Expenditures by the health care system in general, and particularly in the United States, are growing as the amount and cost of services increase (

1). Hospitalization is among the most costly health care services and is projected to be the most costly by 2014 (

2). Conceptualizing patient-level health care costs longitudinally, we propose that one goal of a health care system is to minimize expenditures over the year after inpatient medical stays by treating patients' underlying general medical as well as psychiatric conditions. Many researchers have examined issues such as these, in particular diseases and their costs over time (

3,

4). This study adopted a patient-centered perspective (

5) by examining the impact of a new inpatient event on health expenditures in the subsequent year and in particular the potential role of postdischarge mental health care in limiting subsequent costs. These exploratory analyses of administrative data are aimed at motivating future research to address mental health care in general medical hospitalizations.

This study conceptualized a new inpatient stay as a potentially critical event relevant to the subsequent health of patients. The intuition of this approach is that there are many possible conduits for understanding the costliness of a health care system, but one important conduit is the sequence of costly care that occurs after a new inpatient admission for a general medical problem. We conceptualized a new inpatient medical admission as an event related to a chain of future health care utilization and related costs. We identified an inpatient medical admission as one that follows a one-year period of active outpatient use with no record of hospitalization in that prior year. We examined the effect of utilization of mental health care in a 30-day postdischarge period on the one-year health care costs for persons with inpatient medical admissions.

Postdischarge mental health care is one potential mechanism that we propose will be particularly important in limiting health care costs after an inpatient general medical admission for patients with mental health conditions (

6,

7). Patients with chronic illnesses need continuity of both general and mental health care between the inpatient and outpatient settings to be able to achieve and maintain clinical outcomes (

8,

9). Mental health comorbidities are specifically conceptualized as a key risk factor in the care of patients who have been admitted for a general medical issue. One study found that individuals with prior hospitalizations and positive screens for depression were three times more likely than other patients to be readmitted (

10), but no similar literature exists for patients for whom the index admission is not preceded by recent inpatient stays. Indeed, there is surprisingly little literature on the transitions in mental health care after a general hospital discharge. Mental health conditions can increase the complexity of medical care (

11,

12) and thereby increase the costs associated with inpatient treatment. Therefore, we propose that postdischarge mental health treatment can be protective against health care costs in the year after an inpatient discharge.

Factors that may increase one-year-subsequent health care costs include patient age, sex, socioeconomic status, comorbid health conditions, case complexity, complications during hospitalization, day of discharge, prior hospitalization, and length of stay (

13). This study focused on the relationship between postdischarge mental health care and length of stay in limiting one-year-subsequent costs. Severity of medical disease and injuries are related to length of stay (

14). Comorbid psychiatric conditions are prospectively associated with increased length of stay, when severity of general medical illness is controlled for (

15) and have been associated with increased readmissions and cost (

16). Therefore, length of hospital stay can be conceptualized as having both general medical and psychiatric determinants, which also may interact with each other. Treatment of the psychiatric determinants of increased length of stay may therefore be protective against one-year-subsequent health care costs.

We hypothesized that postdischarge mental health care would interact with length of stay such that costs in the subsequent year would be lower for patients with mental health needs when mental health care is provided.

Methods

This study identified a cohort of patients who used outpatient care and who had experienced a medical hospitalization but had no inpatient history in the prior year (N=21,716). Analysis variables were drawn from four time periods: the one-year period before admission, the inpatient stay, the 30-day period after discharge, and the subsequent year. Institutional review board approval was obtained from U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System.

Study setting and design

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest U.S. integrated health care system and is organized into 21 regional networks known as Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). This study analyzed health care costs and utilization among patients discharged from inpatient care for primary medical admissions in one VISN during fiscal year 2008.

Data sources and measures

Administrative VHA data were extracted for analysis: inpatient data, including length of inpatient stays as indicated in discharge files; outpatient visit information from a database of health care encounters; and cost data from the VHA bottom-up cost accounting system, which tracks health care costs at the individual level (

17). [The cohort is described further in an appendix included online as a data supplement to this article.]

