Common mental health conditions seen in primary care, such as depression and anxiety, impose substantial suffering, complicate coexisting general medical conditions (

1–

3), and lead to enormous loss of productivity (

4,

5) and increases in total health care costs (

6,

7). Primary care has long been recognized as the de facto mental health treatment setting (

8,

9). However, the average quality of mental health care in primary care remains lower than optimal (

10,

11).

The collaborative care model (CCM) incorporates the core concepts of the chronic care model (

12,

13) to address the need to integrate high-quality mental health care in primary care. Over 70 randomized controlled trials have provided collective and robust evidence of the effectiveness of CCM to improve depression, processes of care, and quality-of-life outcomes (

14,

15) and of its potential for reducing long-term health care costs (

16). The CCM approaches care with a collaborative team, including the primary care physician, a care manager, and a consulting psychiatrist. The key principles of the model include systematic follow-up of patients by the care manager, measurement-based care that uses symptom rating scales to track clinical improvements or identify patients who are not improving (

17), and “stepped care” (

18) with which treatment is systematically adjusted or intensified (by the primary care team but with input from the consulting psychiatrist) for patients who are not improving (

19). The CCM is increasingly recognized as a best practice to integrate evidence-based mental health care into primary care (

20–

23).

Wide dissemination of the CCM, however, may be hindered by the complexity of the intervention and a lack of knowledge regarding the relative importance of the different components of the model for patient outcomes. The CCM is defined by a set of core components and tasks (

24,

25) and has almost always been tested as a package. Provider organizations with limited experience of practice changes may not be able to achieve full fidelity when first implementing CCM (

26,

27). Knowing the relative contribution of key elements of the model would help provider organizations direct their resources to maximize returns on their implementation. Such knowledge would also inform the selection of quality assurance and performance evaluation measures for CCM implementation.

A limited number of studies have sought to identify “active ingredients” of CCM that disproportionately contribute to its effectiveness (

28–

31). The ingredients examined were mostly structural aspects of the intervention (for example, use of a clinical information system). Studies of process-of-care elements (for example, intensity and frequency of care manager contacts) are important to guide the operation and quality assurance of the CCM, but such studies have been rare (

32). Furthermore, analysis of process-of-care measures aggregated to the provider or site level, as in the work of Bauer and colleagues (

32), could be subject to one type of ecological fallacy: average measures that lack variation across studies or implementations could disguise large variation within these units that might have important implications for patient outcomes (

33).

In this study, we began to address this knowledge gap by identifying and examining two key process-of-care tasks of CCM and by exploiting variation across patients by using data from a large implementation in Washington State. We tested the hypothesis that practice of either of the two tasks predicts clinically meaningful improvement in depression within six months of CCM initiation.

Methods

Selection of Key Tasks

We first compiled a list of process-of-care components and key tasks of CCM on the basis of expert consensus (

25). We focused on tasks that can be reliably measured with the Clinical Management Tracking System, the clinical information system (

34) first developed as part of the Improving Mood–Promoting Access to Treatment (IMPACT) study (

35) and subsequently used in many CCM implementations (

Table 1). We then applied the following criteria to select key tasks to be studied. First, the tasks should embed one or more of the key principles of the CCM, including systematic follow-up, measurement-based care, and stepped care. Second, the tasks should occur in the early stage of CCM (first 12 weeks) when care management is most intensive (

36) and likely most influential in shaping patient outcome trajectories (

32). Restricting selection to tasks performed in the early stage may also mitigate the selection bias introduced by the stepped-care nature of CCM, in that patients whose depression is resistant to treatment subsequently receive more intensive care management, but because of the nature of their conditions, they are less likely to achieve good outcomes. Third, the tasks should be of significance to all CCM patients regardless of whether they receive medication or psychotherapy (or both). Fourth, substantial variation should exist in the practice of these tasks in our data (<90% in fidelity) to enable reliable estimates.

