Stigma and discrimination can significantly compound the difficulties facing people with mental health problems (

1,

2) and their family members (

3). Several countries currently operate antistigma programs, including the United States, Canada, England, Scotland, New Zealand, Ireland, and Denmark, and others have planned such programs, including Wales, Sweden, and the Netherlands. The Scottish and New Zealand campaigns have reported improvements in public attitudes (

4,

5). However, none of the published evaluations of national-level interventions to reduce discriminatory behavior (

6–

10) have used ratings of discrimination experienced by users of mental health services.

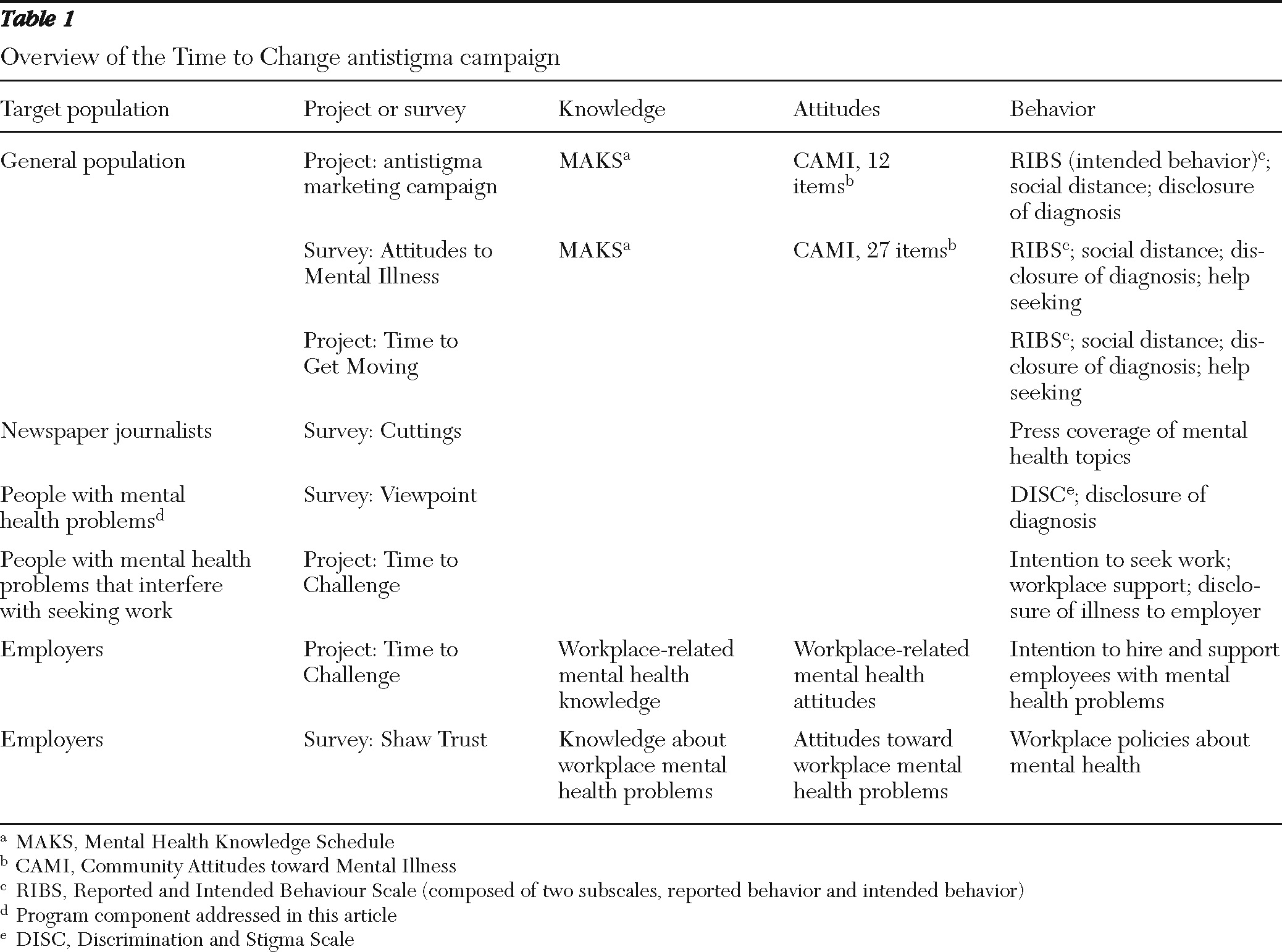

In January 2009, England's most ambitious program to reduce stigma and discrimination against people with mental health problems was launched: Time to Change (TTC) (

