Over a quarter of people with serious mental illnesses become involved with the criminal justice system—an outcome that jeopardizes long-term recovery and substantially increases state costs (

1). The apparent “criminalization of mental illness” has been partly attributed to insufficient access to treatment. Pharmacological interventions have become the cornerstone of treatment (

2), but poor adherence remains a persistent problem for a large proportion of individuals with serious mental illnesses (

2–

4).

Little empirical research has examined the extent to which early and consistent participation in outpatient services and adherence to medications after a psychiatric hospitalization can help people with serious mental illnesses avoid arrest and incarceration, and, if so, what impact this might have on state and local costs. A recent study of criminal justice outcomes in a population of adults in Florida with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder found that monthly medication possession (a proxy for adherence) and receipt of outpatient services significantly reduced the likelihood of arrests (

5). We examined in more detail the impact of the combination of treatment utilization and medication possession on arrest and incarceration outcomes and on costs in Miami-Dade County and Pinellas County in Florida.

Data and procedures

Administrative data were matched and merged from the mental health and criminal justice systems of Miami-Dade County and Pinellas County. A total of 1,367 adults were identified from Florida Department of Children and Families data and Medicaid claims for treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder from July 1, 2002, to March 31, 2008. Matched records from law enforcement and correction systems were used to identify arrests and days incarcerated for these individuals. More details about the methodology are available in the related study of arrest outcomes (

5). All research activities involving the use of private health information for this study were reviewed and approved by the relevant jurisdictional institutional review boards.

Data on use and costs of psychiatric hospitalization, emergency services, routine outpatient services, targeted case management, and psychiatric medication were collected from Florida Medicaid claims. Average cost of an arrest was estimated from a previous study of justice-involved adults with serious mental illness and accounted for police, booking, court, attorney, and transportation costs (

6). Per diem unit costs for incarceration were reported by the two counties: Miami-Dade, $92.98; Pinellas, $79.40.

Medicaid pharmacy records were used to measure an individual’s monthly medication possession ratio (MPR), the proportion of days in the month that the patient had a supply of medications appropriate for his or her diagnosis. This measure is a reliable proxy indicator of adherence (

3,

7,

8). An MPR of ≥80% was considered an indicator of adequate adherence. The number of days during which the person had a high MPR after hospitalization was coded with four categories of dummy variables: 0, 1–30, 31–60, and 61–90 days.

Multivariable time-series regression analysis examined the net effects of monthly MPR and use of outpatient services on risk of arrest and incarceration. Paid Medicaid claims amounts and per diem incarceration costs were attached to outcome data to estimate incarceration costs and treatment cost offsets attributable to adherence and outpatient mental health services use.

Findings

About half the sample was male, and the mean age was 40 years. Twenty-nine percent were white, 23% were African American, and 35% were Hispanic. Most (84%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The average length of the index hospitalization was eight days. Twenty-one percent had a history of arrest.

A regression analysis that controlled for prior arrest, demographic characteristics, diagnosis, and baseline length of hospital stay showed that the number of outpatient service contacts was independently associated with lower risk of subsequent arrest (odds ratio [OR]=.98, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.95–1.00), as was maintaining an MPR of ≥80% in the first 90 days after hospitalization (OR=.80, CI=.65–.99). The mean number of days incarcerated in the subsequent 30 days was significantly higher for those with an MPR <80% (1.36 versus .28 days) and higher for those with no outpatient services in the prior 30 days (1.00 versus .40 days). No significant differences were found in risk of arrest by specific 30-day MPR category. However, a dose-response trend was seen, with greater reduction of incarceration risk for each increment in MPR.

The mean cost of incarceration for a given 30-day period was higher for persons with a low versus a high MPR during the prior 30 days ($123.33 versus $25.31) and for those with no outpatient utilization during the prior 30 days ($92.01 versus $36.58).

