There is growing concern over high rates of psychotropic prescriptions in juvenile justice settings and the adequacy of mental health services to youths in these settings (

1–

8). The juvenile justice system is part of the child behavioral health system of care (

9–

12), and many youths with mental health needs, especially youths of color, access mental health services through the juvenile justice system (

13–

15). Youths in juvenile justice settings have high rates of behavioral health concerns, and estimates of diagnosable disorders range from 50% to 75% (

16–

19). Although greater mental health needs support higher psychotropic prescribing rates, current data do not indicate how much higher the prescribing rates should be. Meanwhile, youths involved with the juvenile justice system are also at risk of unaddressed mental health needs (

7,

15,

20). Even though youths have a constitutional right to effective mental health services in juvenile justice placements and despite the existence of published standards and guidelines (

21–

23), many programs do not have adequate mental health services or health and mental health care policies and may not utilize best psychiatric practices (

24–

27). Furthermore, U.S. Department of Justice investigations and plaintiffs’ lawsuits concerning conditions of confinement in numerous juvenile justice facilities have found inadequate and inappropriate psychotropic and behavioral health practices (

7,

27–

30).

On a given day, approximately 61,000 youths reside in juvenile justice facilities, and states spend approximately $5.7 billion per year to incarcerate youths (

30,

31). In one juvenile justice facility, over 80% of the medication budget was spent on psychotropic medications (

32). Many psychotropic medications have limited efficacy and safety data for youths and may have significant side effects (

33,

34). Stakeholders have scrutinized child welfare system psychotropic prescribing practices. Juvenile justice–involved youths share many of the same risk factors as youths in foster care, including exposure to trauma, and large percentages of youths in the juvenile justice system have concurrent or previous child welfare system involvement (

35–

39). Psychotropic prescribing information for youths in juvenile justice placements is not readily available, as it is for youths in foster care. Prescribing information is limited in part because under federal law, Medicaid benefits must be terminated or suspended when youths are adjudicated to juvenile justice facilities (

40), and states are not required to report juvenile justice prescribing information. As a result, there is no uniform or searchable national juvenile justice prescribing database.

Integrating effective psychiatric and psychosocial treatments can address mental health needs while limiting medication costs, and integration produces better outcomes than either treatment alone for some conditions commonly seen in juvenile justice settings (

41,

42). Disruptive behavior is one of the most common problem behaviors of youths in residential juvenile justice programs (

43) and is also one of the most common reasons for prescribing antipsychotic medications for youths (

44). The most effective psychosocial interventions for youth disruptive behavior are cognitive-behavioral treatments and parent and youth skills training (

45). Guidelines for treating aggression with antipsychotics advise providing psychosocial intervention first (

46,

47). Although there is growing evidence that antipsychotic medications are more effective than placebo in reducing disruptive behavior in various youth populations, direct comparisons among antipsychotics, behavioral interventions, and combined treatments are limited (

33,

48–

50).

Psychiatric Practice Guidelines

The following psychiatric practice guidelines were developed and implemented in a state-run juvenile justice facility (facility A) in 2004 to promote evidence-based and promising psychiatric practices: screen for psychiatric conditions, especially those responsive to psychotropic medications. Partner with youths and parents in medication and mental health treatment decisions. Integrate and coordinate psychotropic and psychosocial treatments. Treat youth aggressive and disruptive behaviors primarily with skills training and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). Use rating scales to help with screening, evaluation, and assessment of medication response. Prescribe antipsychotics generally only to youths with psychotic or bipolar disorders, and prescribe mood stabilizers only to youths with bipolar disorders. Assess sleep problems with sleep logs and by staff report. Treat sleep problems initially through sleep hygiene and CBT. When prescribing for insomnia, first use medications with more benign side effects. Monitor medications and side effects per protocol.

