Research has consistently shown that serving in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan increases risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), regardless of sample, measurement tool, combat exposure, or being physically wounded (

1). The prevalence rate of PTSD in this population is approximately 8% (

2–

4). Research has also documented poor recovery trajectories for veterans with PTSD symptoms (

5,

6), who may suffer from symptoms for as long as 20 years after their war experiences (

5).

Among service members who acknowledge mental health symptoms, only about one-quarter seek treatment (

7–

10). This low rate of treatment seeking remains true despite extensive outreach by the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. More disturbing is information suggesting that service members seeking services are unlikely to stay in treatment (

11).

Numerous trials have been conducted to determine the barriers to treatment among veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) (

7,

10,

12–

16). The emerging pattern indicates that returning service members do not wish to be perceived as weak (

7,

10,

16), and they worry about the consequences for their military position (

7,

10,

16). Individuals most in need of treatment are also those who report the most substantial barriers to seeking treatment (

12,

15). Research consistently reveals a pattern of attitudinal or cognitive barriers as well as system-level barriers that thwart meaningful treatment utilization (

17).

The unfolding story suggests that the prevalence of PTSD among returning service members is high, treatment utilization is low, and those who do seek treatment are unlikely to stay in treatment. Although it would be reassuring to know that those who make it to treatment and stay in treatment get good treatment, research suggests that they are unlikely to get minimally adequate treatment (

18,

19). Without adequate treatment, returning service members will likely continue to suffer from symptoms of PTSD throughout their lives.

The purpose of this randomized controlled trial was to test the effectiveness of a brief, cognitive-behavioral intervention, delivered by telephone, that was designed to modify beliefs about treatment seeking in order to improve PTSD treatment utilization. We hypothesized that, compared with participants in the control group, participants receiving the brief intervention would be more likely to initiate PTSD treatment, would attend more PTSD treatment sessions over the course of six months, and would have greater reductions in their symptoms of PTSD.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through visits to armories and through social media advertisements. Service members were eligible to participate in this study if they had screened positive for PTSD after deployment to Iraq, Afghanistan, or both and had not initiated PTSD treatment. Initial screenings for PTSD were conducted with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview–PTSD subscale (MINI) (

20). Participants who screened positive for PTSD and were interested in participating were informed fully of the study’s procedures and provided informed consent. This study was reviewed and approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College. This study lasted from November 2009 through August 2012.

Procedure

On enrollment in the study, participants were randomly assigned with the use of a randomization chart to either the intervention or control condition. Trained research staff administered the baseline assessment by telephone to all participants to assess demographic information, beliefs about PTSD treatment, and symptom severity. Intervention participants scheduled a time for the intervention session, and they received an additional phone call for this session. Participants in the control condition did not receive this intervention session. All participants received follow-up calls to assess service utilization, beliefs about PTSD treatment, and symptoms at months 1, 3, and 6 after the baseline assessment.

Measures

The Perceptions About Services Scale (PASS) assessed beliefs about PTSD treatment. The PASS is a 45-item self-report measure with items conforming to the theory of planned behavior (

21). Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher numbers reflecting more positive beliefs about treatment (from 1, strongly disagree, to 7, strongly agree). Examples of items on the scale include “Treatment will reduce symptoms,” “Some of my experiences would be too difficult to talk about in treatment,” and “Going to treatment means I can’t handle my problems.” Some items are reverse-coded for scoring. The PASS has adequate test-retest reliability and high internal consistency (

10).

We used the PTSD Checklist–Military Version (PCL) (

22), which is a reliable and valid 17-item assessment of PTSD symptoms (

23), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which is a reliable and valid nine-item measure of depressive symptoms (

24). In both cases, the total score represents overall symptom severity, with higher scores indicating greater severity.

To assess treatment utilization, all participants received follow-up phone calls at months 1, 3, and 6 after the baseline assessment. Participants were asked whether they had initiated treatment (by both scheduling and attending the appointment) and, if they had, the number of treatment sessions they had attended. Information regarding the treatment session was also gathered (for example, whether the appointment was at a VA or non-VA facility and whether the appointment was with a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other). We also assessed the type of treatment received (including cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], medications, or exposure therapy).