www.time-to-change.org.uk) (

11). It was funded for four years with £20.5 million from the Big Lottery Fund and Comic Relief. The interventions are delivered by two national charities (nongovernmental organizations)—Mind and Rethink Mental Illness. TTC coordinates national and local interventions to engage individuals, communities, and stakeholder organizations, such as health services and professional groups (

Table 1). A national marketing campaign aims to improve the attitudes and behavior of the general public toward people with mental health problems. The evaluation partner is the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College London. Mind and Rethink Mental Illness set a target to achieve a 5% reduction in discrimination experienced by people with mental health problems. This target formed the basis of our study hypotheses. The purpose of this study was to determine whether progress toward this target had been made 12 months after the launch. To do so we compared results of a large-scale national survey—the “Viewpoint” survey—of service users administered at baseline and 12 months later.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional telephone interview survey was conducted in 2008 and 2009 with separate samples of users of specialist mental health services. Data for service users were provided by the National Health Service (NHS). Users were adults ages 18 to 65 who were living in community settings, excluding those with a diagnosis of dementia. Our target sample for each year was 1,000.

Setting

Each year, five of the more than 50 NHS mental health trusts (mental health provider organizations) across England were selected to take part. The trusts were selected on the basis of the level of socioeconomic deprivation, determined from census data, in their catchment area. Catchment areas for all of England were ranked with a score calculated from census variables chosen on the basis of an established association with rates of mental illness (

12), including lack of access to a car, permanent general medical illness, unemployment, single marital status (never married, divorced, or widowed), and residence in housing that is not self-contained (for example, renting a room in a shared house). We then selected five trusts to ensure that areas in each quintile of socioeconomic deprivation were included.

Participants

Within each participating trust, staff in information technology or patient records used the computerized records database to select a random sample of persons receiving care for ongoing mental health problems. The sample size in 2008 was 2,000 per trust based on a predicted response rate of 25%, which had been previously achieved for membership surveys conducted by Rethink Mental Illness. Because the target sample was not achieved in 2008, the sample size in 2009 was 4,000 per trust. Records of individuals in the selected samples were checked by clinical care teams to confirm eligibility and to remove from the sample those who were judged at risk of distress from receiving an invitation to participate.

Invitation packs were mailed to eligible participants (8,917 in 2008 and 12,887 in 2009) containing information about the study, information in 13 languages on how to obtain the information pack in a language other than English (in 2009 only), and a consent form. A reminder letter was mailed to nonresponders after two weeks. Participants mailed signed consent forms, including contact details, to the research team.

Data collection

The Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC) (2; Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, et al., unpublished manuscript, 2011) was used to measure service users' reports of experienced discrimination, anticipated discrimination, social distancing, and positive discrimination. Further information on the development, content, and psychometric properties of the DISC is available elsewhere (2; Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, et al., unpublished manuscript, 2011). Briefly, the scale is interviewer administered and contains 22 items related to negative experiences of mental health-related discrimination. The 22 items cover 21 specific life areas, with one category for “other”; four items address anticipated discrimination. All responses are given on a 4-point scale, from 0, not at all, to 3, a lot. A “not applicable” option is used for items about situations that were not relevant to the participant in the previous 12 months (for example, items about having children or seeking employment) or to situations in which others could not have known that the respondent had a diagnosis. Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical history were also recorded.

