Older adults are more likely to visit a primary care physician for a behavioral health problem, and younger adults are more likely to seek help from a behavioral health specialist (

1–

5). Although service use may change with age, cohort differences have been found in both the prevalence of disorders and service use (

6–

8). These cohort differences are believed to persist even as changes occur with aging. Combined with the expected growth in the number of older adults overall, this finding suggests an increased need for physical and behavioral health services appropriate for older adults (

9–

13).

However, beyond documenting the greater use of primary care physicians, few studies have examined the combinations of service providers visited for behavioral health issues and how those combinations may vary by service users’ age. By developing typologies of service providers visited and grouping individuals reporting similar patterns, latent class analysis is a useful tool for examining the complexity and multidimensionality of service use (

14). Studies that have taken this approach have contributed to a more nuanced understanding of service use that moves beyond classifications of users versus nonusers and focuses on identifying and describing subgroups of individuals. Such approaches can inform efforts to tailor interventions, outreach, and policy and facilitate the timely and effective use of behavioral health care.

For example, Choi and colleagues (

15) identified three clusters of service use among older adults with severe depression. These clusters shed light on subgroups of this sample who used combinations of home-based supportive services for functional needs and outpatient behavioral health services to maintain their life in the community. Carragher and colleagues (

16) examined three classes of service use for major depression (highly active, partially active, and inactive). Adults 65 and older were more likely to fall in the partially active class, members of which consulted a professional and received prescriptions for medication but had not been hospitalized or visited an emergency department for depression.

This study adds to this body of work in two ways. First, latent class analysis was used with nationally representative survey data to examine patterns of service providers visited for a behavioral health problem. Second, it examined how those patterns differ by age of service user.

Results

Compared with the younger adults, a higher proportion of the older adults was female and previously married (

Table 1). Older adults were slightly less diverse by race-ethnicity and had fewer years of education. In contrast to the younger group, a majority of older adults were not in the labor force and had public health insurance coverage, and a higher proportion was in the lower two income quartiles. Fewer older adults met criteria for behavioral health disorders, whereas a higher proportion reported having general physical disorders. Compared with younger adults, a higher proportion of older adults visited a family or other physician for a behavioral health disorder. A higher proportion of the younger age group visited most other types of professionals.

Results of fitting latent class models

A five-class solution was chosen according to measures of model fit and because it was most conceptually meaningful.