Intervention sessions

Participants in the intervention group received one intervention session within a week of the baseline assessment. The session was administered by telephone by a psychologist and lasted approximately 45–60 minutes. The sessions were based on CBT principles, which posit that thoughts, feelings, and behaviors interact with each other in predictable ways (

13). Because thoughts are modifiable, changing thoughts about situations may change behavior in those situations. For example, the thought “I don’t need treatment” might become “I might need treatment considering how hard it is to sleep and the impact it is having on my relationships and job” or “I am drinking a lot to avoid thinking so maybe treatment could help me deal with my memories better.” Participants identified individual beliefs about treatment during the intervention session. The intervention session addressed a maximum of three beliefs with each participant.

Statistical analyses

Means and frequencies described the characteristics of the sample, and t tests and chi square tests examined differences between the two groups at baseline. Logistic regression was used to compare the two groups for differences in treatment initiation at each follow-up point, which provides the same result as a chi square test but also provides the regression coefficient. Because treatment utilization—that is, the number of treatment sessions attended—was a count variable that is positively skewed, the negative binomial model assessed group differences in the cumulative number of treatment visits at each follow-up point. Generalized estimating equation models with the normal distribution and the identity link were used for longitudinal analysis of PTSD and depression symptom severity. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.3. A p value of .05 was used throughout to indicate statistical significance.

Results

A total of 475 individuals completed the PTSD screening assessment; 300 eligible individuals provided informed consent and were enrolled in the trial. Of the 175 individuals who did not meet eligibility criteria, 63 were already in treatment, 76 did not screen positive for PTSD, and 36 were not eligible for other reasons (including that they were not OEF/OIF veterans). Of the 300 enrolled participants, 143 were randomly assigned to the intervention condition, and 157 were assigned to the control condition. Twenty-six participants (20 in the intervention condition and six in the control condition) withdrew or were withdrawn from the study after baseline assessment, leaving a total of 274 participants. Thirty-six participants were lost to follow-up (14 in the intervention arm and 22 in the control arm). We removed from the analytic data set participants who withdrew from the study, leaving a total of 123 participants in the intervention group and 151 participants in the control group.

A majority of the participants were male (87%) and Caucasian (69%), with a mean age of 29 years (

Table 1). The only significant difference between groups was in age; the intervention group was younger than the control group (28.3 versus 30.2). Both groups reported moderate to moderately severe symptoms of PTSD and depression at baseline.

A clear pattern emerged regarding treatment engagement during the trial (

Table 2). Our eligibility criteria established that participants had no PTSD treatment engagement at baseline. At the one-month follow-up, a majority of participants continued to resist seeking PTSD treatment, although participants who received the intervention were twice as likely as control participants to seek treatment (χ

2=3.85, df=1, p<.049; odds ratio=2.08, 95% confidence interval=1.01–4.31). At the three-month follow-up, approximately one-third of both groups reported seeking treatment for PTSD, although the difference between groups was not significant. At the six-month follow-up, rates of treatment initiation continued to rise for both groups and did not differ significantly.

A similar pattern emerged for the number of PTSD treatment sessions attended (

Table 2). Whereas most participants attended no sessions of PTSD treatment in the first month of participation, those who did attend reported going to only one session, resulting in low overall rates of attendance and no difference between groups. At the three-month interview, the number of PTSD treatment sessions attended remained low and not significantly different between the two groups. At the six-month follow-up, intervention participants reported attending a significantly greater number of treatment sessions than the control group participants (χ

2=4.09, df=1, p=.043).