Telephone interviewers were trained and supervised by members of the research team. Two-thirds were mental health service users (

13). Members of the interviewing team also had a part in design and development of the DISC. Allocation of participants to interviewers was based on interviewer availability. Once an interviewer made contact with a participant, up to three attempts were made to schedule an interview. Consent was confirmed by the interviewer before the interview began.

Data analysis

Analysis used SPSS, version 15. Overall scores for experienced discrimination were calculated by scoring any reported instance of negative discrimination as 1 and situations in which no discrimination was reported as 0. The overall score was then calculated as the sum of reported discrimination items divided by the number of items answered, multiplied by 100 to give a percentage of items in which discrimination was reported. For example, if a participant reported discrimination for 13 of the 22 items and reported that four items were not applicable, then the overall score would be 13/18×100=72. To compare the 2008 and 2009 samples for frequencies of experienced discrimination from each source (that is, from each DISC item), a binary variable—no discrimination versus any discrimination—was created for each DISC item.

In 2008, three items were used to measure anticipated discrimination. One item was split into two items in 2009. Therefore, we compared only the two items common to both years.

To determine whether the samples were representative of service users in England, sampling weights were calculated separately for each year to account for demographic disparities between years in both the Viewpoint data and the NHS data for characteristics on which good NHS data were available (that is, gender, age, and race-ethnicity). Weights were derived by dividing the proportion of NHS mental health service users by the proportion of Viewpoint participants for each characteristic. User information from the NHS dataset was selected to closely match Viewpoint inclusion criteria. Weights were then aggregated to provide an overall weight for each individual's combination of characteristics.

The study received ethical approval from Riverside NHS Ethics Committee.

Results

Participants

Response rates were 6% in 2008 and 7% in 2009. Interviews were conducted with 537 participants in 2008, and 1,047 participants in 2009.

