People with serious mental illness not only are affected by the health consequences of their illness but also may be victims of stigmatizing attitudes held by the general public, which can diminish self-esteem, influence psychosocial functioning, and discourage help seeking (

1–

6). Studies have indicated that providers share many of these stigmatizing attitudes with the general public. Some studies have found that provider attitudes are more negative than those of the general public (

7–

17). Although the consequences of stigmatizing attitudes and expectations among health care providers have not been extensively investigated, recent evidence suggests that providers with more stigmatizing attitudes are less likely to refer individuals with serious mental illness for specialty care or to refill their prescriptions (

18). Stigmatizing provider attitudes could have multiple other consequences, such as discouraging a patient’s recovery, vocational advancement, or help seeking (

5).

Among the general public, interventions involving direct contact with a person with serious mental illness have been shown to be effective in reducing stigmatizing attitudes; contact with persons with mental illness has been shown to be inversely associated with discrimination toward people with serious mental illness (

19,

20). However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated whether contact with persons with mental illness influences health care provider attitudes. Although providers, like the general public, may have personal contact with persons with mental illness among their family members and friends (which we refer to as personal contact), they differ from the general public in that they also have contact with persons with serious mental illness in their training and clinical practice (professional contact). In addition, the professional contact is likely to include persons with mental illness who are very ill, including contact with symptomatic individuals. Although contact with individuals with serious mental illness who are not symptomatic and are functioning well could positively influence attitudes of the general public and health care providers toward persons with mental illness (

19,

21), familiarity with highly symptomatic persons could negatively influence attitudes (

22).

In this study, we examined the relationships between provider contact (personal or professional) with persons with mental illness and provider stigmatizing attitudes and clinical expectations toward persons with mental illness. We hypothesized that provider contact (both professional and personal) with persons with mental illness would be associated with clinical expectations and that this relationship would be mediated by provider stigmatizing attitudes.

