The concept of recovery from schizophrenia and related disorders has been widely accepted as a primary goal for individuals with mental illness (

1–

3). Attempts to better define recovery have been enriched by disparate perspectives from service providers, service users and their families, and researchers (

4–

12). Whitley and Drake (

13) have recently proposed a parsimonious model comprising five superordinate dimensions to conceptualize recovery, namely clinical, existential, social, functional, and physical. Other previously well-articulated models of recovery include some of these dimensions, but each may have emphasized one or more of these dimensions at the expense of others (

3,

4,

14–

16).

Most of the literature on recovery from psychotic disorders is based on individuals' experiences with many years of illness and its treatment (

8). Little is known about how individuals early in the course of their illness view their recovery. This is important for several reasons. The recent increase in provision of specialized early-intervention services for persons with a first episode of a psychotic disorder is likely to improve short- and long-term outcome trajectories (

17–

19). These services incorporate a philosophy of hope, a client-centered recovery orientation, and phase-specific multiple psychosocial interventions. Furthermore, individuals in the early phase of illness may approach their recovery with a more hopeful perspective either because of less experience of consequences of the illness and its treatment or because they are receiving more comprehensive care. There is also evidence that ideas about the illness are different for individuals early in recovery in the course of illness versus later (

20).

Despite considerable research on symptomatic and functional outcomes for individuals treated in early-intervention programs for psychotic disorders (

21,

22), there are no estimates of how individuals identify themselves as recovered and what it means for them to be recovered. This article explores the personal meanings of recovery among individuals who have been treated for at least two years in a specialized early-intervention program for psychotic disorders.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-three consecutive individuals presenting for a follow-up assessment at a specialized early-intervention service (

www.pepp.ca) were approached (

23). Thirty agreed to participate in a one-time qualitative interview, conducted between 2006 and 2008, to explore subjective ideas of recovery. Two men and one woman refused to participate on account of a lack of time. Participants had been in treatment for three to five years, were young (mean±SD=25.9±5.3 years), and provided informed consent as approved by the University of Western Ontario Ethics Board for Health Services Research.

Measures

Qualitative interview.

A semistructured interview guide, designed to elicit in-depth accounts of the personal perceptions of psychosis and recovery based on the guidelines by Smith and Osborn (

24), included self-assessment of recovery, as well as identification of critical components and general ideas about the personal meaning of being recovered. Individuals who identified themselves as currently recovered were asked to elaborate on the meaning of recovery, and those who indicated that they were not recovered were asked to describe what would constitute being recovered. The interviewer did not use the terms schizophrenia and psychosis and instead used participants' terms about their psychiatric illness. Interviews were conducted by DW, ranged from one to three hours, and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The data were analyzed with interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) (

25). With this type of analysis, the researcher's goal is to develop an in-depth understanding of the individual's account of the processes by which he or she makes sense of personal experiences. This exploration of the meanings used by informants is undertaken through a subjective and reflective process of interpretation of an individual's account by the researcher. IPA provides a set of flexible guidelines adaptable for specific research purposes (

26). A sample size of 30 participants allowed us to account for likely variation in recovery experiences and to explore patterns of similarity and difference in meaning of recovery within the group.

The transcripts were examined sequentially, in the order that interviews were conducted. Initial ideas were transformed into themes that attempted to capture the essential meaning of the text. These themes were subsequently combined into general higher-order themes for each transcript before general broad categories across cases were identified. This process involved searching for patterns and connections as well as contradictions and tensions between ideas. We also attempted to elucidate shared aspects of the participant's experience in relation to the general theme and then grouped those aspects into meaningful categories. The analysis involved constant reflection and reexamination of the verbatim transcripts to confirm that constructed themes were meaningfully and closely connected to the original transcripts.

Although the goal of IPA is to enhance understanding of the content and complexity of meanings rather than to measure their frequency, we were interested in potential variations in the experience of being recovered. We also examined the distribution of categories within and between individuals. Pertinent examples of applications of IPA procedures to construct meaning-based typologies among subjective accounts were consulted for guidance (

27).