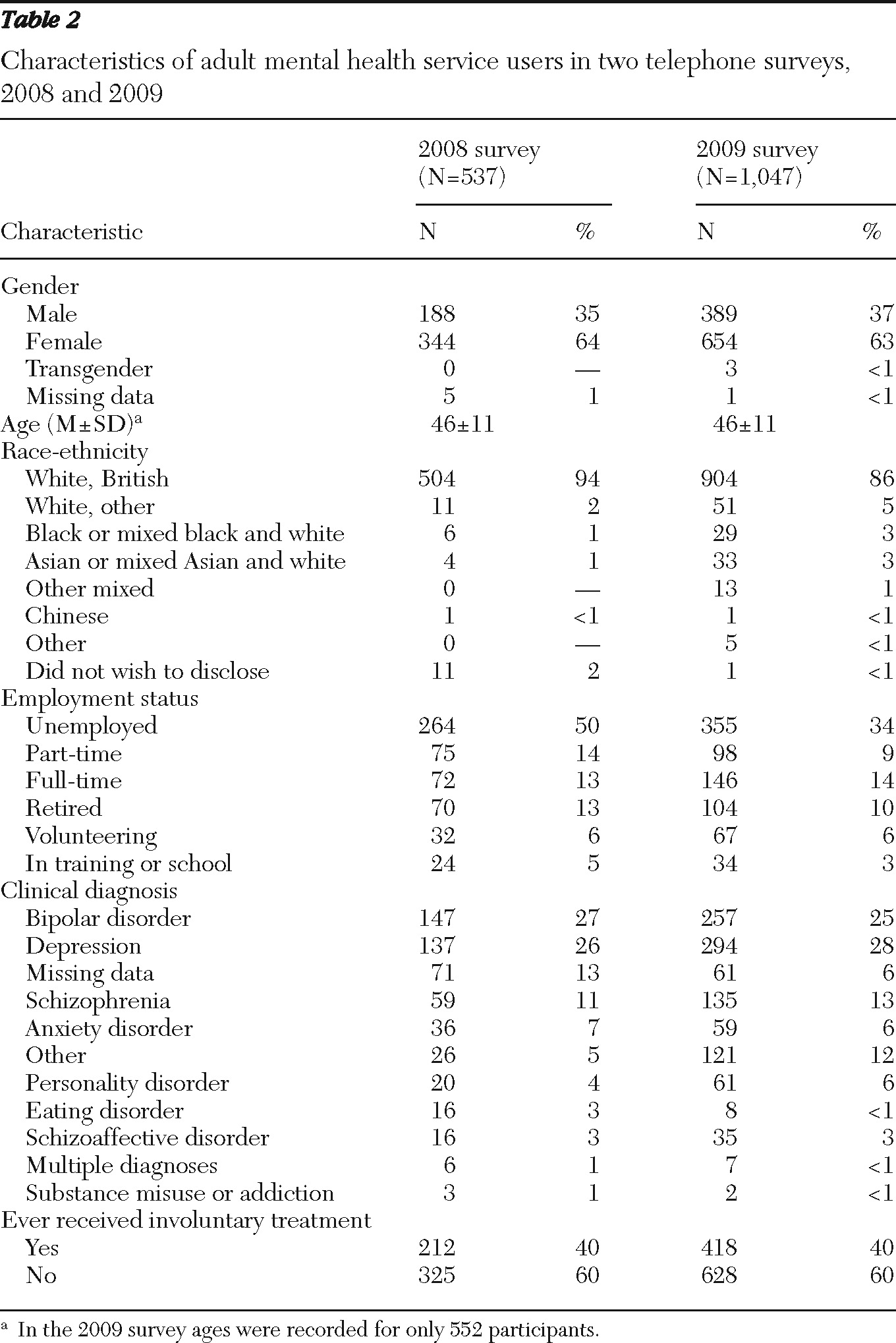

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the 1,584 participants. A chi square test indicated that the samples differed in race-ethnicity. Therefore, in addition to the basic chi square analysis, logistic regression that controlled for race-ethnicity was used. Weighted analyses gave very similar results in almost all cases. Therefore, we report the results of unweighted analyses and note the few differences where appropriate.