The psychiatric practice guidelines are founded on evidence-based practices and the appropriate role of psychotropic medications in treatment. Universal and selected screenings are used to help identify youth behavioral health needs, which are common in juvenile justice settings and often unidentified. The guidelines specify that psychosocial interventions are the primary treatments for disruptive and aggressive behavior and discourage an inappropriate emphasis on medications. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s Atypical Antipsychotic Medication Practice Parameter (

51) highlights the lack of substantial empirical support for the use of second-generation antipsychotics for disruptive behavior of youths and recommends consideration of other psychosocial or pharmacological treatments with more established efficacy and safety before use of antipsychotics. The diagnosis of bipolar disorder among youths is controversial (

52). Given the lack of efficacy of mood stabilizers in “broad phenotype” bipolar disorder (

53–

55), the guidelines limit the use of mood stabilizers to youths who meet criteria for the “narrow phenotype.” Judicious use of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers can reduce side effects and risks for youths with conditions that can be effectively treated with psychosocial interventions.

The guidelines value the voices of youths and families in decision making about mental health treatment and psychotropic medications. This strengthens youth and family engagement in treatment, ownership of treatment decisions, and adherence to psychotropic medications after release. Facility A also emphasizes integration of medical and psychosocial treatments. Integration efforts include frequent communication among all staff, individual youth care conferences and consultations, and weekly multidisciplinary meetings to discuss clinical and administrative concerns.

This study examined the implementation of psychiatric practice guidelines in a state-run juvenile justice facility. Two other state-run juvenile justice facilities were used for comparison. All three facilities in this study use a treatment model based on CBT-DBT. An earlier version of this model has been described (

56). Only facility A implemented the psychiatric practice guidelines, providing an opportunity to examine the effect of the guidelines on psychotropic medication costs and youth aggression in sites with relatively similar treatment milieus. This study assessed the impact of psychiatric practice guidelines on medication costs and youth aggression in a juvenile justice facility.

Methods

This study retrospectively examined administrative data from January 1, 2003, through December 31, 2012, from three Washington State Juvenile Justice and Rehabilitation Administration (JJRA) residential facilities: facility A, a medium–maximum security facility housing younger male offenders and female offenders of all ages; facility B, a medium–maximum security facility housing older male offenders; and facility C, a medium security facility housing male offenders of all ages. All three facilities used the same pharmacy, pharmacy practices, pharmacist consultation, medication pricing structure, and unrestricted formulary over the study period. All three facilities use a treatment model based on CBT-DBT and aggression replacement training, and all three employ psychiatrists and psychologists. Information on youth treatment prior to adjudication was not available but was presumed to be highly variable.

Medication costs were used as a proxy for medication use because more detailed and specific information on medication prescriptions was not available. Monthly psychotropic medication costs were taken from administrative billing data and divided by facility census.

Table 1 presents data on the census of facilities across time points. From 2011 to 2012, facility A housed the most youths (N=4,835), followed by facility B (N=3,756) and facility C (N=2,216). Demographic data for JJRA youths were available only from 2008 to 2012; however, data for those years are likely similar to data for preceding years. Across the three facilities in 2008–2012, most youths were Caucasian non-Hispanic (38.6%), followed by African American (27.2%), Hispanic (16.5%), mixed (10.7%), Native American (2.8%), Asian (2.7%), and other (1.6%). Across the three facilities in 2008–2012, the sample was largely male (84%) and English speaking (98%). The mean±SD age was 15.9±1.4 years.

In addition to psychotropic medication costs, mental health acuity scores were determined for each facility from 2003 to 2012. Facility mental health acuity was aggregated by month from youth scores on a JJRA internally developed tool, the Diagnostic Mental Health Screen (DMHS). The DMHS is a 25-item measure that gathers information on past mental health treatment as well as current symptoms of depression, suicidality and self-harm, anxiety, thought disorders, attention-concentration, psychotropic medication use, drug and alcohol use, and mental status. Facility-level aggression scores were calculated by summing all reported aggression-related incidents within each facility per month and dividing by monthly census. Aggression-related items include threats of violence, youth-on-youth fights, staff assaults, youth assaults, serious disturbances, and incidents related to sexual aggression. Aggression data were available only from 2007 through 2012, and aggression analyses are restricted to this period. This study was reviewed and determined exempt by the Washington State Institutional Review Board (project E-062813-S).

