Seclusion and restraint are physical interventions used by staff to control aggressive or self-destructive behavior of adults and children in mental health and other settings, including psychiatric hospitals, emergency rooms, residential programs, and schools (

1). Controversial for centuries, these practices are now closely regulated or restricted by a variety of accreditation standards, agency and facility policies, and recommendations and guidelines from professional and trade organizations. These generally consider seclusion and restraint as interventions of last resort, to be employed only when the safety of staff or patients is immediately jeopardized and less coercive alternatives have been considered (

2).

Increasing numbers of consumers, advocates, public agencies, and providers view seclusion and restraint more restrictively, believing current standards allow too much latitude, when otherwise these practices could be significantly reduced or even eliminated (

3). From this perspective, seclusion and restraint are not interventions but adverse events resulting from treatment failure (

4). Studies showing wide variation in rates independent of patient characteristics and reports of successful reduction initiatives support the potential benefits of quality improvement approaches on a broader scale (

5–

8). Epidemiological studies indicating high rates of trauma history among persons with serious mental illness (

9) and consumer accounts of the traumatizing effect of these practices (

10,

11) lend weight to ethics-based objections. With a broad range of stakeholders increasingly engaged in efforts to transform the mental health system to support recovery, consumer autonomy, and social integration, the persistence of these coercive practices remains a troubling anomaly (

12–

14).

Coercive measures in mental health treatment are also contradictory to the goals of large-scale efforts to improve the nation’s health care system. Systematic reviews have marshaled evidence indicating that seclusion and restraint increase risks of physical and psychological harm (

2,

15) and add to the organizational costs of mental health care (

16) while providing no therapeutic benefit (

17). Thus these coercive measures conflict with high-profile initiatives, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “triple aims” to improve population health and the patient experience of care while reducing per capita cost (

18) and the national movement to improve patient safety in health care (

19).

Despite expenditure of considerable resources toward the goal of reducing seclusion and restraint in the form of policy initiatives, regulations, reports, research evidence, media coverage, government and foundation grants, practice guidelines, and legal cases (

2,

4,

8,

20), these practices continue to be common in psychiatric facilities. A report from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Research Institute (NRI), based on aggregate data from approximately 200 facilities indicated that in a given month from 2002 to 2009 approximately 3.5% to 4.0% of patients were restrained and 2.2% to 2.8% were secluded (

21). To place this in a quality context, these seclusion rates are in the midrange of patient falls in acute care hospitals, the top adverse event in this setting (

22).

This article presents results of a study that found patterns of increasing and decreasing fidelity in relation to changes in seclusion and restraint rates over a four-year period in 43 inpatient psychiatric facilities and residential treatment programs that were implementing the clinical model Six Core Strategies to Prevent Conflict and Violence: Reducing the Use of Seclusion and Restraint (6CS). These facilities were in eight states that received grants in 2004 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to implement best practices for reducing the use of seclusion and restraint. 6CS was the model chosen by all eight grantee states.

Developed by NASMHPD National Technical Assistance Center (NTAC), 6CS is a synthesis of strategies shown to be effective in reducing the use of seclusion and restraint, organized as a prevention-based training curriculum (

3,

23–

25). The six strategies are topic areas: leadership, debriefing, use of data, workforce development, tools for reduction, and inclusion of consumers, family members, and advocates. An NTAC program, the National Executive Training Institute (NETI), has provided training in 6CS to state agency and provider leadership in nearly every state.

Proctor and colleagues (

26) have identified eight essential implementation outcomes for new mental health programs: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, costs, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability. Our study focused primarily on fidelity, defined as “the extent to which delivery of an intervention adheres to the protocol or program model originally developed” (

27) and sustainability, which Proctor and colleagues defined as “the extent to which a newly implemented treatment is maintained or institutionalized within a service setting’s ongoing, stable operations.”