Experienced discrimination

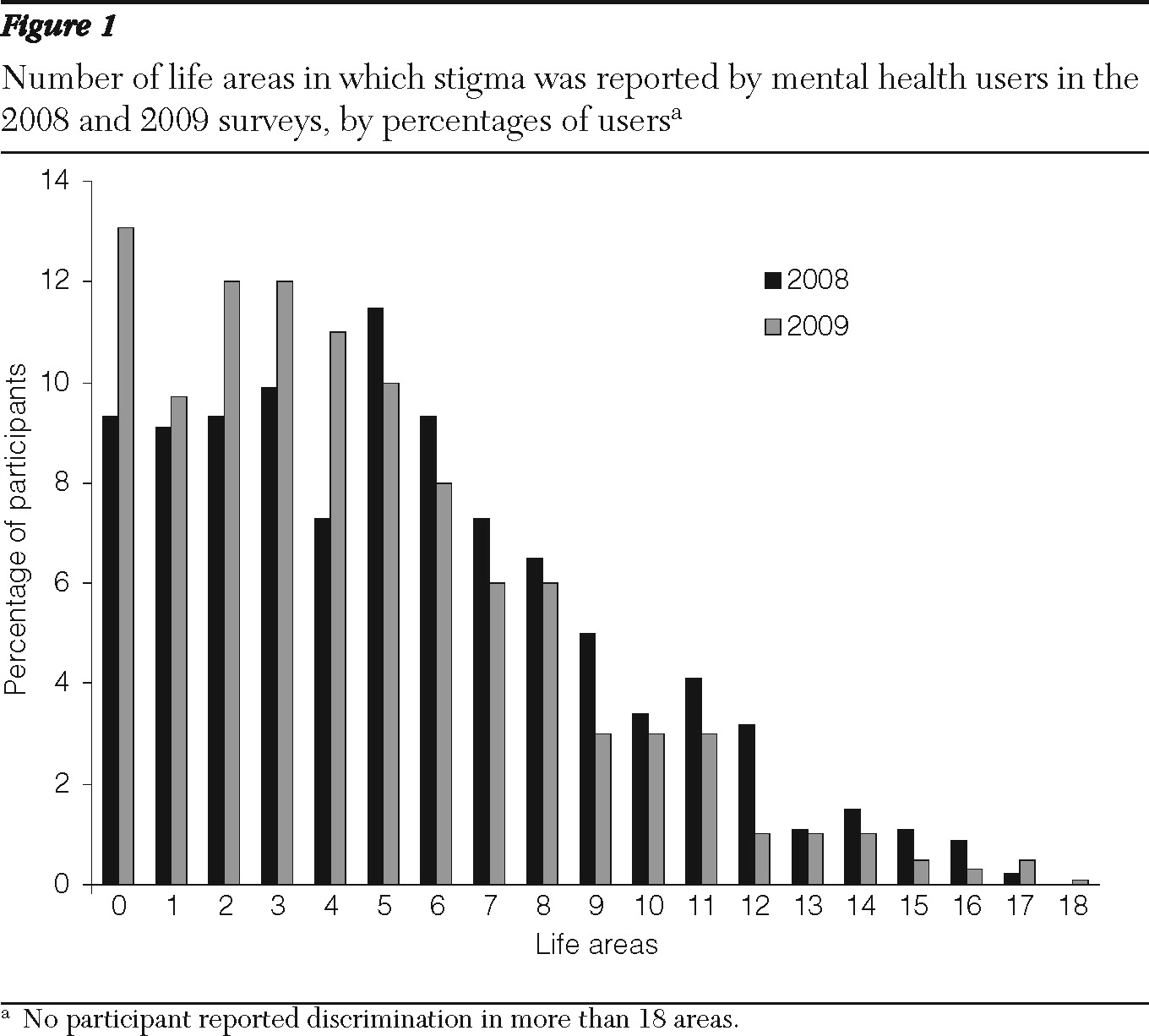

In 2008, 91% of participants (N=487) reported one or more experiences of discrimination, compared with 87% (N=906) in 2009 (χ2=4.86, df=1, p=.03). In 2008 the median number of life areas in which participants reported discrimination was five (interquartile range [IQR] 2–7), compared with four in 2009 (IQR 1–6). A Mann-Whitney test suggested a significant difference between the two years in the underlying distributions of the number of life areas of experienced discrimination (z=5.27, p<.001).

Figure 1 shows the overall profile of experienced discrimination for the 2008 and 2009 samples. In 2008 the overall median negative discrimination score was 38.5% (40% after weighting). In 2009, this score was significantly less at 26.7% (26.3% after weighting). Again, a Mann-Whitney test suggested a significant difference between the underlying distributions of scores (z=7.38, p<.001).

