Experiences of stigma are common among persons with schizophrenia, which has been shown in varied geographic and cultural settings (

1). Relatives of and others with close social connections to a person with schizophrenia may also experience stigma. This phenomenon, first described in the 1960s (

2), is known by several terms, including “courtesy stigma,” “stigma by association,” and “associated stigma.” Associated stigma was reported by 16% of relatives in a U.S. study (

3). The corresponding percentage in a study in Morocco was 41% (

4). Family members sometimes avoid situations that might elicit stigma. This form of stigma, known as “anticipated stigma,” was reported by half of the family members in a U.S. study (

5).

Qualitative studies capture the depth and breadth of family experiences of stigma (

6–

9). The impact of stigma has been quantified in several family studies. Among Swedish family members, 83% reported that stigma affected at least one psychological domain; proportions of the sample endorsing individual stigma items ranged from 6% to 40% (

10). In a U.S. study, family members’ endorsement of items related to stigma impact ranged from 8% to 22% (

11). To aid the quantification of the scope and impact of relatives’ experiences, Canadian researchers developed the family version of the Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences (ISE) (

12). In a field test of the ISE family version, 20% of participants often or always felt stigmatized because of the relative’s mental illness, and half stated that experiences of stigma affected the family’s quality of life.

Being part of a well-functioning family is important for recovery in schizophrenia (

13), and stigma may contribute to the family’s overall burden. In a study in China, 28% of the participants reported moderate to severe impact of stigma on family life (

14). In a Hong Kong study, stigma was shown to lead to social isolation, resulting in lack of support, which generated increased family burden (

15). In a U.S. study that focused on Latino caregivers, 40% were at risk of depression, which was related to perceived stigma (

16). Both experienced stigma and anticipated stigma generated feelings of burden among relatives of individuals with first-episode schizophrenia in a study in Australia (

6). Findings from studies that focus on families of patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis cannot be directly extrapolated to families of persons with long-term illness, because there is evidence that burden may change over time (

17). Further, the amount of burden reported by a family member varies across cultures and may be influenced by the availability of mental health services (

18).

The aim of this study was to use the structured ISE questionnaire to explore stigma experiences of relatives of persons with schizophrenia in a treatment setting in which outpatient practices include components of assertive community treatment (ACT) (

19,

20). A second aim was to examine the relationship between relatives’ stigma experiences and overall burden as measured by the Burden Inventory for Relatives of Persons with Psychotic Disturbances (BIRP) (

21).

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the larger COAST study (Cognition, Adherence, and Stigma in Schizophrenia), which was conducted to examine adherence to oral antipsychotics (

22) and experiences of stigma (

23) among outpatients in the Gothenburg, Sweden, area. Inclusion criteria were age 18–65, prescription of unsupervised oral antipsychotics, and a

DSM-IV clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like psychosis. Exclusion criteria were treatment with long-acting injectable medications, past-year inpatient care for substance use, acute suicide risk, severe intellectual impairment requiring special education, and the need for an interpreter. At the start of the study, patients (N=131) were asked to identify a family member or close friend who might be willing to respond to a mailed questionnaire. Eighty-five percent of the patients (N=111) provided names and addresses. Questionnaires were returned by 75 persons (68%). Three of these were excluded because the respondent was the patient’s professional caregiver, and another seven were excluded because of incomplete information, leaving a final sample of 65.

Procedure

Data were collected during 2008–2010. After approval by the patient, information about this study, along with consent forms and study questionnaires, was sent to the 65 relatives. Questionnaires were self-administered. Relatives who did not respond were mailed up to two reminders. All participating patients and their relatives provided written consent. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Gothenburg.

Instruments

Family version of the ISE.

