We believe it is necessary to complement the classical approach to shared decision making with other models, interventions, and communication techniques in order to empower mental health professionals and patients and enable them to use shared decision making. We call this integrative approach SDM-PLUS.

Empowering professionals

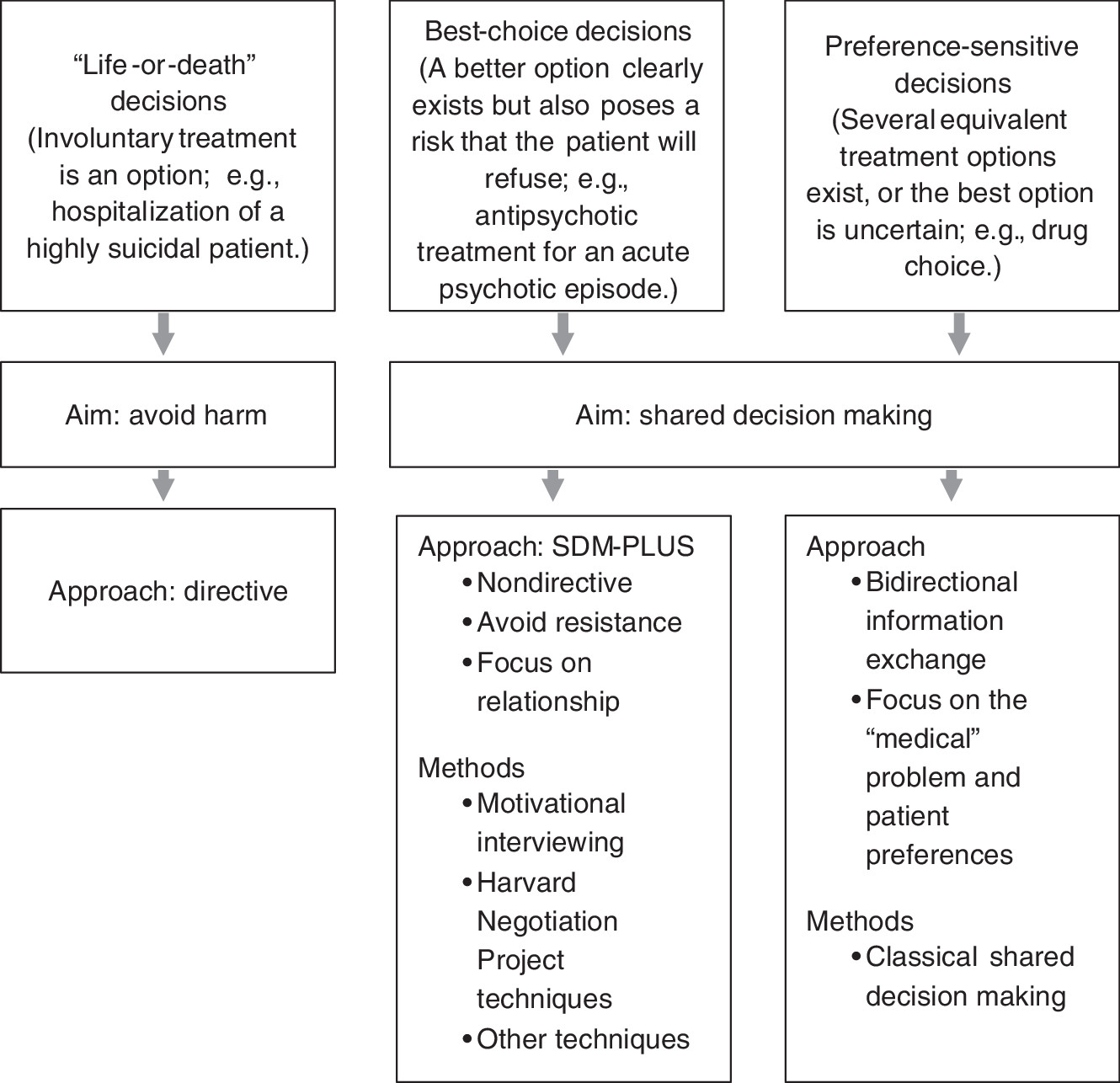

We suggest that mental health professionals need to be empowered to reduce their use of pressure in clinical situations. The first step is to ensure that mental health professionals can analyze clinical situations and classify them into three prototypical decision types that imply different decision-making approaches (

Figure 1). First, there are the very rare “life-or-death” situations in which a wrong decision (for example, discharging a suicidal patient) imposes an immediate threat to the patient or to others. Second, there are preference-sensitive decisions—those with several more or less equivalent options or in which there is uncertainty about the best way to proceed—that constitute most decisions in mental health care. Finally, there are “best choice” decisions, in which professionals agree on the therapeutic approach but anticipate patient resistance. Undoubtedly, life-or-death situations call for a directive approach; however, shared decision making should be used in all other situations.