Dependent variable

The primary dependent variable of interest was total cost (inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy costs combined) in the year after the 30-day postdischarge period and included direct costs, such as provider time, and indirect costs, such as overhead allocated to individual patient activities by an allocation mechanism (

17). Costs greater than $100,000 for inpatient (1.53% of patients), outpatient (.01%), and pharmacy (.34%) were each top-coded at $100,000 (1.8% total). Top-coding is a standard approach that minimizes the impact of idiosyncratic extreme levels of cost driven by utilization not well predicted by models (

18).

Independent variables

For each patient, independent variables were included for outpatient services received one year prior to the patient's admission date, characteristics of the inpatient stay, and in the 30 days postdischarge. Outpatient service utilization was categorized into primary care, medical specialty care, or mental health care services with an algorithm based on Current Procedural Terminology codes and provider type (

19).

Patient characteristics

Observed mental health diagnosis was determined with

ICD-9-CM codes (290, 293–302, and 306–316). Patients identified as having a reliably established mental health diagnosis were required to have two or more outpatient mental health diagnoses or one mental health diagnosis in the inpatient admission. Demographic characteristics included the patient's age, gender, and marital status; receipt of free care as a result of low income or disability; health status as measured by the presence or absence of a high-cost condition during the inpatient stay; and an index score based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index for outpatient care assessed one year preadmission and during the inpatient stay (

20). [Details are provided in the online appendix.]

Health care utilization

Outpatient specialty care utilization for the year prior to the inpatient stay was used as a proxy for differences in preadmission disease severity. Length of the inpatient stay was measured as a continuous variable. Thirty-day postdischarge utilization included the number of outpatient primary care and specialty care visits and dichotomous variables for readmission and mental health visits.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted with generalized linear models. We used SAS PROC GLIMMIX (SAS, version 9.1) to account for the nonnormal distribution of cost data. We conducted the modified Park test (

21) and Pregibon link test (

22) to determine the appropriate distribution and link functions to analyze the cost data. Models were initially estimated to adjust for clustering within inpatient facility, but the low percentage of variance accounted for by the facility level of analysis caused convergence problems, presumably because a small number of facilities were drawn from one geographical area.

A baseline model included all linear predictors. An interaction term between postdischarge mental health care and length of stay was then included in a second model. The interaction term was probed by estimating two models that would identify differences in the slopes of the independent variables with and without postdischarge mental health care. Other independent variables were included in all models.

Results

The results of the modified Park test supported a gamma distribution for total health care cost in the year after discharge, and the Pregibon test indicated that a log-link function was appropriate.

Patient characteristics and utilization

Postdischarge mental health care was provided for 3,275 of 21,716 patients (15%), with most receiving a single encounter in the 30-day period (N=2,158). Gender differences were observed in postdischarge mental health care (15% for men, N=3,016; 22% for women, N=259). Mental health diagnoses were reliably established in 38% of the sample, including 32% of patients who had no postdischarge mental health care. Only 71% (N=5,932) of the patients who received postdischarge mental health care had a prior mental diagnosis.