Methods

Data

We collected individual-level information on facility and patient characteristics and, linked by common identifiers, patient-level seclusion and restraint events in a format consistent with the measure specifications of the Behavioral Health Performance Measurement System (BHPMS). The BHPMS is a proprietary system developed by NRI, used by most state and many private psychiatric hospitals for purposes of Joint Commission accreditation, and licensed for use in this study. BHPMS measures of seclusion and restraint rates are specified as the percentage of clients secluded or restrained at least once during the report period (unduplicated number of inpatients with at least one seclusion or restraint event as the numerator, and total unduplicated number of inpatients as the denominator), and duration of seclusion or restraint events (total hours of seclusion and restraint as the numerator, and total number of inpatient hours as the denominator).

Implementation over time was measured with the Inventory of Seclusion and Restraint Reduction Interventions (ISRRI), a prototype scale to measure fidelity to the practices prescribed in the 6CS. The ISRRI was developed through a consensus process involving the research staff and the developers of the 6CS, who reviewed the NETI training curricula to identify each recommended activity, policy, and practice. A total of 138 items were identified, each coded as a single bivariate response (implemented: yes or no). A simple approximation of reliability testing was carried out before administration, The research team and NTAC consultants separately completed several ISRRIs and then identified and resolved differences. In addition, when NTAC consultants conducted site visits to facilities, they completed a separate ISRRI, which was then compared with the one submitted by the facility.

Researchers have recommended that fidelity measurement be conducted periodically (

27). The ISRRI was completed twice online, once early in the study (2004) to establish a baseline because many facilities had already initiated some features of the 6CS, and a second time near the end of the study period in 2007. The ISRRI, which was completed by facility staff knowledgeable about their reduction program, required respondents to indicate retrospectively whether and when a particular activity had been implemented. In the second administration, they were also required to identify any activities that had been discontinued and when this occurred. The resulting information allowed for the construction of fidelity score trend lines representing patterns of implementation over time.

The SAMHSA program also supported a center to provide technical assistance to grantees. To test the hypothesis that technical assistance would enhance implementation, we obtained information about the number of site visits and units of technical assistance provided to each facility.

Participating facilities received a detailed protocol for data collection and Web-based submission, accompanied by Web-based training. The computer application for online data entry included stringent logic checks with notification to users of errors. Data use agreements with grantee states allowed for the use of limited (that is, deidentified) data sets containing information on treatment episode and seclusion and restraint events in the form used for the BHPMS. As deidentified administrative data, these were exempt from requirements for institutional review board approval.

Statistical methods

Linear modeling and meta-regression approaches controlling for covariates were used to examine changes in seclusion and restraint rates relative to the extent to which the 6CS was implemented. Controlling for covariates was necessary because the effects of 6CS over time could be confounded with changes in the patient population. Covariates were determined by two tests. Correlations between consumer characteristics and the dependent variables (changes in seclusion and restraint rates) were measured, and characteristics that were correlated were tested to determine whether the groups in the preimplementation and stable implementation periods differed with respect to these. Characteristics that differed significantly between the two periods were incorporated into the analysis as covariates.

Because each of the four outcomes measures was related to a different combination of covariates, different general linear models (GLM) were employed for each of the four outcomes. The GLM-predicted values (change in seclusion and restraint rate from preimplementation to stable implementation with controls for the effect of significant covariates) were incorporated into meta-regression models that synthesized seclusion and restraint rates across all facilities and by subgroups of similar facility types.

