In 2009, the Center for Practice Innovations at Columbia Psychiatry and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (CPI) (

1) began providing training and implementation supports to New York State behavioral health practitioners to implement integrated treatment for people with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. The size of the state and the number of providers made this challenging, and thus CPI turned to distance technologies.

Distance technologies may be at least as effective as face-to-face training (

2). CPI collaborated with key stakeholders and content experts to create online training and distance supports focused on providing integrated treatment. Learning collaboratives (

3) have been used to disseminate evidence-based practices in general medical care and behavioral health care (

4,

5). Traditionally, learning collaboratives have relied heavily on face-to-face sessions, supplemented by teleconferences and Web-based discussions. This report describes experiences and outcomes among programs participating in a learning collaborative accessed solely through distance technology.

Methods

New York State’s Office of Mental Health developed a statewide program model in 2004 comprising recovery-oriented evidence-based practices. In March 2012, 12 of these Personalized Recovery Oriented Services (PROS) programs volunteered for a year-long learning collaborative focused on the implementation of one component of integrated treatment, stagewise treatment. Stagewise treatment posits that change is a process, that people go through a series of stages in changing any behavior, and that the treatment provided must be appropriate to the person’s stage (

6). One program withdrew after a temporary shutdown and relocation.

Participating programs agreed to have at least two staff members join monthly online, 90-minute meetings for 12 months. CPI led the online meetings, providing tools and consultation to support implementation of stagewise treatment and facilitating discussion of progress and challenges in meeting implementation goals. CPI encouraged person-to-person interaction in the online meetings through features such as polling questions, a chat box, and discussion notes. Between meetings, programs agreed to create implementation work groups consisting of the two learning collaborative participants and at least one stakeholder, such as a consumer or quality improvement director. Work groups engaged all program staff to develop skills and procedures that facilitated implementation of stagewise treatment by creating an implementation plan, overseeing the work toward the plan’s goals, and collecting and submitting performance indicator data. The New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board determined that this evaluation did not meet the definition of human subjects research.

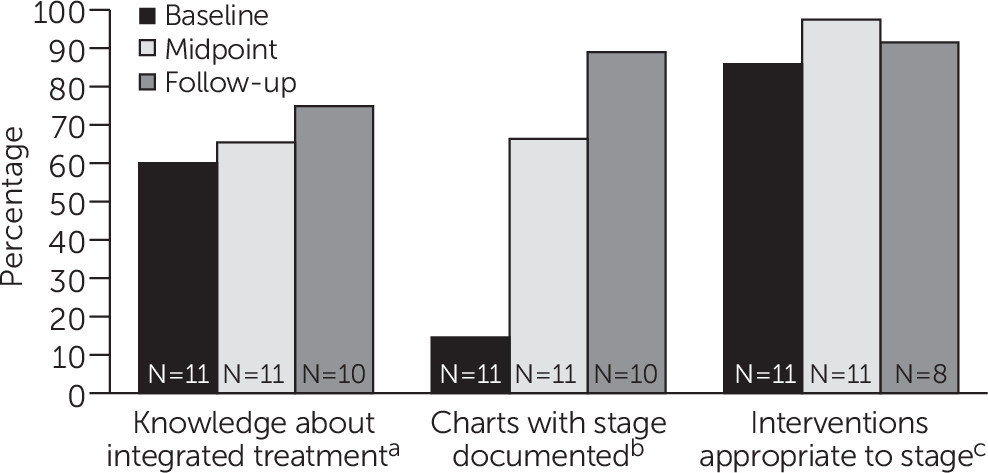

The learning collaborative collected three performance indicators at baseline (spring 2012), midpoint (fall 2012), and follow-up (spring 2013). The first assessed all program staff’s knowledge of integrated, stage-based treatment as measured by the percentage of correct responses on the Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment Knowledge Survey (

7). The second was whether clients’ current stages of treatment were documented in their charts. To measure this, PROS staff audited ten consecutive charts of individuals identified by program staff as having co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. To select charts, CPI staff randomly chose a different letter of the alphabet at each time point. Program staff then started with that letter and evaluated ten consecutive charts drawn from all program charts and reported whether the person’s stage of treatment (engagement, persuasion, active treatment, and relapse prevention) was documented. The indicator was reported as the percentage of charts with a stage of treatment.