The family version of the ISE was used to measure stigma. The version employed in this study showed good reliability in a population of relatives of persons with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses (

12). The ISE includes 15 sociodemographic items, followed by the Stigma Experience Scale (items 16–32) and the Stigma Impact Scale (items 33 a–d and 34 a–c). The Stigma Experience Scale measures the frequency of personal experiences of stigma, both actual and anticipated stigma, along with thoughts about public views of mental illness and coping strategies. Responses for items 16–20 are ascertained with a 5-point Likert scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always), and items 25–27 and 29–32 have categorical responses (yes, no, and unsure). High internal consistency (Kuder-Richardson coefficient of reliability=.76) was reported by the developers of the scale (

12). The scale also includes five items with qualitative free-text answers, but these were not analyzed in the study reported here.

For this study, responses on the Stigma Experience Scale were recoded into binary variables, where 1 reflected high expectation of stigma (sometimes, often, always, or yes) and 0 reflected low expectation (never, rarely, or no). The Stigma Impact Scale quantifies the impact of stigma on quality of life, social contexts, family relations, and self-esteem. Items 33 a–d focus on personal impact and items 34 a–c on familial impact. Responses on the Stigma Impact Scale are rated from 0 to 10, where 0 is the lowest possible impact and 10 is the highest possible negative impact. A high reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α=.93) was reported for the Stigma Impact Scale (

12).

