Although most people with mental illness are not violent, they are at greater risk of violence than the general population (

1–

3). In settings such as psychiatric inpatient units and emergency rooms, violence is a common problem that is a frequent cause of injuries to clinicians (

4–

6). Trainees in psychiatry, clinical psychology, and other mental health disciplines often complete rotations in these acute settings and are especially vulnerable to being victims of patient aggression (

7–

10).

Credentialing organizations and the public expect psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and other mental health professionals to have competency in violence risk assessment (

11,

12). Yet surveys show that clinical trainees often report that their education is insufficient in the area of violence risk assessment and management (

13–

15). Moreover, there is surprisingly little scientific evidence that training and experience confer an advantage in the ability to assess patients’ risk of violence. In fact, one widely cited study challenged this assumption. Quinsey and Ambtman (

16) provided case files to a group of experienced forensic psychiatrists and a group of high school teachers and asked them to evaluate the likelihood that the patients would become violent; the results suggested that the reliability and validity of judgments by the two groups did not differ. Although the study raised important issues, the generalizability of its conclusions may be limited by use of case files rather than live clinical encounters. Research is lacking on whether, in the course of service delivery to patients, highly trained and experienced clinicians are more accurate in violence risk assessments than those with little training. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate that issue.

If trainees are indeed less able than trained and experienced clinicians to accurately perform risk assessments for violence, it is important to consider ways to improve their accuracy. One promising strategy is to educate them in structured methods. In recent years, a variety of structured risk assessment measures have been developed that have the potential to improve violence risk assessments by prompting clinicians to consider patient characteristics supported by research as risk factors for violence (

17,

18). That is, these measures are evidence-based decision aids. One such tool, the Historical, Clinical, Risk Management–20 (HCR-20), asks the evaluator to consider historical, clinical, and situational variables linked to violence potential (

19). Many studies have supported the validity of the HCR-20 as an aid to violence risk assessment (

20–

22). Even though accumulating research supports the predictive validity of structured methods of violence risk assessment, these validated measures are relatively new and are only beginning to be adopted in many areas of clinical practice (

21,

23). A secondary goal of this study was to explore the potential of a structured risk assessment instrument to improve the predictive validity of trainees’ risk assessments.

This study addressed the following questions on the basis of reviews of medical records of a sample of hospitalized patients. First, were the violence risk assessments that had been completed at the time of admission by attending psychiatrists more accurate than those that had been completed by psychiatric residents? Second, would addition of information from the HCR-20 improve the accuracy of risk assessments above that of residents’ unstructured clinical evaluations of violence potential?

Methods

The study employed a retrospective, case-control design. The protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco.

Participants and setting

The setting was the four locked psychiatric inpatient units of a county hospital that serves a city of approximately 750,000 residents. We reviewed incident reports of all unduplicated patients (N=172) who had physically assaulted staff between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2008. For patients who had more than one incident of violence, only the first incident was considered. To verify the severity of the episodes of aggressive behavior, descriptions of the episodes in the incident reports and medical records were rated by two doctoral-level mental health clinicians (AT and SH) using a standardized measure of inpatient aggression, the Staff Observation Aggression Scale–Revised (SOAS-R) (

24). The interrater reliability of these ratings was high (κ=.93). The mean±SD SOAS-R total score was 17.3±2.3, well above the threshold for severe aggression of 9.0 recommended by an author of that scale (

25).

After matching for psychiatric inpatient unit and month of admission, 173 nonviolent comparison patients were selected by using a table of random numbers generated by Excel. Data were excluded for 21 of the violent patients and 23 of the nonviolent patients because their medical records did not include information about level of training of the physician who completed the admission risk assessment. The final sample included 151 violent patients and 150 nonviolent patients.

Clinical risk assessment ratings

At admission, physicians had rated each patient on a 4-point assault precaution checklist that ranged from 0, no clinical indication for precautions, to 3, strong intent is present or unable to control impulses. For each patient, only one clinician made an assessment of violence risk.