The third indicator was whether the treatments listed in an individual’s treatment plan were appropriate for the stage of treatment. Again, program staff identified charts of individuals who had a co-occurring disorder and who had a last name beginning with an arbitrary letter selected by CPI staff, different at each time point. Working backward, staff were instructed to choose the first person with co-occurring disorders, noting his or her stage of treatment and the interventions provided as documented the treatment plan. Continuing backward, staff identified the next three people whose stage of treatment matched one of the three remaining stages, until all four stages were matched. Staff noted interventions provided as documented in the treatment plan for all four people. A consultant external to CPI with expertise in co-occurring disorders scored whether the interventions were appropriate for the stage of treatment. One author (FF) reviewed the consultant’s ratings and resolved any questions by discussion with the consultant. For each program, we calculated the total percentage of treatments appropriate for the documented stage (total number of appropriate interventions across charts divided by the total number of interventions across charts multiplied by 100).

All 11 programs provided complete baseline and midpoint performance indicator data. For the final time point, one program did not submit any data for any indicator, and two programs submitted data for only the first two indicators. All three programs experienced significant changes in leadership prior to final data collection. We also asked program staff to complete a brief survey at the conclusion of the learning collaborative to assess how various aspects of the collaborative supported implementation of stagewise treatment in their programs and to elicit strategies for sustaining the change.

Using SPSS, version 21, we applied descriptive statistics to characterize performance indicators over time and summarize feedback. Because data were not normally distributed and measures were repeated, we applied the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test at the program level to examine changes in performance indicators over time.

Results

One program was represented by two staff members at all 12 meetings. Programs were represented by at least one person at an average of 10.4±1.6 meetings (range of seven to 12 meetings).

Staff improved their knowledge of integrated treatment significantly over time (

Figure 1). The percentage of charts in which stage of treatment was documented increased significantly at midpoint and again at follow-up. The percentage of treatments that were appropriate for an individual’s stage of treatment increased significantly from baseline to midpoint. Notably, this indicator demonstrated a high baseline value (mean±SD=86%±22%, median=93%). Nevertheless, eight programs experienced additional gains over time. The performance of the remaining three programs declined at the follow-up after an initial improvement. Because only eight of the 11 programs submitted final data for this indicator, these three programs had more influence on the final average. All programs demonstrated some improvement over time; however, staff from the two programs that improved least attended fewer meetings (seven and nine meetings, respectively), and the two programs reported significant staff turnover.

Eight individuals from seven programs provided feedback. All reported that the information and support from CPI were helpful (five individuals [63%] endorsed very helpful), that sharing and hearing from other programs about how they implemented the practice were helpful (three [38%] endorsed very helpful), that the implementation model (identifying targets for improvement, selecting and tracking performance indicators, and creating a plan of action) was helpful (five [63%] endorsed very helpful), and that strategies for supporting implementation (online training, role playing, supervision and coaching, and changes in documentation) were helpful (four [50%] endorsed very helpful). Also reported as helpful were support received from CPI between meetings (six [75%] endorsed very helpful) and use of performance indicators to measure success (four [50%] endorsed very helpful). All eight individuals reported that the changes they implemented would help consumers meet recovery goals (three [38%] thought the changes would help a lot, and five [63%] endorsed somewhat). In an open-ended question, five (63%) reported that what they liked most about the collaborative was a sense of community and learning from other programs. During a one-year follow-up telephone call, one participant summarized the experience as follows: “These learning collaboratives . . . help us find a place to focus and see measurable results and be able to share that with the team. Thank you for opportunity to come together and to be real about implementation.”