Results

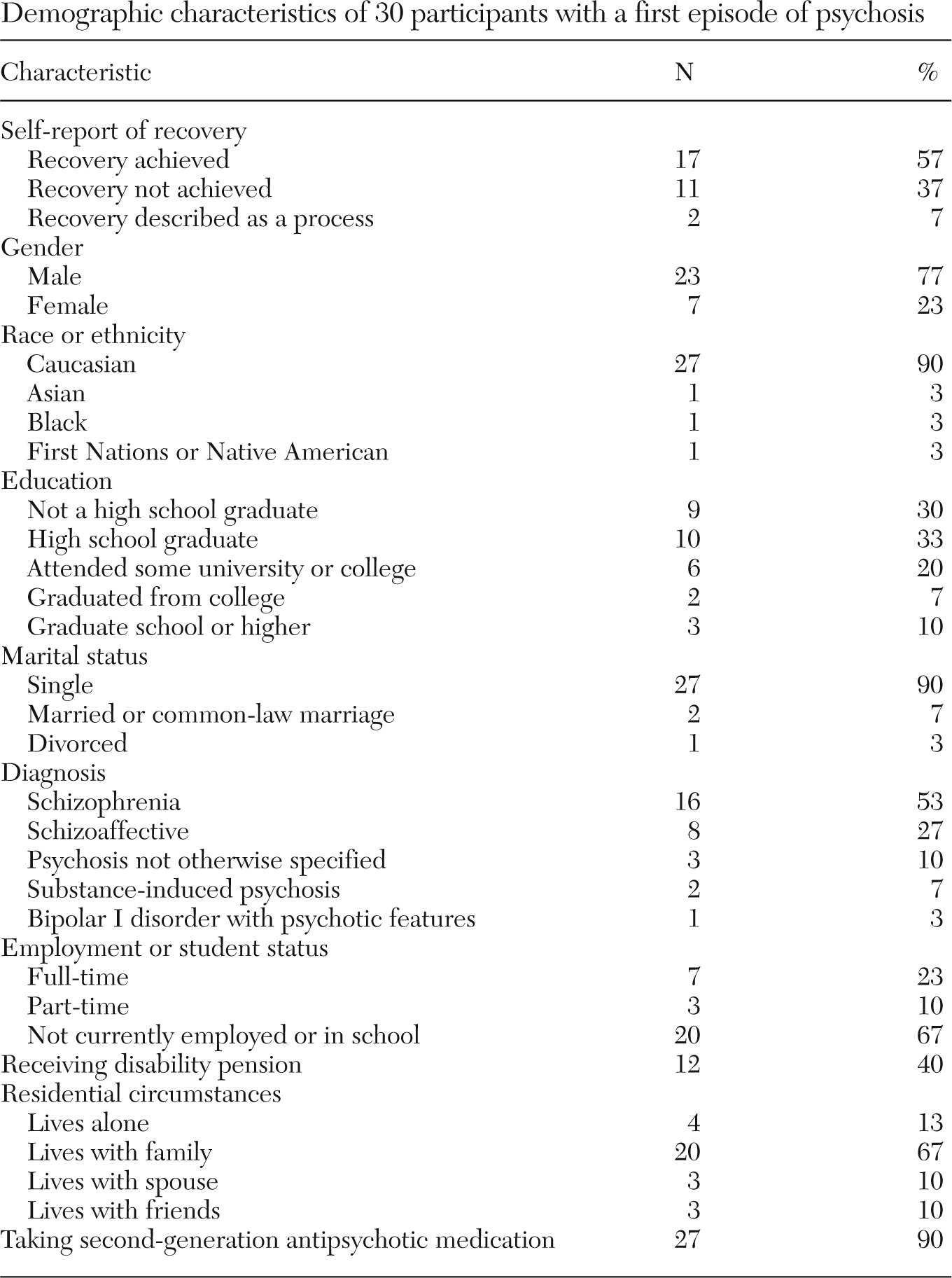

Clinical and demographic information is presented in

Table 1. Diagnosis was determined in the first year of entry to treatment through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (

28) and was conducted by a trained researcher not involved in the patient's treatment. Whereas the SCID-I interview was conducted as part of a study of longer-term outcomes of first-episode psychosis, the rest of the data presented here were collected exclusively for this study.

