Early intervention programs for schizophrenia and bipolar disorders have gained traction in recent years. The aim of these programs is to improve clinical and social outcomes of these diseases by intervening while the individual is at risk of or in the initial stages of the illness (

1). Young people at risk of psychosis may be labeled as having a mental illness because of early signs of the disorder or as an unintended consequence of early intervention (

2–

4). Qualitative studies found that stigma is a common concern of individuals experiencing early psychosis (

5). However, quantitative data on labeling and stigma among young people at risk of psychosis appear to be lacking (

6).

Mental illness stigma mainly comes in two forms. Public stigma refers to endorsement of negative stereotypes of individuals with mental illness by members of the general public (

7,

8). Self-stigma occurs when persons with mental illness agree with and internalize negative stereotypes (

9) and is typically associated with shame about having a mental illness (

10). Two models help explain how public stigma and self-stigma may affect young people at risk. First, according to Link and others’ (

11) modified labeling theory, individuals are aware of societal negative attitudes toward persons with mental illness (perceived public stigma). Once a person has been labeled as having a mental illness, these public attitudes become self-relevant, potentially threatening and negatively affecting feelings of well-being (

12,

13). Second, stress-coping models conceptualize stigma as a stressor for people with mental illness (

14–

17). Stigma stress occurs when stigmatized individuals perceive that the harm due to stigma (primary appraisal) exceeds their resources to cope with this threat (secondary appraisal), and stigma stress can undermine well-being (

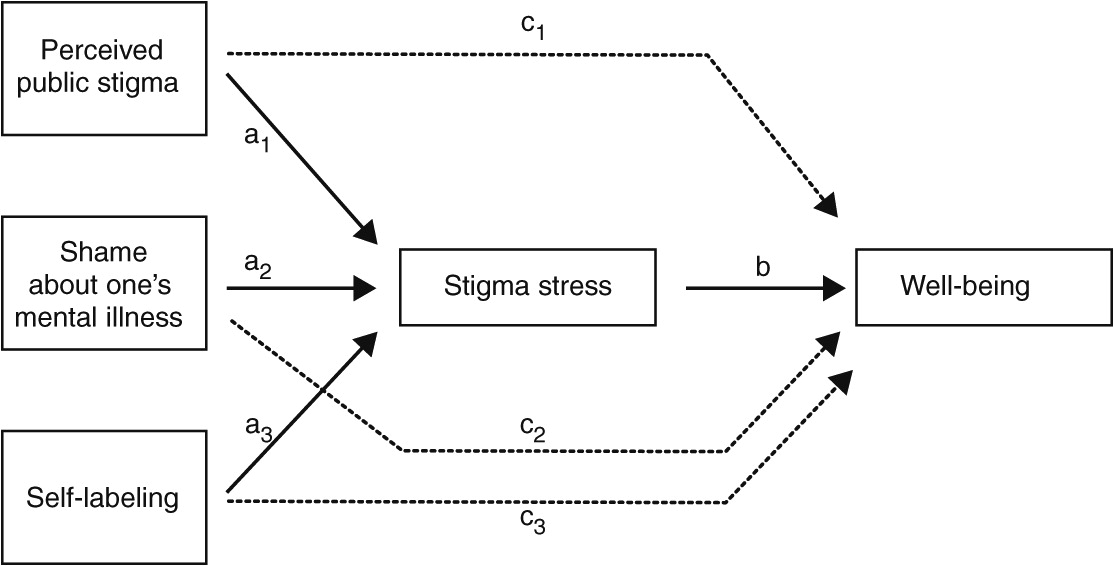

Figure 1).

The overall aims of this study were twofold—first, to collect data on the relationship between self-labeling, stigma, and well-being among people at risk, and second, to examine how the underlying mechanisms of the stress-coping model may explain how stigma affects this group. Both questions have policy and research implications. For instance, if stigma is unrelated to well-being, it would need less future attention. If the two are related, a better understanding of the mechanisms involved can inform interventions to reduce public stigma and self-stigma associated with at-risk status.

We tested the following hypotheses among young people at risk of psychosis or bipolar disorder who did not yet fulfill diagnostic criteria of either disorder (

Figure 1). First, we expected that higher levels of perceived public stigma, shame about one’s mental illness (a proxy for self-stigma), and self-labeling as having a mental illness would predict more stigma stress. Second, we anticipated that increased stigma stress would predict reduced well-being after the analyses controlled for symptoms, comorbid psychiatric illnesses, and sociodemographic variables. Third, we expected that stigma stress would mediate the effect of public stigma, shame, and self-labeling on well-being.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that stigma-related stress is associated with impaired well-being among young people at risk of psychosis, independent of symptom levels, comorbid psychiatric disorders, age, and gender. Regarding the overarching aims of this study, our results have two potential implications. First, labeling and stigma should be taken into account by early intervention and prevention programs. Second, a stress-coping model may be useful to understand some of the mechanisms involved in the damaging effects of stigma. That said, our results should be replicated, and longitudinal studies are needed to establish causality between, for example, stigma stress appraisals and reduced well-being among people at risk.