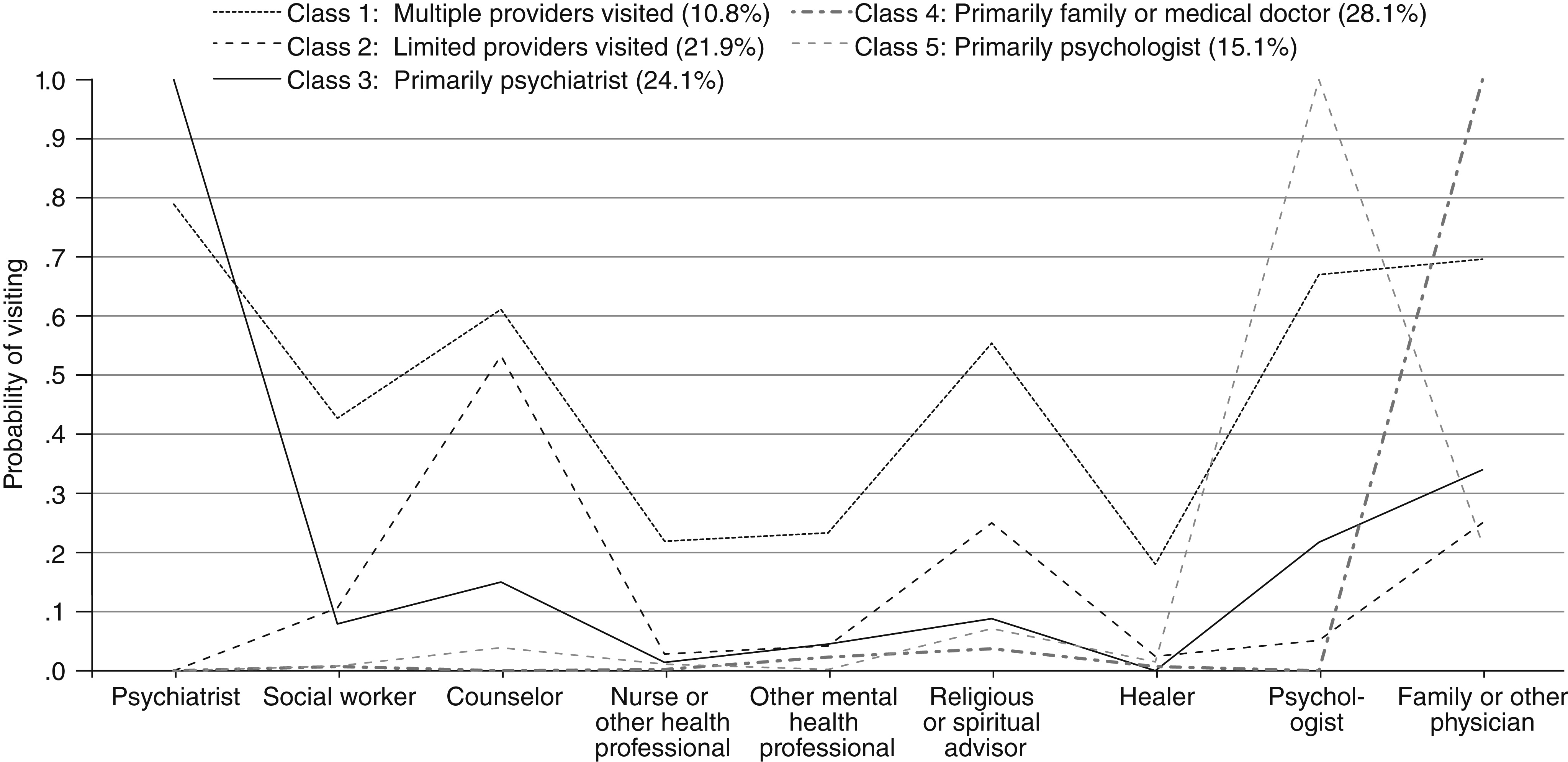

Figure 1 depicts the prevalence of each class and the predicted probability that service users assigned to a class would visit those specific service providers. Class 1, labeled “multiple providers visited,” contained 10.8% (N=419) of the respondents. Members of class 1 had a high probability of visiting a psychiatrist (.789) and a moderate probability of visiting a social worker (.427), a counselor (.611), a religious or spiritual advisor (.554), a psychologist (.670), or a family physician or other physician (.696). Members of this class had a low probability of visiting a nurse or other health professional (.219), another mental health professional (.233), or a healer (.180). Overall, members of class 1 had a moderate to high probability of visiting six out of nine types of providers.

Class 2, labeled “limited providers visited,” contained 21.9% (N=878) of the respondents. Members of this group did not have a high probability of visiting any of the providers and had a moderate probability of visiting a counselor (.533). There was a low probability of visiting all other providers (≤.25) and no probability of visiting a psychiatrist. The defining characteristic of this group was low probability of visiting most providers.

Class 3, labeled “primarily psychiatrist,” contained 24.1% (N=1,093) of respondents. Members of this class had 100% probability of visiting a psychiatrist but low probability (≤.34) of visiting all other types of providers.

Class 4, labeled “primarily family physician,” contained 28.1% (N=1,128) of respondents. Members of this class had 100% probability of visiting a family physician or other physician and very low probability (≤.037) of visiting other professionals, including no probability of visiting a psychiatrist, counselor, or psychologist.

Finally, class 5, labeled “primarily psychologist,” contained 15.1% (N=564) of respondents. Members of this class had 100% probability of visiting a psychologist and low probability (≤.214) of visiting other types of providers, including no probability of visiting a psychiatrist.

Demographic and psychiatric predictors of class membership

The largest proportion of older adults (41.9%) was in the primarily family physician class, followed by primarily psychiatrist (25.8%), limited providers visited (13.5%), primarily psychologist (11.8%), and multiple providers visited (7.0%). Those in the younger age group were more evenly distributed, with roughly a quarter in the limited providers visited (26.1%), primarily psychiatrist (23.2%), and primarily family physician (21.2%) classes. Seventeen percent fell into the primarily psychologist class, and 12.8% fell into the multiple providers visited class (Rao-Scott χ2=38.07, df=4, p<.001).

Multinomial logistic regression was used to assess sociodemographic and disorder-related predictors of class membership, with the primarily family physician class as the reference category (

Table 2). Older adults and women were less likely than the younger age group and men to be in every class compared with the primarily family physician class. Those who were previously married were more likely than those who were currently married to be in the limited providers class, whereas those who were previously or never married were more likely to primarily visit psychiatrists. More years of education was associated with a greater likelihood of being in every class compared with the primarily family physician class. Those who were unemployed were significantly more likely to be in the class that primarily visited psychiatrists, whereas those not in the labor force were more likely to visit multiple providers. Respondents with an anxiety disorder were less likely to be in the class that visited a limited number of providers, whereas those with a substance use disorder were more likely to have visited multiple providers or primarily psychiatrists. Compared with respondents who did not meet criteria for a behavioral health disorder, those with one disorder were more likely to be in the class with limited providers visited, whereas those with two or more disorders were more likely to have visited multiple providers or a limited number of providers.