Of the 30 individuals interviewed, 17 (57%) stated that they had recovered according to their personal definition of recovery. Nine of the 11 individuals of the sample (37%) who considered themselves not yet recovered noted that they had nonetheless made considerable progress toward recovery. Only two individuals (7%) indicated that although they could identify elements indicative of progress toward recovery, their idea of being recovered was not an end state but rather an ongoing, lifelong process.

Qualitative definitions of recovery

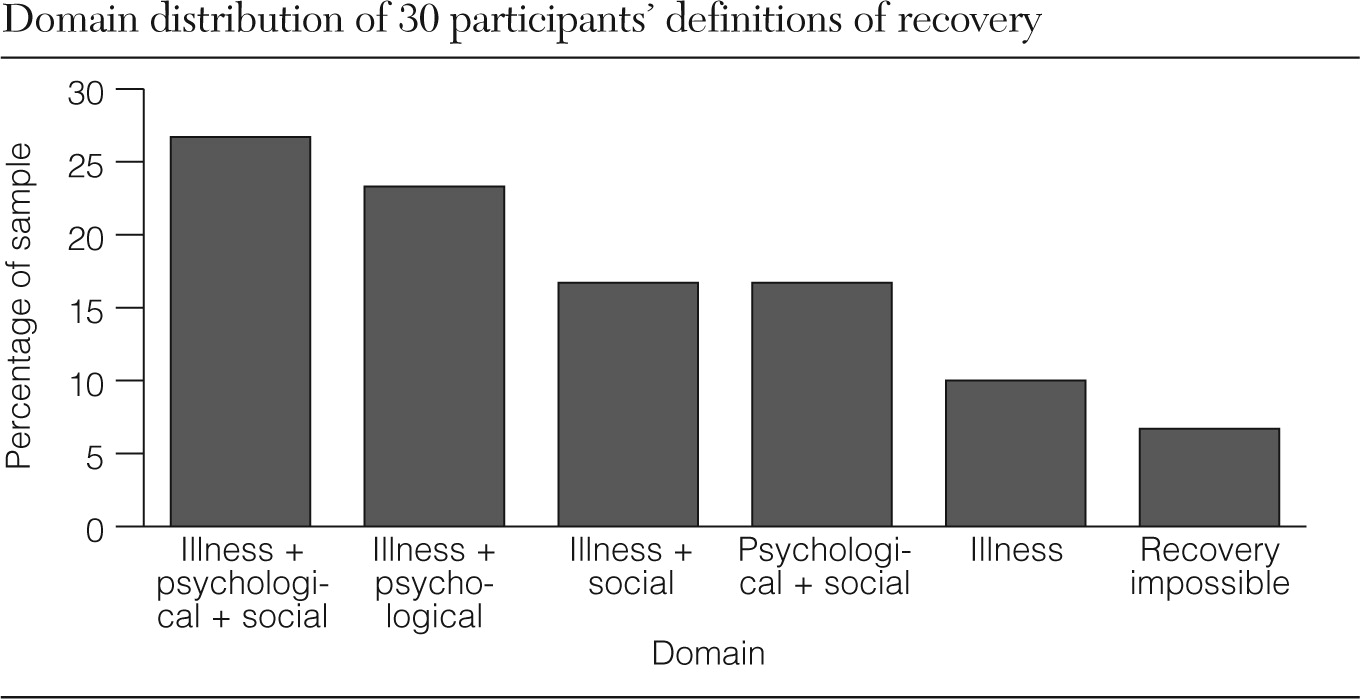

Analysis of themes regarding recovery revealed three domains of recovery, namely (in order of prevalence) illness (N=24, 80%), psychological and personal (N=20, 67%), and social and functional (N=18, 60%). Two additional distinct recovery themes that emerged were the impossibility of recovery (N=2, 7%) and participation in treatment as a means to recovery (N=11, 37%).

