Over the past two decades, considerable attention has been directed toward the increasing prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (

1). ADHD, characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, is an early-onset neurodevelopment disorder affecting approximately 5.3% of children worldwide and 7.5% of children in Taiwan (

2,

3). Among U.S. preschoolers, the prevalence of ADHD is estimated to be between 2.0% and 5.7% (

4). A pioneer three-year study that followed U.S. children ages four to six with a diagnosis of ADHD found that most still met full diagnostic criteria after they entered elementary school, suggesting stability of the diagnosis in early childhood (

5). ADHD symptoms that occur in childhood may persist into adolescence and even adulthood (

6). Children with untreated or ineffectively treated ADHD often experience academic and social difficulties (

7–

9). Although several adverse outcomes related to untreated ADHD have been reported, less than one-third of children with ADHD receive health care services, according to an Australian study (

10).

Medication and psychosocial therapy are two of the most widely recommended treatment approaches for children and adolescents with ADHD (

11–

16). Currently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the United Kingdom recommend that medications for ADHD, including methylphenidate and atomoxetine, be used only with children age six and older. Nevertheless, the number of U.S. preschoolers with ADHD receiving methylphenidate has increased over the past decade (

17,

18). Initial evidence has indicated that stimulants (methylphenidate) are effective for the treatment of young children with ADHD (

19). However, a recent report indicated that psychosocial therapy is more effective than medication (

20), and the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended psychosocial treatment as a first-line treatment for preschoolers with ADHD (

21).

A number of studies, mostly using cross-sectional designs, have identified important factors affecting treatment of young children with ADHD, such as sociodemographic characteristics (for example, age, gender, and race-ethnicity) and clinical history (for example, comorbid mental disorders) (

22–

27). However, these studies generally focused on medication treatment (

22,

24,

26,

27). Family characteristics beyond the issue of health insurance status (for example, family structure) await exploration. Because pharmacological treatment is recommended only for children age six and older, the rapid growth of preschoolers with a diagnosis of ADHD heightens the urgency to better understand factors affecting the use of nonpharmacological treatments.

In addition, a small but growing body of literature addresses the roles of health service providers in delivering services to children with mental health problems, including ADHD (

27–

29). For example, a survey of primary care pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists found specialty-related variation in pediatricians’ perceived responsibility to identify, treat, and refer children with ADHD (

29). Nonetheless, these studies did not directly investigate the association between continuity of care and physician and practice characteristics related to treatment options.

We sought to address gaps in previous studies in regard to the potential effects of socioeconomic and service provider factors on the multiphase process of identifying medical needs, making treatment decisions, and obtaining continuous health care by examining data from a cohort of preschoolers who had recently received an ADHD diagnosis. We examined whether family socioeconomic characteristics and provider-level factors explain differences in initial treatment status and treatment mode among children in Taiwan’s universal health insurance program. We also looked at one-year utilization patterns.

Methods

Data Source

This study used 2001–2007 data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan. The database is derived from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Program (NHIP), which has provided comprehensive medical care coverage to all civilian residents since 1995. The database is maintained by the National Health Research Institute (NHRI) for research purposes. The 2004 coverage rate for individuals younger than 19 years was estimated at 98.7% (

30). Each beneficiary has a unique encrypted identification number in the NHIRD that links all insurance information and health care records. Because referrals are not required, beneficiaries who contribute different registration fees and copayments can access health care providers of any specialty or at any medical institution level. The NHRI’s institutional review board approved this study.

We used a retrospective longitudinal design. The original sample included children born between 2001 and 2003 who were initially given a diagnosis of ADHD (ICD-9-CM code 314.XX) between the ages of three and five (from 2004 to 2006) (N=7,196). To accurately diagnose ADHD among preschoolers, careful clinical and diagnostic assessments and behavioral observations, which may require two or three outpatient visits, are necessary. To ensure the validity of diagnoses, the study included only patients who had at least two outpatient visits for ADHD in a six-month period after the initial diagnosis. Thus the final sample included 3,583 children, whose health care records from birth through one year after the initial ADHD diagnosis were retrieved.