Two key process-of-care tasks were selected: at least one follow-up contact with the patient by the CCM care manager within four weeks of the initial contact, either at the clinic (in person) or by phone (reflecting the principle of systematic follow-up); and at least one psychiatric consultation on the case between weeks 8 and 12 for patients who do not achieve improvement by week 8 (reflecting measurement-based care and stepped care). Restriction to patients who are not improving for the second task was based on the CCM protocol that recommends psychiatric consultation for cases in which patients do not respond to initial treatment.

Study Population and Data

Our data were from Washington State’s Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP), a publicly funded implementation of the CCM in a network of more than 100 community health centers that are diverse in geographic location, size, and patient populations served (

37). First started in 2008, the MHIP has served more than 35,000 patients with mental health, substance abuse, and comorbid general medical conditions who received primary care in participating clinics (

38). Eligible patients included enrollees in the state’s Disability Lifeline Program (patients temporarily disabled because of a general medical or mental health condition and expected to be unemployed for 90 days or more), veterans and their family members, uninsured persons, low-income mothers and their children, and low-income older adults (the categories are not mutually exclusive). All participating clinics used a Web-based registry to systematically document care management activities and clinical outcomes on the basis of standard measurement tools (for example, the Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] to track depressive symptoms [

39] and to assist with population management).

In this study, we focused on patients age 18 or older who initiated care in the MHIP between January 1, 2008, and August 15, 2010, in clinics in King and Pierce counties, the two most populous counties in Washington State and where MHIP implementation first started. We further restricted to a subset of patients who had a baseline PHQ-9 score of ≥10, indicating clinically significant depression, and at least one follow-up contact with the MHIP care manager within six months (24 weeks) of the initial contact to ensure at least one chance to measure patient depression outcomes. The resulting sample included 5,439 patient-episodes.

Outcome Measures

Our main outcome measures were a binary outcome of achieving clinically significant improvement in depression, defined as having at least one follow-up PHQ-9 score of <10 or achieving a 50% or more reduction in the PHQ-9 score (

39) within 24 weeks of the initial contact with the MHIP care manager (“improvement” hereafter), and time to achieving improvement.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analysis.

We compared the probability of achieving improvement in depression by the receipt of either of the two key tasks defined above. We generated Kaplan-Meier survival curves to capture the cumulative percentage of patients achieving improvement over the first 24 weeks after initiation by the receipt of either task.

Multivariate analysis.

We estimated logistic models for achieving clinically significant improvement within 24 weeks and Cox proportional hazard models for time to improvement. Both models controlled for patient age and gender; baseline PHQ-9 scores; comorbid behavioral health conditions other than depression, including anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, cognitive disorder, psychosis, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and suicidal ideation; and categories of eligibility for MHIP. All multivariate analysis included dummy indicators of community health centers and MHIP participating sites (site fixed effects) to control for any between-site differences in quality and outcomes of care; the analysis derived robust standard errors taking into account clustering of patients within sites (

40,

41).

Propensity score adjustment.

Our initial analysis indicated that patient receipt of either task was associated with greater baseline severity of depression, behavioral health comorbidity, and MHIP eligibility categories. Although such association is consistent with the principle of stepped care, the resulting confounding would likely have biased our estimates. We thus conducted propensity score–adjusted analysis (

42) by constructing propensity score–matched control groups for each of the two tasks of interest. Predictors in the propensity score model for each task included all baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics and MHIP site fixed effects. We used 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching within a defined caliper (.25 of SD of the log-odds of estimated propensity scores) (

43,

44) with replacement, which allowed patients not receiving the task (the “controls”) to serve as matches in more than one pair. This approach, compared with other methods of matching that we tested (including 1 to k matching with replacement with and without a specified caliper), yielded both the most balanced sample and adequate sample size.

Results

Table 2 summarizes data on sample characteristics by receipt of either of the two CCM tasks. Patients receiving at least one follow-up contact in the first four weeks, compared with patients who received none, had slightly higher PHQ-9 scores, had a greater prevalence of all comorbid behavioral health conditions, and were more likely to be in the eligibility categories of Disability Lifeline clients and uninsured clients than in the other eligibility categories. Similar differences were noted in baseline severity and comorbidities by the receipt of psychiatric consultation in the subsample of patients not achieving improvement by week 8. Overall, 42.8% of patients with at least one follow-up contact in the first four weeks achieved clinically significant improvement in 24 weeks, compared with 34.4% among those who had no follow-up within four weeks. Among patients not improving by week 8, 24.9% of those with at least one psychiatric consultation between weeks 8 and 12 achieved improvement compared with 20.1% among those who did not receive consultation.

