Mood and anxiety disorders affect at least 700 million people each year, which, together with other mental and substance use disorders, account for 7.4% of the world’s total burden of disease (

1,

2). Despite the size of the problem, only a small proportion of those affected seeks or receives evidence-based treatments (

3).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective at treating depression and anxiety disorders (

4–

6), but simply increasing the availability of individual face-to-face CBT cannot meet the needs of all people who require treatment (

7). Another strategy for improving access to CBT is to provide treatment online. Clinical trials show that therapist-guided Internet-delivered CBT (iCBT) produces clinical outcomes comparable with CBT delivered in face-to-face settings (

8–

10), and clinics using therapist-guided iCBT as part of routine clinical care report outcomes that match the gains observed in controlled trials (

11–

15).

As part of the Australian government’s e–mental health strategy (

16), the MindSpot Clinic was funded to provide online assessment and treatment as a routine clinical service to adult Australians with anxiety and depression. The clinic was designed to provide therapist-guided services to more than 10,000 people per year.

This article presents a prospective cohort study of the outcomes of the clinic in the first calendar year of operation and follows the STROBE (“strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology”) guidelines (

17). The clinical efficacy of the iCBT treatments provided by the clinic has been established in five published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (

18–

23). The study examined outcomes from the use of those treatments as part of routine clinical care. We expected that the treatment outcomes obtained in the RCTs would be replicated in the clinic.

Methods

Study Design and Ethical Review

This prospective noncontrolled observational cohort study included all eligible users of the clinic from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2013. Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Macquarie University.

Patients

Patients self-referred through the clinic Web site (

www.mindspot.org.au), which was promoted via links from health Web sites and paid online advertisements. Clinic services were provided at no cost to patients. Participants in this study were Australian residents who were eligible for publicly funded health services, who were at least 18 years old, who began assessment during 2013, and who agreed to the analysis and reporting of their deidentified data. Patients were required to complete an assessment before beginning treatment and were ineligible for online treatment if they were acutely suicidal, were engaged in regular psychotherapy, or had clinical presentations deemed to require comprehensive face-to-face assessment. People with subclinical symptoms were eligible for treatment at the clinic (

24–

26), as were those taking psychotropic medication.

Therapists

Therapists (N=20) had previous clinical experience of between one and 15 years. Most (75%, N=15) were nationally registered psychologists with a postgraduate or master’s degree in clinical psychology, and the others (25%, N=5) included nationally registered provisional psychologists in training, an indigenous mental health worker, and a counselor. Therapists received five weeks of training in the principles of online psychological assessment and treatment, as well as detailed instruction in the courses. Two part-time psychiatrists were available for consultation, supervision, and training. Therapists received an hour of individual supervision per week based on the clinical case management supervision model (

27), as well as group supervision and regular training workshops.

Procedure

Patients first created an online account and then completed an online assessment, providing demographic details and completing standardized self-report symptom questionnaires. In a small proportion (.5%) of cases, the assessment questionnaires were completed by telephone. Patients who completed the online assessment were invited to discuss their results with a therapist by telephone. A telephone-administered structured risk assessment was performed with all patients who reported suicidal intent or plans, and safety plans were developed for all patients to assist them to stay safe in the event their symptoms increased. Patients who identified as acutely suicidal were referred to local mental health services or emergency services, depending on the perceived urgency of the situation.

A summary of the assessment results, which identified clinically significant symptoms but which did not indicate diagnoses, was sent to the patient and to health professionals nominated by the patient. Patients were either supported to locate and access local mental health services or were invited to participate in a clinic treatment course. All patients were encouraged to visit their general practitioner for a physical review and to discuss the results of their assessment.

Clinic Interventions

Four iCBT treatment courses were offered: the Wellbeing course, designed to treat symptoms of anxiety and depression of adults ages 18–60 years (

19,

20,

28,

29); the Wellbeing Plus course, designed to treat symptoms of anxiety and depression of adults age ≥60 (

22,

23); the OCD course, designed to treat symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (

21,

30), and the PTSD course, designed to treat symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (

18). The iCBT treatment courses were developed and validated at a research unit, the eCentreClinic (

www.ecentreclinic.org).