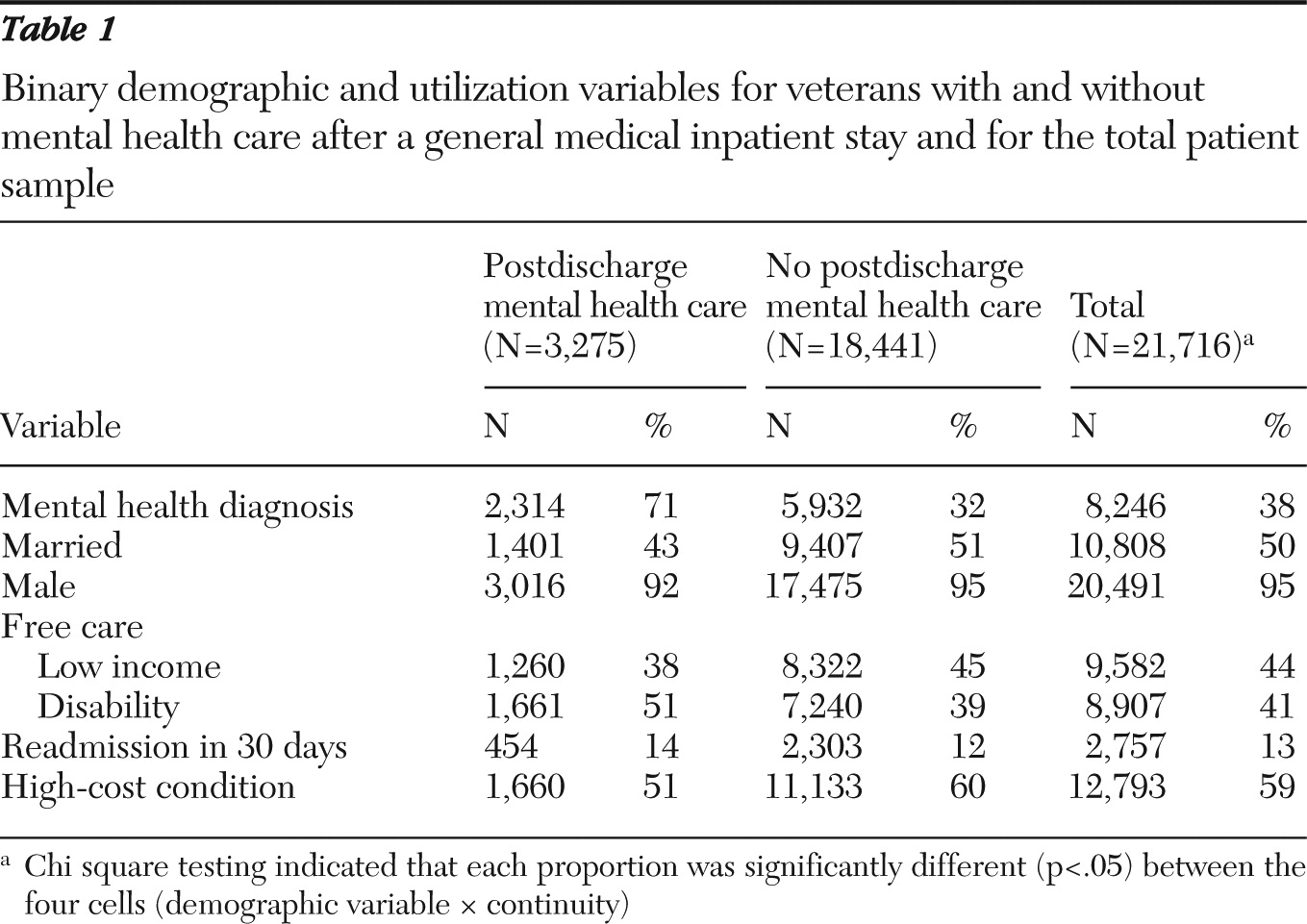

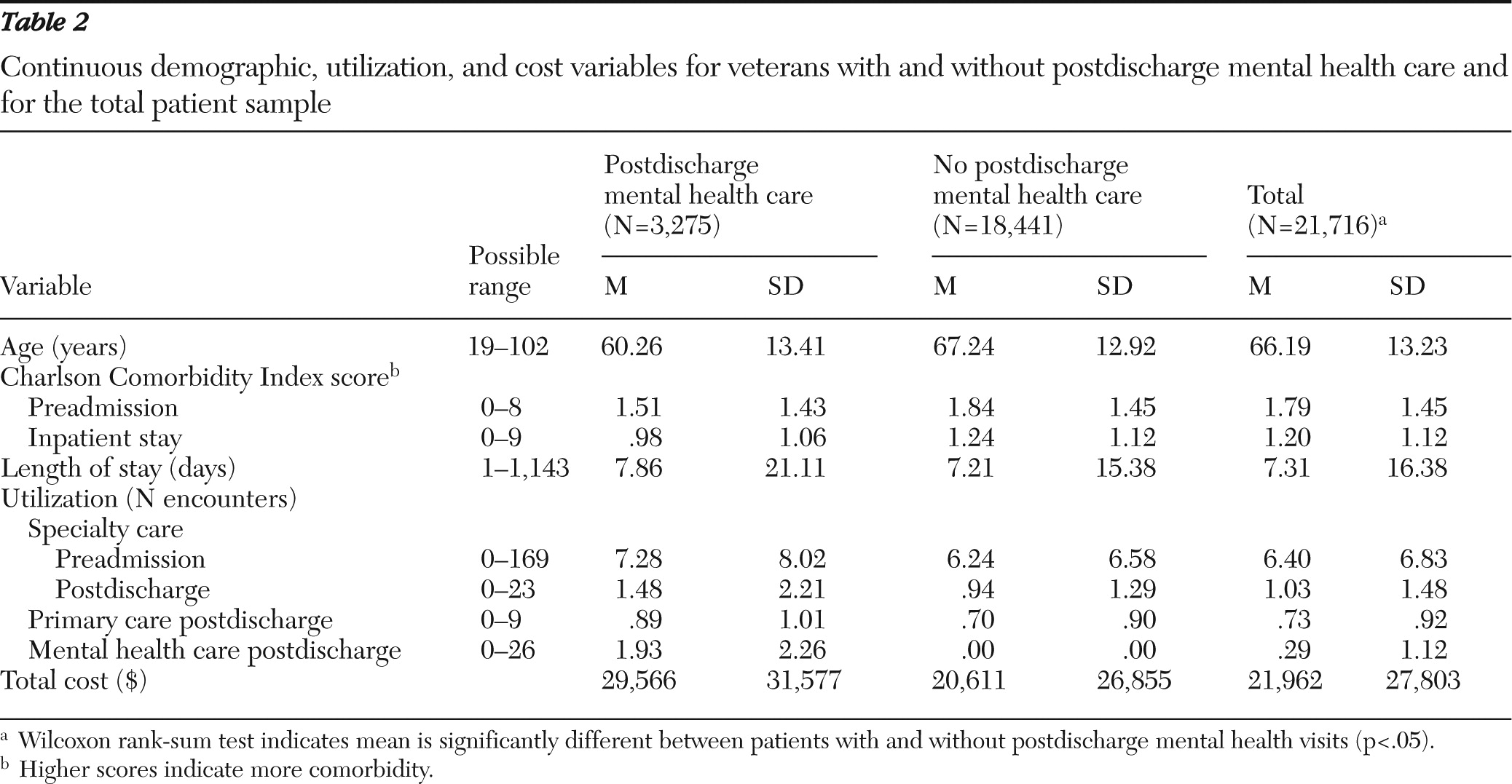

We conducted chi square tests for all binary demographic and utilization variables to test whether observed proportions differed by receipt of postdischarge mental health care (

Table 1), and similarly, we used Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for all continuous variables (

Table 2). Proportions significantly varied for all of the variables, partly because of the large sample sizes, which increase tendencies toward statistical significance of relationships. Notably, patients with postdischarge mental health care were more active users of outpatient care, both before and after hospitalization, than those without postdischarge mental health care.

