The 2008 Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA), implemented in 2010, requires equity between coverage for mental and substance use disorders and for other medical conditions. Because of the law's recent implementation, there is no empirical evidence on MHPAEA's effects, and rigorous study of the effect of a national policy poses methodological challenges. Therefore, it may be informative to study the effects of parity implemented in other contexts, such as the comprehensive parity directive in the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program.

Previous studies have indicated that when combined with management of care, parity in the FEHB Program did not increase total spending on behavioral health care or the probability of service use, but beneficiaries' out-of-pocket costs were significantly lower after parity compared with enrollees in unaffected health plans (

1–

3). These results were attributed in part to changes in health plans' management of care for behavioral health conditions after implementation of the FEHB Program parity directive (

4,

5). This evidence is credited with influencing lawmakers to pass the MHPAEA (

6), which in turn set the stage for Congress to mandate behavioral health benefits in health insurance reform in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 (

7).

At the time of the original evaluation of parity in the FEHB Program, the investigators did not explore whether the quantity of specific services, such as hospital care, psychotherapy, or medications, changed or whether the prices of these services changed. The finding of no change in total spending on behavioral health care in response to parity might mask changes in the intensity of use of specific services or in the prices paid for them. The primary focus of the impact of managed behavioral health care has been on the quantity of services delivered. Beneficiaries and clinicians have expressed concern that managed care organizations constrain utilization of care through restrictions and denials. Clinicians have also expressed frustration with reimbursement rates paid by managed care organizations. Instead of constraining utilization, health plans or managed behavioral health carve-out organizations could control total spending by negotiating lower prices for specific services or reducing the price of services through use of less costly providers, such as by hiring social workers rather than psychologists or psychiatrists to provide psychotherapy. One hypothesis is that parity led to an increase in service use over time (as expected by some advocates and opponents of parity alike), but health plans managed to control total spending by reducing the prices of the services to balance the increase in use. A recent study demonstrated that U.S. health care costs are driven by high and rising prices for services as much or more than by increases in the volume of services delivered (

8).

This column addresses the question: what happened to the quantity of use of various behavioral health services after implementation of parity in the FEHB Program, and what does that say about the price of such care?

How did we assess the quantity and price of services?

To assess how parity in the FEHB Program affected the quantity and price of behavioral health services, we used a quasi-experimental design to account for secular trends in service use not associated with implementation of the parity policy. We compared utilization in seven large FEHB preferred-provider organization (PPO) plans from 1999 through 2002 (comparing two years before and two years after parity implementation) with utilization in a set of PPO plans from Thomson Reuters MarketScan database that did not experience changes in behavioral health coverage during this period. Most of the comparison plans were operated by large, self-insured employers. We studied service use by persons who were continuously enrolled in a plan before and after implementation of the parity policy. Our study population included persons with any use of behavioral health services in either 1999 or 2000, the two years before parity implementation. [Details about how service use was identified are available in an appendix to this column at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Key outcomes examined were the quantity of services used within specific categories, including number of inpatient days, total number of mental health outpatient visits (combining medication management visits, therapy visits, and other types of outpatient visits), number of medication management visits, number of therapy visits, and number of prescriptions for medications to treat behavioral health conditions. These services together accounted for 98.7% of all behavioral health expenditures in the preparity period. Our primary interest was in determining whether the distribution of the quantity of services used within each category changed after parity (2001–2002) compared with the period before parity implementation (1999–2000) in FEHB plans relative to the comparison plans.

We did not directly assess the change in prices of these services, because this can be complicated in administrative data, requiring many, often untestable, assumptions. Rather, we inferred changes in average prices by directly measuring changes in the quantity of services in the five specific service types described above. If after we controlled for secular trends, the quantity of psychotherapy visits, for example, rose over after parity implementation, then we would infer that because total spending remained unchanged, a reduction in the price of therapy visits had occurred. Again, it is important to note that a decrease in price might be attributable to either a reduction in the reimbursement rate for the service or the substitution of a lower-cost service provider. Conversely, if there was a clear pattern of declining service use in various categories, then the lack of change in total spending would be attributable to rising, rather than declining, prices for care in the FEHB plans compared with the secular trend of prices for the comparison plans.

