employment.

This study also demonstrated that the principle of rapid job search is consistent with job duration, as suggested by significant negative correlations between days to first job and total weeks worked and job tenure in longest-held job. The findings contradict the assumption made by one early theoretical formulation of supported employment, the choose-get-keep model, which theorized that clients with severe mental illness required an extended period of career planning before starting the job search (

26). According to this theory, the preliminary period of career planning would reap later benefits by facilitating longer job tenure once a client found a job suiting his or her career aspirations. This model (and theory) has been disconfirmed (

27). The findings of this study further support the view that job search should not be delayed by skills training or other preparatory activities. No current evidence indicates that delaying the job search enhances job tenure. Moreover, a larger proportion of IPS sample than the control sample held multiple jobs during follow-up, suggesting a commitment by IPS programs to providing greater opportunities for clients to become attached to the work force. The findings validate the IPS principle of giving second chances to clients whose initial job ends.

Also illuminating were findings in the worker samples regarding measures that were at best weakly correlated. For example, correlations between the two job duration measures (job tenure and tenure in longest-held job) and hours worked per week were small, ranging from .16 to ‒.16, suggesting statistical independence between these two domains. We interpret these findings as suggesting that individuals' preference for working a certain number of hours per week—or their capacity to do so—may differ from their willingness or ability to stay in a particular job over time. This lack of association between job duration and hours worked per week suggests that people work in the amounts that meet their goals to feel productive, contributory, and in control, not necessarily to maximize income. For some, this is five hours per week; for others, it is 20 hours or more per week. In this study, the decision about the number of hours to work was not always limited by fears of losing benefits because many individuals worked well below that level. This interpretation accords with self-reports in long-term follow-up studies (

28).

Generally, relationships between measures within employment domains are very strong because the measures often address closely related concepts, especially in short-term follow-up studies. For example, in studies with short follow-up periods, the longest-held job largely determines the total duration of employment, and hours of work determine wages, because most clients work in entry-level jobs with a relatively narrow range of wages.

For economic analyses of employment outcomes that combine findings across studies, the strong association between hours worked and total earnings suggests a convenient analytic strategy. Specifically, economists could aggregate findings across multiple studies by using the proxy measure of hours worked and subsequently converting the results to their approximate dollar equivalent. This technique may permit researchers to combine findings across studies conducted in different time periods and in different communities (or nations) and may permit inferences about earnings from employment that might circumvent some imputation challenges related to discounting, cost of living, minimum wage, and the like. Estimation strategies that minimize the assumptions, especially additive assumptions, may be both more transparent and more conservative.

We have no way of estimating how many part-time workers would work full-time if benefits regulations were to change. Some have speculated that clients receiving Social Security Disability Insurance perceive an “earnings cliff” that may result in a loss of benefits if they exceed substantial gainful activity for more than an allotted number of months (

29). If this theory is correct, clients should avoid this eventuality by working up to, but not above, the earnings limit. In practice, however, relatively few clients seem to respond this way (

30).

Finally, this study suggests that many employment measures are moderately to highly correlated, but it does not obviate the need to define a standard core battery of measures for future vocational studies (

31). Such a battery is the single best way to ensure comparability across studies and to permit syntheses in meta-analyses.

We have proposed a conceptual framework for classifying employment measures. The fourfold framework is a beginning. A comprehensive framework would include many other domains. In addition, within each domain are many possible measures that were not examined in this study. For example, within the duration domain, rather than measuring weeks worked, an even more standardized measure of duration would be percentage of time worked (weeks worked divided by total weeks of follow-up). In this study, weeks worked and percentage of time worked yielded statistically equivalent results, but in analyses comparing data sets with variable follow-up periods, only the percentage measure is directly comparable (

4). The Rehabilitation Services Administration defines “successful closure” for clients within its system by using a measure that fits in the duration domain (

32). Another important measure of duration found in the IPS literature is the “steady worker” concept, defined as working at least 50% of the follow-up period (

33). Vocational researchers would benefit by incorporating not only economic concepts related to productivity, which includes both quantity and quality of work, but also components of lost productivity, such as absenteeism and presenteeism (

34). Vocational research should also routinely track clients working above substantial gainful activity.

Limitations of the findings reported here include the methodological shortcomings found in the original studies, which are related to relatively short follow-up, missing data, reliability of measurement, and other factors. As in other studies of IPS, we have focused exclusively on competitive employment. Future research might also examine noncompetitive employment outcomes. Type of occupation, as measured by the Standard Occupational Classification system (

www.bls.gov/soc), should also be examined. Measures of job quality (

35) are needed, as are measures of job satisfaction and other aspects of workers' experience.

Measuring job tenure in randomized controlled trials has been problematic because many participants are employed at the end of follow-up (that is, many job tenure periods are right-censored). Thus the literature consistently underestimates job tenure. The time between study enrollment and first day employed also limits job tenure because participants often spend the first few months of the study involved in engagement, job development, interviewing, and other activities. The optimal solution, of course, is to conduct long-term follow-up studies. In the absence of long-term follow-up, we propose weeks worked during follow-up as the single most valid measure of job duration (

33). Weeks worked ignores the issue of number of jobs held, consistent with the IPS principle of helping clients obtain a new job if an initial job is unsatisfactory or ends for any reason.

Finally, these analyses did not include measures of variability between IPS teams and between employment specialists. The job strategies pursued by various IPS teams may differ, yielding higher competitive employment rates but jobs of shorter duration for clients of some teams (

36).

Conclusions

We examined longitudinal competitive employment outcomes in a large database of clients with severe mental illness who were enrolled in IPS supported employment and other vocational services. Our analyses showed that IPS improves competitive employment outcomes in four domains: job acquisition, job duration, hours worked per week, and total hours and wages. Our findings also suggest that measures within these domains are strongly related, whereas measures are variably related between these domains. The correlational patterns suggest analytic and measurement strategies for use in future studies, especially in meta-analytic reviews in which proxy measures may be required.

Ideally, a unified conceptual framework that encompasses employment measures used in diverse fields of inquiry, including vocational rehabilitation, occupational therapy, longitudinal research, and economics, as well as measures used by federal agencies, such as the Department of Labor, the Rehabilitation Services Administration, and the Social Security Administration, would provide a common vocabulary and an opportunity to make meaningful comparisons across disciplines.