Less than one-quarter of children with a psychiatric disorder have contact with specialized services (

1). Even among adolescents with severe disorders only about half have used mental health services during their lifetime (

2). For service system planning, it is important to know the patterns of service use; for example, at what age do children enter the service system, for how long do they use services, what is the sex distribution, what are the common diagnoses, and which diagnoses overlap? However, because of methodological issues, there is a lack of reliable information to answer these questions.

Longitudinal population-based studies of information obtained in interviews have described the longitudinal course of common developmental psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and conduct disorders (

3,

4), but their sample sizes were not large enough to study service use of less frequently diagnosed but clinically important disorders, such as autism spectrum disorders. In fact, it has been proposed that an approach other than a survey is needed for studying relatively rare but clinically important disorders (

5). Large cross-sectional studies with information from questionnaires or registers can be used when calculating service use prevalence during one year, but when calculating lifetime estimates, longitudinal data sets are preferable to cross-sectional data because of recall bias (

6). When studying longitudinal service use patterns, register-based data are especially valuable (

7).

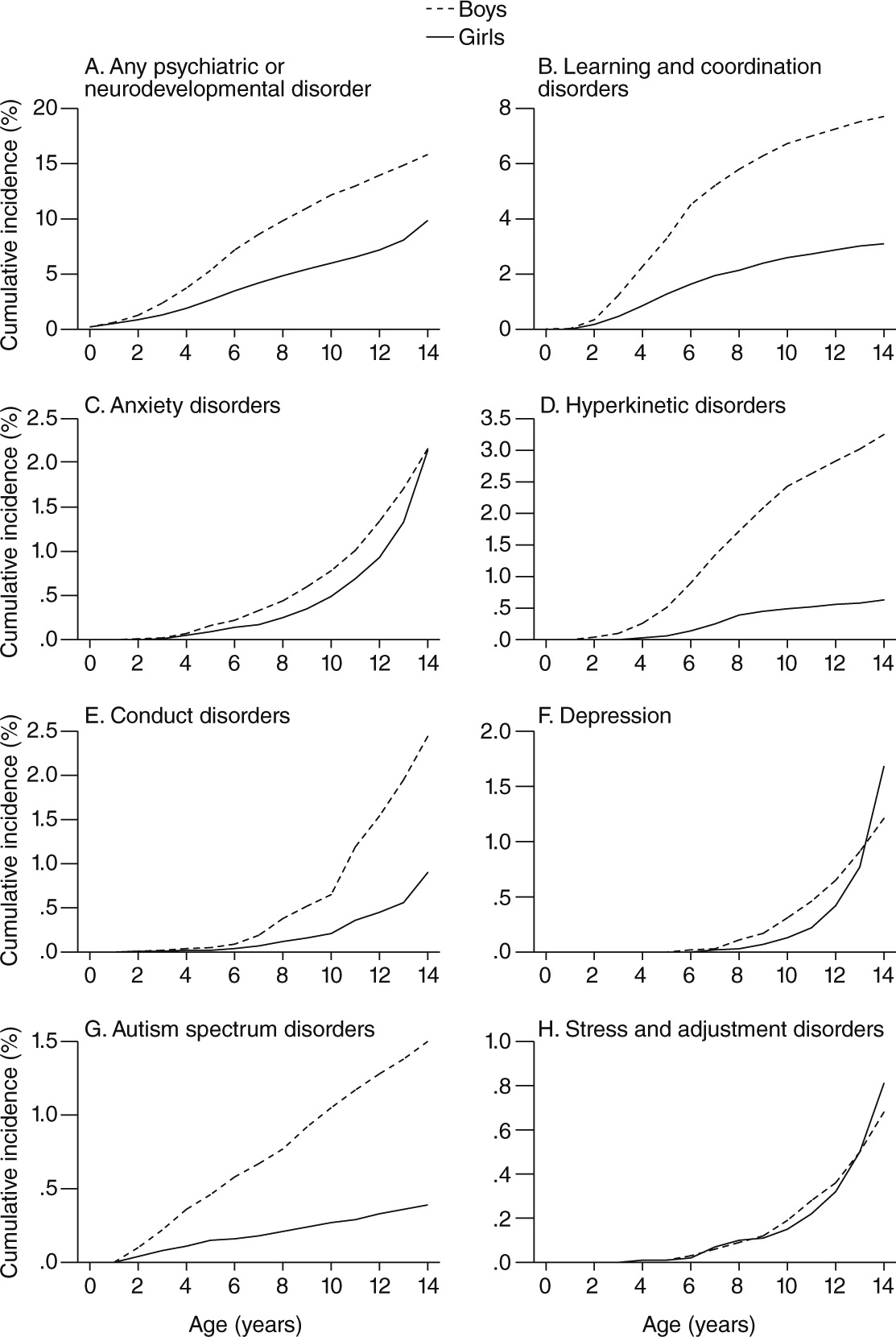

A complete nationwide birth cohort was retrieved from the Finnish register of specialized services to overcome the methodological problems with previous studies. In this report, first, the cumulative incidences from birth to age 14 of a wide range of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders are described and compared with cross-sectional one-year prevalence at age 14. Second, sex-specific cumulative incidences of diagnoses in specialized services from birth to age 14 are described. Third, the lifetime comorbidity of disorders diagnosed in specialized services is described.