Methods

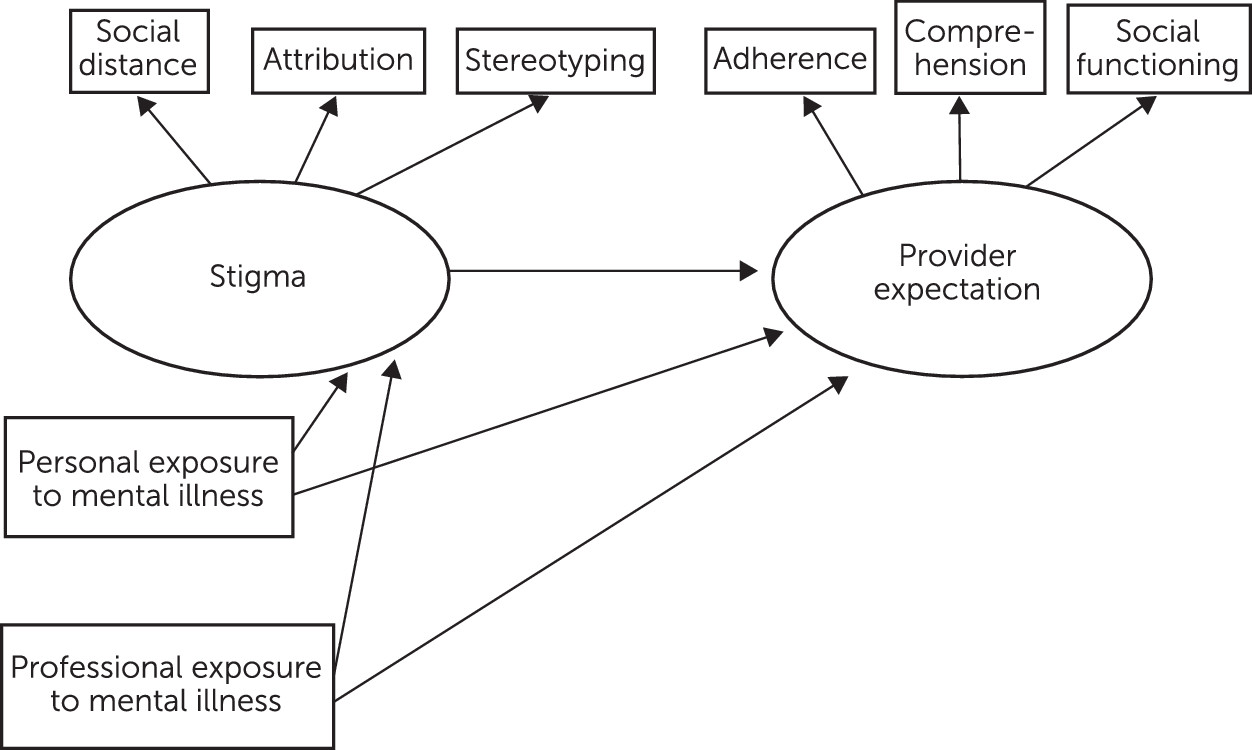

The hypothetical relationship between provider contact and stigma and between provider stigma and expectations is summarized in

Figure 1. We operationalized provider stigma by using standard measures social distance, attribution, and stereotyping. Clinical expectations were measured by responses of providers to questions about their perception of a vignette patient’s ability to adhere to treatment, read and understand printed health education materials, and engage in social or vocational activities.

The data for these analyses were collected as part of a larger study examining provider attitudes and clinical expectations in regard to a vignette of a patient with schizophrenia who is seeking treatment for back pain (

16,

23). Between August 2011 and April 2012, we surveyed 351 health care providers (67 mental health nurses, 62 psychiatrists, 76 psychologists, 91 primary care nurses, and 55 physicians) employed by five Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers in the southeast and south central areas of the United States. Each participant completed a survey that included a vignette describing a patient, followed by a series of demographic and attitudinal measures. The surveys were identical, except that one vignette included the diagnosis of schizophrenia in the description of the patient, whereas the other did not. For the study reported here, only surveys that used the vignette that included a patient with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were analyzed (N=192). This vignette was intended to depict a person with schizophrenia who had been functioning well, socially and vocationally, for several years. [The vignette is presented in an

online supplement to this article.]

The study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board. Details of recruitment have been described elsewhere (

16).

The majority of our provider sample was female (N=120, 63%). Participating providers were Caucasian (N=110, 57%), African American (N=29, 15%), Asian or Asian American (N=24, 13%), Hispanic (N=13, 7%), American Indian/Alaska Native (N=2, 1%), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (N=1, <1%). Almost 4% (N=7) reported other race, and 3% (N=6) had missing race-ethnicity data. Thirty-six percent (N=70) of the respondents were primary care nurses or physicians, and 64% (N=122) were mental health nurses, psychiatrists, or psychologists. On average, participants reported 16.5±12.1 years of clinical experience, and 88% (N=169) were currently working full-time at the VA. Data on age were collected as follows: 7% (N=13) of the sample were less than 30 years old, 32% (N=61) were 31 to 40, 22% (N=43) were 41 to 50, 28% (N=54) were 51 to 60, and 11% (N=21) were over age 60.

Measures

Provider contact with mental illness was operationalized in two categories: personal contact and professional contact. Personal contact was assessed with the following three questions (yes, no, or prefer not to answer for each): “Have you ever received professional help for mental health problems?” “Have any of your family members or close friends ever been treated for a mental health problem or mental illness?” “Do you have any family members or close friends who have schizophrenia?” A “yes” response to any question was considered to be evidence of personal contact. We collapsed responses because they all pertain to closeness and familiarity with mental illness of close family or friends, in addition to a personal history of mental illness. Professional contact with patients with mental illness was assessed with only one question: “Approximately what percentage of your current patients have any type of mental illness?”

Provider mental illness stigma was assessed as a latent variable that was operationalized by measures of social distance, attribution, and stereotyping (

Table 1). We measured stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs with the Stereotyping Scale (

24), the Attribution Questionnaire (AQ-9) (

25), and a Social Distance Scale (

26).

Provider stereotyping was measured by using the Stereotyping Scale (also called the Characteristic Scale) (

24). Respondents rate the qualities of the hypothetical patient on a 7-point scale of quality pairs, such as “safe-dangerous” (

Table 1). Higher scores denote greater provider stigma. For this study, ratings on the nine items were summed to create an overall scale representing the “Stereotyping Scale” on the basis of explanatory and confirmatory factor analysis (α=.83).