Missing medication cost data were imputed by using linear interpolation, which has been shown to perform well as a missing data replacement technique by producing reasonable estimates of level and slope (

57,

58). Interpolation replaces the missing values with the mean of the nearest points (months immediately preceding and immediately following the missing points) and was used to replace medication cost data for five nonsequential months at facility A and four nonsequential months at facility C. Missing data for facility mental health acuity scores were estimated by using linear regression, trend at point, which replaces missing values with predicted scores based on the facility’s regression line. Acuity data were missing for sequential months within all facilities for the final six months of the study. The distribution curves, scale means, and standard deviations closely matched the original, nonimputed scales for both medication costs and acuity scores.

This study’s first hypothesis, that facility A’s psychotropic medication costs would decrease over time while facility B’s and facility C’s remained constant, was tested by comparing the medication costs across facilities over time while controlling for facility acuity levels by using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with medication costs as the dependent variable. Analyzing the time series data as a dependent variable raises the possibility of autocorrelation error due to temporally related data. This possible nonindependence of observations was managed by including both facility and time in the ANCOVA model. Time was divided into five periods: 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010, and 2011–2012. The time frames were constructed so that medication costs prior to the implementation of the medication management plan at facility A (2003–2004) could be compared with time periods following implementation. Two-year increments were chosen to identify trends over time while preserving enough observations within periods to power the analysis.

A bivariate correlation between the mean level of aggression incidents and acuity indicated no significant relationship. Because of this, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare aggression across facilities by time points in order to examine this study’s second hypothesis, whether the rates of aggression incidents over time differed among the three facilities. Aggressive incidents were derived from administrative incident data available from 2007 through 2012; consequently, the analyses were limited to this time frame.

Results

Psychotropic Medication Costs

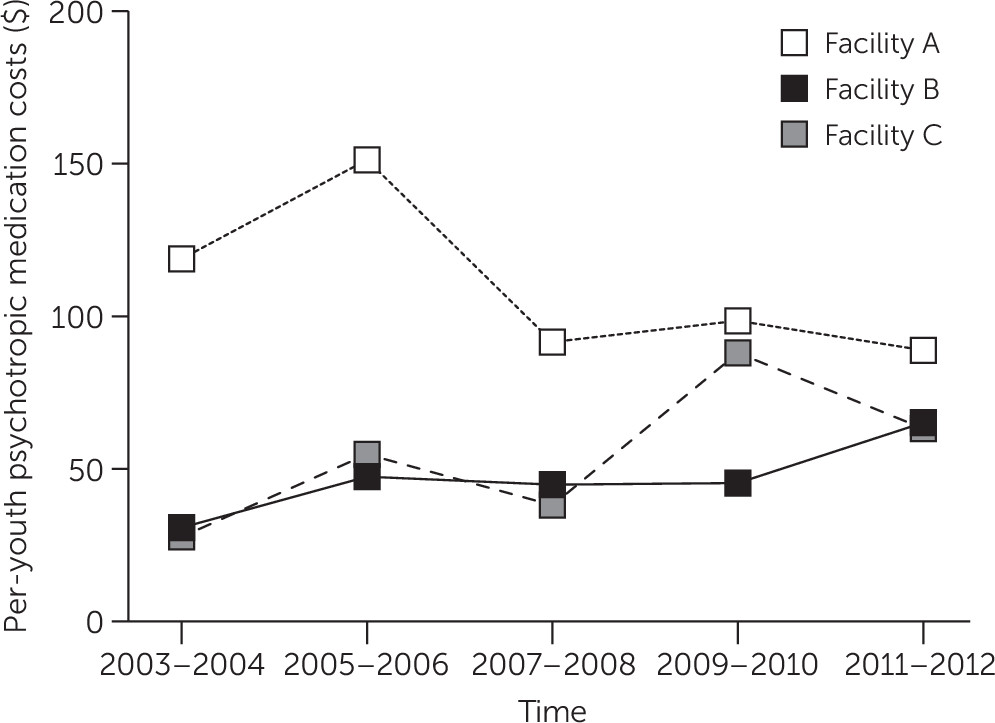

All three facilities increased in per-youth medication costs in the period following the implementation of the revised medication guidelines (

Table 1). In the first period (2003–2004 to 2005–2006), facility A’s costs increased by 27%, facility B’s by 53%, and facility C’s by 85%. Although costs at all three facilities increased during this time, facility A had the lowest rate of growth. In the third period (2008–2009), facility A’s costs dropped by 35%, whereas facility B’s costs remained relatively level and facility C’s costs increased by 59%. During the fifth time interval (2011–2012), facility A’s costs continued to fall. Compared with costs in 2003–2004, facility A’s costs dropped by 26% overall, facility B’s costs increased by 104% and facility C’s costs increased by 152% (

Figure 1).