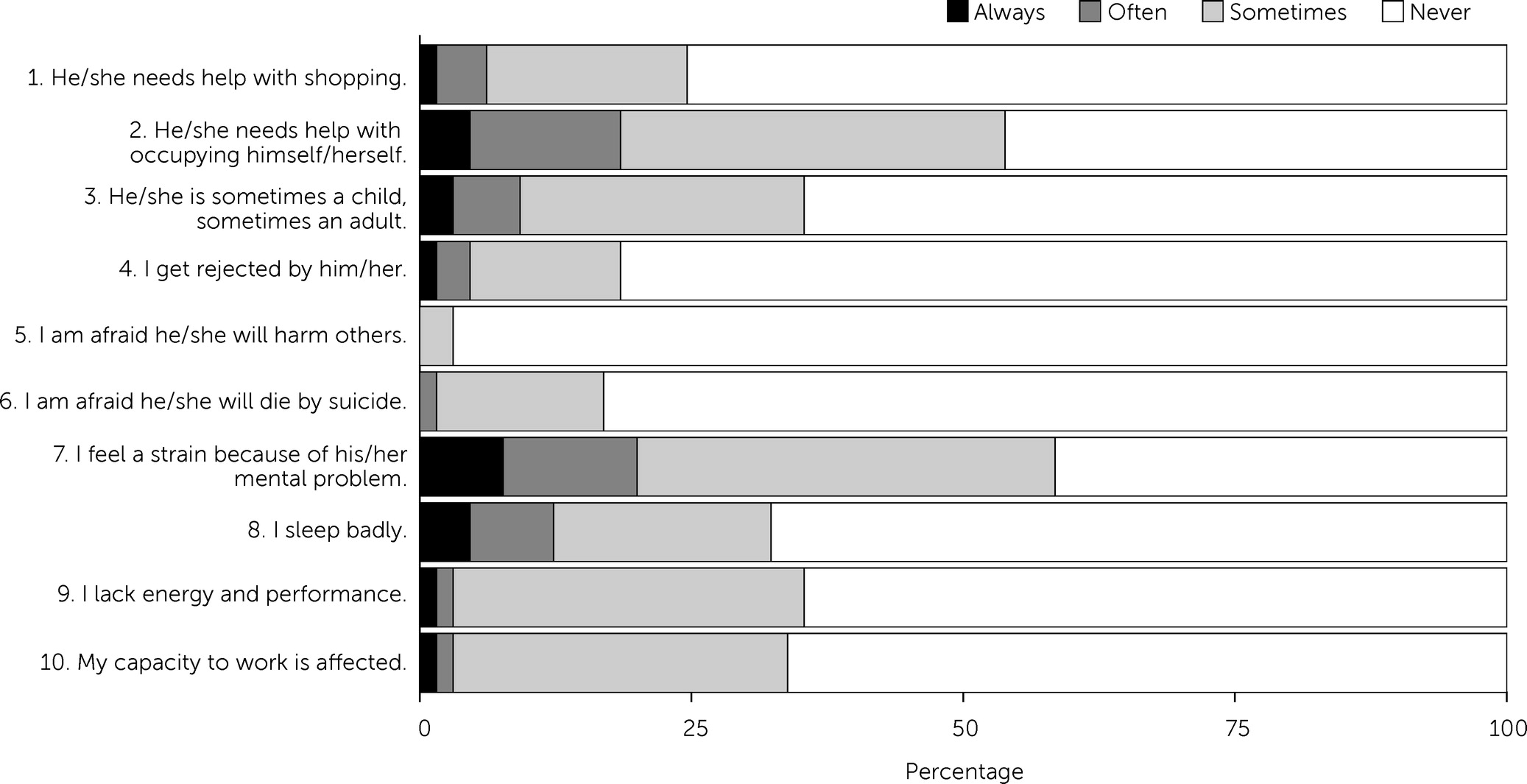

BIRP.

Relatives’ perceived burden was rated with the BIRP. The instrument consists of ten items; items 1 and 2 focus on practical burden, items 3–6 examine emotional burden, and items 7–10 concern the relative’s own health. Each item has four response alternatives (1, no; 2, sometimes; 3, often; and 4, always). Scores are summed to yield a total score (10–40 points); a higher score reflects a higher burden. Regarding internal consistency, the developers of the BIRP reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .73 (

21).

Ratings of symptom burden and function.

Patients’ symptom severity was rated by the research psychiatrist with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Psychosocial functioning was rated in accordance with the function scale of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF).

Statistical Analysis

Group comparisons were carried out with the Student’s t test for continuous variables. For categorical variables, differences in proportions were tested with the chi square test. To analyze the relationship between associated stigma and overall burden for relatives, we wanted to concentrate specifically on an item that captured the relative’s own experience of stigma. Item 19 (“Have you felt stigmatized because of your relative’s mental illness?”) was deemed to be the item that best captured this phenomenon, and those who responded sometimes, often, or always were considered to have experienced stigma. To analyze the relationship between anticipated stigma and overall burden, item 29 (“Do you try to avoid situations that might be stigmatizing to your family?”) was considered to be the most appropriate, and those who responded sometimes, often, or always were considered to have responded affirmatively. Because frequency but not severity is quantified for both these items, we also wanted to include measures of impact. To this end, items 33 a–d were used to analyze the relationship between stigma impact and overall burden on the individual level, and items 34 a–c were used to explore potential associations on the family level.

Associations between the above-specified ISE items and BIRP total score tertiles (here referred to as mild, moderate, and severe) were analyzed with ordinal logistic regression. This is an extension of binary logistic regression that can handle ordinal outcomes—that is, variables with categories that can be ranked in some order. The resulting odds ratios for the covariates are interpreted as the effect of a 1-unit increase in a given covariate on the odds of reporting a higher category of stigma or burden (

24). For example, in our study a 1-unit increase in a given ISE variable led to a corresponding increase in the odds of being in the severe burden category, compared with the mild and moderate burden category—or an increase in the odds of being in the moderate and severe category, compared with the mild burden category. The assumption that odds ratios are proportional across these comparisons, the proportional odds assumption, was tested in all models. In a first step, we analyzed the individual ISE variables listed above in univariate ordinal logistic regression models. In a second step, we analyzed them in separate ordinal logistic regression models, adjusting for confounders. We screened the potential confounders gender, age, symptom burden (PANSS total), and patient functioning (GAF) separately in univariate ordinal logistic regression models, and variables with p values lower than .25 were entered as confounders. SAS 9.3 and IBM SPSS 21.0 were used for all analyses.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to employ structured instruments to examine the relationship between experiences of both stigma and burden among relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Although over half reported that their ill relative had been stigmatized (sometimes, often, or always), only 18% reported that they themselves had felt stigmatized. In adjusted models, the impact of stigma on the ill relative and on the family was associated with higher overall burden.