Course choice was guided by the patient’s view of his or her main problem. Enrollment in the OCD and PTSD courses was offered after a telephone contact confirmed the presence of the relevant clinical features. The treatment courses were structured and based on principles of CBT and components of interpersonal therapy. Each course comprised four to six lessons and homework assignments, systematically made available over an eight-week period. Each lesson was presented as a series of slides that included didactic text and case-enhanced learning examples, photos and images that illustrated the principles of CBT, and supplementary material on related topics. Automated analysis of the text found that the content could be understood by most fifth-grade students.

Patients received twice weekly automated e-mails that reinforced progress and prompted practice of therapeutic activities. Each patient worked with the same therapist throughout the course, who provided weekly contact by secure e-mail, by telephone, or both. Each therapist had a caseload of 20–50 patients. Therapists followed manuals that provided scripted messages and key objectives for patient contact for each week of the course. At midtreatment, alternative treatments were discussed with patients who were not making progress.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (

31) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (

32). The PHQ-9 comprises nine items measuring symptoms of major depressive disorder on 4-point scales. Possible scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating increasingly severe symptoms of depression. A score of 10 on the PHQ-9 has been identified as the threshold for identifying

DSM-IV–congruent depression. The PHQ-9 has good internal consistency (

33) and is sensitive to change (

34). The GAD-7 measures seven items on 4-point scales. Possible scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater severity of anxiety symptoms (

35,

36). A score of 8 has been shown to be the optimum sensitive and specific threshold for the presence of an anxiety disorder (

37). The GAD-7 is sensitive to

DSM-IV–congruent generalized anxiety, social phobia, panic disorder, OCD, and PTSD.

Each week, patients completed the GAD-7, PHQ-9, and single-item measures inquiring about personal safety and treatment satisfaction. A larger battery of questionnaires, including a measure of psychological distress (ten-item Kessler Scale; K-10 [

38]), was administered at assessment, midtreatment, posttreatment, and three months posttreatment. The K-10 is commonly used in large general population surveys (

39); it has excellent internal consistency (

38). Scores on the K-10 range from 10, indicating no distress, to 50, indicating severe distress. The primary endpoint for assessing progress was eight weeks after the start of treatment (posttreatment), and the secondary endpoint was three months posttreatment (follow-up).

Data Collection, Management, and Analysis

Patient data were collected in an electronic database. Mixed linear models employing a Toeplitz covariance structure and maximum likelihood estimation (

40) were used to analyze overall changes across symptom measures. Completion of a treatment course was defined as reading the first four lessons of the Wellbeing and Wellbeing Plus courses, the four lessons of the PTSD course, and the first five lessons of the OCD course.

Noncontrolled within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d), based on estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals, were calculated from assessment to posttreatment and follow-up. Estimates of clinical significance were derived from observed scores at posttreatment and follow-up. When these were not available, the most recently available data were used. Clinical significance was assessed with a modified version of the reliable recovery criteria (

41). Reliable recovery was calculated for patients who scored over the clinical cutoffs on the PHQ-9 or GAD-7 at assessment and was defined as the proportion of patients who scored below the cutoff on that measure at posttreatment or follow-up while also showing reliable change. We assessed reliable change by using Jacobson and Truax’s reliable change criteria (

31), as described by Gyani and colleagues (

41). Patients needed to reduce their PHQ-9 score by at least 6 points and their GAD-7 score by at least 4 points for the improvement to be considered reliable. Reliable change was reported to identify patients who showed reliable improvements or deterioration, regardless of whether they met clinical cutoffs. All data were analyzed with SPSS, version 21.0.

Results

A total of 10,293 people commenced assessment during 2013. Of these, 1,757 did not complete the assessment and 1,364 did not consent for analysis of their data, were under age 18, or were excluded for other reasons. [A patient flow diagram in the online supplement provides details.] Of the remaining 7,172 patients, approximately 50% reported that they only wanted an assessment or were seeking information about local services, whereas 2,133 enrolled in a clinic treatment course and 2,049 commenced treatment (that is, they completed at least one set of questionnaires during treatment) and were therefore considered eligible for analysis.

Demographic Characteristics

Details of patients who provided consent and who began assessments (N=8,929) are shown in

Table 1. Mean age at assessment was 36.4±13.0, and age range was 18–86 years. The proportion of patients living in each state and territory, living outside major cities, and identifying as indigenous Australians (Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander) closely matched national statistics (

42,

43).