Dose-effect analysis

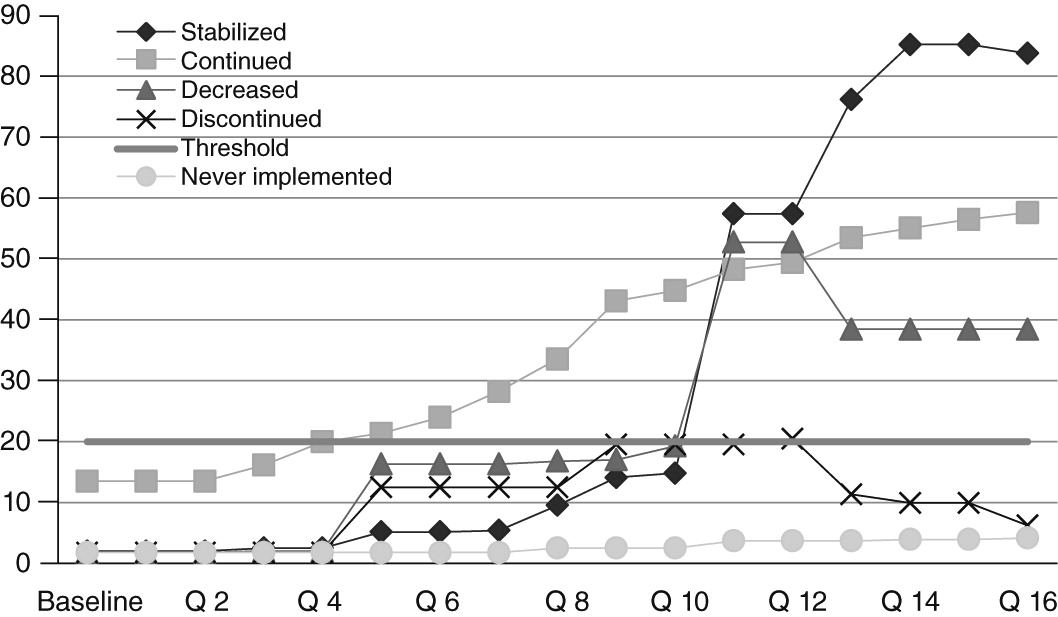

The dose-effect analysis tested the hypothesis that reductions in seclusion and restraint would be greater in facilities where implementation reached a certain threshold and remained consistent over time and that reductions would be smaller in facilities that were continuing to innovate (because of the temporary disruption that innovation creates) and in facilities that never reached, or that fell below, a required threshold. To sort facilities into five theory-based patterns of implementation represented by ISRRI score trend lines, a level of implementation hypothesized to be minimally necessary for the reduction program to have an effect was set as an ISRRI score of 20%. Then facilities were classified according to ISRRI score trend lines into five implementation categories: implementation continuing, passing the threshold then continuing to increase fidelity by adding components throughout the time frame (N=7); implementation decreasing, passing the threshold to reach a plateau and then subsequently declining by more than 10% (N=5); implementation discontinuing, passing the threshold but then subsequently falling below it (N=1); never implemented, never reaching the threshold score (N=2); and implementation stabilized, passing the 20% threshold then reaching a steady state of an ISRRI score that did not increase or decrease by more than 10 points over a four-month period (N=28). Only the 28 facilities in the stabilized category were included in the outcomes meta-analysis. These threshold levels of 20% minimum and 10% variation, though somewhat arbitrary, were chosen to maximally differentiate groups of facilities on the basis of the range and pattern of ISRRI scores. Examples of these implementation categories are shown in

Figure 1.

Results

The unit of analysis was the individual psychiatric facility. Most of the 43 facilities (N=34, 79%) were freestanding psychiatric hospitals. Only three (7%) were residential programs, and six (14%) were psychiatric units in public health or private hospitals. Facilities varied considerably in size, with nine (21%) having 50 or fewer beds and ten (23%) more than 200 beds. Most (N=31, 72%) served only adults, and all but two (5%) were state operated. Most (N=34, 79%) contained several units with diverse functions. [Tables summarizing facility information are available in an online

data supplement to this article.]

Most characteristics identified as being related to differences in seclusion and restraint rates, and therefore tested as covariates, were represented in most of the facilities’ populations, although with considerable variation in proportions.

Most facilities (N=38, 88%) received technical assistance from NTAC during the course of the project. Over half (N=23, 53%) received site visits from NTAC during the course of the project.

