Four recent national studies have reported estimates of prevalence rates of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among children by racial-ethnic group (

1–

4). The rate for white children was found to be higher than for Hispanic children and equal to or higher than the rate for black children. These studies varied in sampling methods, which makes the consistent findings of higher rates for white children all the more striking. The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study followed a nationally representative cohort of U.S. schoolchildren from kindergarten through the eighth grade (

1). Parents reported whether their child had received an ADHD diagnosis from a care provider. The study found that compared with white children, Hispanic children were 44% less likely and African-American children were 64% less likely to have received an ADHD diagnosis by the time they were in eighth grade. The National Survey of Children’s Health, used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to obtain national ADHD prevalence rates, is based on data from a cross-sectional sample of households and on parent reports obtained by telephone for a randomly selected child in the household. The parent is asked whether the child has received a diagnosis of ADHD from any caregiver (

2). In 2011, rates were similar among white (9.8%) and black (9.5%) children, and rates for both were higher than among Hispanic children (5.8%). Data collected in the 2004–2006 National Health Interview Survey from a sample of children ages six to 17, in which “caseness” is also based on parent reports, indicated that rates of ADHD diagnosis among Hispanic children (5.3%) and non-Hispanic black children (8.6%) were lower than among non-Hispanic white children (9.8%) (

3).

Froehlich and colleagues (

4) used 2001–2004 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a general population survey, and reported rates of ADHD among children ages eight to 15 on the basis of direct assessment made by a parent or caregiver with a structured instrument that led to a

DSM-IV diagnosis. The rate among white children (9.8%) was similar to that among black children (8.7%) but higher than that among Mexican-American children (6%). Notably, in the first three cited studies, rates were based on parent report of receipt of a diagnosis from any type of care provider. Froehlich and colleagues’ estimates, which were based on rates among children who may not have been in treatment, are closest to population-based estimates of the true prevalence of ADHD.

In this study, we examined data from children ages three to 17 who were receiving care in the New York State (NYS) public mental health system (PMHS), a system that does not include mental health providers in private practice or primary care physicians who provide mental health services. The study was undertaken to determine whether higher rates of ADHD would be found among white children using the PMHS, in which a smaller set of providers is covered and which notably excludes primary care physicians. We contrast our findings with national findings and propose reasons for observed differences in ADHD rates. We estimated total prevalence rates for use of nonresidential PMHS services and ADHD prevalence rates for whites, blacks, and Hispanics. For these groups, we estimated the proportion of children who received an ADHD diagnosis and compared the odds of blacks and Hispanics versus whites receiving an ADHD diagnosis, controlling for age, gender, and insurance type.

Methods

Data were from the 2011 NYS Office of Mental Health biennial one-week Patient Characteristics Survey (

5) (PCS) of all persons receiving services in a typical week in mental health programs funded, certified, or operated by the NYS Office of Mental Health (that is, all programs in the PMHS). In NYS, the PMHS is comprehensive and covers programs that provide mental health services delivered by any type of psychiatric practitioner, including psychiatrists, social workers, psychologists, case managers, and others; however, the PMHS does not include psychiatric services received in either noncertified or solo practices or delivered by primary care physicians. School-based clinics that provide mental health services are in the PMHS. Note that the word “public” does not refer to the type of insurance, and children with public or private insurance may use PMHS providers. Those with private insurance may use the PMHS by preference or because of a shortage of solo-practice child psychiatric practitioners, which is a particular problem in upstate rural areas.