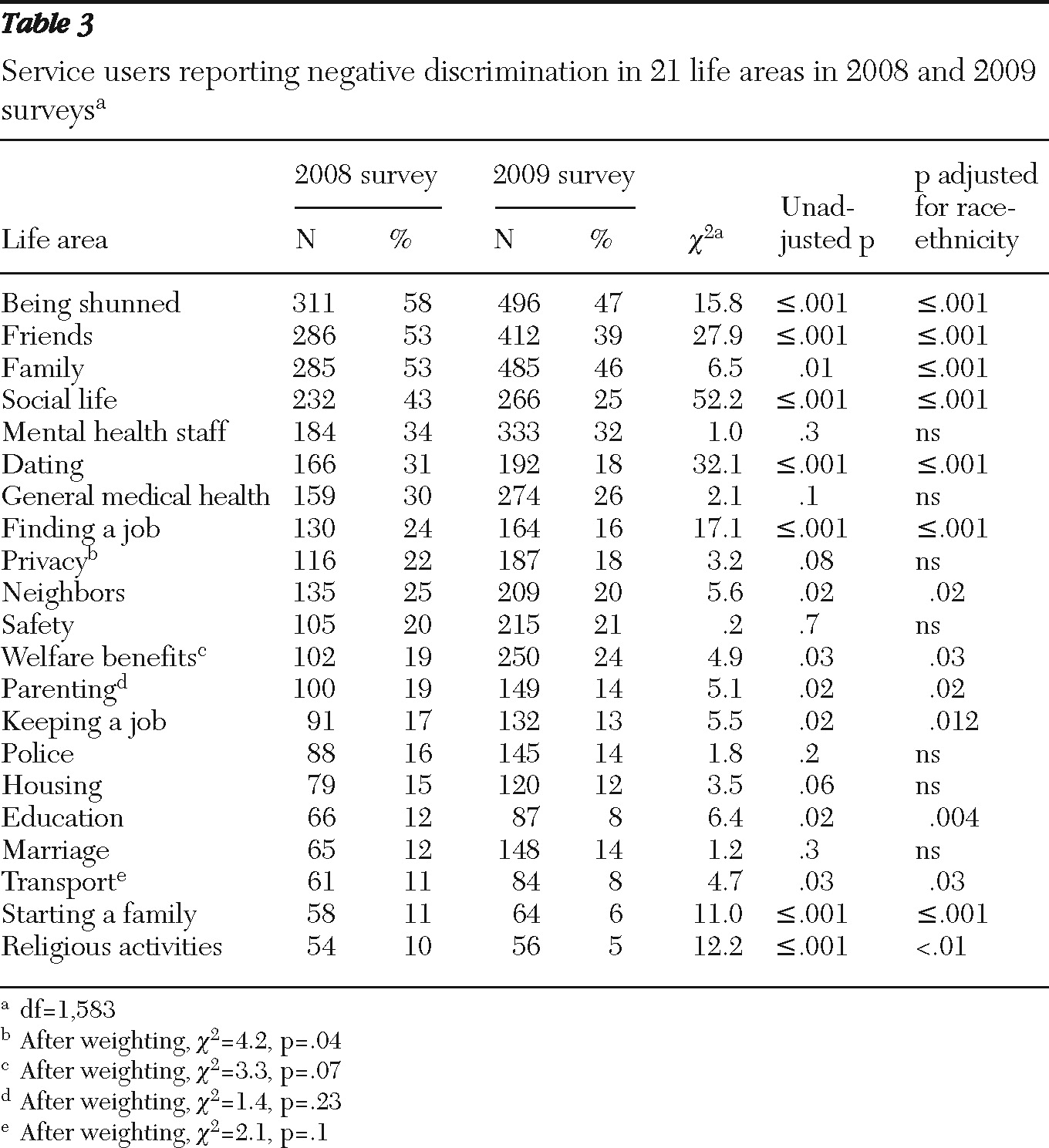

Table 3 shows the frequency with which participants reported negative discrimination in 2008 and 2009 for the life areas covered by the DISC. For 18 of the 21 items, the proportion of respondents reporting discrimination in 2009 was less than in 2008, but not all differences were significant. The exceptions were welfare benefits, marriage, and safety, but these increases were not significant after allowing for multiple testing (p=.002 after the Bonferroni correction).

In both years the most common reports of experienced negative discrimination were of feeling avoided or shunned by those who knew about the person's mental health diagnosis or by those with whom the person had frequent contact, including family, friends, and mental health professionals. Being shunned was the form of discrimination most often reported in both years, although the reported frequency was 10% lower in 2009 (χ2=15.78, df=1, p<.001). In 2008, respondents cited the categories of friends and of family (53% for each) as the second most frequent source of experienced discrimination. In 2009, family was the category cited second (46%) and friends were cited third (39%). Again, discrimination was reported significantly less frequently for these items in 2009; the proportion citing friends as a source declined from 53% to 39% (χ2=27.86, df=1, p<.001), and the proportion citing family declined from 53% to 46% (χ2=6.47, df=1, p=.001).

In 2009, 32% of participants reported that they had been treated unfairly by mental health staff, compared with 34% in 2008, a nonsignificant difference. In 2009, just over a quarter (26%) reported discrimination in their general medical health care, compared with 30% in 2008, also a nonsignificant difference.

Awareness of the campaign and reported discrimination

To examine whether awareness of TTC was associated with reports of discrimination after the program's launch in January 2009, we asked participants in the 2009 sample whether they were aware of TTC. The discrimination scores of the group who reported awareness of TTC (N=266) and the group who did not (N=770) were not significantly different (mean±SD scores of 30.0±23.1 and 32.1±23.4).