Implementation

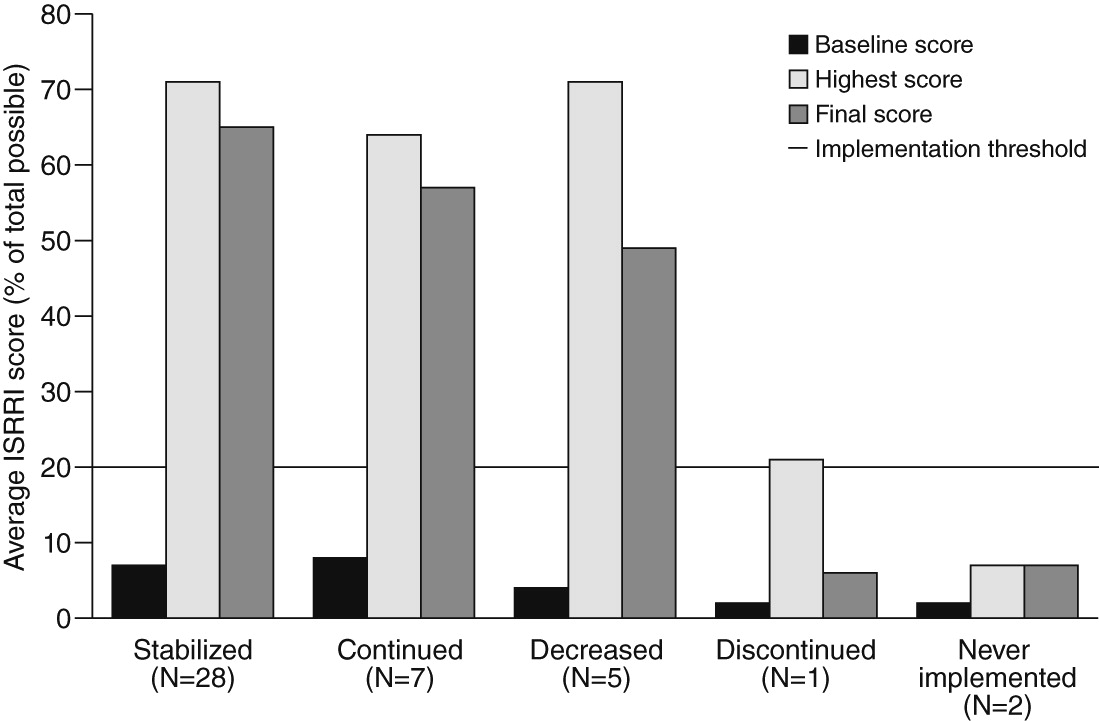

The number of facilities in each implementation category is shown in

Figure 2, along with each category’s average score at baseline (preimplementation), highest score, and final ISRRI score. It is noteworthy that implementation peaked and then declined for all four categories that reached the implementing threshold.