Thirty-eight psychiatry residents rated 52 patients. The mean± SD length of residency training for this group was 1.2±1.0 years; their mean age was 30.7±2.5 years. The mean number of patients rated by each resident was 1.4±.7, with a range of one to four patients. Forty-one attending psychiatrists rated 249 patients. The mean length of postresidency experience for this group was 13.7±7.1 years (based on data available for 199 of the 249 patients); the mean age of the psychiatrists was 46.8±7.5 years. The mean number of patients rated by each attending psychiatrist was 6.1±8.3, with a range of one to 34 patients.

Structured risk assessment ratings

The HCR-20 clinical subscale (HCR-20-C) (

19) was used to rate charts for acute risk of violence. The clinical subscale includes five items (active symptoms of major mental illness, impulsivity, lack of insight, negative attitudes, and unresponsive to treatment) that are rated on a 3-point scale: 0, absent; 1, possibly present; and 2, present. The clinical scale was selected for use on the basis of previous research evidence that it has a stronger association with short-term risk of aggression by acute psychiatric inpatients than the other components of the HCR-20 (

26,

27). Several previous studies have rated HCR-20 items on the basis of record review (

26–

28), although interviews may also be used to supplement file information.

In this study, two psychiatric nurses, who had been trained in the use of the measure, rated the HCR-20-C based on information that was available in the medical records at the time of admission. The two raters were blind to whether the patients later became violent. Their interrater agreement, as measured by the intraclass correlation coefficient was .78 on eight practice charts and .81 on a sample of 43 of the 301 study participants (14%).

Data analysis

To characterize the sample, comparisons of whether patients evaluated by residents and attending psychiatrists had different demographic and clinical characteristics were conducted using chi square analyses for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables.

The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was used to assess the predictive validity of the risk assessments (

29,

30). ROC analysis describes predictive accuracy across a range of cutoff scores and is less dependent on the base rate of violence than conventional approaches. The AUC represents the probability that a randomly selected violent patient will have been evaluated by the risk assessment method as being at higher risk than a randomly selected nonviolent patient. The AUC can range from 0, perfect negative prediction, to 1, perfect positive prediction; an AUC of .5 represents accuracy no better than chance. As a general rule, the predictive validity of AUCs of .80 to .90 is considered excellent, .70 to .79 is acceptable, and .60 to .69 is modest (

31). The AUC for patients evaluated by residents was compared with the AUC for patients evaluated by attending psychiatrists with a Wald test for the difference in AUCs for two independent groups (

29).

To address the secondary research question regarding the potential of the HCR-20-C to improve predictive accuracy over and above residents’ unstructured clinical risk assessments, we performed incremental validity analyses following a method previously described (

32). Specifically, we performed two linear regression analyses whereby the clinical risk assessment ratings were used to predict the HCR-20-C scores and the HCR-20-C scores were used to predict the clinical risk assessment ratings. The residuals from these analyses represent the unique independent variance of each measure beyond that of the other (that is, the variance of the clinical risk assessment independent of the HCR-20-C and vice versa). We then conducted ROC analyses based on these residuals.

Data were analyzed with SAS, version 9.2; Stata, version 10; and PASW, version 18.

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, the study group was ethnically diverse and middle-aged, with a larger proportion of men than women (

Table 1). Most patients had psychotic disorders. No significant differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were found between patients assessed by residents and those assessed by attending psychiatrists. Similarly, the proportion of patients who later became violent in the hospital did not differ significantly by whether residents or attending psychiatrists conducted the assessments.