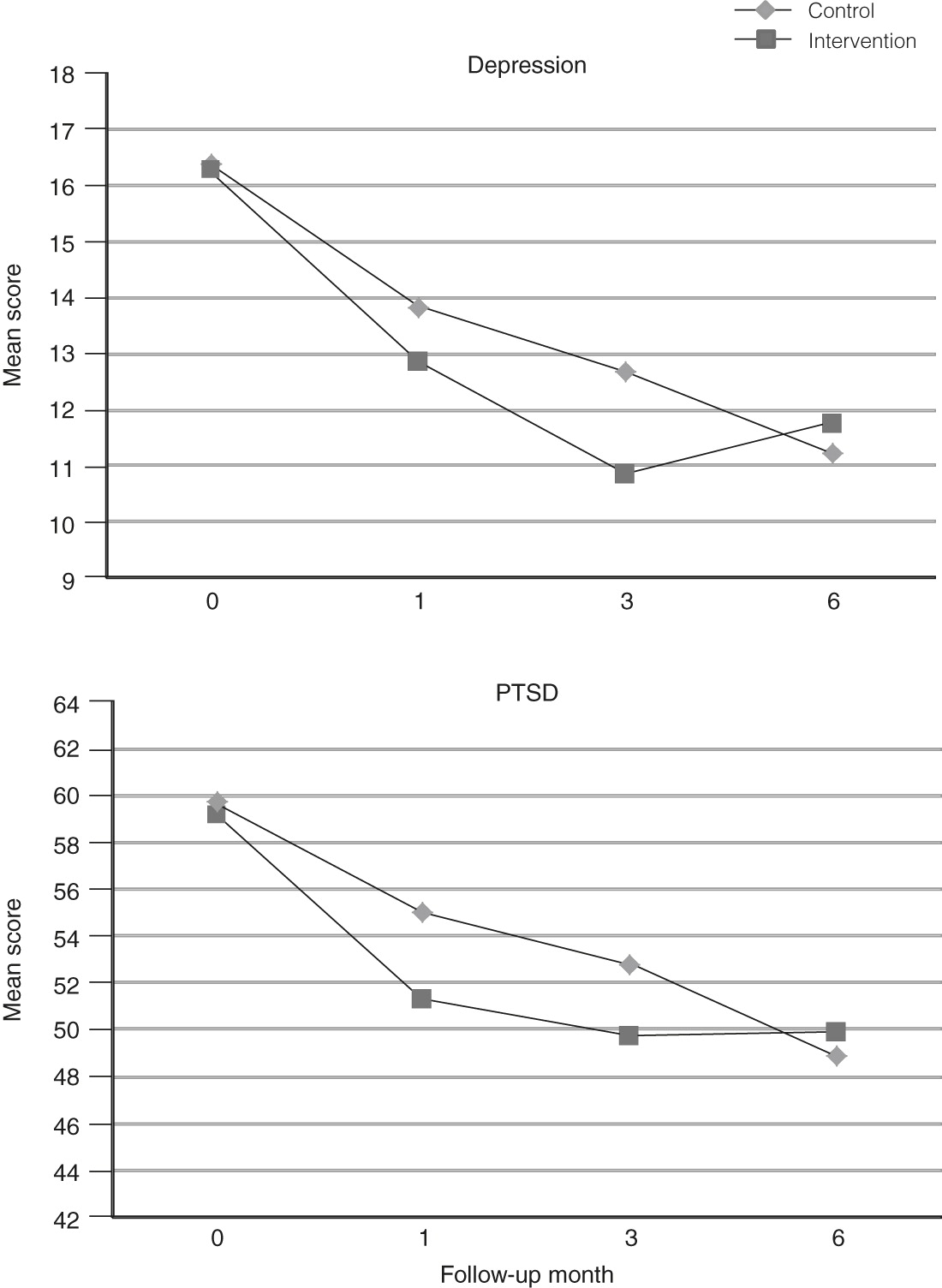

Participants in both groups reported significant reductions in symptoms of both PTSD and depression during the course of the six-month trial (

Table 3). Symptoms of PTSD diminished among intervention participants from a mean PCL score of 59.2 out of 85 at baseline to 49.8 at the six-month follow-up. Participants in the control group reported comparable reductions in PTSD symptoms, with a mean PCL of 59.7 at baseline and a mean of 48.9 at the six-month follow-up. Because of the nonlinear nature of the changes in symptoms over time, we conducted a piecewise regression analysis, where the first piece was from baseline to the three-month follow-up, and the second piece was from the three-month follow-up to the six-month follow-up. Longitudinal analysis indicated a nonsignificant group × time interaction for the first piece, although the intervention group showed more reduction in PTSD symptoms. A significant group × time interaction was found for the second piece, reflecting the crossover of the two groups between the three- and six-month follow-ups (coefficient=4.69, p=.004). Whereas both groups reported reductions in PTSD symptoms during the early course of the trial, intervention participants reported reductions earlier. Participants in the control group reported continued reductions from months 3 through 6, whereas intervention participants reported no further reductions.

A similar pattern emerged for symptoms of depression (

Table 3 and

Figure 1). Mean PHQ-9 scores for intervention participants decreased from 16.3 at baseline to 11.8 at the six-month follow-up point. Mean PHQ-9 scores for participants in the control group improved from a mean of 16.4 at baseline to 11.2 at the six-month follow-up. Piecewise longitudinal regression analysis revealed a significant group × time interaction for changes in symptoms of depression from baseline to the three-month follow-up (coefficient=–.856, p=.026) and a significant interaction from the three- to six-month follow-ups (coefficient=2.361, p<.001). The pattern for depression symptoms was similar to the pattern for symptoms of PTSD; the intervention group showed more change for the initial period but less change for the latter period.