Measures

Information on individual demographic (for example, gender, age, and region), clinical, and socioeconomic characteristics was obtained from the beneficiary registry data files. History of mental disorders was categorized as positive if before the initial ADHD diagnosis, the child had received a mental disorder diagnosis other than ADHD (

ICD-9-CM code 290–316, excluding 314.XX). Several major mental disorders were individually specified, including autism (299.0X), mental retardation (317, 318.0, 318.1, 318.2, and 319), and developmental delay (315.XX). History of catastrophic physical illness (for example, congenital deficiency and cerebral palsy), as defined by the NHIP, was also assessed from birth onward. Since the NHIP premium was income based during the study period, we grouped insurance premium into four levels (high income, middle income, near poor, and poverty), which served as a proxy measure for the child’s socioeconomic status (

31). The person designated as “primary insured” was recorded (father, mother, or other) as the employed individual responsible for the child’s insurance. The insured individual’s residential urbanicity was documented as a measure of health care resource accessibility.

Medical institution and physician were two major service provider variables. First, we classified all medical institutions into four categories according to specifications of the Hospital Accreditation System of Taiwan. Specialist physicians, such as psychiatrists, pediatricians, physiatrists, and others (for example, family medicine specialists), were identified, and data were separately retrieved. In the NHIP, physiatrists can provide care by prescribing medications (for example, methylphenidate) and providing alternative therapy (for example, sensory integration training or physical exercise training) for ADHD treatment (

32,

33). For each child, ADHD service volume for diagnosing physicians was defined on the basis of the percentage of ADHD visits in the calendar year before the initial diagnosis. A similar measure was created for the physicians who provided initial treatment. Change of physician was noted in cases when a preschooler had received the ADHD diagnosis from two or more physicians during the first three visits.

ADHD treatment was first categorized in two ways: medication and nonmedication. During the study period, methylphenidate was the only ADHD medication covered by the NHIP. Reimbursed nonmedication treatment included psychotherapy (for example, behavior modification, supportive psychosocial psychotherapy, and family therapy) and rehabilitation therapy (for example, physical exercise, sensory integration training, and occupational therapy). On the basis of health care received in the two months after the initial diagnosis, initial treatment mode included none, medication treatment only, psychosocial treatment, rehabilitation treatment only, and combined treatments (both medication and nonmedication treatment). For any treatment mode, termination was defined as occurring when a child did not receive treatment for 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for family, clinical, and health care provider variables were first calculated by cross-tabulation. The association of initial treatment status and mode with family and health care provider variables was assessed by using binary and multinomial logistic regression analyses. Next, we used Kaplan-Meier survival curves to estimate the cumulative probability of treatment retention among children who initiated treatment within two months of receiving the initial ADHD diagnosis, with the log-rank test to examine differences in survival functions across the four major treatment modes in Taiwan. Finally, to investigate factors associated with treatment termination, we used a Cox proportional hazards model. The addition of a new treatment (that is, the add-on treatment) was treated as a time-varying covariate in the final model. All tests were two-sided, and an alpha value of .01 was used to reduce the risk of type I error. The data were prepared and the analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 software.

Results

Table 1 presents data on selected individual and service provider characteristics of young children with ADHD. More than three-quarters of the children were from middle- or high-income families, and nearly 60% were insured under their working fathers. Most children received the initial ADHD diagnosis from physiatrists and psychiatrists (58% and 32%, respectively) and at a medical center or regional hospital (31% and 32%, respectively).