Anticipated discrimination

In 2009, 73% of participants (N=759) reported feeling that they had to conceal their mental health status to some extent. In 2008, the figure was 75% (N=405). A chi square test indicated that the difference was not significant. However, the proportion of participants who reported that they had stopped themselves from looking for a close personal relationship was significantly lower in 2009 than in 2008 (45% compared with 54%; χ2=9.83, df=1, p=.004).

Social distance

One DISC item measured social distance. In 2009, almost three-quarters of participants (73%, N=718) reported that they had made friends outside mental health services in the past year, compared with 64% (N=315) in 2008 (χ2=15.39, df=1, p<.001).

Discussion

Experiences of negative discrimination were extremely common in this sample of mental health service users. The reported frequency of such experiences appeared to fall after the TTC was launched; however, this change cannot be attributed with certainty to the social marketing campaign, particularly because only a single baseline time point was used and it is not known how experienced discrimination was changing before 2008.

In general, service users reported more discrimination from people with whom they had the most frequent contact (2; Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, et al., unpublished manuscript, 2011). This finding suggests that NHS mental health services need to do more to support and educate caregivers in their roles. However, the frequency of discrimination by mental health professionals reported (about a third of participants in both years reported this group as a source of discrimination) suggests caution about advocating greater support and education of caregivers by mental health professionals. Although these results are consistent with other research on mental health professionals' attitudes (

14), the lack of change from 2008 to 2009 contrasts with most of the other results and may reflect a response bias in the survey sample. Alternatively, service users' awareness of the campaign in 2009 might have raised their expectations of behavior from mental health professionals, and these expectations may not have been met. However, only 25% of the sample reported being aware of TTC, and the difference in experienced discrimination was not significant between those who were and were not aware. Furthermore, this null finding means that no evidence was found that discrimination reporting was affected by campaign awareness, which also applies to the overall discrimination score. Professionals' attitudes and behavior may be more resistant to change because professionals come into contact with service users who have the most severe course and outcome (the “physician's bias”). Furthermore, contact occurs in the context of an unequal power relationship (

15), and prejudice against clients is an aspect of burnout, which is not uncommon among mental health professionals (

16).

The findings suggest that mental health professionals may require a more targeted antidiscrimination program than the TTC social marketing campaign. The existing Education Not Discrimination (END) program (

11,

17), delivered to medical students as part of TTC and based on previous effective work with other groups (

18,

19), could be adapted to include mental health staff. An alternative approach would be to implement interventions to prevent or treat burnout. Only 25% of the participants indicated that they were aware of TTC, which is a much smaller proportion than the 40% of the targeted demographic subsection of the general population (ages 25 to 45 with middle incomes) that reported awareness of the campaign during or after a burst of campaign activity (Evans-Lacko S, Rose D, Rüsch N, et al., unpublished manuscript). However, the TTC campaign is not aimed at service users, and this finding may perhaps be expected.

Results indicate that discrimination in the area of employment is improving; however, reported discrimination in this area is consistent with findings of research showing that many employers lack sufficient knowledge and procedures to address mental health problems in the workplace (

20). Continued efforts, such as those by Time to Challenge, a component of TTC, are needed to educate both employers and persons with psychiatric disabilities about the rights of disabled employees and job candidates. Specifically, the U.K. Equality Act 2010 made it unlawful for employers to ask about mental health status before a job offer is made, except in certain defined circumstances. We would thus expect the frequency of discrimination in this area to fall from 2011 onward.

Overall, the levels of discrimination reported were high, which could have been predicted on the basis of previous research (

10,

14,

21). However, the study reported here documented service users' reported experiences of stigma and discrimination, which is a departure from past research based on hypothetical vignettes, and provides insight into the daily experiences of stigma and discrimination among people in England with a mental disorder diagnosis. Moreover, the study findings could be used to ensure that antidiscrimination efforts are designed for appropriate groups.