Analyses of interactions of age with other demographic variables indicated that older black Caribbeans were more likely than persons of other racial or ethnic groups to have visited a limited number of providers and to have visited primarily a psychiatrist (

Table 3). Older adults who were not in the labor force, had public insurance coverage, or had no insurance coverage were less likely than younger adults to have visited multiple providers. Older adults with public insurance were also less likely to be in the classes with limited providers visited or visits primarily to psychiatrists. Older adults in the middle household income categories were more likely to be in the class that primarily visited psychologists, whereas those with incomes between $40,000 and $73,498 were also more likely to visit multiple providers.

Discussion

Consistent with previous research, this study indicated that when faced with a behavioral health problem, older adults relied heavily on a family physician or other physician within the general medical sector (

1–

5). Furthermore, older adults were more likely than the younger age group to rely primarily on a family physician compared with every other class of provider, suggesting that baby boomers visited a broader range of providers. Although it is not possible to disentangle aging from cohort effects with these cross-sectional data, previous research with longitudinal data has found age cohort differences in service use that have remained significant over time, suggesting the possibility that differences found in this study may continue with age (

6). It is reasonable to expect that the use of the general medical sector will increase as baby boomers encounter more general health problems with age. However, cohort-specific cultural and social differences, such as a greater acceptability of reporting and seeking treatment for behavioral health problems, may continue to influence service use patterns (

7,

24).

Efforts have been made to integrate behavioral health treatment into primary care with the explicit objective of improving treatment for older adults (

25,

26). Findings from this study support the continued importance of these efforts. Almost half of the younger age group (46.7%) reported visiting a family physician or other physician for a behavioral health problem, and 21.0% were in the primarily family physician class. Primary care physicians clearly play an important role in behavioral health care. Additional research is needed to clarify whether visits to different providers occur simultaneously or concurrently and the gateways through which individuals enter services, as well as patterns of referral and the extent to which treatment is coordinated across service providers. However, this study reaffirmed the importance of ongoing efforts to better connect behavioral and general medical care.

Several other differences by age are worthy of note. Although insurance coverage did not have a main effect on class membership, older adults with public insurance coverage were less likely than the younger group to fall into three of the five classes. One possible reason for this is that Medicare, the public insurance by which most older adults are covered, does not cover services from many of the other providers considered in this study. Second, those in the younger group were more likely to be covered by Medicaid, which is need based, whereas Medicare is universal for those ages 65 and over. Unfortunately, the data did not allow differentiation of insurance coverage at this level, limiting the ability to separate age differences from differences in coverage or to examine some of the complexities of coverage, such as dual eligibility for both Medicare and Medicaid.

Although there were few racial-ethnic differences overall, older black Caribbeans were more likely to be in the class that visited a limited number of providers. Previous studies have found that persons from racial-ethnic minority groups are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to use the general medical sector rather than specialty care for a behavioral health problem (

1–

3,

27,

28). Overall, this study suggests that, among service users, when a range of service providers is considered, the relationship between race-ethnicity and where people go for help is more nuanced. It also highlights the importance of considering within- as well as between-group differences. Black Americans are often treated as a homogeneous group, although blacks of Carribean descent and African Americans differ in terms of ethnicity, national heritage, socioeconomics, and immigration status (

29). In combination with other recent studies, these findings highlight the importance of looking further at within-group heterogeneity (

2,

30,

31). Such complexities may influence treatment outcomes and pathways into and out of care.

The effect of employment status on class membership was also moderated by age. For the sample as a whole, not being in the labor force was associated with visiting multiple providers. However, older adults who were not in the labor force were significantly less likely to fall into this class. This may in part be due to individuals’ reasons for not being in the labor force. Among the younger age group, for example, those not in the labor force were more likely to have multiple disorders compared with those who were employed or unemployed, suggesting an association between severity of disorders and work status. Older adults, over half of whom were not in the labor force, may be in retirement.

One major limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the data. For this reason, it was not possible to determine the extent to which respondents visited service providers simultaneously or serially nor how the combinations of service providers visited may have changed over time. Cross-sectional data also limit the ability to differentiate cohort versus aging effects as described above. Furthermore, these data were collected between 2001 and 2003. Over the past decade, significant changes have occurred in the financing and delivery of behavioral health services, including the increased use of managed care and behavioral health parity legislation (

32,

33). Previous studies suggest that parity in behavioral health care coverage can increase the use of appropriate services (

33); however, research has not examined the influence of systemic changes on the types of providers visited. With time, we will learn whether perceived cohort differences suggested by this and other research remain in the face of such structural changes.