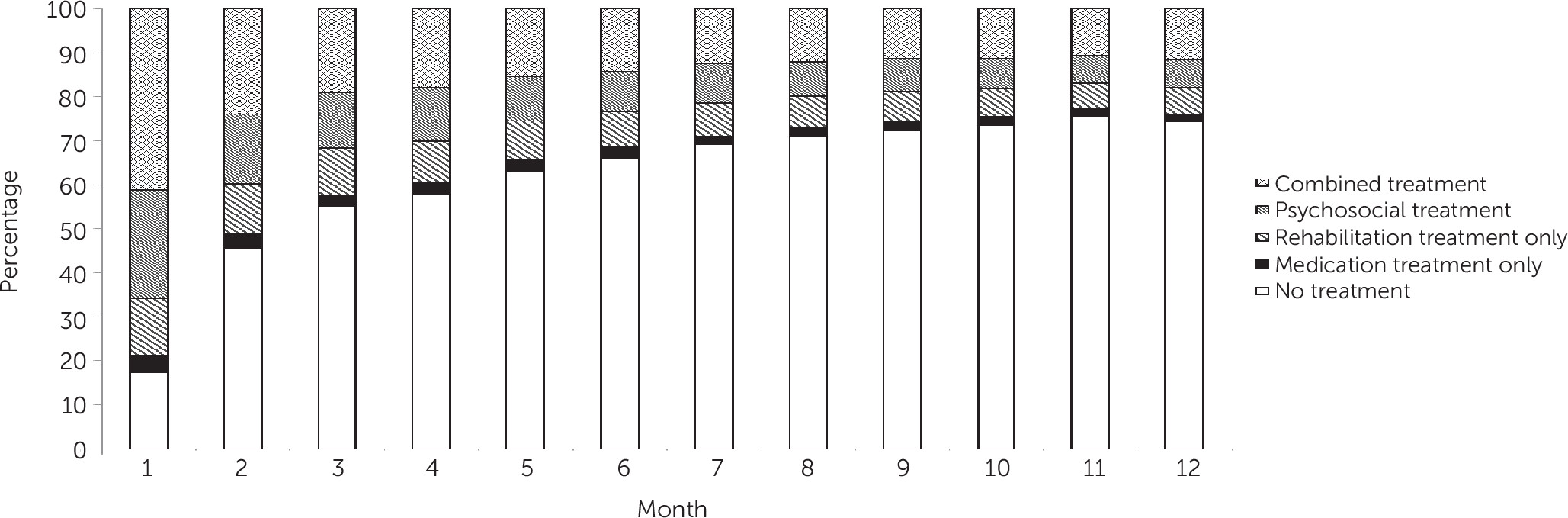

Over half of the children were not receiving treatment at the end of the third month after the initial diagnosis (

Figure 1). The decline in treatment use reached a plateau at nine months after the diagnosis. Only 11.6% were still receiving combined treatment at 12 months, similar to the proportion receiving nonmedication treatment (psychosocial and rehabilitation only) (12%).

When the main confounders were adjusted simultaneously, results indicated that none of the socioeconomic characteristics examined was associated with initial ADHD treatment status or treatment mode (

Table 2). Two factors were associated with increased ADHD treatment initiation: receiving the first diagnosis from a psychiatrist or pediatrician (adjusted odds ratios [AOR]=3.95 and 44.52, respectively, p<.001) or from a high-level hospital (district hospital, AOR=3.02; regional hospital, AOR=13.29; and medical center, AOR=11.17; p<.001). Among children who received treatment within the first two months (N=3,012), those who received the initial diagnosis from a psychiatrist were 1.6 times more likely to initiate combined treatments and less likely to receive medication treatment only (AOR=.17, p<.001) or rehabilitation treatment only (AOR=.02, p<.001), compared with peers receiving psychosocial treatment.