The frequency of stigma experiences was relatively low in this study compared with a previous study that tested the family version of the ISE (

12). In that study, the target population included parents who attended family-oriented advocacy groups, family network meetings, or family conferences. These individuals may have been more likely to acknowledge stigma than relatives recruited via patients attending an outpatient clinic, as in our study. Another explanation may be that less than one-tenth of the relatives in our study lived with their ill relative, a proportion considerably smaller than in the other study (50%) (

12). This difference is important, because relatives who do not live with their ill family member are less likely to be affected by stigma (

10). The need to avoid potentially stigmatizing situations would not arise as often in these families, which may explain the relatively low rate of anticipated stigma in our study. No patients in our study were receiving long-acting injectable medications, which are typically given to those with greater psychopathology. Therefore, our results may not generalize to all families of persons with severe mental illness (

25). The mean duration of illness among patients in our study was long, almost two decades, which would be expected to influence relatives’ experiences of stigma. However, it was not feasible to test for interactions with patient age or illness duration because of the limited sample size.

Relatives’ own views about stigma may influence their behaviors and interpretations of the questions in an instrument such as the ISE. In recent years, antistigma efforts have been launched in Sweden and elsewhere (

26). The large proportion of relatives who believed that the general public looks down on persons with mental illness—93% in our study compared with 43% in a previous study (

5)—might be partly related to the fact that stigma issues are now recognized to a greater extent than in the past. A quarter of the relatives stated that stigma experiences motivated family members to speak out for the rights of persons with mental illness, which suggests not only awareness of stigma as a societal issue but also a conviction that stigma is something that can be spoken about openly.

The mean BIRP score (14.2) in our study was similar to that reported for the “moderate burden” group of relatives of persons with psychosis (14.8) in a study conducted by the developers of the scale (

27). In our study, burden was related to the impact of stigma on a variety of psychosocial factors, including family relations, social contacts, and self-esteem. The mechanisms of these associations could not be clarified with this study design. The lack of association between experienced stigma and burden was unexpected and might be partly related to the fact that the ISE item measures frequency but not intensity. There is also an issue related to statistical power; data for relatives were available for only half of the patients who took part in the original study, either because of patients’ unwillingness to identify relatives who might be able to participate or relatives’ refusal to participate. Among relatives in our study, the number acknowledging that they themselves had experienced stigma was lower than anticipated, which further reduced the possibility of detecting significant associations. In addition, many patients in our study participated in case management programs, and their relatives were involved in psychoeducation and stress management interventions (

28). Case management and ACT have been shown to have positive effects on relatives in terms of burden and satisfaction with care (

29,

30).

Several methodological issues need to be considered. The sample in the validation study of the ISE family version (

12) included persons with various diagnoses; not all persons had psychotic disorders. The BIRP was developed and validated specifically for relatives of persons with psychotic disorders. Although it can be argued that instruments based on recall underestimate relatives’ objective burden (

31), an alternative method, such as continuous report by diary, might not be as suited to the quantification of mental strain and other phenomena captured by the BIRP.

Patients whose relatives did not participate in our study had higher PANSS scores. Therefore, the ISE and BIRP scores in our study may not reflect stigma and burden among all relatives of patients with psychotic illness. Symptom severity may affect relatives’ stigma (

3) and burden (

27,

32). In addition, relatives of patients with lower education levels were underrepresented, although it is unclear how this might have affected our results.

Our data were limited to a single relative or close friend who we assumed to be a “key” person. Family members who are not key relatives also can experience significant burden (

33), and we can draw no conclusions about them. The limited sample size meant that we could not explore potential gender differences in the association between stigma and burden. Further study is warranted because female and male relatives perceive burden differently (

34).