The study used PCS data collected for children ages three to 17 who were receiving nonresidential emergency, outpatient, or brief crisis services or community supports. Data on clinical diagnosis (DSM-IV-TR), race-ethnicity, age, gender, and type of insurance were included. Diagnosis was dichotomized (ADHD diagnosis and no ADHD diagnosis) and included both primary and secondary diagnoses. Data for three racial-ethnic groups were examined: Hispanic, non-Hispanic white (hereinafter called white), and non-Hispanic black (hereinafter called black). Age groups were three to seven, eight to 12, and 13 to 17. Insurance type was dichotomized (nonprivate and private). Nonprivate included public payers. Respondents who selected “none or other” were included in the nonprivate group. Those with missing data and those who selected “none or other” were included in all counts except the logistic regression described below. For rate calculations, children were grouped into age, gender, and race-ethnicity subgroups. The survey data were deidentified, and because the study was neither clinical research nor a clinical trial, it received exempt status from the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research Institutional Review Board.

Data from the one-week sample are used to estimate the annual number of persons served in nonresidential services, by use of a statistical method (

6) employed by the state since 1988. The accuracy of the method has been tested with data from a NYS county system that collects data over time on all mental health service use. It was shown that the estimate of the annual number was close to the actual number (

7).

The annual prevalence rate of use of PMHS nonresidential services was estimated as the number of persons per 1,000 in the general population who used a PMHS provider for at least one nonresidential service during the year (hereinafter referred to as the total PMHS prevalence rate). This rate is a global measure of access to the PMHS. The annual ADHD prevalence rate among users of PMHS nonresidential services is the number of individuals per 1,000 in the general population who have used a PHMS provider for at least one nonresidential service during the year and who have received a primary or secondary diagnosis of ADHD by a PMHS provider (hereinafter referred to as the ADHD PMHS prevalence rate). The numerators of these two prevalence rates—total PMHS prevalence rate and ADHD PMHS prevalence rate—are the annualized number in treatment and the annualized number with ADHD, respectively. The denominators of both rates reflect the sizes of the racial-ethnic age group in the population, and these data were obtained from the 2010 census (

8). The ADHD PMHS diagnosis rate is the proportion of children who received a diagnosis of ADHD among PMHS users during 2011. The diagnosis was made during or before the sample week. Although some children may have received the diagnosis outside the PMHS, all diagnoses were reconfirmed by PMHS providers. The ADHD PMHS prevalence rate is the product of the total PMHS prevalence rate and the ADHD PMHS diagnosis rate.

The percentages of children with a particular characteristic in the annualized sample were compared among racial-ethnic groups with an asymptotic chi square test that takes into account the unequal variances of the estimators and is performed conditionally on the estimated size of the respective groups (

7). To test equality of prevalence rates, Fieller's theorem was used to form 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for prevalence ratios (

7). If the interval does not cover 1, the null hypothesis of no difference in rates is rejected at the 5% level. We analyzed diagnosis rates by using a logistic regression model to estimate the odds of receiving an ADHD diagnosis, controlling for race-ethnicity, gender, age, and insurance type. The annualized sample used in the regression comprised those who had complete data on all variables in the model (total N=123,358; children with ADHD, N=40,000). The logistic regression model included main effects of the control variables and interaction terms of race-ethnicity with the other control variables. For males and for females within each racial-ethnic group, the odds of having an ADHD diagnosis compared with whites were separately estimated for those with private and nonprivate insurance. Differences were considered statistically significant if a 95% Wald CI did not cover 1.

Results

A total of 32,047 children in the one-week sample received PMHS nonresidential services, which yielded an estimated 133,091 children (CI=129,169–136,913) served in 2011. As shown in

Table 1¸ 38% of the one-week sample had an ADHD diagnosis. As shown in

Table 2, the estimated number of children with ADHD treated in the year was 40,773 (CI=38,947–42,600). Therefore, 31% of the annualized sample of 133,091 children had ADHD diagnoses. In the annualized ADHD sample, 40% were white, 28% were black, and 32% were Hispanic; 75% were males, and 49% were eight to 12 years of age. The percentage of children ages three to seven with an ADHD diagnosis differed among groups; the percentage was lower among whites than among blacks or Hispanics. Among those with ADHD, the percentage with private insurance among whites (32%) was about twice as high as among blacks (16%) and more than three times as high as among Hispanics (9%).