Further, the individual situation will determine the best approach to shared decision making. For preference-sensitive decisions, the classical approach is advised in mental health settings. This emphasizes describing options, communicating risks and benefits, and identifying patient preferences (

20). More challenging are best-choice decisions because neither the classical approach, which requires some agreement between patient and provider, nor the paternalistic approach, which increases patient resistance, will work if, for example, a patient with poor insight refuses antipsychotic treatment during an acute psychotic episode. In these situations, we suggest use of communication strategies, such as motivational interviewing (

19,

21) and techniques developed by the Harvard Negotiation Project (

22). Motivational interviewing is already used in mental health settings. The Harvard Negotiation Project, developed at Harvard Law School, constitutes a method for negotiating mutually satisfactory agreements. The aim is to reach win-win solutions that go beyond compromising, even in very difficult negotiations (

23). Communication techniques used in motivational interviewing and in the Harvard Negotiation Project overlap—not only with each other but also with shared decision making (

24). Thus it is possible to identify a set of common communication skills that facilitate shared decision making in best-choice decisions. We refer to these skills as SDM-PLUS.

In the situation described above in which a psychotic patient is ambivalent about or refuses medications, a set of these techniques can be used. First, the provider analyzes the situation (rule out life-or-death situation) and concludes that the patient’s participation is the goal. The provider also concludes that classical shared decision making would not be effective as an initial approach because of the patient’s resistance and decides that SDM-PLUS techniques will be more effective, flagging the situation as a best-choice scenario. Second, the provider should actively start the negotiation process with the patient (as suggested by the Harvard Negotiation Project). The negotiation process includes strategies such as taking time-outs, identifying one’s own interests (that is, the option that is seen as the best choice by the psychiatrist), and developing an alternative plan (identifying other potential solutions if the patient does not accept the best-choice option). This step, although it seems self-evident, is one of the crucial elements of successful negotiation and is referred in literature as BATNA (Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement) strategy (

23).

Third, throughout the course of the consultation, strategies adapted from motivational interviewing should be implemented to avoid confrontation, including listening reflectively, evoking change talk, and exploring common ground (

19,

21). In addition, supplementary use of some techniques of classical shared decision making (such as assisting patients to identify or develop their individual preferences) may be helpful in reaching mutual decisions.

Thus we argue that SDM-PLUS techniques are necessary in clinical situations in which there is a lack of agreement between the patient and the mental health provider, because such agreement is the basis for using the classical approach to shared decision making. SDM-PLUS does not replace the principles of shared decision making (

4) but rather serves as a platform to implement shared decision making in clinical situations involving patients with severe mental illness. Practical training in SDM-PLUS techniques is needed for mental health professionals (psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, and psychologists). Because many professionals have some experience with the techniques described above (

24), the training should focus on analyzing clinical situations and applying communication strategies in routine clinical care.

Empowering patients

At all times it is necessary to empower patients in order to facilitate their participation in decision making. Ideally, the goal is to enable patients to demand their preferred level of participation. Existing interventions should be used to create a “participatory atmosphere” that helps to motivate, empower, and enable patients to participate in shared decision making. These interventions include social skills training that addresses communication skills in the context of mental health care to facilitate “self-directed recovery” (

25) and psychoeducation (

26) to increase self-esteem and health literacy. Health literacy can also be improved by use of decision support systems that educate patients to prepare for certain decisions (

27). In addition, some programs specifically address patients’ activation, motivation, and skills to facilitate shared decision making (

28,

29). Finally, implementation of shared decision making can be promoted through incorporation of consumer-driven approaches and peer support that address shared decision making directly (

30) or indirectly by addressing recovery or related fields (

31). To create a participatory atmosphere, we believe that collaboration between the various professions (for example, nurses, psychiatrists, and social workers) is crucial for patient empowerment.