The key limitation of this study is the low response rate. After the 2008 survey yielded a 6% response rate, changes were made in the 2009 recruitment strategy. To facilitate participation by non-English-speaking service users, we included a “language sheet” with information in 13 languages (accounting for 90% of translation work in the most ethnically diverse NHS mental health trust) about how to obtain the invitation pack in a language other than English. In addition, the language in the invitation pack was made clearer and more concise. Despite these changes, only 7% of people who received an invitation pack were interviewed in 2009.

Several factors may have affected the response rate. The recruitment method relied on sampling through NHS trust patient databases, which may not have been accurate. At least 176 packs were returned as undeliverable to the trusts. It is likely that more were not delivered to the intended recipient. There were several national postal strikes during the first months of mailings to potential participants in 2009. The strikes caused delays in receipt of completed consent forms and therefore in interviewers contacting participants, which also may have affected the response rates. Finally, we did not have funding to compensate participants.

Response bias may have resulted in overrepresentation of persons with more experiences of discrimination. Although we cannot fully determine the extent to which this was the case, we were able to determine the extent to which the sample was representative of the entire population of noninstitutionalized NHS mental health service users aged 18 to 65 with respect to age, race-ethnicity, and gender. Our sample underrepresented younger people, nonwhite ethnic minority groups, and men—to a greater extent in 2008 than in 2009. However, the weighted analyses yielded almost identical results.

Despite the low response rates, the sampling design for this study is an improvement over those of previous surveys in England, in that the sample was drawn from persons using NHS mental health services across England rather than from memberships of national mental health charities as in previous research. Further, the high rates of experienced discrimination reported are consistent with data from surveys that used the same instrument and different data collection methods that yielded higher response rates—both face-to-face surveys (

2,

22) and a recent postal questionnaire to service users in New Zealand (

23). In addition, although use of a postal questionnaire yielded a somewhat higher response rate, this method prevented validation by an interviewer of the experiences as examples of discrimination.

Changes were made to simplify the wording of the DISC used in 2009, which may have affected the results. The main change was that “treated differently” was replaced by “treated unfairly” in each question about experienced discrimination. The changes lowered the Flesch-Kincaid reading grade to level 7.4 (understandable by the average U.S. 7th or 8th grader) from level 13.2 (understandable by the average U.S. college freshman). However, subsequent validation of the DISC showed that the questions elicited similar responses (Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, et al., unpublished manuscript, 2011). Further, although each question was reworded in the same way, the revisions did not result in the same pattern of change in endorsement across all items from 2008 to 2009. Instead, the frequency of reporting increased for three items and fell for the rest.

We do not know the possible effects of experiencing less discrimination; for example, is it associated with increased access to employment or more participation in leisure activities? We will explore these questions in future aspects of the evaluation. We will also seek to delineate different types of discrimination and the extent to which these vary by source. Examples given by interviewees ranged from being patronized, overprotected, or treated like a child to being shunned, rejected, or at times abused.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the Big Lottery Fund; Comic Relief; and SHiFT (Shifting Attitudes to Mental Illness), U.K. Government Department of Health. Dr. Henderson, Ms. Corker, Ms. Hamilton, Dr. Rose, Mr. Williams, and Dr. Pinfold are supported by a grant to TTC from the Big Lottery Fund and Comic Relief and a grant from SHiFT. Dr. Henderson, Mr. Williams, and Dr. Thornicroft are funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) applied program grant RP-PG-0606-1053 awarded to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Rose and Dr. Thornicroft are also supported by the NIHR Specialist Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, and the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Henderson is also funded by a grant from the Guy's and St. Thomas' Charity. The authors thank the participating NHS Trusts, the Viewpoint interviewers,and Sue Baker, Maggie Gibbons, Paul Farmer, Paul Corry, Mark Davies, Dorothy Gould, and Jayasree Kalathilfor their collaboration. The funders did not contribute to the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or the U.K. Government Department of Health.

Dr. Thornicroft has received research grants from Lundbeck UK. The other authors report no competing interests.