Relationship between level of training and accuracy

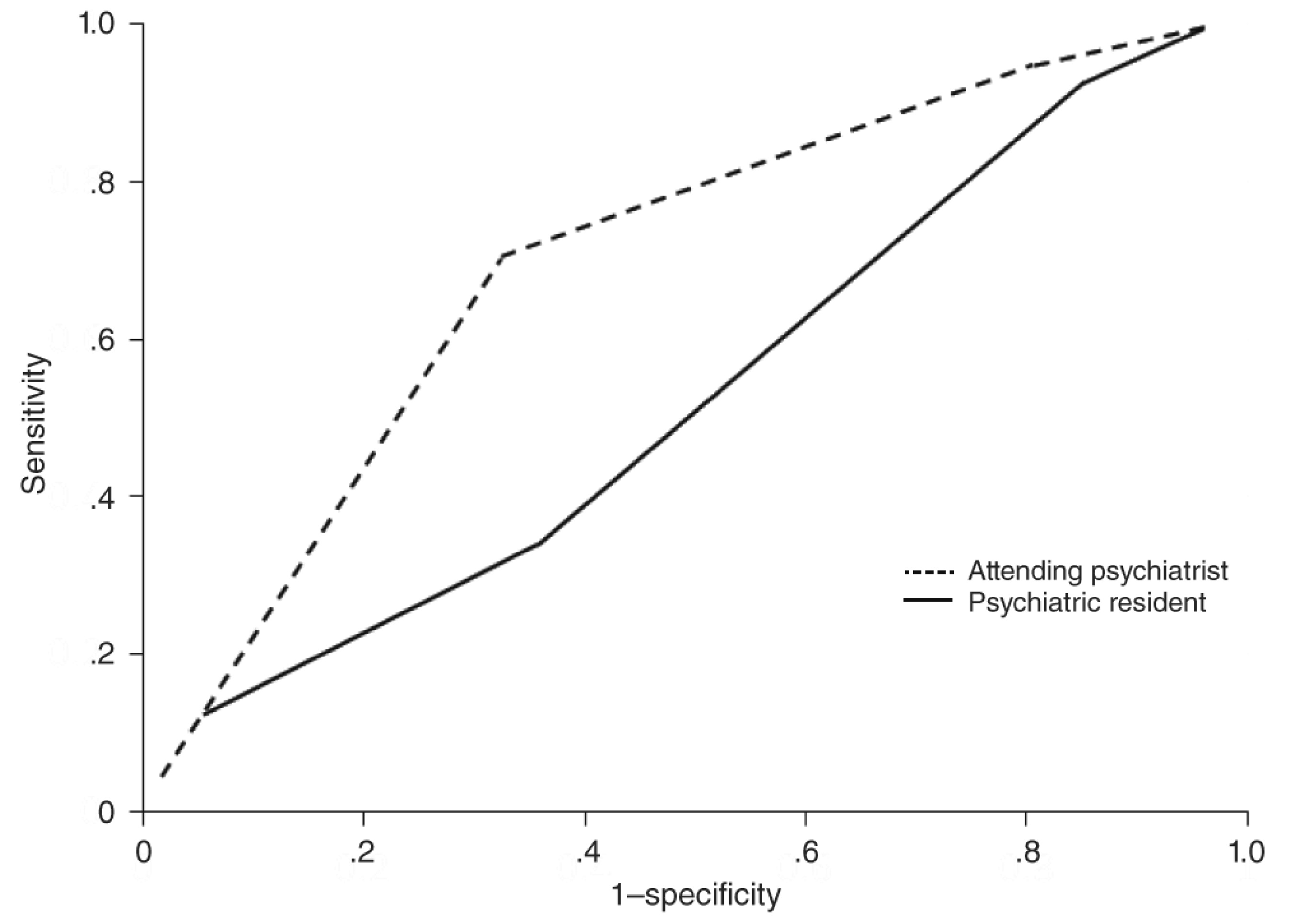

As shown in

Figure 1, clinical risk assessments by attending psychiatrists had a moderate degree of predictive validity (AUC=.70), whereas those completed by residents were no better than chance (AUC=.52). The risk assessments by attending psychiatrists were significantly more accurate than those by residents (χ

2=5.52, df=1, p=.02).