Dose-effect analysis

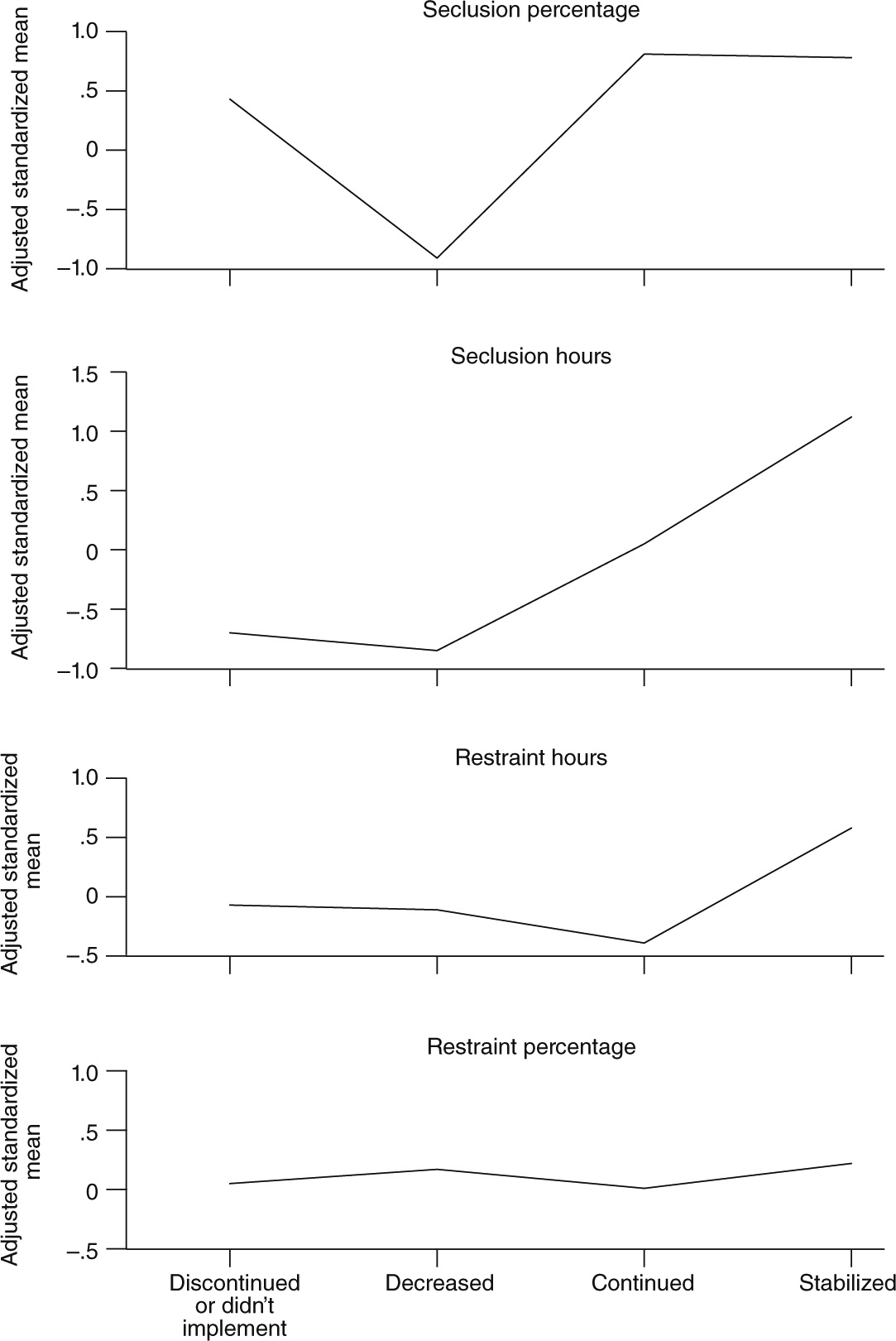

The dose-effect analysis tested the hypothesis that facilities in the stabilized implementation category (N=28) would have sharper declines in seclusion and restraint rates than facilities in the other implementation categories. The results shown in

Figure 3 indicate that the hypothesis was supported with respect to two of the four outcome measures—those related to average duration of seclusion and restraint events—but not to the proportion of the population secluded or restrained. Facilities in the stable implementation group had the greatest mean change in seclusion hours per 1,000 treatment hours (r=.88, p=.02) and in restraint hours per 1,000 treatment hours (r=.46, p=.05). The greatest reduction in percentage secluded, however, was achieved by facilities in the implementation continuing group. Group differences in the change in the percentage of patients restrained were nonsignificant. It is also noteworthy that the order of the implementation categories in relative degree of change varied with respect to the four outcomes.

Technical assistance

Tests of the hypothesis that technical assistance would enhance implementation produced inconclusive results.