The results support our first hypothesis that public stigma, shame (a proxy of self-stigma), and self-labeling as “mentally ill” independently contribute to the appraisal of stigma as a stressor that exceeds one’s coping resources. Therefore, interventions that aim to alleviate stigma’s impact in this population should address both public stigma and self-stigma. It is consistent with Lazarus and Folkman's (

14) stress-coping model that perceived public stigma as an external threat was associated more strongly with perceiving stigma as harmful than with one’s coping resources. The negative effects of shame are probably greater than suggested by our findings because we were not able to assess other negative consequences—besides stigma stress—that are typically associated with shame, such as secrecy, social withdrawal, or other dysfunctional coping styles (

10).

Self-labeling contributed to stigma stress, which highlights how labels for mental illness function as a two-edged sword. On the one hand, they might have positive effects, such as facilitating treatment (18); on the other hand and in accordance with Link and colleagues' (

11) modified labeling theory outlined above, they increase the vulnerability of individuals to stigma and discrimination (

38). Furthermore, by labeling oneself as “mentally ill,” one comes close to identifying with the group of people with mental illness. Consistent with the findings of this study, research has shown that group identification has mixed effects on stigmatized individuals, depending on the social environment and on how positively persons value their own group (

15,

39).

The link between perceived public stigma, shame, and self-labeling and reduced well-being was mediated in part by stigma stress, supporting our third hypothesis. Consistent with stress-coping models of stigma (

15,

26), this finding highlights the extent to which the cognitive appraisal of stigma as a stressor is a key determinant of reactions to stigma. Stigmatized individuals are not passive recipients of stigma, and their response can augment or reduce stigma’s negative impact. This observation, of course, is not meant to blame people with mental illness for experiencing stigma, which remains a societal injustice. But as long as stigma persists, positive coping processes could help stigmatized individuals and be encouraged in different settings, for example, by improving disclosure strategies or reducing shame associated with mental illness (

40–

42).

This study had several limitations. The role of family members, caregivers, peers, and health care professionals was not examined. Future studies should compare the impact of stigma variables among persons at risk of psychosis, persons with established early psychosis, and persons with a long history of psychotic disorders; that said, stigma stress levels in this study were slightly higher than among individuals from the same region with a long history of mental illness and recent involuntary psychiatric hospitalization (

27). Because we recruited a convenience sample in a Swiss metropolitan area, our findings cannot be generalized to other settings. Psychiatric comorbidity was common, as is typical among samples of individuals with early psychosis (

43); although we assessed self-labeling, the participant’s history of having been labeled—for example, due to at-risk status, psychiatric comorbidity, or previous contact with health services—was not assessed. However, controlling for psychiatric comorbidity did not affect our findings. Finally, except for symptom ratings, the data were based on self-report.

Conclusions

Early recognition and intervention programs for people at risk of psychosis will become more common, and recent findings highlight the potential benefits of such treatments (

1,

44). However, our results suggest that treatment alone may not be sufficient to overcome the deleterious effects of stigma. Interventions to help young people at risk of psychosis respond to stigma, shame, and social exclusion are needed as well. This effort is especially relevant because social networks appear to be impaired even before the first onset of psychosis (

45).

Researchers, policy makers, clinicians, family members, and (potential) service users should critically discuss the costs of early intervention in terms of labeling and stigma: should they avoid using the “at risk” label, not only in psychiatric classifications (

46) but also in clinical settings? Are labeling and stigma an acceptable price to pay for early intervention? The answer does not become easier when one considers that according to current estimates, a majority of individuals deemed to be at risk will not develop a psychosis (

1). We need thorough longitudinal studies about the effects of labels and stigma in different settings on different groups of people at risk, including those who do not eventually develop psychosis. It seems likely that in order to minimize stigma’s negative impact, we will need programs that address both public stigma—for example, among key groups such as teachers and adolescents—and self-stigma, as well as early intervention services that minimize shame and stigma stress (

47). Only a comprehensive approach, taking into account emerging symptoms as well as labeling, shame, and stigma, is likely to address the needs of young people at risk and to increase their chances to achieve full recovery and social inclusion.