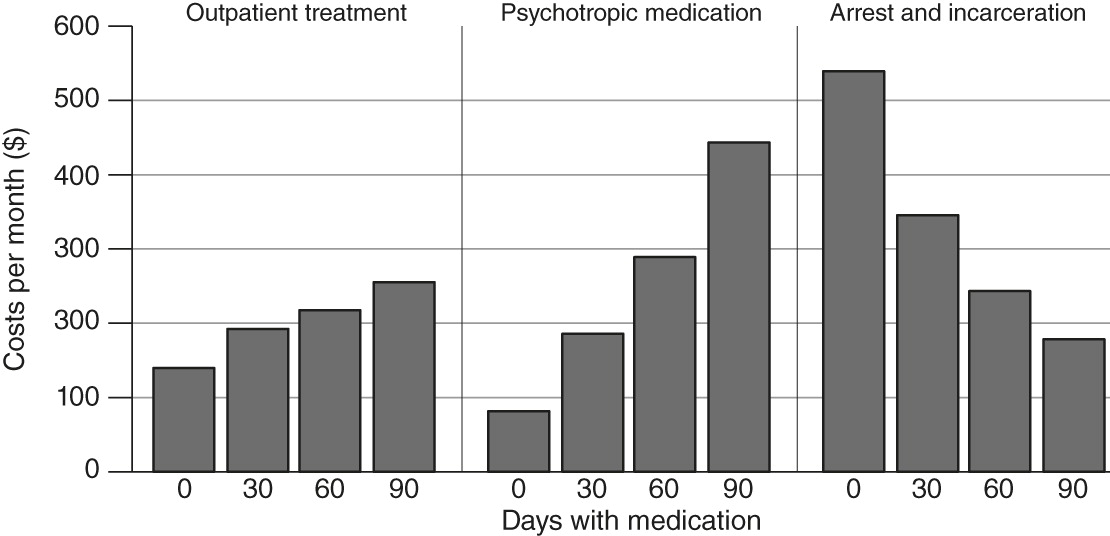

Large variations were noted in average monthly service use and criminal justice costs across types of services, sorted by MPR level in the 90 days posthospitalization. Outpatient treatment and medication costs were higher among patients with higher MPRs, and criminal justice costs were substantially lower (

Figure 1). Inpatient costs were also significantly higher among patients with higher MPRs. Although higher MPRs were strongly associated with reductions in criminal justice costs, those savings were offset by higher treatment costs, resulting in higher total average costs for those with higher MPRs. For example, those with adequate MPRs throughout the 90-day period had mean monthly treatment costs for all service use of $2,199 (inpatient costs accounted for 46%), and their average arrest and incarceration costs were $140. Conversely, those with no days with an adequate MPR in the 90-day period had mean monthly treatment costs of $788 (inpatient costs accounted for 59%), and a mean of $255 in arrest and incarceration costs. Therefore, although overall treatment costs were higher among those with higher MPRs, these individuals used proportionately less inpatient care than their counterparts with low MPRs. [Tables presenting results of analyses described in this section are available in an online

data supplement to this column.]

Implications

Findings suggest that MPR in a critical period of the first 90 days after psychiatric hospitalization, as well as monthly MPR following the first 90 days, were both significantly associated with lower criminal justice involvement and related costs and with higher use of mental health services and related costs. MPR appeared to play an especially influential role: if it was adequate (≥80%), risk of arrest in the subsequent month was low. An inadequate MPR in the first 90 days, as assessed via Medicaid claims data, could serve as an early indicator of increased risk of arrest and incarceration.

Although criminal justice costs were considerably lower among individuals with higher posthospitalization MPRs, average monthly treatment costs were higher—enough so that the net average costs increased as posthospitalization MPR improved. It should be noted that Medicaid treatment costs are shared with the federal government—Florida pays on average about 40% of the cost of Medicaid-reimbursed services—whereas criminal justice costs are entirely borne by the state and counties. Costs for various treatment services increased as the MPR improved, including inpatient care, routine outpatient services, case management, and psychotropic medications. Higher monthly medication costs among those who also had higher MPRs in the first 90 days posthospitalization suggest that their MPRs continued to be superior over time.

The higher relative costs for outpatient services and case management appear to indicate that people with higher MPRs were receiving the treatment they needed—and to a greater extent than their counterparts with low MPRs. Although the proportion of treatment costs attributable to inpatient care was lower for those with higher MPRs, the reasons for their higher absolute inpatient costs are unclear. It is possible that those who had lower MPRs in the first 90 days were more likely to be incarcerated if they were functioning poorly, reducing their availability in the community for subsequent hospitalizations. It is also possible that there were unmeasured factors contributing to individuals’ functioning that influenced their adherence to medication and helped them avoid justice involvement, thereby confounding the relationship between MPR and subsequent arrest and incarceration.

Having a higher MPR in the first 90 days after hospitalization was associated with higher outpatient service use and costs and lower justice involvement and costs. These findings reinforce evidence from other studies that early intervention after hospitalization is especially important for adults with serious mental illness; optimizing treatment continuity during the transition to outpatient care may play a key role in increasing subsequent use of services and reducing recidivism and associated costs (

9,

10). The finding of higher total average costs among those with higher MPRs also highlights the complex budgetary considerations involved in shifting resources for adults with serious mental illness from corrections to community treatment. Improved use of treatment services and reductions in criminal justice costs do not necessarily yield net savings, as was the case in our study, although they may yield savings in other settings. Nonetheless, these results demonstrate that a modest investment in improving treatment participation and medication adherence before hospital discharge, using approaches such as motivational interviewing or other in-reach efforts from community providers, can reduce criminal justice involvement and costs for persons with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was partly funded with support from grant 5316-00 from the Stanley Research Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.