When an individual experiences a mental health crisis, Virginia Law Section 37.2-809 permits temporary detention for up to 48 hours, in addition to weekends and holidays, for evaluation and emergency treatment under a temporary detention order (TDO). Within 48 hours, authorities must hold a civil commitment hearing. The four possible hearing outcomes are dismissal of the commitment petition, mandatory outpatient treatment, voluntary hospitalization, or involuntary hospitalization.

Currently, Virginia is one of only three states to require a commitment hearing within 48 hours of initial detention. At the other extreme, three states allow up to 30 days for a hearing. Most states require a hearing within four to eight days. Not only is Virginia's 48-hour TDO period among the shortest in the nation, but commitment hearings often occur within 24 hours of the start of the detention (

1). A short detention period may not allow sufficient time to stabilize and evaluate individuals. Virginia is considering extending the 48-hour limit to 72 hours (

2), a scaled-back version of a recommendation to extend it to four or five days (

3). The longer period is expected to allow Community Service Boards (CSBs), which serve as the point of entry to publicly funded mental health, mental retardation, and substance abuse services, time for adequate evaluation and crisis stabilization, leading to lower rates of involuntary commitment (

2).

To determine whether longer TDO periods can reduce the need for involuntary commitment and its associated stigma and trauma, we utilized the natural variation in TDO length in Virginia. Although Virginia requires a hearing within 48 hours when possible, the length of the TDO period can extend up to five days if the detention falls during a holiday weekend. This natural variation provides an opportunity to compare the effect of different TDO lengths on hearing outcomes and subsequent hospitalization. The Virginia SupremeCourt's new Court Management Systems (CMS) database began tracking TDOs and hearing outcomes across the state in 2008. We combined CMS data with Medicaid data from hospitalization claims, which allowed us to match the length of a TDO and hearing outcome with the length of the subsequent hospital stay for a sample of Medicaid recipients.

Because of a lack of data, relatively little research has examined the effect of temporary detention on subsequent commitment outcomes. Virginia's Commission on Mental Health Law Reform studied commitment hearings during May 2007, assessing more than 1,500 civil commitment hearings (

4). Most civil commitment hearings (80%) resulted in inpatient hospitalization, whether voluntary or involuntary. A significant variation was found in TDO length across Virginia. It appeared that the variation resulted from differences in the types of information and personnel involved in the hearings and differing scheduling practices. However, there were insufficient data on subsequent hospitalizations to identify a link between TDOs and hospitalization length.

Barclay (

1) reviewed data from Virginia, Colorado, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania on lengths of stay in inpatient facilities before and after commitment hearings. She concluded that Virginia's short TDO period was generally considered inadequate for a thorough assessment of the individual. A longer TDO period allows patients to stabilize and, if necessary, detoxify and enables clinicians to make more accurate assessments. A longer TDO period thus increases the likelihood that a case will be dismissed at the hearing or that the patient will agree to voluntary hospitalization in lieu of commitment. TDOs that are too short may also increase the probability of an error in the decision-making process leading to the commitment hearing.

In the investigation of the April 16, 2007, shooting at Virginia Tech, the Inspector General for Mental Health, Mental Retardation and Substance Abuse Services found that the mental health examinations performed in connection with commitment hearings are often very brief and fail to capture potentially important information about an individual (

5). The study found that the short period from detention to commitment hearing “makes it very difficult, if not impossible, to collect and consider additional collateral information about the individual. This also makes it difficult to complete the physical exam and psychiatric evaluation, assessment and treatment plan before the commitment hearing is held” (

5). These findings have led some policy makers to consider the costs and benefits of extending the TDO period.

Although few studies have examined the relationship between temporary detention and civil commitment, researchers have looked at a range of factors that influence involuntary detention. Rosenfield (

6) analyzed characteristics of patients and found that nonwhite males were more likely to be involuntarily hospitalized. She argued that this finding was partly attributable to greater police involvement in the entry of nonwhites into treatment (

6).

Distribution of resources also influences commitment. Bruckner and colleagues (

7) examined involuntary civil commitments in California after an increase in funding for mental health services and found a decrease in 14-day commitments, but not in 72-hour holds, after the disbursement of funds. The increased funding enabled more individuals to be treated in the community. This is consistent with Bonnie and colleagues' (

8) finding that the need for coerced involuntary inpatient treatment may be reduced or avoided for most people in crisis if adequate community-based mental health services are in place to engage the person through case management to support treatment adherence. Alternatively, Engleman and colleagues (

9) looked at emergency evaluations in Virginia and found that in addition to the clinician's characteristics and the setting where the evaluation took place, significant predictors of detention were the clinician's knowledge of bed availability. In other words, the lack of resources resulted in fewer hospitalizations.