Seclusion and restraint reduction with stable implementation

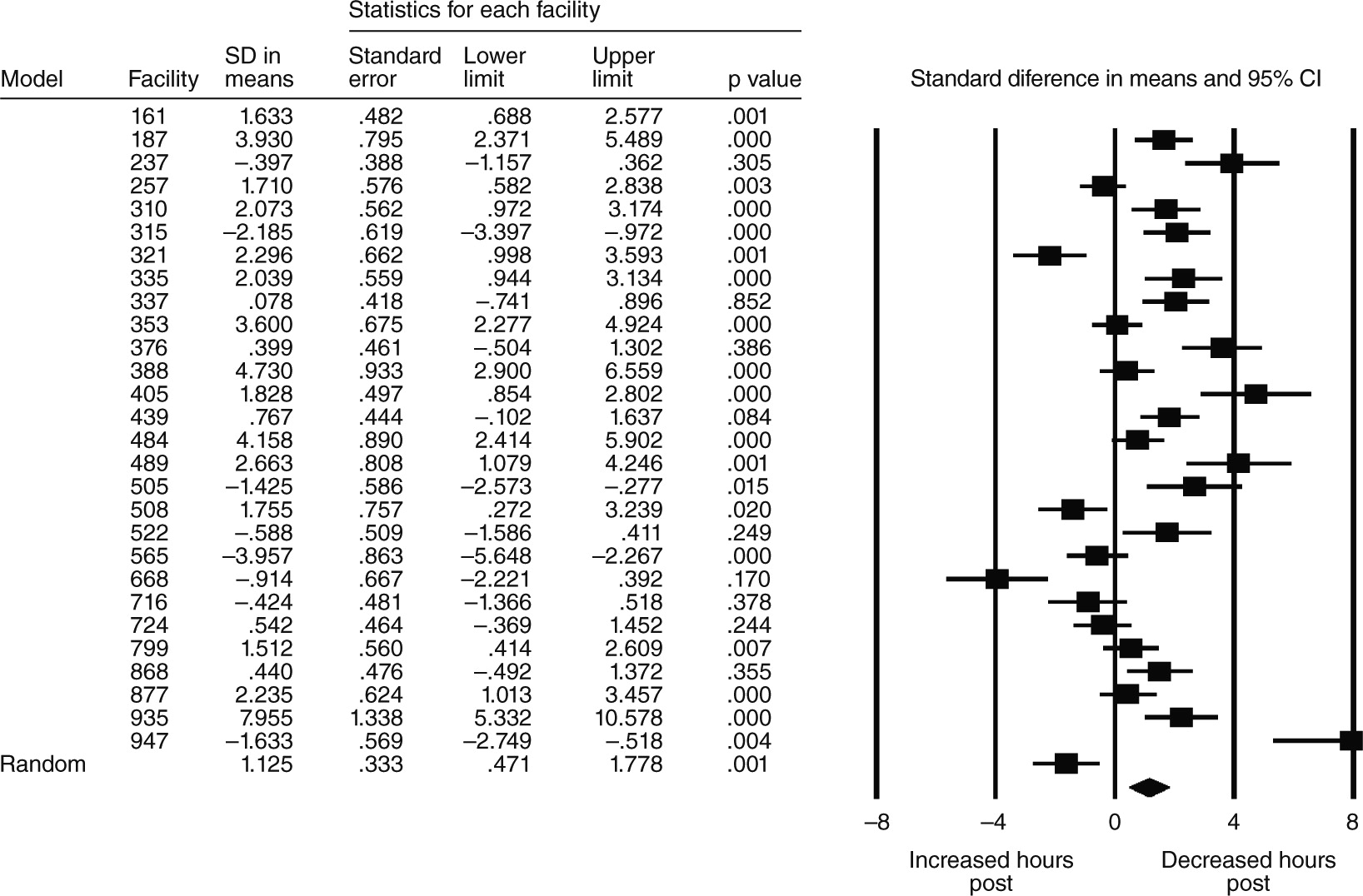

Table 1 presents results of the random-effects meta-analysis (change in weighted means of percentage and hours of seclusion and restraint) for the 28 facilities that reached stable implementation. Nine achieved reductions in the percentage of the overall population secluded, with an average reduction of 17% (p=.002). Fifteen reduced the amount of seclusion hours per 1,000 treatment hours, with an average reduction of 19% (p=.001). Nine facilities achieved reductions in the percentage of patients who were restrained, with an average reduction of 30% (p=.027). Twelve facilities achieved reductions in the hours of restraint, with an average of 55%, although the change was not significant.