Illness recovery.

The category of illness recovery incorporates aspects of alleviation of symptoms: “I haven't recovered completely. They've been bad, lately, the symptoms, they're still there, so I can't say I'm completely recovered.” Twenty-three individuals (77%) included one or more of affective, cognitive, and positive or negative psychotic symptom domains in the recovery definitions. Most of them focused exclusively on positive symptoms.

A minority of individuals (N=3; 10%) described illness recovery not as an elimination of psychotic symptoms but as subjective control over the extent and influence of the symptoms and reduction of distress associated with symptoms. For example, a participant described it this way: “I've recovered. … Even the thoughts that are there now … aren't. … I do have thoughts that could take over, but they don't. Without acting on it and placing a lot of significance … to take the thoughts with a grain of salt. I have to stay strong … and I have to know where to draw the line.”

Psychological and personal recovery.

This category encompasses experiences of regaining a sense of control and a coherent sense of self. Twenty participants (67%) included one or more subthemes (below) of psychological recovery in their recovery definitions. “Knowing something was wrong” was described as an awareness of change in one's self-experience. “Understanding the illness” reflected having a coherent and plausible framework or explanation for the experience of psychosis congruent with the person's experience and beliefs. This was directly linked with “acceptance of illness,” which referred to becoming reconciled with one's perspective on the meaning of the experience (whether the illness will be short term or chronic). Perception of “being able to do something about it” included identifying potential (personalized) avenues for agency and control of the experience and the experience of being able to enact these strategies. This component of recovery often involved specific lifestyle changes to support one's recovery. “Back to being myself/feeling better about myself,” was experienced as a restored sense of self that encompasses multiple dimensions. This component included reversing the loss of self that was experienced both as a direct result of the illness and as a part of the social and personal consequences of the illness. Finally, “putting it in perspective” was described as perceiving one's self and experiencing one's life without the illness as a dominant part of day-to-day living. The component themes of psychological recovery reflected various recovery processes but were seen as indicative of being recovered once important tensions were resolved.

Social and functional recovery.

Eighteen (60%) participants included domains of both social and functional recovery in their recovery definition. This category incorporates the themes of being able to or knowing how to talk to people, working or going to school, having friends, and having a partner or spouse. At its essence, the meaning of social recovery was attaining a positive social identity and social inclusion: “I'll know if recovery's occurred for myself when I do get a job and I keep the job. And I do make new friends and get into a relationship. So once those things start happening and I'm able to keep those things in my life, then I'll know recovery has happened.”

Sixteen individuals (53%) identified meaningful engagement in a valued role as part of recovery. Of these, 12 indicated that employment is an essential component of recovery. The weight given to role resumption in recovery varied among individuals. For some, the valued role did not have to be congruent with a role an individual had before onset of illness, whereas others emphasized the importance of attaining developmentally normative functioning.

Twelve participants (40%) specifically identified social participation such as peer relationships and romantic attachments in their recovery definitions. Although relationships with family were often described as playing a crucial role in recovery, these relationships were only rarely described as a specific component of the meaning of being recovered.

Some individuals indicated that social recovery was (or would be) experienced as establishing independent adult living, emphasizing that being recovered involved competence and maturity as a young adult. Restored social confidence, described as an ability to confidently approach others and engage in relationships, was also a critical component of recovery for many individuals.