We used eight of the original nine items on the AQ-9 (

25) to assess affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to the study vignette on a 9-point response scale (1, not at all; 9, very much). The ninth question was dropped because it was not applicable to our study. We conducted an exploratory factor analysis on these questions and identified six items as defining a single factor. Further confirmatory analysis verified the adequate fit of this factor (

Table 1). Ratings on these six items were then summed to create an overall scale (α=.76), with higher scores denoting more negative attribution.

We measured desire for social distance with five items from the General Social Survey (

26). Each of these items had a 4-point response option, and the responses were summed to create the Social Distance Scale on the basis of the explanatory and confirmatory factor analysis (α=.86) (

Table 1). A higher score on this scale denotes greater desire for social distance and, therefore, a more negative attitude.

Provider expectations were operationalized by using three sets of questions that assessed provider expectations of the vignette patient’s adherence to treatment, ability to read or understand health education materials, and social and vocational functioning. For each category of provider expectations, items were summed to create an overall summary measure representing the specific factor on the basis of explanatory and confirmatory factor analysis (α=.71–.89). Adherence to treatment (three items, α=.89) was assessed with questions about the likelihood that the patient would adhere to medications, keep regular appointments, and refill medications in a timely manner. Ability to read or understand educational materials (four items, α=.88) included questions about the likelihood that the patient would read educational material provided about hypertension, understand the material about hypertension, read educational material provided about nutrition and diet, and understand the material about nutrition and diet. Expectations of social and vocational functioning (three items, α=.71) included questions about the likelihood that the patient would advance in his job, get together socially with friends or neighbors on a regular basis, and be able to live on his own (

Table 2).

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM), a methodology that incorporates confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and regression analysis, was used to test the hypothesized model in

Figure 1. Prior to testing the hypothesized structural model, we followed Anderson and Gerbing’s (

27) two-step approach for testing SEMs. The first step is to perform a CFA to assess the relationships among our two latent constructs of provider stigma and provider expectations. This step is referred to as the measurement model, where the two latent constructs are allowed to freely correlate. After constructing a measurement model with adequate fit, we evaluated the hypothesized structural relationships among variables described in

Figure 1. For both the measurement and structural models, we used three indices that assessed model fit: values greater than .90 for Bentler’s comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and values less than .07 for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (

28,

29). In addition, we examined the model chi square goodness-of-fit statistic; however, it was not used as the primary model assessment given some of its unsatisfactory properties, such as sensitivity to sample size (

30,

31).

Most variables in our data had missing values, ranging from 2% to 13%. To minimize potential bias arising from missing data, multiple imputations were conducted with the SAS MI procedure (

32). We used the Mplus statistical package, version 6.1 (

33) to perform and combine the results from both the measurement and structural models based on the imputed data set.

Results

A two-factor model was tested with CFA without prespecifying relationships between provider stigma and expectations. This measurement model provided an adequate fit with model assessment indices (CFI=.96, TLI=.93, and RMSEA=.07). The chi square goodness-of-fit statistic was statistically significant (χ2=17.5, df=8, p=.025). All standardized factor loadings were statistically significant for both provider stigma (values ranged from .53 to .82, p<.001) and provider expectations (values ranged from .57 to .73, p<.001). Therefore, both latent constructs appear to have reliable indictors.