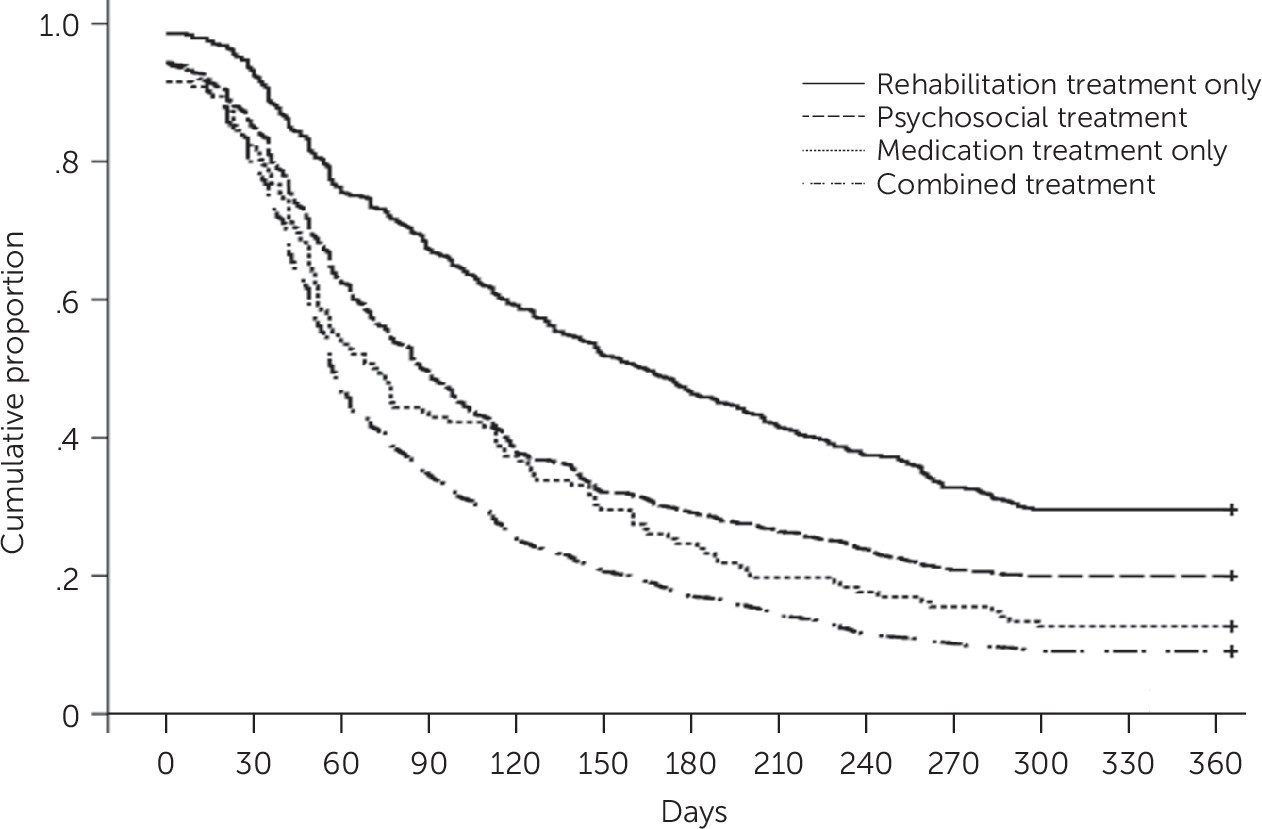

For children who received rehabilitation treatment only (

Figure 2), approximately 45% remained in such treatment at the end of six months. The corresponding estimates for psychosocial treatment, medication treatment only, and combined treatment were 29%, 25%, and 17%, respectively. The observed patterns of treatment retention differed significantly by mode at 12 months after treatment initiation (log-rank test, p<.001).

Predictors of treatment termination at one year varied by treatment mode (

Table 3). For combined treatment, children from families in poverty (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR]=1.72, p<.05) or from a rural region (AHR=1.40, p<.05) tended to terminate treatment more quickly. For psychosocial treatment, receiving initial treatment from a psychiatrist increased the likelihood of treatment termination (AHR=1.80, p<.001). For rehabilitation treatment only, receipt of initial treatment from a physician with higher ADHD service volume increased the likelihood of treatment termination (AHR=3.02, p<.001). Having a history of other mental disorder lowered the likelihood of early treatment termination (AHR=.6, p<.001).

Discussion

Three major findings emerged from our study of a population-based cohort of 3,583 young children in Taiwan who had recently received a diagnosis of ADHD. First, over 80% of the children received treatment within a month of the initial diagnosis, and more than half of the treated children received combined treatments. Second, children who received the initial diagnosis from a physician with a specialty in psychiatry or pediatrics or at a high-level medical institution were more likely to start treatment within the first two months of diagnosis. Finally, the one-year termination rate was lowest for children who received rehabilitation treatment only. Predictors of treatment termination differed by treatment mode; by and large, the role of health care providers appeared more salient than that of family socioeconomic status.

The first year after the initial diagnosis has been identified as critical in terms of early intervention and treatment (

21). Effective intervention can not only reduce ADHD-associated social and learning problems, but it can also provide optimal opportunity to improve developmental outcomes (

14). In this study of preschoolers, we found that nonmedication treatment (alone or in combination with medication) was more common than prescription of stimulant medication as the initial treatment. In previous studies (

34), the age ranges and clinical profiles (for example, ADHD severity and comorbid mental disorders) of the children may have differed from those in our sample. In addition, medical professionals’ recommendations and cultural or societal variations in parental preferences in regard to ADHD treatment may explain the lower use of medication in our study (

32,

35).

Our estimate of use of stimulant medication as the initial treatment (approximately 45%) is generally consistent with rates in prior cross-sectional studies (

25,

34). However, the proportion of children receiving methylphenidate in our study dropped to 17% at six months after the initial diagnosis (14.2% for combined treatments plus 2.5% for medication only), our estimates of stimulant use were lower than in previous reports. The relatively lower rates of treatment continuity probably resulted from the limited availability and accessibility of pediatric developmental care in primary care settings, because almost 50% of the children in the study had received their initial diagnosis at a medical center. Other reasons may include caregivers’ lack of information about ADHD treatment, concerns regarding the stigma of ADHD, perceived benefit of treatment, and relatively low school adjustment stress (

32,

36,

37).

