Depression is one of the most prevalent mental disorders, affecting one in six older adults in the United States (

1). Depressed older adults tend to have poorer functional status (

2) and utilize more health care resources than nondepressed older adults (

3). Furthermore, depression is a major contributing factor to the higher rate of suicide among older adults compared with middle-aged adults (

4). Although many patients receive care for depression from primary care clinicians, past research indicates that clinicians are more likely to attend to patients’ general medical health before addressing their mental health (

5). This issue is particularly relevant with regard to depression because depression is known to co-occur with general medical illnesses (

6), which may compete for clinicians’ time and attention.

Given that depression often goes unrecognized in primary care, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends conducting depression screening for adults if there are sufficient staff supports (

7). However, uptake of depression screening in primary care has been low (

8). This may reflect beliefs that assessment and management of general medical problems should take precedence over depression screening, concerns about providing follow-up care for patients who screen positive for depression (

9), and uncertainty about whether depression screening alone improves outcomes (

10).

In an effort to increase the rates of depression screening in primary care, Medicare included depression screening as a required component of each patient’s initial annual wellness visit (AWV). This benefit, instituted in 2011, allows time to “develop or update a personalized prevention plan” (

11). In order to encourage uptake, these visits are reimbursed at a higher revenue-value unit rate (

12). It remains uncertain whether having an AWV increases the likelihood of depression screening. In this cross-sectional study, we assessed whether having an AWV was associated with increased odds of depression screening in primary care after the analyses adjusted for patient factors and clustering at the physician and clinic levels.

Results

The study participants’ mean±SD age was 74±7 years; 62% were white, 59% were female, and 50% had at least one AWV. Type of visit differed by race but not by age or sex (

Table 1). In total, 526 patients (12%) had a depression screen during the index visit. Receipt of depression screening during the index visit did not differ by sex (N=214, 12%, for males, and N=312, 12%, for females). However, blacks were more likely than whites to be screened (N=368, 26%, versus N=153, 6%, p<.01). On average, patients who were screened for depression were significantly older than patients who were not screened (75±7 versus 74±7, p=.01). Adults with a non-AWV were more likely to be screened for depression compared with those with an AWV (N=315, 15%, versus N=211, 10%, p<.01).

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses

The regression model that controlled for age, sex, and race had the best fit and the smallest AIC and BIC on the patient level (

21). Adding health status variables did not improve the fit of the model, as assessed by using likelihood-ratio tests.

In a multivariable logistic regression not accounting for clustering by clinician, the OR for depression screening during the index visit changed with the inclusion of patient-level covariates. Specifically, after the analyses controlled for race, age, and sex, the OR for depression screening during an AWV changed from .64 to 1.30 (

Table 2). In addition, blacks had significantly higher odds of depression screening compared with whites in the multivariable model before it was adjusted for clustering (OR=6.47).

After accounting for clustering at the physician and at the physician-and-site level, patients with AWVs were not significantly more likely to receive depression screening than patients with non-AWVs. In addition, the racial difference in screening disappeared after the analyses adjusted for physician clustering. The intraclass correlation, which can be interpreted as the proportion of the variance in depression screening explained by differences among physicians, was very strong (.85), indicating the need to account for this source of variance by using multilevel models.

Site factors accounted for part of the variance between physicians in depression screening. Adjusting for site correlation decreased the within-physician intraclass correlation from approximately .85 to .45. The association of patient-level factors and depression screening was similar regardless of whether the model accounted for physician clustering or site-and-physician clustering (

Table 2).