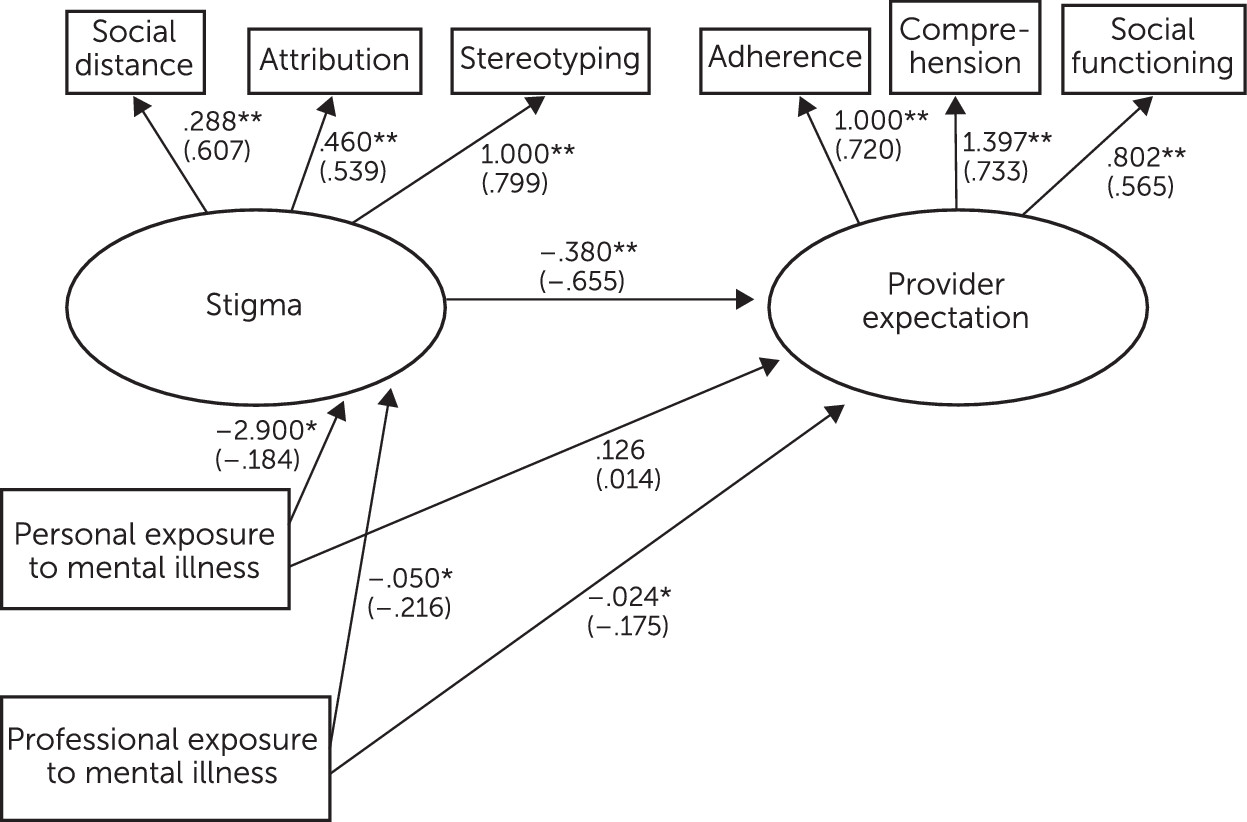

Next, we tested the hypothesized model shown in

Figure 1. The chi square test for model fit was not statistically significant (χ

2=26.2, df=16, p=.051). The fit indices all suggested a satisfactorily fit model (CFI=.96, TLI=.93, and RMSEA=.06). Both the unstandardized and standardized loading estimates for each latent construct are presented in

Figure 2, and the effects decomposition among contact, stigma, and provider expectations are given in

Table 3.

As expected, the final loading coefficients for both latent constructs were consistent with the results from the CFA. More specifically, both constructs appear to have reliable indictors, with a composite reliability of .69 for provider stigma and .71 for provider expectations. The results of the final model (

Table 3 and

Figure 2) indicate that the indirect effect of professional contact on provider expectations was statistically significant, with a standardized estimate of .142 (p<.05). Specifically, providers with higher professional contact with mental illness had lower stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs and, in turn, had higher expectations of the patient with schizophrenia. In addition, the direct relationship between professional contact and provider expectations was statistically significant, with a standardized estimate of –.175 (p=.040). This indicates that without mediation by provider stigmatizing attitudes, professional contact was associated with lower provider expectations.

As with professional contact, the compound path constituting the specific indirect path from provider personal contact with mental illness to provider stigma and on to provider expectations was statistically significant, with a standardized estimate of .121 (p<.05). This result indicates that providers with higher personal contact with mental illness had lower stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs and higher expectations of the patient with schizophrenia. The direct relationship between provider personal contact with mental illness and provider expectations was not statistically significant (p=.87), indicating that provider personal contact with mental illness did not directly influence provider expectations of the patient with schizophrenia.