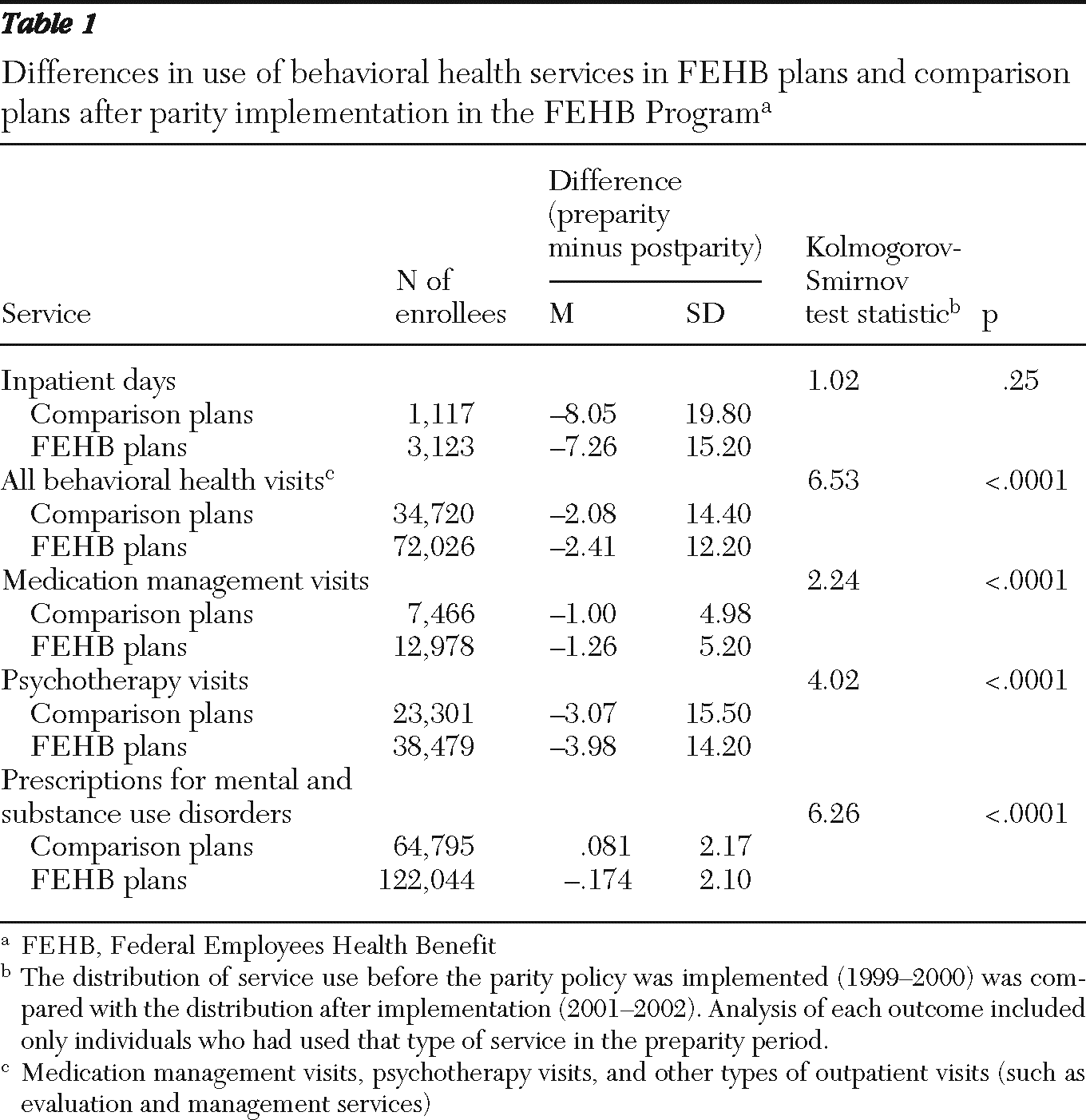

We identified 140,369 FEHB plan enrollees and 70,456 enrollees in comparison plans who used any behavioral health services during the preparity period. The numbers of enrollees who used any of the five specific categories of behavioral health services are shown in

Table 1. Enrollees may have used several of the categories of services.