Postdischarge mental health care and costs one year later

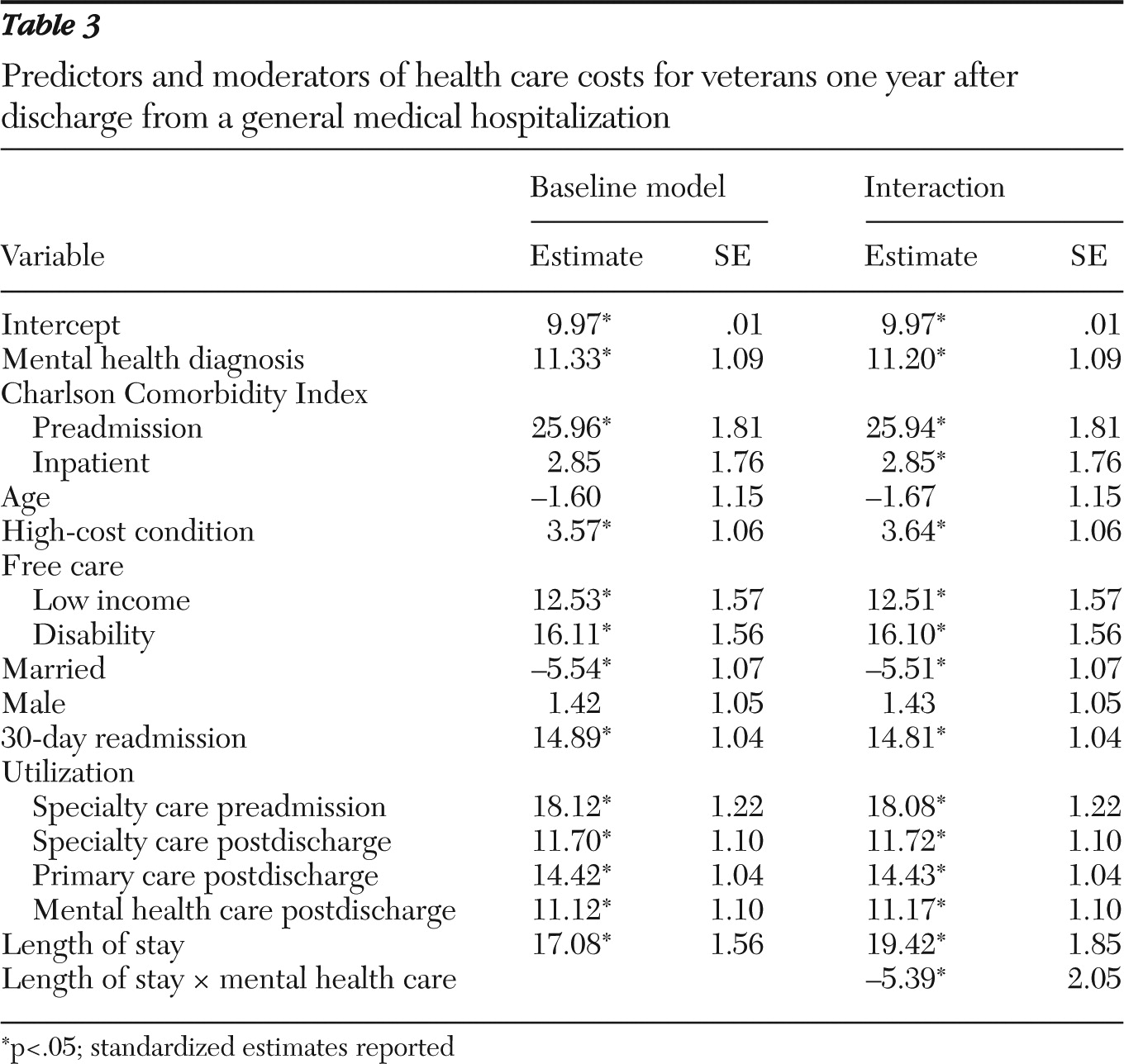

We tested whether postdischarge mental health care moderates the association of length of stay with health care costs one year postdischarge (

Table 3). We first estimated a baseline model with length of stay, postdischarge mental health care, and our patient-level demographic and utilization variables. We then estimated a model that included an interaction between length of stay and postdischarge mental health care. Most variables in both models were predictive of costs one year postdischarge, suggesting a well-specified model. The magnitude of the regression estimates was similar in both the baseline and interaction model, with a small increase in the regression estimate for length of stay. A significant negative relationship was observed between marital status and the one-year-subsequent costs, perhaps because married veterans are more likely to seek care outside the VHA system. Unexpectedly, the preadmission Charlson Comorbidity Index score was a significant predictor of one-year-subsequent costs, but the index score at inpatient admission did not demonstrate an independent association with costs one year later. Length of stay (

β=19.42) and postdischarge mental health care (

β=11.17) were each significantly (p<.05) and positively related to one-year-subsequent costs, and the interaction was significantly and negatively related (

β=–5.39, p<.05). These results indicate that postdischarge mental health care moderates the effect of the length of the medical inpatient stay on health care costs one year later.