Depression Screening by Site

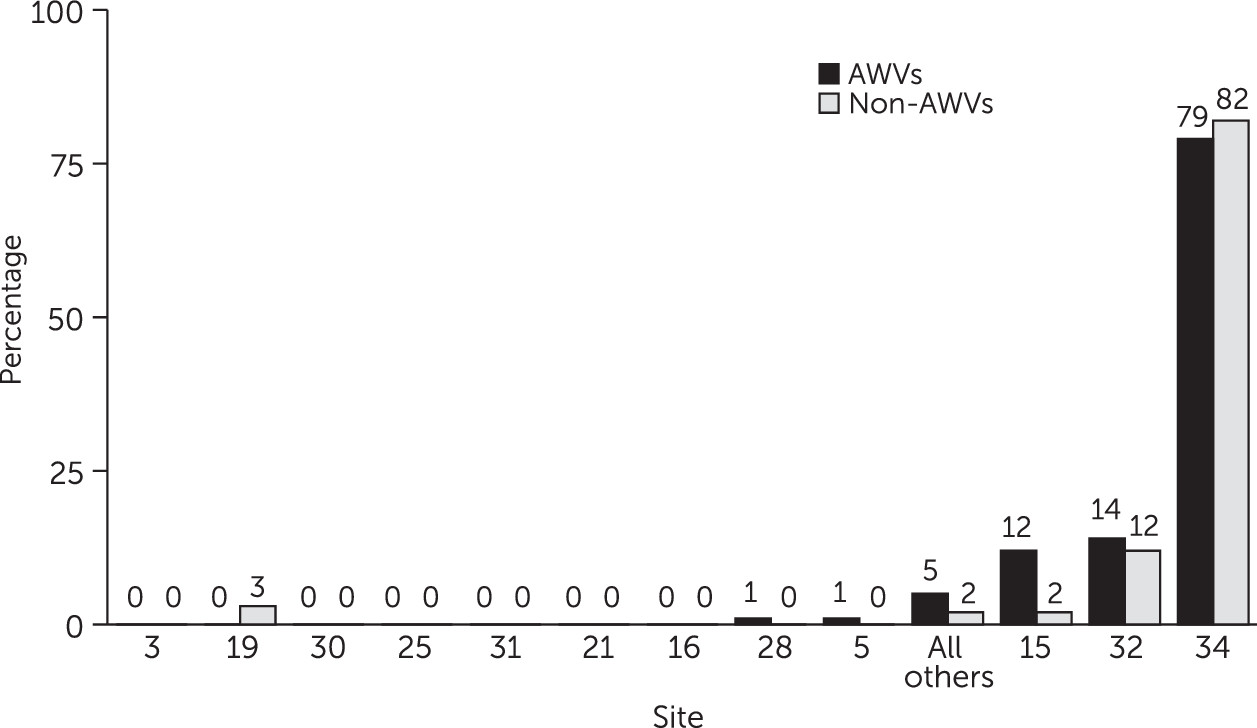

When depression screening by visit type was broken out by site (

Figure 1), a clear association between site and depression screening was found, with site 34 screening 79% of AWVs and 82% of non-AWVs within its site. Six sites did not screen for depression during any of the index visits, despite the fact that each had seen over 100 patients included in the study.

Sensitivity Analysis

In a sensitivity analysis, site 34 was found to have an important impact on the overall odds of depression screening. When only site 34 was analyzed, the odds of depression screening were lower for patients with AWVs compared with non-AWVs, after the analyses controlled for age, sex, and race (adjusted OR=.89). However, when the analysis excluded site 34 and controlled for age, sex, race, and site clustering, patients with AWVs had twofold greater odds of depression screening compared with patients with non-AWVs (

Table 3).

Discussion

This study found that overall rates of depression screening during AWVs were low (10%). A bivariable regression modeling the relationship between depression screening and visit type found that patients with non-AWVs had higher odds of being screened for depression than patients with AWVs. After adjustment for patient factors and clustering, the odds of depression screening for patients who had AWVs and patients who had other types of primary care visits were not significantly different. Screening for depression during a preventive care visit was strongly associated with physician and practice site. Without accounting for these additional clustering factors, patient-level factors, such as race, would have appeared highly associated with the odds of depression screening.

Surprisingly, there was a very prominent association between depression screening and clinic site, despite the AWV benefit. One site screened 79% to 82% of patients during the index visit, irrespective of whether the visit was an AWV or other primary care visit, and six sites screened none of their patients. The intraclass correlation among physicians in the regression models was very strong (.85), implying that a clinician’s propensity to screen was not affected by patient factors.