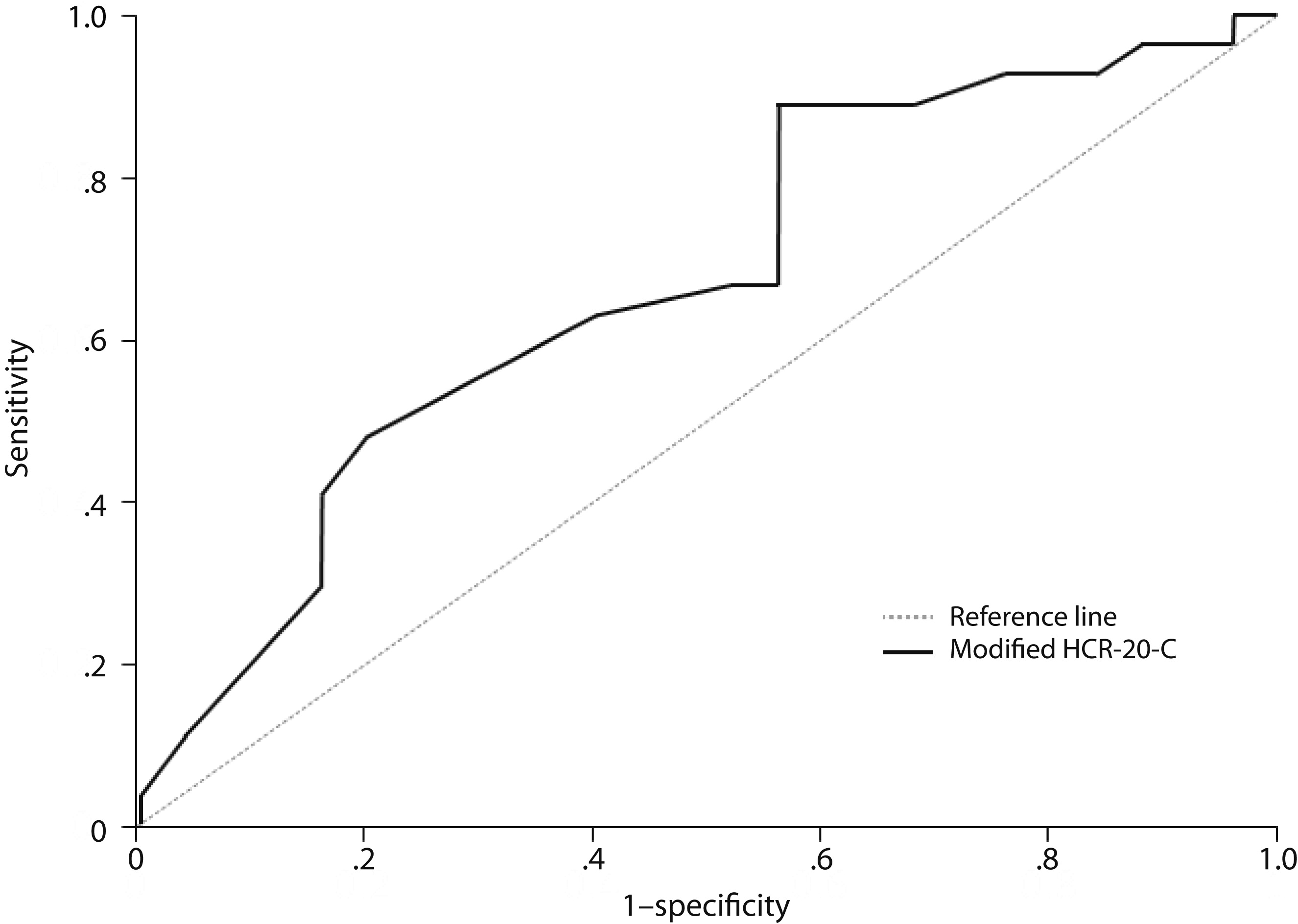

Incremental validity of the HCR-20-C

For patients evaluated by residents, the AUC of the HCR-20-C was .60 (SE=.08). ROC analysis of the residuals showed that the AUC for the variance attributable to the clinical risk estimates independent of the HCR-20-C was only .55 (SE=.08), whereas the variance attributable to the HCR-20-C independent of the clinical risk estimates was more strongly associated with violence (AUC=.67, SE=.08).