As shown in

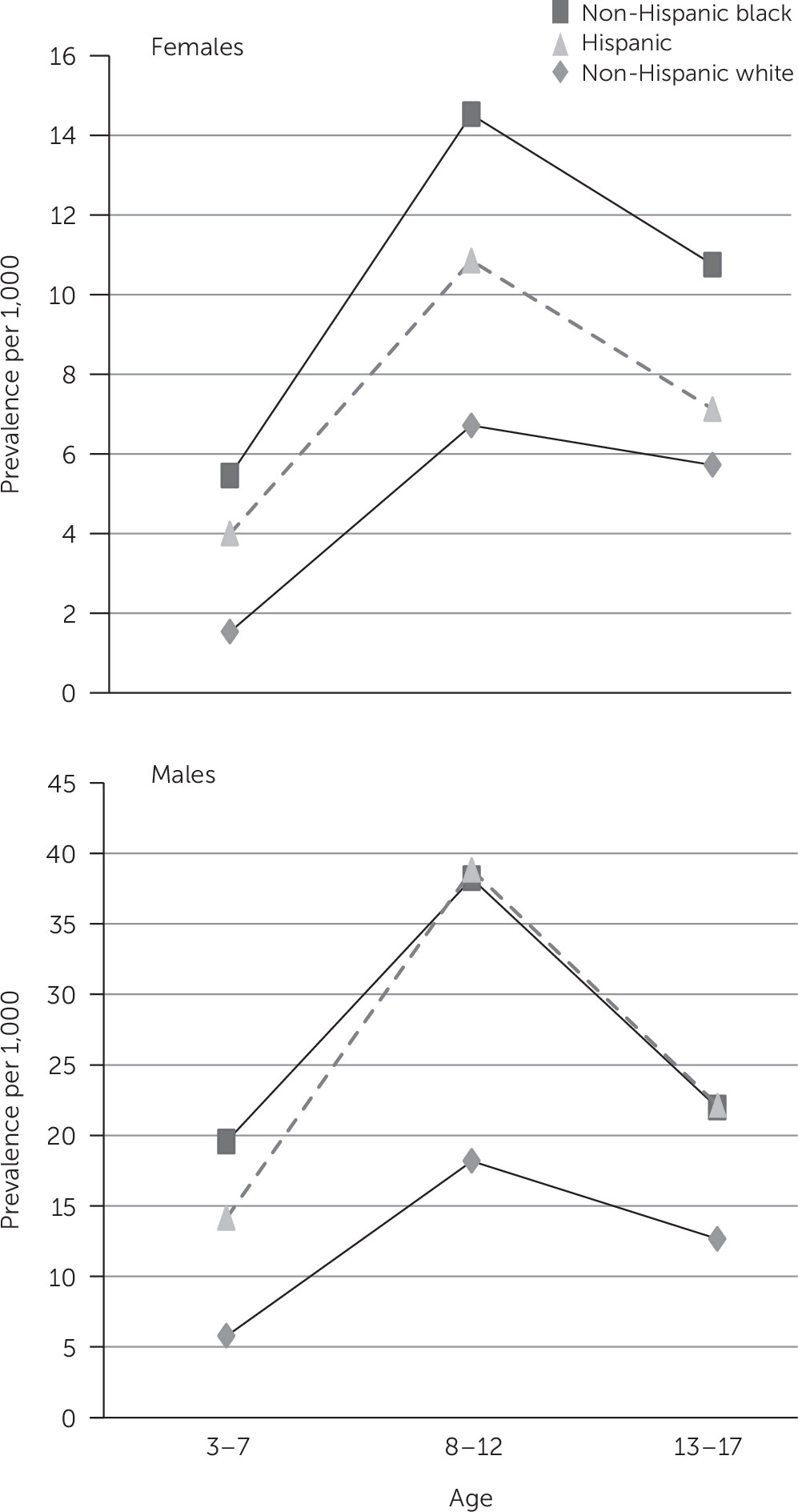

Table 3, the total PMHS annual prevalence rate per 1,000 children ages three to 17 was 40.2, and rates for racial-ethnic groups were as follows: whites, 29.6; blacks, 55.9; and Hispanics, 53.0. The ADHD PMHS annual prevalence rate per 1,000 children ages three to 17 was 12.3, and rates for racial-ethnic groups were as follows: whites, 8.6; blacks, 18.5; and Hispanics, 16.2. Black and Hispanic ADHD prevalence rates were significantly higher than white rates; the rate among females (6.4) was significantly lower than among males (18.0). For each of the gender and age groups, ADHD prevalence rates for blacks and Hispanics were significantly higher than rates for whites, except for females ages 13 to 17, for whom the difference was not significant (

Figure 1). Among age groups, prevalence rates were highest for children ages eight to 12 in all racial-ethnic groups.

The ADHD PMHS diagnosis rate in 2011 for blacks (.33) was significantly higher (p<.05) than for whites (.29), while the rate for Hispanics (.31) did not differ significantly from that for whites. Across all age groups, the diagnosis rate for females (.18) was significantly (p<.05) lower than for males (.39) (

Table 3).

In the logistic regression model, all main effects and interactions were significant (p<.001). Blacks had significantly greater odds than their white counterparts of having an ADHD diagnosis (adjusted ORs [AORs] of approximately 1.2 for females and for males). Both Hispanic females and males had significantly lower odds than their white gender counterparts of having an ADHD diagnosis (female AOR=.71; male AOR=.89). When AORs were examined by type of insurance similar findings were obtained, except for Hispanic males; Hispanic males with private insurance had significantly lower odds than white males of having an ADHD diagnosis, but those with public insurance did not (

Table 4).

Discussion

The prevalence rates of ADHD among white children using PMHS nonresidential services were lower than rates among both black and Hispanic children. This finding is in contrast to higher rates among white children that have been consistently reported in recent studies (