Symptoms and Treatment History

People presented with moderate levels of depression and anxiety and significant levels of psychological distress (

39) (

Table 1). At assessment, 2.4% (N=102 of 4,300) of patients answering the question reported suicidal thoughts as well as an intention or plan to self-harm. Approximately one-third (32.4%, N=2,213 of 6,822) of patients reported they had never spoken to a health professional about anxiety or depression.

Treatment Outcomes

A total of 1,271 of 1,793 patients (70.9%) completed the Wellbeing course, 141 of 175 (80.6%) completed the Wellbeing Plus course, 16 of 24 (66.7%) completed the OCD course, and 43 of 57 (75.4%) completed the PTSD course. Completed PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questionnaires were available as weekly data. A total of 1,197 of 2,049 patients (58.4%) completed posttreatment questionnaires, and 761 of 2,049 (37.1%) completed follow-up questionnaires.

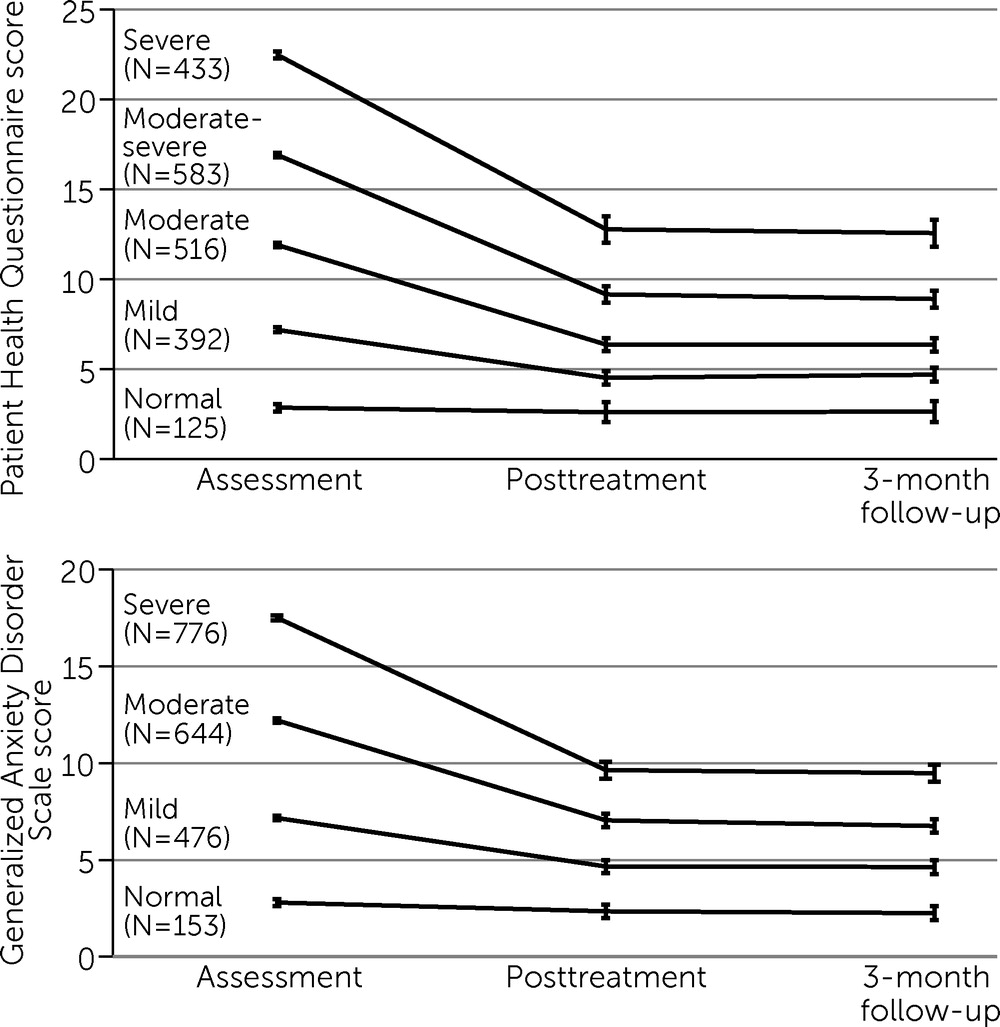

Table 2 presents means and standard deviations of observed data and estimated marginal means. For the PHQ-9, analyses revealed a significant main effect of time (F=147.72, df=2 and 2,944, p<.001). Paired comparisons revealed significant reductions in PHQ-9 scores from assessment to posttreatment (p<.001 for Wellbeing, Wellbeing Plus, and PTSD courses; p<.01 for the OCD course) and from assessment to three-month follow-up (p<.001 for Wellbeing, Wellbeing Plus, and PTSD courses; p<.05 for the OCD course).