Figure 2 illustrates the application of the HCR-20-C to the patients evaluated by psychiatric residents.

It is of interest that the AUC of the HCR-20-C independent of the residents’ clinical risk estimates (.67) was similar to the AUC of the clinical risk estimates of the attending psychiatrists (.70). This suggests that adding information from the HCR-20-C to residents’ evaluations has the potential to bring the accuracy of their risk assessments close to that of more experienced attending psychiatrists.

For the patients evaluated by attending psychiatrists, the AUC of the HCR-20-C was .69 (SE=.03). Incremental validity analysis showed that the AUC for the variance attributable to the attending psychiatrists’ clinical risk estimates independent of the HCR-20-C was .65 (SE=.04), whereas the variance attributable to the HCR-20-C independent of the attending psychiatrists’ clinical risk estimates was limited (AUC=.57, SE=.04). Hence, for patients evaluated by attending psychiatrists, the HCR-20-C yielded little incremental validity over that of the unstructured clinical risk estimates.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the predictive validity of assessments of violence risk by experienced clinicians to those made by trainees in a clinical setting. The results support the conclusion that level of training is associated with greater accuracy of violence risk assessment. Whereas the risk assessments of highly experienced attending psychiatrists demonstrated a moderate degree of predictive validity, those of a group of junior psychiatric residents—who evaluated patients with similar characteristics—were no better than chance.

This study has implications for training and education regarding violence risk assessment. First, it highlights the importance to clinical training programs of education in violence risk assessment (

33–

37). Second, it provides further evidence that structured methods hold promise as an aid to development of skill in risk assessment. Previous research has shown that when trained in the HCR-20, psychiatric residents and learners from other backgrounds demonstrate improved clinical reasoning about violence risk, as evidenced by improved documentation of case formulations and intervention plans (

38,

39). This study showed that adding information from the HCR-20-C has the potential to improve trainees’ risk assessments to a level of predictive accuracy similar to that of experienced attending psychiatrists. Information needed to rate the HCR-20-C is routinely collected in the course of admitting patients to a psychiatric inpatient unit, and prompting trainees to rate this structured measure could help them to attend to valid risk markers from among the vast amount of information that may become available during the course of an admission workup. Third, improvements in accuracy offered by use of a structured risk assessment tool can guide development of interventions to prevent violence (

40).

A strength of this study is its external validity. First, because of the large sample of attending psychiatrists and residents, results are more likely to be generalizable. Second, the ecological validity of the study is enhanced by its evaluation of the outcome (violence) in a clinical setting undisturbed by the predictor variables (type of risk assessment method and level of training). Limitations of the study include that it was conducted in one site and relied on retrospective chart review. Use of incident reports to identify violent incidents may not have been sensitive to milder forms of patient aggression. It is possible that the predictive validity of the HCR-20-C would have differed if the patients had been rated and followed prospectively. Also, the generalizability of the findings beyond the inpatient setting remains a topic for future research.

Conclusions

This study addressed an important gap in the field of violence risk assessment related to the relationship between level of training and accuracy of violence risk assessment. The results support the conclusion that level of training confers an advantage in the accuracy of risk assessments for violence. In addition, the results illustrate that structured methods have the potential to augment training in a way that may improve the accuracy of risk assessments.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was partly supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant R25 MH060482), a Minority Fellowship sponsored by the American Psychiatric Association and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR024131) from the National Institutes of Health.

The authors report no competing interests.