The findings suggest that simply providing patients with the opportunity to receive mental health preventive care through the AWV benefit is not sufficient to increase screening rates. Depression screening may be neglected because of barriers in incorporating screening into routine practice (

9). The sensitivity analysis found that the AWV benefit significantly increased the odds of depression screening among sites that had low overall screening rates (not site 34). However, as

Figure 1 indicates, this effect was not uniform across all sites, and seven sites did not screen for depression during any AWVs. Policy initiatives aimed at increasing depression screening should consider exploring ways to improve uptake of routine screening as part of the AWV for older adults.

Medicare established the AWV benefit in January 2011 as a way to increase access to preventive care. The AWV was not intended to replace a patients’ yearly physical examination but to provide time to discuss new or chronic medical conditions (

22). Depression screening is explicitly included as an essential task during a patient’s initial AWV (

13). Because this study took place in 2011 and 2012, and patients cannot have two AWVs within 12 months of each other, we are confident that the sample included patients’ initial AWVs. Other tasks included as part of the AWV are taking a patient’s history through a health risk assessment, establishing medical and family history, measuring a patient’s height and weight, identifying a patient’s clinicians, and detecting any cognitive impairment. Clinicians may prioritize other tasks over depression screening, especially because previous work has found that clinicians are concerned about the validity of depression screening tools and prefer clinical judgment in determining whether a patient is depressed (

23). There is also the possibility that patients refuse to be screened for depression because of the stigma associated with this diagnosis.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends depression screening only when “staff-assisted depression care supports are in place,” yet staff-assisted depression supports can be minimal, such as having a nurse notify physicians of a patient’s score (

7). Conversely, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care does not recommend routine depression screening for adults (

24). Furthermore, a systematic review found that screening for depression among older adults without “further care supports” is unlikely to improve depression outcomes (

25). The mixed message from various practice guidelines and research, plus the need for sufficient screening supports, may have contributed to differences in screening rates among clinicians. Indeed, a qualitative study found that clinicians reported concerns about how to screen for depression and about the lack of options available if a patient were diagnosed as having depression (

9). As shown in

Figure 1, one practice site was the main contributor to depression screens in this sample, regardless of the type of visit. At this site, there was a clinician-leader with a strong belief in screening, who established a clinical workflow that supported routine depression screening.

Past research suggests that variations in the delivery of health care may be indicative of poor quality of care (

26,

27). Physicians face competing priorities when deciding which services to recommend. They often need to consider a patient’s health care needs, organizational and financial barriers and facilitators, and mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of elements of care (

26). Recent work on clinic predictors of adopting a depression care improvement model in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs health system found that sites with poor communication among staff, fewer quality improvement processes, insufficient financial resources, and no psychologists or psychiatrists on staff had 40% to 62% reduced odds of adopting a depression care improvement model (

28). Thus improving the quality of depression care may require organizational changes far beyond the financial incentives associated with AWVs.

There were several limitations to this study. First, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis, and therefore no strong inferences regarding causation can be made. Second, patients’ chronic diseases were determined by using

ICD-9 codes, which are sensitive to physicians’ coding preferences. Third, the data did not include medication information, and therefore we could not assess changes to antidepressant medications. Other research suggests that depression screening is associated with increased prescription of antidepressants (

29).

Fourth, the external generalizability of the study is limited because it was conducted in a single health care system in Maryland and Washington, D.C. Nevertheless, we found large variations in screening practices even within this one system. These variations in screening practice are likely not unique to this health care system and would be found in other health care systems nationally. Finally, this study occurred during the first 20 months of the AWV benefit, and depression screening during AWVs may have increased since that time. Notably, the study identified strong clinician-level and site-level effects, which could be accounted for only by using multilevel models. This study’s ability to account for clustering within both clinicians and sites was a major strength of this work. However, future work should identify which clinic characteristics or processes are determinants of depression screening during AWVs.