Methods

Registers and participants

The data were derived from two Finnish health care registers. The number of live-born children was derived from the Medical Birth Register, which is maintained by the National Institute for Health and Welfare and contains information for all births in Finland. Information on the annual incidence of visits to inpatient (1996–2010) and outpatient (1998–2010) units due to psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders was derived from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (HDR), also maintained by the institute. The register records information on inpatient care in all hospitals and outpatient care in public hospitals, including the child’s personal identification number (PIN), sex, day of admission and discharge, the medical specialty service, and a main diagnosis and secondary diagnosis according to the ICD-10. The diagnoses could be based on any of the main or secondary diagnoses.

All singletons born alive in Finland in 1996 (N=58,538) were included. We chose 1996 because ICD-10 was introduced that year. The outpatient register was established in 1998, but generally, few psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorders are treated before the age of two (in 1996–1997). Therefore, this discrepancy was not expected to considerably affect the results.

This article describes some of the outcomes in the ongoing FinESSI project (

9), but we do not report on assessment of effects of medication use, which is reserved for the FinESSI study. The register administrators and the data protection authority at the National Institute for Health and Welfare approved the use of register data in the FinESSI study (

9). The children were not contacted, and informed consent was therefore not required, according to Finnish law. All frequency tabulations were done internally with encrypted PINs at the National Institute for Health and Welfare, and no person-specific data were extracted from the registers.

Diagnostic groups

The following diagnostic groups were included in the study: any psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorder (ICD-10 codes F00–F99); substance use disorders (F10–F19); nonaffective psychotic disorders (F20–F29, abbreviated to “psychotic disorders”); bipolar disorder (F30–F31); unipolar depression and undefined mood disorders (F32–F39, abbreviated to “depression”); anxiety disorders (F40–F42, F93); stress and adjustment disorders (F43); eating disorders (F50); mental retardation (F70–F79); learning disabilities or motor coordination disorder, including developmental disorders of speech, language, scholastic skills, or motor coordination (F80–F83, abbreviated to “learning and coordination disorders”); pervasive developmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorders (F84); hyperkinetic disorders (F90); conduct disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder (F91, F92); and tic disorders (F95). Lifetime comorbidity, defined as the presence of at least two different diagnostic classes at any time during the follow-up period, was studied between birth and age 14.

Statistical analysis

The follow-up started at birth and ended December 31, 2010, when the participants were 14.0–14.9 years old (born between January 1, 1996, and December 31, 1996). The age of the cohort members was defined as the age on December 31 of the studied year in completed years: the age of 14.0–14.9 years is described as 14 years. One-year prevalence in 2010 was defined as the number of children with visits during 2010, and cumulative incidence was defined as the number of children with an incident diagnosis between birth and 2010. The cumulative incidence of the diagnostic groups was extracted per year of incidence diagnosis and sex from the HDR.

Discussion

The diagnostic groups clustered into three groups with regard to the sex distribution, to the age period when the disorders were first diagnosed, and to lifetime comorbidity in specialized care. First, learning and coordination disorders, autism spectrum disorders, and hyperkinetic disorder were more prevalent among boys and were often diagnosed before school age, and the diagnostic groups overlapped to a certain degree. According to a review of sex differences (

10), these disorders occur mostly among males and typically involve neurodevelopmental impairment. In fact, they are often termed neurodevelopmental disorders (

11). However, the cumulative incidence for these neurodevelopmental disorders continued to increase until the end of follow-up; that is, for many children these disorders were diagnosed in late childhood, although the symptoms per definition must be present before school age. For example, the cumulative incidence of specialized service use for autism spectrum disorders was .5% by age eight and 1.0% by age 14. According to a systematic review from 2012 (

12), the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in recent European studies has ranged between .3% and 1.2%, with a median of .6%. This indicates that a large proportion of Finnish children with autism spectrum disorders sometimes receives a diagnosis in specialized services, but the diagnosis often is established at school age.

Second, conduct disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder, had a male predominance, in line with other studies (

10), but were seldom diagnosed before school age and overlapped to a maximum of 11% with the other diagnostic groups. It is notable that the proportion of children with conduct disorder and a comorbid disorder was low compared with the level of comorbidity in population-based surveys (

13,

14). Although we cannot rule out that hyperkinetic and internalizing disorders are undiagnosed among children with conduct disorder, it is more likely that the low level of comorbidity among children with conduct disorders relates to the diagnostic classification in

ICD-10. There is a specific code for “hyperkinetic disorder associated with conduct disorder” (F90.1) under the chapter of hyperkinetic disorders (F90) in the

ICD-10, and there is a separate group for “mixed disorders of conduct and emotions” (F92). Accordingly, hyperkinetic disorders associated with conduct disorder were classified as hyperkinetic disorders, and mixed disorders of conduct and emotions were classified as conduct disorders.