Methods

Data from the CMS database on commitment hearings for three quarters—from July 1, 2008, through March 31, 2009—were combined with Virginia's Medicaid claims files for individuals with a mental health diagnosis. The study was reviewed by the University of Virginia's institutional review board and received exempt status because all data were blind-coded and deidentified before being provided to the researchers. Data were analyzed using Stata, version 10, statistical software. The CMS database contained an entry for each hearing, regardless of whether it was at the beginning or end of the TDO. Anindividual's hearings were matched on the basis of the second hearing's having a later date than the TDO and the person's first name and birth date. This method was less likely to yield errors than matching by last name and birth date. It resulted in 9,005 matches. The CMS data were then matched to the Medicaid claims file with MySQL. Initially there were 5,497 observations. After exclusion of repeat entries for the same visit, care related to pharmacy, personal care, physician visits, and hospital outpatient care, 508 matches resulted. Because of data entry errors, we do not know the precise number of Medicaid matches. For example, we excluded 402 entries without an identification number and 180 without a CSB number, some of which may have been a match.

The Medicaid claims file provided information on the length of the hospitalization, if any, that immediately followed the commitment hearing, as well as information on the age, race, sex, and primary diagnosis of the Medicaid recipients. We excluded individuals with more than 21 days of hospitalization or two standard deviations above the mean (N=8). Many of these extended stays were by individuals who were hospitalized indefinitely, and the commitment hearings were held in order to renew their stay. However, excluding them did not significantly change the results. The final data set included a sample of Medicaid recipients (N=500) who had a mental health diagnosis and at least one TDO during the study period.

A logistic model was used to formally test whether longer TDOs were correlated with an increased probability of dismissal, including mandatory outpatient treatment, rather than hospitalization; and an increased probability of voluntary rather than involuntary hospitalization. A multivariate regression was then used to investigate the relationship between TDO length and the length of subsequent hospitalization. Covariates included the CSB serving the individual with the TDO, as well as the person's sex, age, and race. A dummy variable indicated whether the primary diagnosis from the Medicaid claims file involved a serious mental illness, which we defined as an ICD-9 diagnosis of schizophrenic disorder (ICD-9 code 295) (N=155) or affective psychosis (ICD-9 code 296) (N=232). TDO was treated as a continuous variable in the logistic regression and a categorical variable in the multivariate regression analysis.

Results

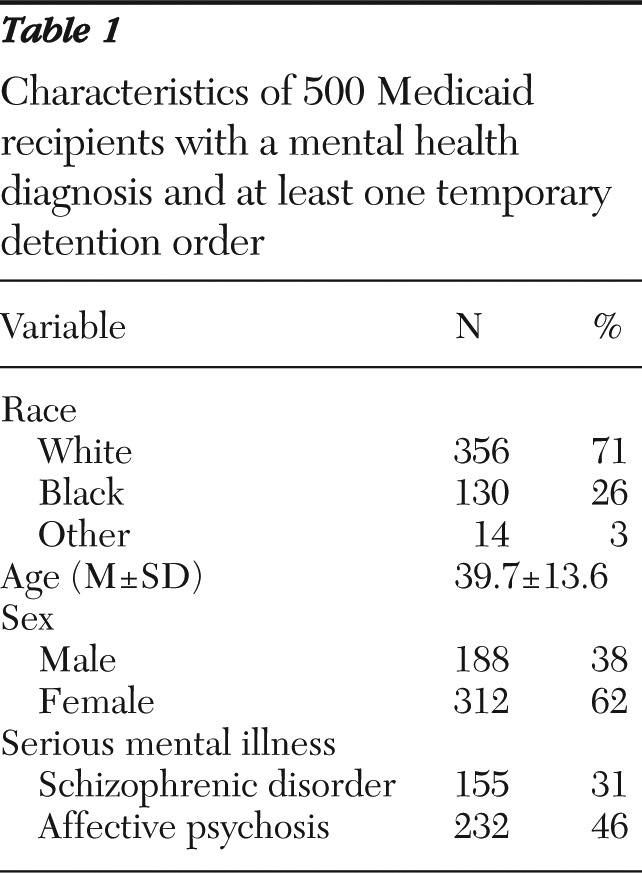

Table 1 presents data on the characteristics of the 500 persons in the sample. Race was categorized as white (71%), black (26%), or other (3%). The mean age was 39.7 years, and women made up more than half of the sample (62%). Thirty-one percent of the sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenic disorder, and 46% had a diagnosis of affective psychosis.