For the GAD-7, there were significant main effects of time (F=127.13, df=2 and 2,946, p<.001). Paired comparisons revealed significant reductions in GAD-7 scores from assessment to posttreatment (p<.001 for Wellbeing, Wellbeing Plus, and PTSD courses; p<.05 for the OCD course) and from assessment to three-month follow-up (p<.001 for Wellbeing, Wellbeing Plus, and PTSD courses; p<.05 for OCD course).

Table 2 also presents noncontrolled within-group effect sizes, based on estimated marginal means.

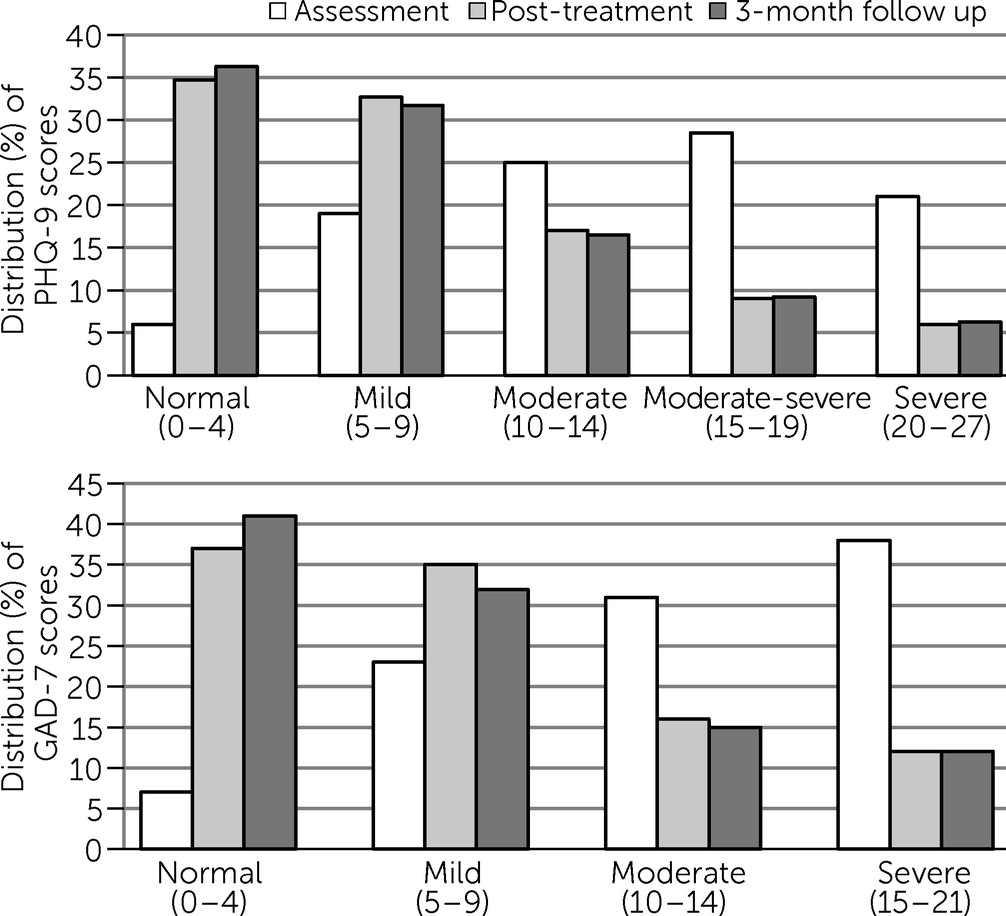

Figure 1 shows the change in the proportion of patients in each category of severity of symptoms on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 at assessment, posttreatment, and follow-up.

Figure 2 indicates that treatment was associated with a greater proportion of patients who moved to and stayed in the lower severity categories after treatment.

Clinical Significance

At assessment, 1,532 of 2,049 (74.8%) patients had PHQ-9 scores above the clinical cutoff (≥10), and 1,627 of 2,049 (79.4%) had GAD-7 scores above the clinical cutoff (≥8). At posttreatment, 783 of 1,532 (51.1%) showed reliable recovery on the PHQ-9, and 828 of 1,627 (50.9%) showed reliable recovery on the GAD-7. At follow-up, 759 of 1,532 (49.5%) patients and 759 of 1,627 (46.7%) patients met criteria for reliable recovery on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, respectively.