Recovery domain combinations

Only three individuals (10%) identified an exclusive illness recovery typology, and no participants reported recovery definitions exclusive to psychological or social domains. More than three-quarters of participants (N=23) proposed a composite definition of recovery that comprised two or more recovery domains. Five combinations of recovery domains were indicated in the sample (

Figure 1).

Treatment and recovery appraisal

Treatment participation (such as attending clinic appointments) was a component of being recovered for many individuals. Medication-related themes were a critical part of being recovered for 11 (37%) participants, albeit with opposing perspectives within this group. For six participants, taking medication was an integral component of recovery, whereas for five others, not taking medication was a prerequisite for recovery. The latter group felt that an ongoing need for medication precluded recovery because the need for medication signaled to them that they remained vulnerable to relapse. Whereas most participants had experienced a feeling of being recovered while acknowledging the continued presence of illness or vulnerability to relapse risk, two individuals (7%) felt that an experience of being recovered from psychosis was impossible, because the illness was inevitably a chronic condition: “I can't say I'm recovered, because I'm still ongoing, you know. I'd like to have a recovery. I never thought about that, I never talked that term with the doctor before, so I don't know. Maybe I am recovered, with the voices being gone, but they said I'd have to be on medication for the rest of my life. It doesn't go away. I'm not recovered. That would make me not mentally ill anymore.”

Failure to recover

The 11 individuals (37%) who described themselves as not recovered typically indicated that this state was due to nonachievement of desired social roles or not having yet experienced remission of symptoms. Some of these individuals described having had a previous recovery when they had a period of symptom alleviation or had returned to valued roles. These participants expressed confidence that they would once again recover. In contrast, others not recovered expressed disappointment, frustration, and even despair about this fact. They often described their experience with psychosis as a prolonged, difficult battle with a powerful and destructive force over which they had limited control. In response to the question “Would you say you have recovered?” one woman responded: “I don't know. [Recovery] could be unreachable for the rest of my life. I don't know. According to people, I'll be able to get out of it, but is there such a thing as 100% recovery in psychosis?”

Discussion

The three domains of personal recovery reported here (illness recovery, psychological and personal recovery, and social and functional recovery) are similar to four (clinical, existential, social, and functional) of the five dimensions proposed by Whitley and Drake (

13). However, none of the individuals in our sample discussed physical health or spiritual aspects of recovery. This may partly be a function of younger age and an earlier stage in the course of illness. Most individuals described being recovered as the achievement of specific benchmarks within these domains. Distinct differences in the domains and benchmarks used illustrate the broad range of meanings of recovery even for individuals early in the course of treatment.

Domains of recovery

The domain of psychological and personal recovery contains elements of existential recovery (

13) and is consistent with recent research supporting the importance of acceptance of illness (

10,

29–

31) and obtaining a sense of control over the illness (

32–

34). Examples of variation within this domain of being recovered include recapturing one's “old self,” taking on an altered and new identity, and a perception of self (“recapturing self”) or a desired self in which one's identity is not dominated by the illness. This theme supports the importance of a positive and efficacious sense of self as an essential aspect of recovery from schizophrenia (

15,

35–

38).

Even early in the course of psychotic disorders, definitions of recovery described by service users generally do not exclusively indicate remission of symptoms. Nevertheless, there are noteworthy variations in the importance attached to symptoms. In contrast to the consumer literature, which asserts that recovery from serious mental illness does not require remission of symptoms or other deficits (

39), only three (10%) of our participants explicitly indicated that elimination of psychotic symptoms was not required for recovery. Symptom alleviation was regarded by many (77%) as an essential component of recovery, a criterion that is supported by recent quantitative research examining the predictive value of remission of positive and negative symptoms for improved functional outcome in first-episode psychosis (

40). The importance that some participants attached to a sense of control over symptoms and associated distress is also consistent with the literature (

41–

43).

Inclusion of meaningful engagement in valued roles and participation in social relationships confirms the importance of meaningful social connections (

10,

37,

44) and friendships in the early recovery experiences of young adults (

45). These themes in the definitions of recovery clearly demonstrate the overlap between social and functional domains of recovery (

46).