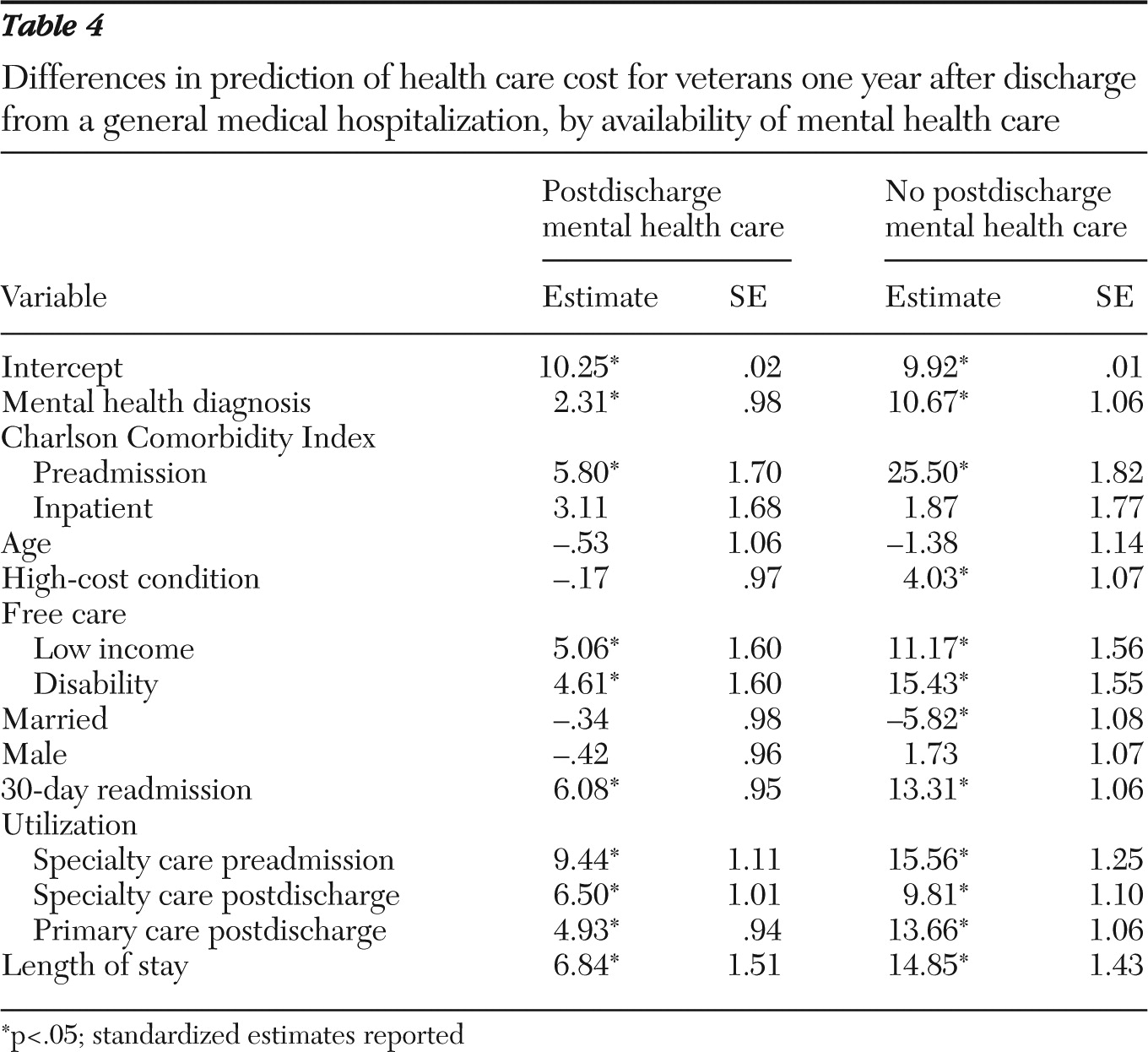

We probed the interaction between length of stay and postdischarge continuity of care by estimating one model without postdischarge mental health care and one model with mental health care (

Table 4). The intercepts were similar for both models, suggesting minimal differences in the average cost between the two samples. However, the magnitude of the standardized regression coefficient estimates for the group with no mental health care was generally more than twice the magnitude of the postdischarge mental health care group (

23).