A significant bivariate correlation was found between mental health acuity and medication costs (r=.49, p<.001

). Consequently, medication costs were adjusted for facility acuity levels in the subsequent model. An ANCOVA analysis that controlled for mental health acuity with facility and time as fixed effects identified a significant interaction effect between facility and time (p<.001), in addition to a facility main effect for medication costs (p<.001) and a main effect for time (p<.001) (

Table 2). The partial eta-squared effect sizes were strongest for the overall differences in facility (.38) followed by the facility × time interaction (.34). Both of these effect sizes indicate very strong differences between sites. For the purposes of this study, the facility × time interaction is the most pertinent because it indicates a pattern of decreasing medication costs at facility A after implementation of prescribing guidelines, an effect not observed for the other two facilities.

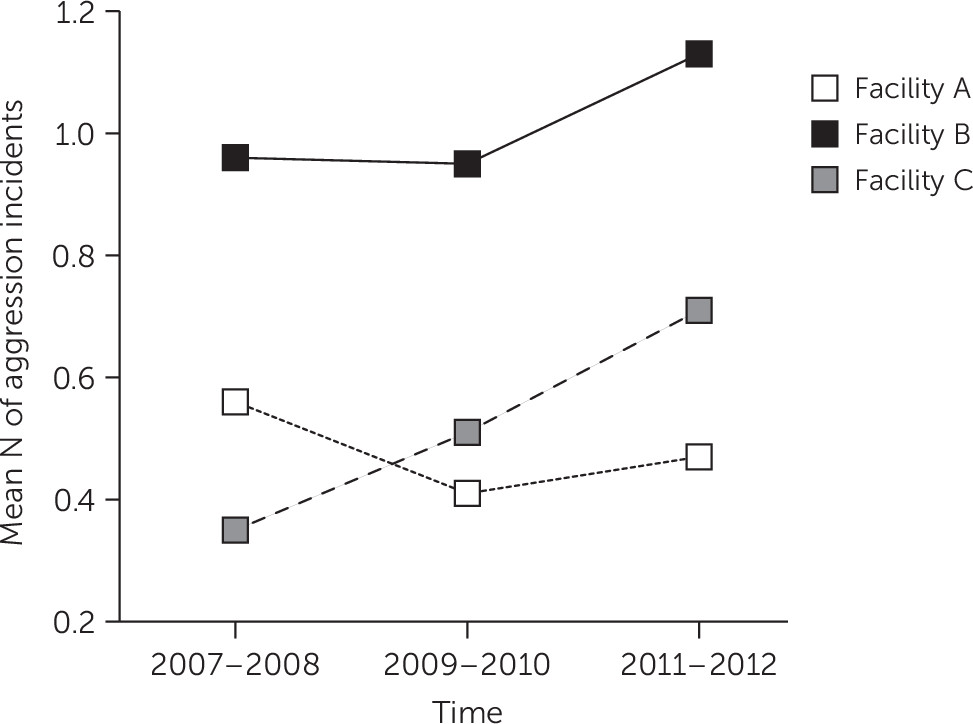

Aggression-Related Incidents

Aggression incident reporting was available only from July 2007 through the end of the study. This coincides with the time when facility A began to experience a steady drop in costs, costs at facility B remained temporarily stable, and facility C’s costs increased. The trend in aggression incidents from 2007 indicates that facility A incidents did not change over time, despite decreasing medication costs. Although both facility B and facility C observed increases in aggressive incidents over time, facility A’s incident levels dropped from 2007–2008 to 2009–2010 and then remained stable (

Figure 2). An ANOVA indicated significant main effects for facility (p<.001) and time (p<.001) (

Table 2). These effects indicate that the facilities were significantly different from each other in total incidents, aggregated over all time periods, and that aggression levels changed over time. However, no facility × time interaction was identified.