TDO length and civil commitment hearing outcome

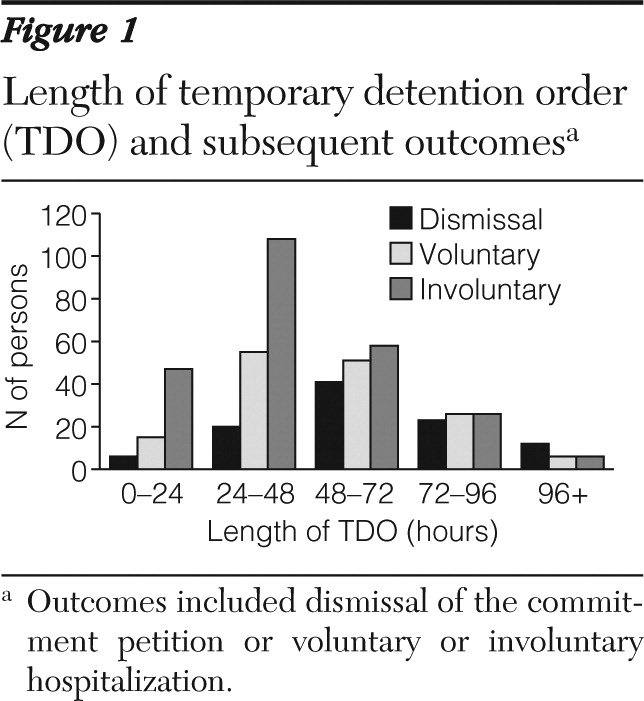

The first part of our analysis investigated the relationship between length of the TDO and the TDO hearing outcome (

Figure 1). A total of 245 individuals were involuntarily committed (49%), 153 agreed to voluntary hospitalization (31%), and in 102 cases (20%) the case was dismissed (N=99) or the person was assigned to mandatory outpatient treatment (N=3). In comparison, for the initial 9,005 observations in the CMS database, 56% had involuntary commitments, 26% had voluntary hospitalizations, and 18% had their cases dismissed.

The findings supported the expectation of a positive correlation between TDO length and the likelihood of dismissal (

Figure 1). Among individuals with a TDO of less than 24 hours, 69% were involuntarily committed and only 9% had their case dismissed. After a three-day TDO (72–96 hours), the percentages of dismissed cases, voluntary hospitalizations, and involuntary commitments were about equal. After a TDO of four or five days, 50% had dismissed cases and another 25% had voluntary hospitalizations.