Figure 4 is the forest plot of meta-analysis results for one of the four outcomes—number of seclusion hours.

Discussion

Various studies that track fidelity over time have been conducted (

28,

29) or proposed (

30). To our knowledge, this is the first study to use the approach of dynamic fidelity measurement to track advances and declines in the implementation of program components over time and compare these with outcomes in dose-effect analysis.

Researchers have recently recognized that even successfully implemented evidence-based and innovative programs may fail to be sustained for a variety of reasons, an outcome described by Massatti and colleagues (

31,

32) as “de-adoption.” Results of the dynamic fidelity measurement approach of this study, which showed drop-offs in many facilities, suggest that longer-term implementation studies may find that “de-adoption” is an important phenomenon.

The forest plot in

Figure 4 shows one of the outcomes—change in hours secluded—that was positive for the 28 facilities overall. However, for eight facilities, no change was noted, and four actually had increases in hours of seclusion, an inconsistency that would not have been evident with a methodology that simply pooled effects across facilities.

The hypothesis that facilities in the stabilized implementation category would have achieve greatest improvements in seclusion and restraint rates was supported for duration of seclusion and restraint events but not for percentage of patients secluded or restrained, suggesting the possibility of underlying differences in how reduction strategies influence duration versus incidence of seclusion and restraint events. In addition, the order of the other categories in their relative effectiveness varied depending on the particular outcome variable, suggesting subtleties in the relationship between fidelity and outcomes that we are unable to explain. These variations in the results of the dose-effect analysis indicate a need for further research.

The study had several important limitations. Because of data limitations, we were unable to address two common concerns about reducing seclusion and restraint: that it will result in increased injuries to patients and staff and that it will increase the use of PRN psychotropic medication as a substitute “chemical restraint” (

33,

34). The psychometric properties of the ISRRI were not formally tested, although several measures described above were taken.

The findings suggest several opportunities for further research. One is refinement of the ISRRI, such as conducting more formal psychometric testing and using the ISSRI to determine the relative impact of the individual domains and subdomains of the 6CS in order to identify core components and their relative importance (

35–

37).

Further exploration of differences in implementation patterns, including qualitative methods, would advance understanding of the barriers and facilitators that influence implementation. Also, the use of BHPMS measure specifications allows for the possibility of additional research—for example, analysis of differences among facility types and state mental health system characteristics or the relationship between implementation and outcomes at the unit level.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of the variety of approaches and tools represented by the Six Core Strategies for Reduction of Seclusion and Restraint for reducing the use of seclusion and restraint in diverse facility types and patient populations. All but two of 43 facilities succeeded in implementing evidence-based strategies to some extent, and most achieved some degree of reduction in seclusion and restraint rates. Differences among facilities in the degree of reduction were related to differences in the extent of implementation. Further research is required to understand the relative effectiveness of specific strategies and to gain a better understanding of the dynamic relationship between the implementation process and consumer outcomes across diverse types of facilities.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Data collection for this study was funded under task order 280-04-0103 from the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD). Measures from the Behavioral Health Performance Measurement System were licensed for this study by the NASMHPD Research Institute. The authors thank Noel Mazade, Ph.D., Gary Bond, Ph.D., the faculty of the National Executive Training Institute, and the staff of the participating facilities. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, opinions, and policy recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of CMHS, SAMHSA, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors report no competing interests.