Discussion

This study found that implementing psychiatric practice guidelines in a juvenile justice facility was associated with a reduction in psychotropic medication costs without an increase in youth aggression. Some have argued that inadequately trained staff or limited access to effective psychosocial treatments may contribute to higher rates of prescriptions among high-risk youths (

59,

60). The guidelines require an organized treatment milieu to support a biopsychosocial approach and avoid a disproportionate emphasis on prescribing to manage behavior. This study’s findings are consistent with previous reports that reducing psychotropic medications in non–juvenile justice residential treatment settings with organized treatment milieus does not lead to an increase in negative behaviors among youths (

61–

63). This study extends the knowledge base by achieving positive outcomes in a juvenile justice setting, specifying practice guidelines, and using a comparison site design.

This “study of convenience” used cost as a proxy for the level of psychotropic prescribing, but the goal of the guidelines is not to reduce prescriptions or costs. In some cases, the preferred practice is more costly, such as use of a single daily dose of a long-acting stimulant rather than multiple doses of immediate release to increase the likelihood that medication will be taken as prescribed after release from residential treatment. The goal of the guidelines is to “right size” medications on the basis of benefit-risk considerations. This “right sizing” is akin to the “principle of sufficiency”—that youths should be prescribed the medication or medications that they need and no more (

61,

63). “Right sizing” also recognizes that psychotropic medications may be both over- and underutilized (

26,

59). Although some prescriptions were discontinued in facility A, the guidelines stress that medications are important in behavioral health treatment. The guidelines emphasize identifying and treating youths with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), given the effectiveness of ADHD medications in improving disruptive behavior, psychosocial functioning, and adult arrest rates (

41,

64,

65). The guidelines also highlight screening and assessing for other medication-responsive conditions and offering indicated medication trials. Although some youths were started on anti-ADHD medications or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in facility A, overall cost reductions likely resulted from discontinuing antipsychotic and mood stabilizer prescriptions that were started prior to adjudication for youths without specific indications. Connor and McLaughlin (

62) reported a similar pattern of reducing antipsychotic and mood stabilizer prescriptions in residential treatment. Expiring medication patents also contributed to lower medication costs, but costs at facilities B and C increased over the study period.

This study had several limitations. This convenience study used a post hoc analysis of existing program evaluation data points that were limited in time scope and specificity, and missing data were imputed. Aggression incidents, medications, costs, diagnoses, and mental health acuity could not be analyzed at the level of the individual, and facility prescription rates could not be calculated. Consequently, youth characteristics predicting good or poor response to the guidelines could not be assessed. Although aggression incidents were one of the primary outcome measures, psychotropic medications may be prescribed to target symptoms other than aggression, and the youths who were prescribed medications may not be those who were involved in aggression incidents. The appropriateness of medication prescriptions could not be evaluated with available data. The three study facilities have populations that differ by age, gender, and severity of mental health problems. Postrelease information on youth prescriptions, symptoms, and psychosocial functioning were not available. Findings may not generalize to other juvenile justice or residential treatment facilities that do not have organized psychosocial treatment programs or that serve youths with different characteristics. Future studies should proactively track prescriptions, behaviors, and diagnoses of individual youths over time and assess outcomes beyond aggression, including increases in prosocial behavior and other aspects of psychosocial functioning.

Given the limited information available on psychiatric prescribing practices in juvenile justice facilities, high prescribing rates for youths with disruptive behavior, and concerns over the adequacy of juvenile justice rehabilitation, this study provides support for integrating best prescribing practices with organized psychosocial treatments. This study’s findings can also inform the treatment of other high-need youths, who may benefit from psychotropic “right sizing,” including youths in the child welfare system. Potential benefits of an integrative approach include discontinuing unneeded medications; avoiding short- and long-term medication side effects and risks; and achieving better health outcomes, enhanced youth skills, fiscal savings, and improved long-term juvenile justice and psychosocial outcomes.

Conclusions

Implementing evidence-based psychiatric practice guidelines in a juvenile justice facility with an organized psychosocial treatment program can reduce psychotropic medication costs. Cost reductions were achieved even as some youths were started on medications. The reduction in psychotropic medication costs was not associated with increases in youth aggression. This study provides support for integrating best prescribing practices with organized psychosocial treatments in juvenile justice settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Jennifer Redman, M.S., and Eric Jenkins, B.A., with the Washington State Rehabilitation Administration for their support of data access.