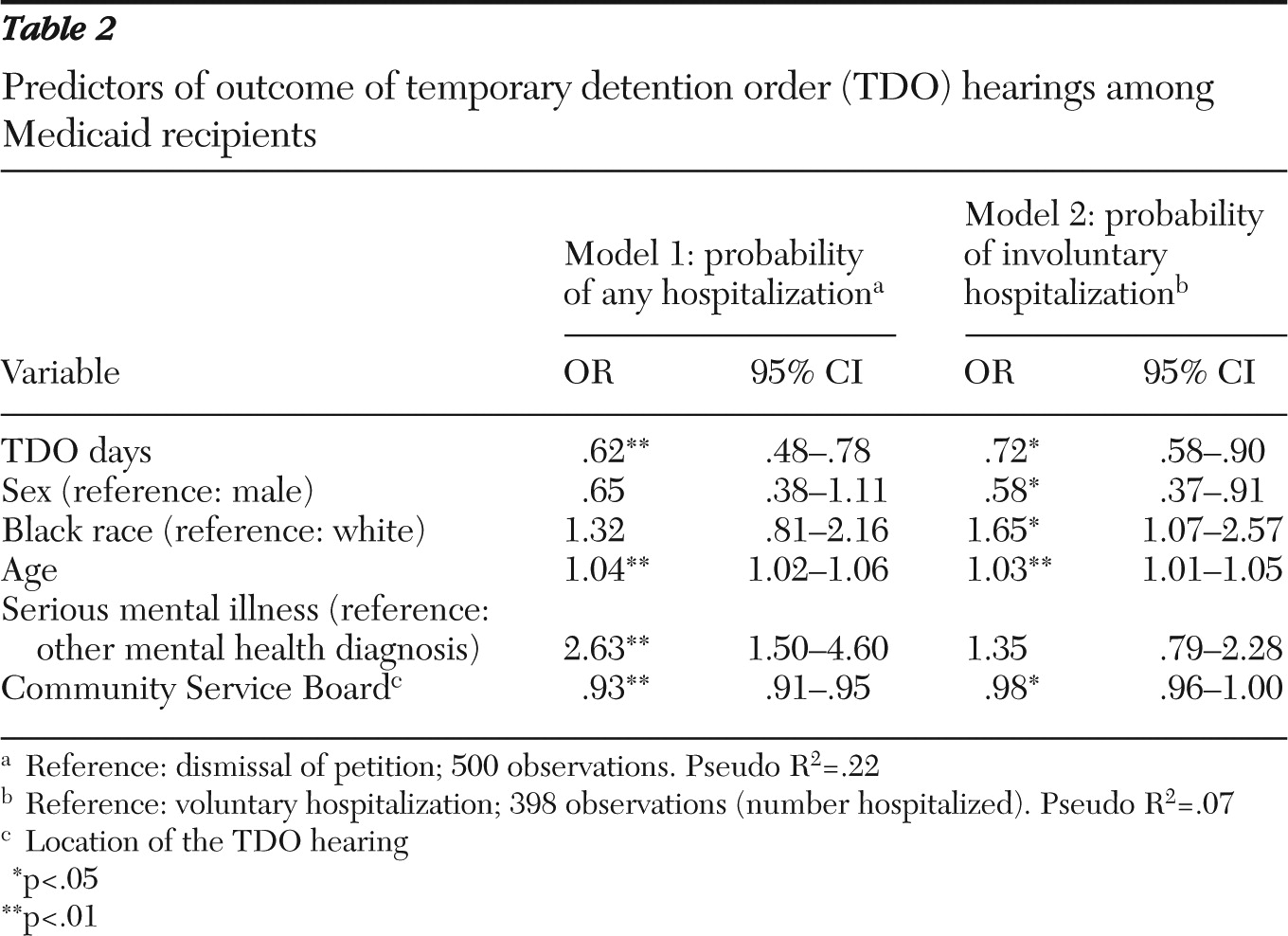

Results from the logistic regression showed that longer TDO periods were correlated with a lower probability of hospitalization.

Table 2 presents odds ratios (ORs) for dismissal versus hospitalization and for voluntary hospitalization versus involuntary commitment. For dismissal versus hospitalization, the OR of .62 indicates that a longer TDO period decreased the probability of any hospitalization and increased the probability of case dismissal. Furthermore, having a serious mental illness and being older increased the probability of hospitalization following a TDO of any length. The CSB location was also significant in predicting dismissal or hospitalization after the TDO period. The importance of CSB location is consistent with the previous findings that suggest that TDO length is determined primarily by the institutional structure of the CSB, rather than by a clinical decision in response to the health or mental state of the individual (

4). It is unclear why being older increased the likelihood of hospitalization and warrants further investigation in future research.

We also used logistic regression analysis to examine whether longer TDO periods were correlated with subsequent voluntary hospitalization (

Table 2). Only individuals who were hospitalized were included in the model (dismissals were excluded). In this model, a longer TDO decreased the probability of an involuntary commitment (OR=.72), as did age and CSB. Being black increased the probability of involuntary commitment. More research is needed to understand the role of age and race in civil commitment, but the result is consistent with Rosenfield's (

6) finding that nonwhite males are more likely to be involuntarily hospitalized partly due to greater police involvement with the entry into treatment. Having a serious mental illness was not a significant predictor, which may be due to the fact that most of the individuals (80%) who were hospitalized after the TDO period had a serious mental illness.