In contrast to prior research (

22,

24), our findings suggest that neither urbanicity nor family income was related to the initial treatment received or to treatment retention. Such discrepancies may result from differences in sample characteristics associated with insurance eligibility (for example, U.S. Medicaid versus the Taiwan NHIP) and coverage for ADHD treatment (

25,

34). Another plausible explanation is that the case definition of three or more outpatient visits for ADHD in this study may have limited our sample to children with similar socioeconomic status or medical conditions. Finally, regardless of treatment mode, the add-on treatment had no effects on retention, indicating that for preschoolers with ADHD in Taiwan, sequenced treatment alternatives are either uncommon (most started with combined treatment) or are adopted at the end of the treatment course. The former explanation is also supported by the observation that the treatment shift rate was lower than rates reported in prior research (

25).

Our analysis demonstrated that the specialty of service providers played a significant role in both treatment initiation and termination. Specifically, receiving the initial ADHD diagnosis from pediatricians or psychiatrists may increase the likelihood of treatment initiation; however, receiving initial treatment from psychiatrists was associated with a more rapid termination of psychosocial treatment, medication treatment only, and combined treatment. This seemingly paradoxical observation may be partially explained by specialty-related variation in the practice guideline for treatment of children with ADHD and in awareness of and adherence to clinical guidelines in treating children with psychotropic medication (

12,

38). For example, given the fact that the course of psychosocial treatment for children with ADHD (for example, family therapy or behavioral consultation) often lasts no longer than six months in Taiwan, the rapid termination in psychosocial treatments related to receiving treatment from a psychiatrist may simply reflect treatment completion.

Of note, the ADHD service volume of health care providers also had an effect on the initial treatment option and long-term treatment retention. Among children who initiated treatment, receiving the diagnosis from a physician with a higher ADHD service volume was associated with an increased likelihood of medication treatment. However, receiving rehabilitation treatment from a physician with a higher ADHD service volume also led to more rapid termination. This observation may have resulted from differences in patient profiles associated with treatment indication or option (for example, ADHD severity), or it may have been the result of limited availability of outpatient appointments for nonmedical treatments or limited appointments resulting from high ADHD service volume.

We found that receiving the initial diagnosis from a higher-level medical institution was generally associated with greater odds of initiating treatment. The results remained robust after statistical adjustment for individual and clinical characteristics, suggesting a greater gap in accessing specialist pediatric mental health care (for example, clinical psychologists) in primary care clinics, and may highlight the need to improve access to specialist treatment in local communities (

39). Finally, among young children who received initial treatment, the observed differences in treatment mode by medical institution level may be partly explained by the variation in the referral network and by the expertise and specialties of medical team members.

This study had several limitations. First, because our analyses were based solely on NHIP data sets, children whose treatment or health care was paid for out of pocket or by government funding (for example, early intervention programs) were not included, which may have led to an underestimated treatment rate. Another limitation was the lack of clinical validity of ADHD diagnoses. The criterion of three or more outpatient visits that we adopted to enhance clinical validity may have introduced some bias. To illustrate, post hoc analyses indicated that children who were excluded from the study because they had fewer than three visits tended to have a lower premium (p<.001), suggesting that the children in our study may have come from families of relatively advantaged socioeconomic status. For sensitivity analyses, we repeated the series of analyses with patients who had at least one outpatient visit after the initial ADHD diagnosis (N=5,172); the results were generally similar in terms of direction and magnitude of the association.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the study is among the first to investigate ADHD treatment options in a preschool-age population. In addition, having a large, nationally representative sample allowed us to explore treatment options more closely. Analyses that consider changes in treatment options over time may provide a unique opportunity to evaluate clinical characteristics (for example, hospital-level factors and specialty of the physician making the initial diagnosis) from a long-term perspective. Finally, our focus on incident cases may have reduced susceptibility to bias resulting from reciprocal relationships (for example, certain clinical characteristics may change as a result of ADHD treatment). In addition, the nature of the longitudinal follow-up in this study helped establish a temporal sequence for observed association.

Conclusions

This population-based longitudinal study demonstrated an unmet health care need among young children with ADHD in Taiwan. Our findings reinforce the importance of developing consensus across specialties regarding diagnosis, management, and referral in the preschool-age population with ADHD. To ensure that children receive high-quality continued treatment for ADHD, community-based comprehensive and coordinated pediatric developmental care should be considered to address the medical and social welfare needs of children with ADHD and their families (for example, medical homes) (

40). Additional research is needed to identify organizational structures and insurance mechanisms that drive specialty-related differences in health care–seeking processes.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by NHRI (98A1-PHPP44-021) and a grant from the Ministry of Education, Aim for the Top University Plan. NHRI had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication. The authors thank the individuals who manage the NHIRD in NHRI’s Department of Research Resources.

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.