We performed Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests to compare the change in the range of use of a given service from pre- to postparity among FEHB and comparison group enrollees who used that service in the preparity period. One strategy for health plans in the FEHB Program to control costs after parity implementation was to contract with a managed behavioral health care carve-out firm (

4). As a sensitivity analysis, we conducted stratified analyses to determine whether a plan's adoption of a carve-out contract before or after parity might have affected the results. Because we conducted multiple tests (for each category of service and for different subsets of plans defined by the presence of a carve-out), we considered differences to be statistically significant if the p value was less than .0001. Tests were performed with the procedure NPAR1WAY in SAS, version 9.2.

What did the analysis of changes in use reveal about prices?

As shown in

Table 1, in both the FEHB plans and the comparison plans, a substantial decline occurred in all categories of service use after parity was implemented (2001–2002) compared with the preparity period (1999–2000). For example, the mean number of inpatient days declined by 7.26 inpatient days in the FEHB plans and by 8.05 inpatient days in the comparison plans. Likewise, outpatient behavioral health visits declined by 2.41 visits in the FEHB plans and by 2.08 visits in the comparison plans. With the exception of inpatient days, the decreases in utilization were significantly greater for enrollees in the FEHB plans than for those in the comparison plans. The effect of parity on the quantity of services used was also remarkably stable whether or not a health plan had a carve-out contract before parity or shifted to a carve-out contract after parity (see online appendix at

ps.psychiatryonline.org).

Previous studies have shown that the increase in total spending after parity was no greater in the FEHB plans than in comparison plans (

1–

3). Therefore, the results of the analysis presented here, which indicate that the quantity of services used actually declined—and declined significantly more in the FEHB plans—suggest an increase in the prices of these categories of services over the period examined. The results also suggest that the increases were greater in the FEHB plans than in the comparison plans.

What are the implications of a rise in prices?

This analysis suggests that the absence of an increase in total spending after parity implementation in the FEHB Program was not attributable to a decline in prices for services. That is, the main impact of parity (and of changes in care management that may have accompanied parity) was a decline in the quantity of services delivered and not in the prices paid. Despite an increase in prices, out-of-pocket expenses declined as a result of parity (

1–

3).

Results of the main analyses (as well as the sensitivity analyses for use of a carve-out for behavioral health management) suggest that care management played a role in reducing the utilization of services. Previous studies of care management in the FEHB Program suggested that plans used several techniques to manage care, including mechanisms as simple as requiring written treatment plans (

4,

5). Other managed care techniques that health plans may have used to control increases in utilization (including in the context of benefit expansion) include prior authorization requirements, utilization review, and changes in the design of the provider network. In this study, we were not able to directly observe supply-side changes in the management of care in response to parity implementation; we can only infer the effects. More research is required to elucidate the mechanisms at work between utilization management and benefit design.

Providers and beneficiaries can expect that parity under the MHPAEA may also be accompanied by changes in care management. It is important to note that one critical difference between the parity directive in the FEHB Program and the MHPAEA is related to care management. The Office of Personnel Management, which administers the FEHB Program, encouraged plans to use managed care techniques to control any increases in behavioral health expenditures that could result from the parity benefit expansion. In contrast, an important feature of the MHPAEA Interim Final Regulations, effective January 2011, is the application of parity to both quantitative treatment limits (for example, visit limits, day limits, and higher copayments) and “nonquantitative” limitations (for example, utilization management, formulary design, and criteria for participation in the network of behavioral health service providers) compared with services for other medical conditions. Thus, under the MHPAEA, health plans are required to apply plan management techniques no more stringently for behavioral health care than for other medical care.

It remains to be seen how these regulations will be enforced in practice. Findings from this study suggest that at least in the case of the FEHB Program, the quantity of specific services used—rather than the prices of these services—declined in response to parity. Full implementation of the MHPAEA and of health care reform under the ACA will provide additional opportunities to assess how benefit regulation affects the price and quantity of services to treat behavioral health conditions.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grants R01-MH080797 and K01-MH071714 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grant R01-DA026414 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors thank Hocine Azeni, M.A., for expert statistical programming.

The authors report no competing interests.