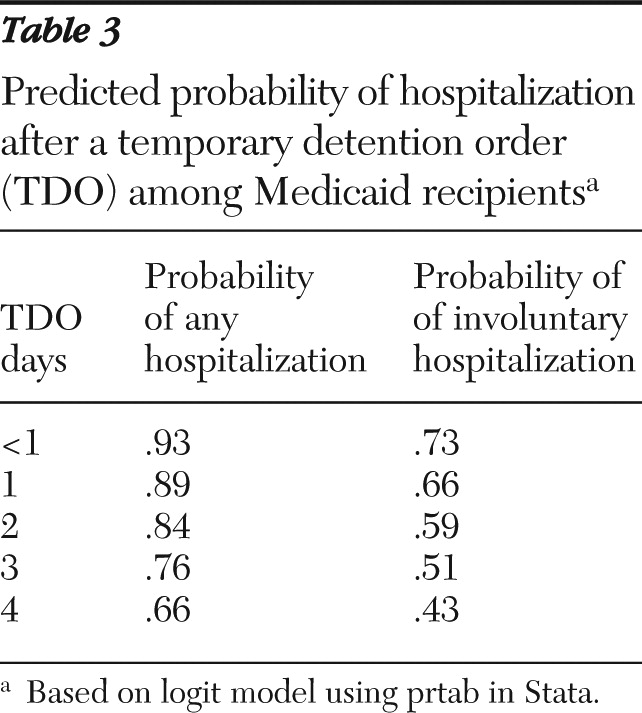

On the basis of the logistic regression coefficients, we also calculated the expected probability of hospitalization.

Table 3 presents predicted probabilities for various TDO lengths. The predicted probability of hospitalization decreased as TDO length increased. When the TDO period increased from two to three days (48 to 72 hours), as has been proposed in Virginia, the probability of subsequent hospitalization was reduced by .08, or 8%. When an individual was held less than 24 hours, the probability of involuntary commitment was 73%. After a four-day TDO, the probability of involuntary commitment dropped to 43%. The results indicate that increasing the TDO length from two to three days, as has been proposed, would decrease the probability of involuntary commitment from .59 to .51.

TDO length and length of hospital stay

The second part of our analysis focused on the association between length of TDO and length of subsequent hospitalization. The dependent variable, hospitalization days, was defined as the number of continuous days that an individual was hospitalized after the commitment hearing, from one to 21 days. Individuals with hospital stays of more than 21 days were excluded because TDO hearings are often a formality needed to extend long-term care. TDO length was treated as a categorical or dummy variable rather than as a continuous variable. The results should be interpreted as the importance of the specified number of TDO days relative to a TDO of less than 24 hours.