At posttreatment, 1,066 of 2,049 patients (52.0%) showed reliable improvement on the PHQ-9, whereas 945 of 2,049 (46.1%) showed no reliable change and 38 of 2,049 (1.9%) showed reliable deterioration. On the GAD-7, 1,195 of 2,049 (58.3%) showed reliable improvement, 784 of 2,049 (38.3%) showed no change, and 70 of 2,049 (3.4%) showed reliable deterioration. At follow-up on the PHQ-9, 1,078 of 2,049 (52.6%) showed reliable improvement, 929 of 2,049 (45.3%) showed no reliable change, and 42 of 2,049 (2.0%) showed reliable deterioration. On the GAD-7, 1,221 of 2,049 (59.6%) showed reliable improvement, 750 of 2,049 (36.6%) showed no reliable change, and 78 of 2,049 (3.8%) showed reliable deterioration.

Therapist Time and Treatment Satisfaction

Therapists spent a mean±SD of 111.8±61.6 minutes (range=40–412; median=93.5) per patient during treatment. An additional 60 minutes of therapist time was required on average for the assessment, administration, and follow-up. Patient satisfaction with treatment was measured weekly and was high. Of the patients who completed the posttreatment questionnaires, 1,146 of 1,197 (95.7%) reported that the course was worth doing, and 1,154 of 1,197 (96.4%) reported that they would recommend the course. Anonymous staff surveys have also shown a high level of therapist satisfaction.

Discussion

This article reports the results of iCBT treatments provided as routine clinical care in an innovative and high-volume online national service. The results replicated results obtained in the controlled trials. With the exception of the OCD course, the treatment courses achieved effect sizes >1.3 on measures of anxiety and depression and reliable recovery in 46.7%−49.5% of cases. The moderate effect sizes for the relatively small number of patients in the OCD course were similar to those observed in the controlled trials. These findings add to evidence indicating that iCBT treatments can be successfully provided as routine clinical care with efficacy equivalent to what was achieved in clinical trials (

11–

15).

In addition to replicating the results of the clinical trials, the improvements, as measured by effect size, recovery rates, and reliable clinical change, are comparable to benchmarks of outcomes from face-to-face CBT treatments (

4,

5,

44,

45). The results also compare well with other initiatives that involve the large-scale implementation of psychological treatments (

41,

46), and the high level of patient satisfaction indicates the acceptability of online treatment. The amount of therapist time spent during treatment indicates that the service is likely to be cost-effective in comparison with traditional services (

25) and thus is currently the subject of a health economics evaluation.

The experience of launching the clinic has advanced our understanding of the role of online mental health services. We had anticipated a high conversion rate from assessment to the treatment courses. Instead, the participation rate among clients who completed an assessment was about 30%, mainly because many of those completing assessments indicated that they wanted only an assessment or information about local mental health services, not online treatment. It emerged that the clinic provided several important services in addition to treatment, including a convenient way of screening symptoms, arranging for people in crisis to receive urgently needed help, and a way of informing people—many of whom had no previous experience of mental health care—about the availability of local services.

Limitations of this study included the absence of a control group, which would have informed rates of natural remission, although the results were similar to those of the treatment group in controlled trials. Another limitation was missing data, in that 8% of patients declined permission to analyze their data, and approximately 20% did not complete assessment. The rates of assessment completion were consistent with reports from another online clinic (

15), and our experience was consistent with that clinic’s observation that a considerable proportion of noncompleters did not wish to reveal personal information. We also observed lower rates of questionnaire completion at posttreatment and follow-up, compared with the original clinical trials, although the weekly data collected during the course were similar for the patients who did not complete follow-up questionnaires, suggesting similar outcome. A further limitation was the use of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 to measure change in the small number of people enrolled in the OCD and PTSD courses. Detailed description of the symptom measures specific to OCD and PTSD is the subject of a forthcoming paper.

Strengths of the study included the large sample collected over an entire calendar year as part of routine clinical care and the regular measurement of symptoms, allowing consistent measurement of treatment effects. Services were provided by mental health professionals with no prior experience in online treatment, and the trajectory of effect sizes for the treatment groups during the first year of operation suggests that outcomes are likely to improve as the clinic matures.