1–

3). The difference in findings may result from the role that insurance plays in access to certain types of providers among various racial-ethnic groups, from cultural differences in care-seeking behaviors, or from diagnostic skills of providers, which may lead to over- and underdiagnosing. [A probability framework developed to motivate these reasons and frame the discussion is included in an

online supplement to this article.]

Because of the type of insurance they carry, white families may be more likely than black or Hispanic families to use private psychiatric practitioners and primary care physicians than to use PMHS providers. For 2011, the prevalence of ADHD among children using PMHS nonresidential services was estimated at 1.2% (12.3 per 1,000 population), whereas the CDC reported that approximately 7.7% of NYS children ages four to 17 had a current diagnosis of attention-deficit disorder or ADHD made by a health care provider, as reported by their parents (

9). On the basis of these statistics, only about 16% of children who had a parent-reported ADHD diagnosis were served by the PMHS. The CDC rates were based on use of a health care system larger than the PMHS, because parents reported receipt of an ADHD diagnosis from any care provider. In 2011, parents whose children used the PMHS were less likely to have private insurance (25%) than persons in the state; statewide 53% of children ages birth to 18 were covered by private insurance (

10). In NYS in 2007, 79% of white children had private health insurance, compared with 35% of Hispanic children and 50% of black children (

11). Persons in the general population who have either public insurance or no insurance might be more likely to use the PMHS, whereas those with private insurance might be more likely to seek services from private psychiatric practitioners not in the PMHS or from general practitioners. Notably, office visits to treat ADHD were reported to have grown by 66% between 2000 and 2010, which was mainly accounted for by families seeking help from pediatricians (

12).