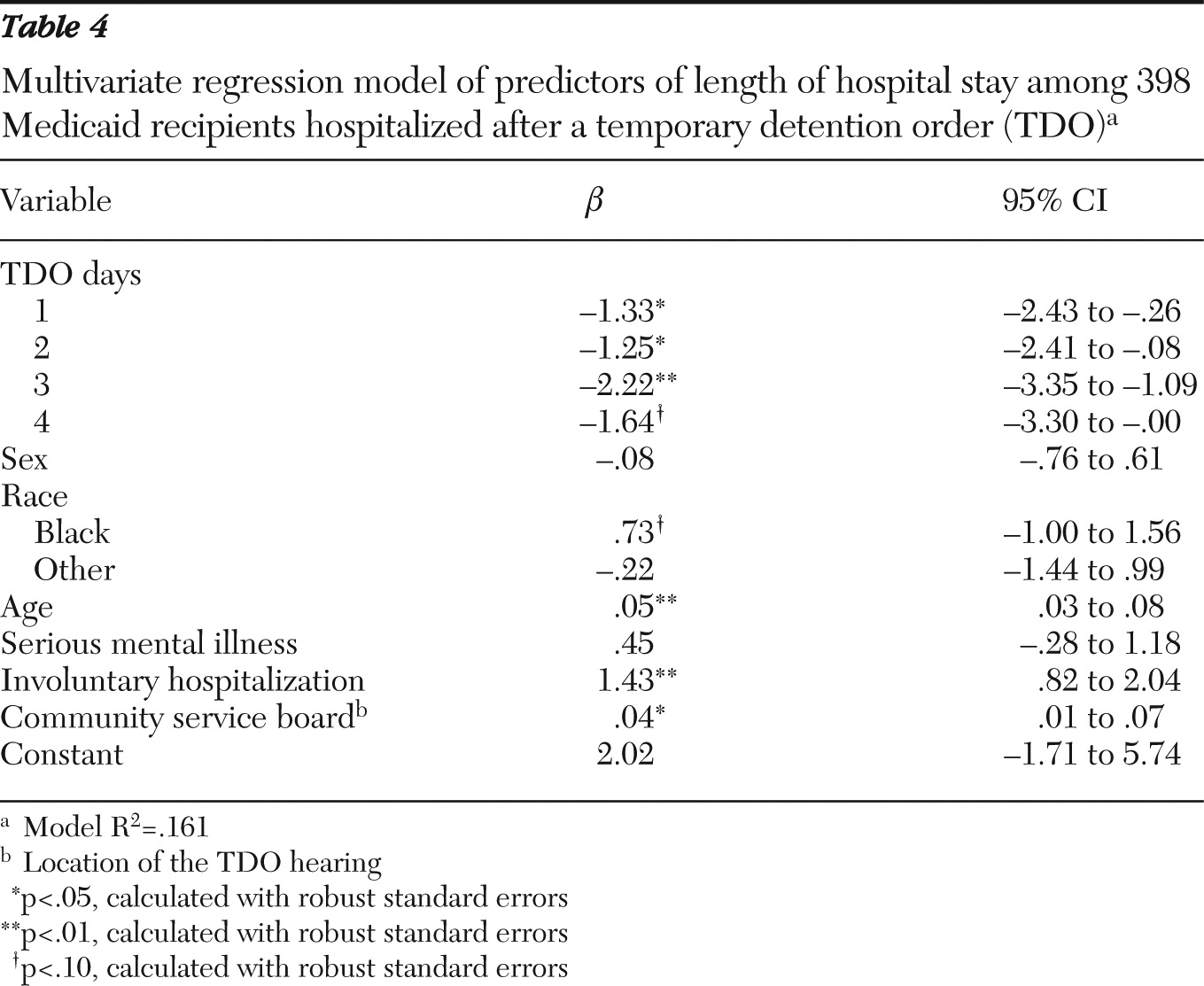

A multivariate regression model showed that fewer TDO days were correlated with longer subsequent hospitalizations (

Table 4). TDOs of all lengths were associated with a significant reduction in the length of subsequent hospitalization. However, total hospitalization time, including the TDO period and the post-TDO hospital stay, generally increased as TDO length increased. Increasing TDO length from less than one to two days was associated with a reduction in subsequent hospitalization of 1.25 days. Similarly, increasing TDO length from less than one to three days was associated with a reduction of 2.22 days of hospitalization. This finding suggests that increasing the TDO length from two to three days, as has been proposed in Virginia, would be correlated with a reduction in subsequent hospitalization of .97 days. The only net reduction in care time (TDO days plus post-TDO hospital days) occurred when the TDO length increased from less than one to one day, which reduced the subsequent hospital stay by more than one day (1.33 days).

Estimates for fiscal year 2010

To estimate the effect on overall days of detention and hospitalization, we first estimated the expected increase in days of detention under the longer TDO period (72 hours). We then determined the expected reduction in days of post-TDO hospitalization attributable to longer TDO periods. Reduced hospitalization included both the reduction in length of hospital stay and the reduction in the number of individuals hospitalized. Finally, we estimated the total number of additional days of detention that would have resulted in 2010 if the longer TDO period (72 hours) had been in effect.

According to the e-Magistrate database maintained by the Commonwealth of Virginia Supreme Court, a total of 20,927 adult TDOs were issued in fiscal 2010. If the 72-hour TDO period had been in effect, our findings suggest that Virginia could expect an increase of 26,288 TDO days and a decrease of 24,506 hospitalization days, resulting in a net increase of 1,782 treatment days. However, commitment hearings for many individuals occur less than 24 hours from the start of their TDO. To the extent that the state can encourage or require a minimum TDO length of more than 24 hours, we can expect a reduction in the cost of care for these individuals. Increasing TDO length from less than one day to one day would reduce the length of subsequent hospitalization, both voluntary and involuntary, by 1.4 days. Thus increasing the minimum TDO length may well offset the cost of an increase in maximum TDO length.

Discussion

Involuntary commitment can result in both stigma and trauma to individuals with mental illness. Therefore, an important policy goal is to reduce involuntary hospital commitments. The findings are consistent with extending TDO length as a means to this goal. The study found that extending TDOs beyond the 48 hours required under current law in Virginia could reduce the level of coercion needed to restrain and treat people experiencing mental health crises. In our sample of Medicaid recipients, longer TDO periods were correlated with increased rates of dismissal. When hospitalization occurred, the stay was more likely to be voluntary rather than involuntary. Furthermore, longer TDO periods were correlated with shorter subsequent hospital stays. These results are promising and point to the need for more research to establish a causal link between TDO length and health outcomes.