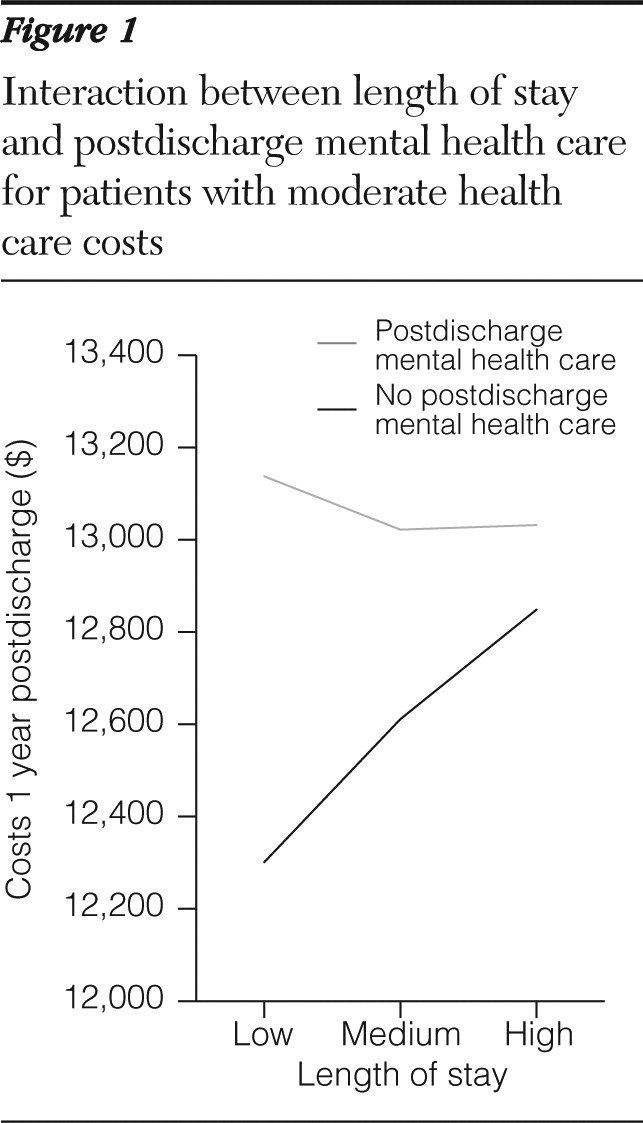

We further investigated the interaction between length of stay and postdischarge mental health care to determine clinical significance. Because both cost and length of stay were not normally distributed, we split the distributions of both variables into thirds and calculated mean cost for patients with and without postdischarge mental health treatment (18 cells; 2×3×3). We found that length of stay was negatively related to cost for low-cost conditions and positively related to cost for high-cost conditions. For moderate-cost conditions, length of stay was positively associated with costs for patients who did not receive mental health care but negatively associated with costs when postdischarge mental health care was provided, with no difference in costs between medium and high length of stay (

Figure 1).

Sensitivity analyses

We tested models with and without patients with diagnosed mental conditions before hospitalization. The interaction was significant only for the group with identified mental health conditions. We then conducted post hoc tests with the entire sample to determine whether nonhypothesized variables would demonstrate a significant interaction with postdischarge mental health care. Specifically, we calculated 95% confidence intervals for both populations and determined the difference between the upper bound of the postdischarge mental health care population and the lower bound of the population with no mental health care. We selected variables that demonstrated differences between the two populations that were greater than that observed for length of stay. Significant interactions were observed between postdischarge mental health care and each of the following three variables: recorded mental health diagnosis (β=−4.23, SE=2.11, p<.05), free care due to disability (β=−3.32, SE=1.53, p<.05), and preadmission Charlson Comorbidity Index (β=−2.99, SE=1.18, p<.05). Significant interactions were not observed for postdischarge primary care utilization (p=.08) or 30-day readmissions. Finally, we estimated a model [see online appendix] with each of the interaction terms included. These results support the hypothesis that postdischarge mental health care is broadly important for limiting health care costs one year later.

Discussion

This article presents a methodology to analyze the effect of mental health treatment in the 30 days after hospital discharge for a general medical issue on subsequent health care utilization. We focused on general medical hospitalization discharges and costs, but these could be extended to psychiatric discharges and other utilization-related outcomes (such as readmissions). Postdischarge mental health care was found to moderate the association between length of inpatient stay and postdischarge costs such that mental health care reduced the one-year health care costs associated with length of stay. Postdischarge mental health care was shown to be most important for patients with moderate levels of subsequent cost, a proxy for disease severity. We found that the interaction was not significant for the population that did not have reliably established mental health diagnoses before admission, which was likely a result of the low frequency of patients with unidentified mental conditions relative to patients with no mental health needs. Results suggest that hospitals could benefit from screening all inpatients for psychiatric problems and ensuring that patients with positive screens receive postdischarge mental health care. Results indicate that providing mental health care postdischarge for patients who require it is protective against the increased cost associated with comorbid mental conditions.

Our conceptual framework focused on inpatient admissions with no hospitalizations in the prior year in order to complement current research on transitions of care and preventable readmissions (

8,

24). Previous work showing an extremely strong relationship between mental health conditions and readmissions unrelated to mental health condition focused on patients with an active history of multiple admissions (

10). This study extends this prior research by focusing on costs one year after discharge in a population without a recent inpatient history before the index general medical admission. Thus postdischarge mental health visits appear to be broadly important for patients receiving inpatient care. We recognize that mental health care increases health care costs, although the results suggest that these utilization-based costs can be investments in subsequent patient health.