Discussion

Our findings support the hypothesis that greater provider personal and professional contact with persons with mental illness would be associated with less stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with schizophrenia, which in turn would be associated with higher provider expectations of patient treatment adherence, ability to read and understand health education materials, and social and vocational functioning. These findings should be viewed as preliminary in a field of research that is under development. Research with the general public has shown that familiarity with individuals with mental illness (including exposure via movies, television, associations at work, a family member or friend with mental illness, and a personal history of mental illness) is inversely associated with stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with mental illness (

19,

20,

34). The results of our study extend these findings to stigmatizing attitudes of health care providers but also show that provider attitudes, in turn, influenced clinical expectations. We recently reported a path analysis that described a similar relationship between mental health stigma among providers and their health care decision making. This study reported that primary care providers who endorsed stigmatizing characteristics of a patient were more likely to believe the patient would not adhere to treatment and, therefore, were less likely to refer the patient to a specialist or write a refill prescription (

18). Together, these two studies are the first to demonstrate a relationship between provider stigma and provider clinical expectations. On the basis of these preliminary findings, it is possible that these expectations influence how providers make clinical decisions. For example, if a provider is concerned about poor treatment adherence, he or she may be less likely to refer the patient for hepatitis C treatment.

An interesting finding of our analysis is the contrast between the associations of personal and professional contact. Although both professional and personal contacts exerted an indirect influence on provider expectations through effects on stigmatizing attitudes, only professional contact had a significant direct association with provider expectations.

Recent empirical studies involving health care providers have suggested that the relationship between provider contact and provider stigma may not be linear. One potentially important characteristic of contact, not measured in our study, relates to exposure to different types of patients. For example, routine contact with more symptomatic patients might have different effects than routine contact with high-functioning patients. Indeed, findings from Mårtensson and colleagues (

21) and Hansson and colleagues (

22) seem to support this idea. Findings from these studies suggest that providers working in ambulatory settings, where they were in contact with less symptomatic, more high-functioning individuals with mental illness, had more positive views than providers working in mental health residential settings. This implies that providers working with sicker patients with mental illness may be in greater need of stigma reduction interventions.

Provider stigma has been implicated as a possible contributor to health care disparities for persons with serious mental illness. The findings of this study suggest that interventions that increase provider familiarity with persons with serious mental illness may decrease stigmatizing attitudes and promote affirmative behaviors to potentially decrease disparities in general medical care.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. The study utilized a hypothetical clinical vignette, and provider responses to the vignette may not reflect what they would do in actual practice. Also, the study used a cross-sectional design, and, therefore, we could not determine causality. In addition, all providers in the study were employed at the VA, and thus they cannot be considered representative of providers in general. As such, these findings will need to be replicated in other health care systems.

Conclusions

The findings of this study help to elucidate the relationship between health care providers' personal and professional contact with individuals with mental illness and provider stigma and clinical expectation. Health care providers who reported greater contact with persons with mental illness endorsed fewer stigmatizing attitudes and were more likely to have positive clinical expectations. These findings may be relevant for developing stigma reduction programs for providers.

Studies that focus on developing interventions involving efficacious contact to promote affirming behaviors by providers toward persons with serious mental illness are warranted. Future studies incorporating prospective designs would provide a clearer understanding of how personal and professional contact with persons with mental illness, as well as the type of contact (with highly symptomatic or with high-functioning patients), are related to provider stigmatizing attitudes and clinical expectations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Marder, M.D., Richard Owen, M.D., Lisa Dixon, M.D., and Alex Young, M.D., M.S.P.H., who were advisors to this project, and site principal investigators Drew Helmer, M.D., M.S., Laura Marsh, M.D., Amee J. Epler, Ph.D., Scott A. Cardin, Ph.D., and Michelle D. Sherman, Ph.D. They also thank Penny White, B.S., Lea Kiefer, M.P.H., Lorne Ryland, B.S., B.A., Rose Gonzalez, B.S., and Nyree Cunningham-Pullen, M.S., for assistance with data collection, and Carrie Edlund, M.A., M.S., Sandra Pope, Ph.D., M.P.H., and Cynthia Brace.