The meaning of being recovered

The observed variation in the perceived feasibility of becoming recovered extends Estroff's (

47) finding that seeing one's condition as acute or chronic is an important dimension of illness understanding. The presence of opposing perspectives regarding the role of medication in recovery definitions suggests the influence of variations in contextual notions of mental illness in personal models of recovery and is consistent with other reports from service users with both longer-term (

9,

48,

49) and recent-onset psychotic illness (

50). It appears that the understanding of maintenance medication in recovery definitions may differ between service users and providers (

6), with some service users identifying medication discontinuance as a necessary condition of recovery. It is important to appreciate these conflicting perspectives in order to avoid hindering effective communication and mutual understanding between service providers and service users. This is especially important during the early course of illness, when long-term trajectories are established and likely to be malleable.

While acknowledging that many of the processes of recovery were ongoing, most individuals in this study appeared to easily conceive of recovery as an end state, albeit one that some believed could be repeatedly lost and regained. Our findings that recovery is a process for some and an end in itself for others (symptom alleviation or optimal functioning) support previous evidence about the personal meaning of being recovered as a process versus a multidimensional collection of outcomes (

48,

49). Identification of specific benchmarks of a successful, complete recovery may be related to a more hopeful attitude about the future, which may be a function of younger age, less experience with negative consequences of psychotic illness and its treatment, or exposure to a more comprehensive, phase-specific client-centered approach to treatment in a specialized early-intervention service.

Our results have implications, especially for individuals entering the treatment system for the first time. Their longer-term trajectories of outcome could be positively influenced by taking into consideration young peoples' own perspectives and meanings of recovery. For example, the emphasis on the critical importance of social recovery reinforces the early inclusion of interventions, such as supported employment and supported education initiatives, that promote positive functional and social outcome. The emphasis on peer relationships among participants confirms the importance of increasing opportunities to interact with successfully recovering peers and making such interactions a primary focus of recovery-oriented care (

44). Clinicians should also be aware of the divergent views on whether taking medication is compatible with recovery. Addressing these areas will be essential for ensuring full, meaningful, and sustained recovery for individuals experiencing a first episode of psychosis (

46).

The findings of this study could also contribute to the development of outcome measures of recovery relatively early in the course of illness. Such measurement should include empowerment, self-esteem, hope, and well-being as part of psychological recovery; measurement of subjective distress associated with symptoms; and social functioning, particularly with respect to peer relationships and employment.

This study had several limitations. The predominantly Caucasian sample may not have reflected ideas of recovery that can be generalized to individuals from other racial or ethnic backgrounds. Recovery definitions were elicited at a single time point and cannot address changes over time in conceptions of recovery (

47). The entire sample was fairly continuously engaged in treatment in a specialized early-intervention service and may not represent all patients in the early phase of psychosis, given that some patients drop out of treatment even in early-intervention services. A larger than usual sample size for an idiographic method (IPA) may risk potential loss of subtle nuances in meaning. To minimize this risk, a deliberate attempt was made to carry out an equally attentive analysis for each case, and several cycles of analysis were repeated.

Conclusions

Despite some limitations, this study confirms a framework for exploring variations in recovery definitions through delineating recovery typologies from the lived experiences of service users during the early phase of treatment of a psychotic disorder. More research is needed to understand how concepts of recovery are shaped over time and whether the more specialized approach to treating first-episode psychosis will result in more positive perspectives on the part of service users regarding their recovery.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant 57925 from Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The senior author (AM) is supported by the Canada Research Chair Program.

Dr. Malla has received honoraria for conference presentations and lectures by and participation on advisory boards of the following pharmaceutical companies: Janssen-Ortho Canada, Pfizer Canada, BMS, AstraZeneca, Lundbeck, and Merck. He has also received research funding for investigator-initiated research from Pfizer Canada, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and BMS. The other authors report no competing interests.