The intent of this exploratory study was to motivate future research to determine how to structure mental health care associated with general medical treatment such that subsequent costs can be minimized. This study was not designed to reach a definitive conclusion regarding the appropriate response to a new inpatient medical admission. Rather, we intended to promote further research on both understanding the mental health implications of inpatient general medical care and developing systems to reduce the impact of these admissions for patients with mental health needs. Finding ways to ameliorate long-term costs arguably is the most important deep-seated problem in the health care system today.

This study had several limitations. We restricted our analyses to active users of outpatient care, but not inpatient care, in order to minimize the number of veterans seeking non-VHA postdischarge care not measured here, but the impact of general medical hospitalizations may be more severe for patients who do not regularly attend primary care appointments. We also included all medical diagnoses and procedures in our analyses rather than selecting a specific medical diagnosis. This heterogeneity may have attenuated effects, in that some conditions, such as cancer, may be more likely to require postdischarge mental health treatment, so further work could investigate impacts in particular disease areas. Similarly, we chose to include patients without reliably identified mental health conditions to ensure that we did not exclude the 29% of patients who received postdischarge mental health care without a mental health diagnosis. We also did not distinguish between diagnosed mental disorders by severity or type. Results suggest that postdischarge mental health care is broadly important for patients with mental health needs, but it is unclear whether effects apply both to common conditions such as depression or anxiety and to severe conditions such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Further, the mental health needs of the VHA population are not the same as those of the private sector. VHA provides motivation in its system to treat serious mental illnesses (such as schizophrenia) that might otherwise remain untreated or be concentrated within public insurance programs. We might expect that undiagnosed or uncoded mental illness among veterans is lower than occurs in other populations.

We note a fallacy in the causal logic in our analysis of clinical significance, in that we stratified our analyses by values of the dependent variable. Stratification was necessary because costs were not normally distributed, but it confounds interpretation. Generally, causality should not be inferred from our results. We tested a longitudinal model with a health care intervention (that is, inpatient treatment), but there was no random assignment to treatment conditions. Endogeneity is broadly a concern in our model because factors that promote utilization before admission may affect utilization postdischarge. For example, our selection criteria restricted our sample to patients with high primary care utilization and therefore restricted the range of postdischarge primary care utilization. This range restriction is likely one reason why we did not detect a significant interaction between mental health care and primary care utilization postdischarge. Therefore our study at most constitutes a quasi-experimental design aimed at generating hypotheses regarding the role of postdischarge mental health treatment for discharged general medical inpatients and at promoting further research that might point toward interventions. Current research on care transitions (

8,

25,

26) could perhaps be augmented by closer attention to mental health coordination issues. Primary care could be an ideal setting to conduct postdischarge mental health screening as part of care transitions. As part of a broad effort to implement integrated mental health care in the primary care setting, VHA has recently instituted mental health screening procedures in primary care clinics (

27). It is unclear whether VHA inpatients are being prioritized for postdischarge primary care appointments, and there is mixed evidence regarding the role of mental health care in postdischarge transitions. One recent study has shown that providing mental health care in the primary care setting is associated with lower ambulatory care-sensitive hospitalizations (

28). Other research has shown that patients with positive screens for mental health conditions are at an increased risk of readmissions (

12). Future research should incorporate mental health screening (for example, with the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire) for cohort identification.

Conclusions

We have presented a novel framework whereby general medical hospitalizations are proposed to affect costs of care one year later. We identified postdischarge mental health care as a mechanism to reduce the impact of general medical admissions by treating the psychiatric determinants of variation in length of inpatient stay. This study points to the need for future research on identifying the cost implications of inpatient medical care one year postdischarge, developing interventions to minimize the impact of inpatient stays on future health care use, and understanding the implications of mental health conditions for one-year-subsequent outcomes of general medical hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Financial support was provided in part by grant IIR 08-067 from U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) and by a VA Office of Academic Affiliations HSR&D postdoctoral fellowship. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VA or the U.S. government. The authors gratefully acknowledge the editorial contributions of Michael Shwartz on the manuscript.

The authors report no competing interests.