Differences in help-seeking behaviors may also explain why white families make greater use than black and Hispanic families of private psychiatrists and other providers in the private health sector for their children’s ADHD symptoms. Culture shapes parental expectations of children’s behaviors both at home and in school. Cohen and colleagues (

13) reported that African-American parents may not respond to their children’s ADHD symptoms in a fashion similar to Caucasian parents and may not respond as early after the appearance of these symptoms. Similarly, Bussing and colleagues (

14) noted that although black parents may find a hyperactive child difficult to manage, they may not view hyperactivity as a medical problem, which would reduce their motivation to mention it to a primary care provider. Even if black parents are troubled by such behaviors, an aversion to the use of psychiatric medications (especially for their children) may impede early care seeking (

15). However, teachers are not likely to miss the symptoms of hyperactivity (

16), and they may refer black children to known programs or clinics in the PMHS rather than to private psychiatrists or pediatricians. Hispanic mothers, particularly those who are less acculturated to U.S. systems, and teachers may not seek help for inattention and daydreaming (

17) among teenage Hispanic girls, because these symptoms may not be viewed as problematic to their participation in quiet activities and in household-related activities (

18).

In addition, non-PMHS clinicians may diagnose differently from those in the PMHS. Psychiatric clinicians in private practice and in the PMHS have received similar training and are thus not likely to differ. However, primary care physicians may not be adequately trained to make psychiatric diagnoses, which may lead to under- or overdiagnosing of ADHD among children. Health practitioners may not use structured assessment tools or may not elicit sufficient information, particularly culturally nuanced information, to make a valid ADHD diagnosis. We are unaware of any studies comparing ADHD diagnoses made by psychiatric practitioners to those made by primary care physicians, most particularly with respect to differences in diagnosing patients from racial-ethnic groups.

There are limitations to the interpretation of findings. NYS data may be idiosyncratic and not generalizable to the national picture. However, this is highly unlikely because most national data (for example, on insurance and ADHD rates) are aligned with NYS data. In addition, data for NYS reported by the CDC are in line with national rates. Possible cultural explanations for our findings are derived from a literature that is anecdotal and speculative and often based on small qualitative studies. Diagnoses in this study were assigned by providers, and we cannot comment on the extent to which any diagnostic guidelines were followed or whether input was obtained from both parents and teachers. Clinically based diagnoses, however, are unarguably more reliable than those based solely on parent self-reports, which were used in three of the studies described above (

1–

3). Clinically based diagnoses are also more germane to the comparison of PMHS rates than are parent or caregiver reports of diagnoses. Our speculation that private insurance played a role in driving access to providers outside the PMHS is limited by lack of data or prior research. Answers to the following questions would help substantiate some of our speculations: Do children from racial-ethnic minority groups who have private insurance differ between sectors? Are parents with private insurance more apt to choose providers outside the PMHS? Do children who use the PMHS have more comorbidities than those who do not use the PMHS? These questions outline an agenda for future research. Finally, we cannot rule out explanations proposed by other authors for variations in rates of ADHD, such as differential environmental risk exposures (

19), genetics (

20), and health complications (

4).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the higher ADHD prevalence rates among white children that have been reported in national studies are likely attributable to greater use of primary care physicians by white families, between-group differences in care-seeking behaviors, and higher rates of private insurance among white families. Revisiting the findings of this study when the insurance coverage scene under the Affordable Care Act has settled down may further clarify the impact of insurance on ADHD prevalence rates. To determine whether differences in diagnostic practices between PMHS and non-PMHS clinicians are sufficient to result in our findings of lower ADHD prevalence among white children—in contrast to previous studies—will require studies of ADHD diagnostic concordance, particularly with regard to differences between psychiatric clinicians and primary care clinicians. In addition, the somewhat higher PMHS ADHD diagnosis rate in 2011 for blacks and the lower diagnostic rate for Hispanics, especially for females, suggest the possibility of misdiagnosis by PMHS clinicians that might be based on misunderstanding of cultural differences. Children from racial-ethnic minority groups who seek care from any provider would likely benefit from more nuanced culturally based diagnostic assessments.