Third, prevalence of anxiety disorders, depression, and stress and adjustment disorders was relatively equal between boys and girls, and these disorders were often diagnosed in late childhood or early adolescence, with lifetime comorbidity of these disorders present in many cases. In line with a previous review (

10), anxiety and depressive disorders had a similar sex distribution in prepubertal years but were more prevalent among females after puberty. Depression and anxiety are often termed emotional disorders, whereas stress and adjustment disorders can involve both emotional and disruptive symptoms. The diagnostic pattern of stress and adjustment disorders resembled the pattern seen mostly with emotional disorders. Some children first received diagnoses of stress and adjustment or anxiety disorders and later received a diagnosis of depression, because there was a high proportion of comorbidity between these disorders and the age at which stress, adjustment, and anxiety disorders were diagnosed was earlier than the age for a diagnosis of depression.

Several methodological issues should be considered when comparing the cumulative incidence results with the results from other service use studies. For example, survey-based studies potentially are prone to recall bias, whereas register-based studies are not; register-based studies include only specified services, whereas surveys can collect information for different forms of service; and some registers allow for long-term follow-up at the individual level, whereas other registers do not. A novel finding was that 8% of boys and 3% of girls had used specialized services for learning and coordination disorders between birth and age 14, when the data were treated as longitudinal data, but the corresponding proportion was only .9% for boys and .4% for girls when the register-based data were treated as cross-sectional data at age 14. This difference indicates that most Finnish children with learning and coordination disorders visited specialized care only for a short time and that long-term follow-up designs are necessary for identifying these disorders in register-based research. The longitudinal cumulative incidence estimates of learning and coordination disorders, rather than the cross-sectional one-year prevalence, resemble results from surveys. For example, in a cross-sectional U.S. survey from 1997 to 2008 (

15), teachers or health professionals had identified 9% and 5% of three- to 17-year-old boys and girls, respectively, with learning disabilities. Future studies with both survey-based and register-based information are needed to investigate to what extent these kinds of information differ.

The cumulative incidence of specialized service use for conduct disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder, was 1.7% by age 14. The comparison with community-based samples is challenging because of methodological issues, but this figure can be considered low. For example, the three-month prevalence of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder among Finnish eight- to nine-year-old children was 5% in a study based on parental interviews (

16), and similar figures have been found in the United Kingdom (

17) and the United States (

18). Similarly, anxiety disorders in specialized care had a cumulative incidence of 2.2% by age 14, whereas the three-month prevalence of anxiety was 5% at age eight in a sample of Finnish children, including children who received treatment and children who did not (

16). In line with previous studies (

1,

2), this difference indicates that in Finland some psychiatric problems, such as conduct and anxiety disorders, are underrecognized in primary care or are not referred to specialized services.

It is well known that neurodevelopmental disorders occur more often among boys than girls, because of different risk and protective factors between the sexes (

10). It is also acknowledged that the sex ratio for service use for disorders might be even higher than the sex ratio for the disorders per se (

10). As when comparing cumulative incidence with other studies, comparing sex ratios with other studies is challenging because of methodological differences. For example, the boy-girl ratio for autism spectrum disorders was 3.8:1.0 in our study, compared with 2.5:1.0 in a recent epidemiological study from South Korea (

19) and 3.9:1.0 in another epidemiological study from the United Kingdom (

20). The ratio in this study indicates that there was no major gender bias in referral of children with autism spectrum disorders to specialized services in Finland, but studies with more detailed data on nontreated cases are needed to confirm these findings and give insight into possible gender biases of the full spectrum of disorders.

The strengths of this study include total nationwide longitudinal data from birth, both inpatient and outpatient units from all specialties, and a uniform diagnostic system (

ICD-10). There are also several limitations to consider. The results represent all children with specialized service use for psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders in Finland but lack information about children who are not recognized by primary care and are not referred to specialized services. Having such information would allow more definitive conclusions to be drawn in regard to unmet need of services and under- and overdiagnosis. Furthermore, the data required complete information concerning specialized service use, because data on primary care visits are not yet available for research purposes in Finland. In addition, the diagnostic validity of childhood autism has been assessed and has been found to be high (

21), but it is not known how well other disorders correspond to research diagnostic criteria. Moreover, the total sample was based on all singleton live births, but emigration, immigration, and deaths were not taken into account in the analyses. However, mortality is very low, emigration ranges between .1 and .4% per year, and immigration ranges between .3 and .8% per year among Finnish people between birth and age 14 (

22). It is therefore unlikely that these factors would substantially affect the results.