Analysis of covariance assessed the impact of PTSD treatment utilization on symptoms of PTSD at the end point and controlled for baseline PTSD symptom severity. We had hypothesized that participants who received treatment, regardless of experimental condition, would have fewer and less severe symptoms than those who did not receive treatment. Attending PTSD treatment during the six-month study was not associated with lower PTSD symptoms.

Discussion

Our brief, telephone-based, CBT intervention accelerated treatment utilization and symptom reduction among OEF/OIF veterans who screened positive for PTSD and who had resisted treatment. Participants receiving the intervention were likely to get to treatment sooner than participants in the control condition. Likewise, participants receiving the intervention attended more PTSD treatment sessions than participants in the control condition during the six-month study period. The intervention used in this study was “low dose” in that it consisted of only one hour of intervention, conducted by telephone with a psychologist. Adding follow-up sessions might improve the rate of treatment initiation and attendance beyond that found in this trial. Results of this trial are consistent with other literature assessing interventions to increase psychotherapy attendance (

25).

This is one of very few studies that have focused on military populations that are not currently enrolled in mental health care offered through the Veterans Health Administration or the U.S. Department of Defense. Much of the current work of these entities focuses on improving rates of mental health treatment utilization among patients already being seen in primary care (

26,

27). In this trial, success was dependent on the individual’s attending PTSD treatment and being able to navigate enrollment into the VA system. Likewise, this is one of the only trials that has focused on using cognitive-behavioral strategies with military populations to improve treatment utilization. Other trials have used motivational interviewing to improve treatment utilization among patients already enrolled in VA care. One potential benefit of using cognitive-behavioral methods is that with large enough samples, beliefs about treatment could be coded and tested to see if a change in belief predicted the behavior of initiating PTSD treatment. Testing models of belief change would provide evidence as to whether individual perceptions drive the decision of whether or not to seek treatment.

We hypothesized that participants who received the intervention session would have greater reductions in symptoms over the course of the six-month study than participants in the control condition. Yet both groups showed similar reductions in symptoms of PTSD and depression over the course of the study. Although PTSD treatment attendance was hypothesized to result in greater symptom reduction, the results indicated that treatment attendance was not associated differentially with symptom reduction. Further research is needed to help understand this PTSD treatment response.

Several factors have been associated with the decision to seek treatment within military populations. Many veterans have identified an unwillingness to seek treatment because they do not want to be prescribed medications (

28,

29). Stigma has also been identified in the literature as influential in the decision (

30,

31); however, participants in this study only infrequently identified stigma as an issue during intervention sessions (

29). The most influential cognitive predictors of treatment utilization may be perceived symptom severity and avoidance discussing the traumatic event (

29).

This study was limited in that it focused on only the cognitive barriers to treatment seeking for PTSD. Other barriers—including distance to a VA facility, although that was not a significant covariate in our outcome analyses—may be involved in the decision to seek treatment. Although these practical barriers are often cited as limiting treatment engagement, ultimately it may be an individual’s perceptions of these barriers that drive the decision of whether or not to seek care. Another limitation of this study was that substance use was not measured within this trial, and it may have been involved in decisions to seek treatment.

This study was also limited because treatment utilization was assessed by self-report. Self-report measures of treatment utilization were the only practical method of attaining this information. Almost half of the sample reported that they never had a treatment visit, and many accessed treatment in non-VA settings. Having a self-report measure allowed us to gather data on individuals outside of the VA setting.

Twenty-six participants withdrew from the study (20 in the intervention condition and six in the control condition) after the baseline assessment. A higher level of withdrawal may have occurred in the intervention condition from participants who were avoiding an “intervention session.” Avoidance behavior is common among individuals suffering symptoms of PTSD, and this avoidance may have been demonstrated through a higher withdrawal rate among participants in the intervention condition.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a one-time brief telephone intervention engaged service members in PTSD treatment earlier than conventional methods and led to immediate symptom reduction. There were no differences at the longer-term follow-up, suggesting the need for additional intervention to build on initial gains. Additional intervention could include a booster session that occurs at two weeks or one month subsequent to the initial intervention session. This additional session could bolster the individual’s intention to seek or to stay in PTSD treatment and would allow for continued use of coping skills or even allow service members to continue to explore the meaning of the trauma experienced.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by a grant funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, R01 MH086939.

The authors report no competing interests.