Programs reported a variety of strategies to sustain the changes that they had made during the collaborative. Most programs developed policies and documents to incorporate staging of people into the assessment process and treatment plans. Several also reported regularly discussing a person’s stage and targeted treatments during case presentations. One program created an agencywide best-practice integration team to coordinate evidence-based implementation efforts across the agency. Another developed a dual recovery work group to provide continuous oversight of services, ongoing education, and ongoing staff support.

Discussion

Programs volunteered for an online learning collaborative and actively worked toward improving the implementation of stagewise treatment. Meeting exclusively online, program staff were able to develop a cohesive group, learn from one another, and work collaboratively toward goals. As the learning collaborative progressed, program staff demonstrated significant improvement in knowledge of integrated treatment and documentation of stage of treatment.

At baseline, program staff were already proficient in matching interventions to a person’s stage of treatment. Even with this high baseline proficiency, they continued to make gains through the middle of the collaborative. Although the final measure for this performance indicator did not differ significantly from the baseline or the midpoint, it is important to note that program staff remained highly capable of matching interventions to a person’s stage of treatment. Programs were also able to identify and implement strategies to sustain the changes that they made.

Although program staff reported that all components of the learning collaborative were helpful to some degree, support received from CPI staff between meetings, information and support from CPI staff during meetings, the implementation model, strategies to support the implementation model, and use of performance indicator data to demonstrate change were the most highly rated. In addition, what the individuals who provided feedback liked most was the sense of community and learning from other programs.

Several considerations limit generalizability. The number of participating programs was purposefully small. Nevertheless, we were able to document significant changes in performance indicators. The collaborative focused on one topic with one program type; it is unclear whether an approach using distance technology would be successful for other topics or programs. Because limited resources created the need for using distance technology, we were unable to visit programs to verify implementation. There was attrition in collection of performance indicator data at the final time point, which occurred after the final learning collaborative meeting. Future collaboratives may avoid such attrition by ensuring that all data are collected while the collaborative is actively meeting. Because data on performance indicators were collected at discrete times rather than continuously, timing of data collection may have influenced the results. Finally, lack of resources prevented us from conducting a learning collaborative with face-to-face meetings; thus we cannot contrast the distance learning collaborative with a more traditional approach. Future studies should examine whether distance learning collaboratives are successful for other topic areas and program types and should contrast the distance approach with more traditional face-to-face approaches.

Conclusions

In geographically large areas where face-to-face meetings are not feasible, it is possible to create successful learning collaboratives by using interactive online technology. Distance collaboratives can be structured in a way that still provides opportunities for programs to interact and to learn from one another, and programs can implement and sustain changes. Programs experiencing significant staff turnover may require additional supports to implement and sustain changes; lower attendance at learning collaborative meetings may indicate which programs would benefit from such support. Programs in this collaborative aimed to improve services for people with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Future research should examine whether this approach can be successfully applied to improving services for additional vulnerable populations, such as those with multiple general medical and behavioral health diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

The New York State Office of Mental Health provided funding for the activities described in this report (contract C008324/C008508). The authors thank the programs that partnered with them in the learning collaborative: Catholic Charities Neighborhood Services Inc., CCNS PROS; Federation Employment and Guidance Service, FEGS Brooklyn PROS Possibilities; Federation Employment and Guidance Service, FEGS Bronx PROS Possibilities; Goodwill Industries of Greater New York Inc., Goodwill PROS Rebound; Institute for Community Living Inc., ICL East New York PROS; Mid-Erie Counseling and Treatment Services, Mid-Erie Center for Self-Development (PROS); Pederson-Krag Center Inc., PK PROS North; Postgraduate Center for Mental Health Inc., Postgraduate PROS; Putnam Family and Community Services Inc., PFCS PROSper; The Bridge Inc., Bridge Diane Goldberg PROS; Unity Health System, Unity PROS.