Although improving health outcomes is in itself an important goal, policy makers must also consider the costs of proposed changes. Results from this study allowed us to make a preliminary estimation of the effect of changing Virginia's law to extend the maximum period of temporary detention before a commitment hearing from 48 to 72 hours. The results suggest a net increase of 1,782 treatment days; however, that estimate might be reduced if a minimum TDO of 24 hours was also implemented.

Ultimately, the impact on the state's budget of increasing the maximum TDO period would depend on the differences in costs and funding sources between TDO detention days and post-TDO hospitalization days, as well as on indirect costs related to public health and safety. This assessment highlights the complexity of the interaction between TDO length, hospitalization, and costs. Although the estimates provide an indication of the expected effect, more comprehensive data are needed to more accurately predict the budgetary implications of changing the TDO law.

This study has several limitations. The data available allowed us to exploit the natural variation that occurs as a result of provisions in the law and the institutional structure of the CSBs and courts. This quasi-experiment is valid only if we can rule out selection bias. The most likely source of bias is the influence of an individual's health on the length of both the TDO period and the hospitalization. For example, clinicians may fast-track certain individuals into involuntary commitment because they are familiar with the cases and know what the final disposition will be. These individuals would also have longer hospitalizations because of their health. However, evidence suggests that clinicians generally have little discretion over TDO length. For example, an informal survey conducted by Virginia's Commission on Mental Health Law Reform found that many jurisdictions hold TDO hearings every other day (

10). When a person is detained, the TDO hearing is scheduled for the next day that hearings are held. Other jurisdictions have different policies, but TDO length is still determined at the institutional rather than the clinician level. For example, officials at the Prince William County CSB reported that one aspect of their civil commitment process that helped make mandatory outpatient treatment more feasible was that they usually allow a full 48 hours for the TDO period (

10). This suggests that an individual's health does not determine TDO length and reduces the possibility that an individual's health is a third variable influencing both the length of the TDO period and the subsequent hospitalization.

There are additional sources of potential bias that may have influenced the results. The sample was drawn entirely from Medicaid recipients. However, persons with private insurance represent the largest proportion of inpatient mental health care users in Virginia (

11). Thus, to the extent that Medicaid recipients differ from other mental health patients, the results are not applicable to the broader population of the state. For example, we might expect women to be more likely to qualify for Medicaid, and, in fact, women made up more than half the sample. However, even if the results apply only to Medicaid recipients, they have important implications for public policy. In addition, certain types of individuals may be more likely to be committed over a long weekend, such as those with a history of violence or comorbid substance abuse, which represents another source of bias. We have no evidence of such a bias, but future research should explore this possibility.

The study found that the location of the TDO had a significant effect on hearing outcome and hospitalization length. This result is consistent with the Commission on Mental Health Law Reform hearing study, which found significant variation in TDO practice across the CSBs (

4). It is unlikely that the sample from the CSBs was random, and their record keeping accuracy also likely varied in systematic ways. Our data set contained a disproportionately large number of observations from the Blue Ridge Behavioral Healthcare CSB, which accounted for 37% of the total. In the jurisdiction served by this CSB, periods of TDOs were significantly shorter—a mean±SD of 1.36±.83 days, compared with 1.75±1.14 days for the rest of the sample. However, hospitalization days were not significantly different in this CSB location compared with the rest of the sample. Because each CSB structures its TDO period independently, it is not surprising that TDO periods differed by CSB. However, including the CSB as a control variable accounted for most of the variation. Some individual characteristics that influenced hospitalization but were not fully captured by the CSB variable may have been more prevalent in some CSB locations. Socioeconomic status might be an example, but it was not relevant in this study of Medicaid recipients.

Conclusions

This study is the first to clearly identify the relationship between TDO length and the result of the commitment hearing and subsequent hospitalization. Although more research is needed to determine costs, the findings are consistent with use of longer TDO periods as a means to improve health outcomes of individuals experiencing mental health crises.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by Virginia's Commission on Mental Health Law Reform. The authors acknowledge the data assistance of Rhonda Newsome, M.P.P., and Aaron Bloomfield, Ph.D.

The authors report no competing interests.