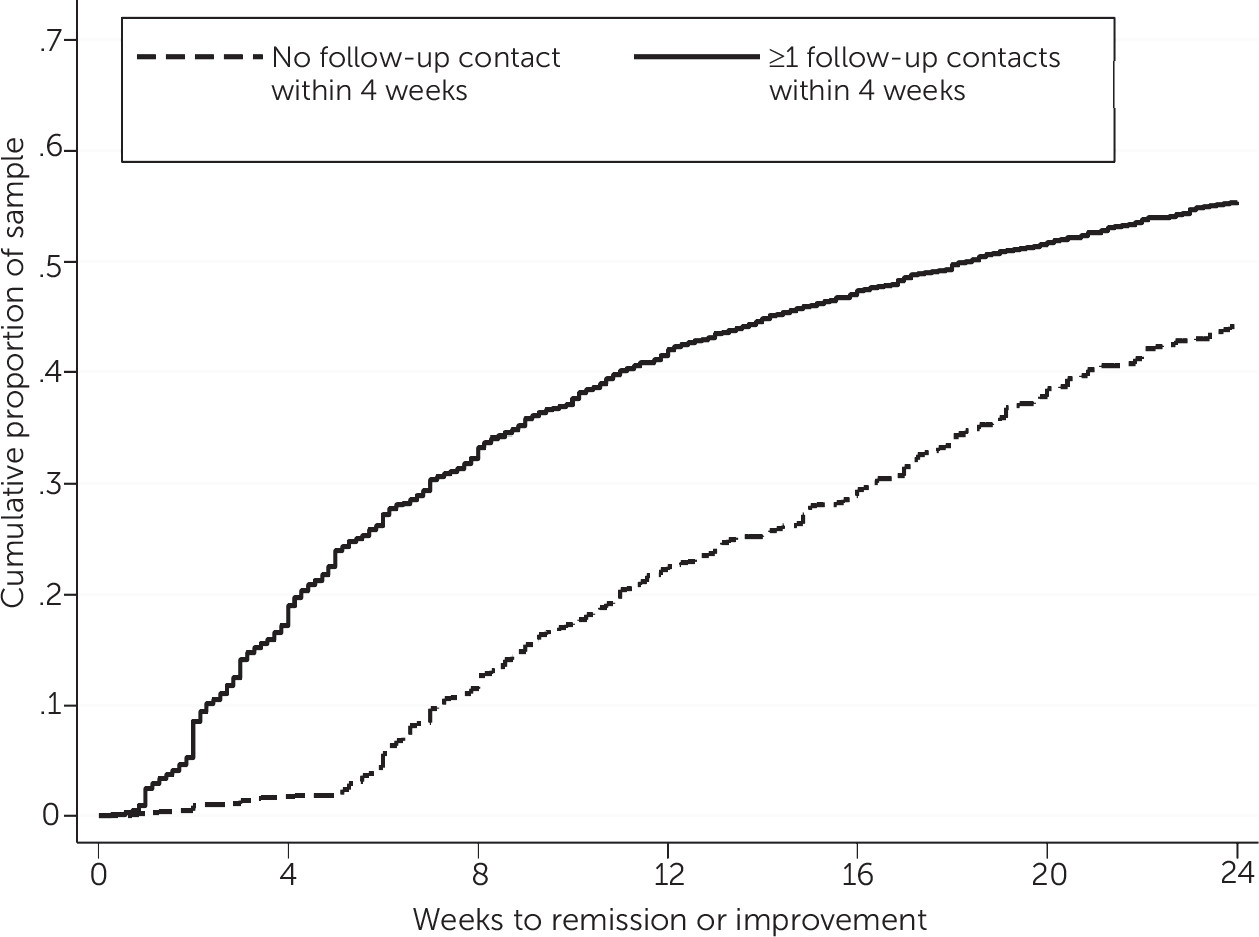

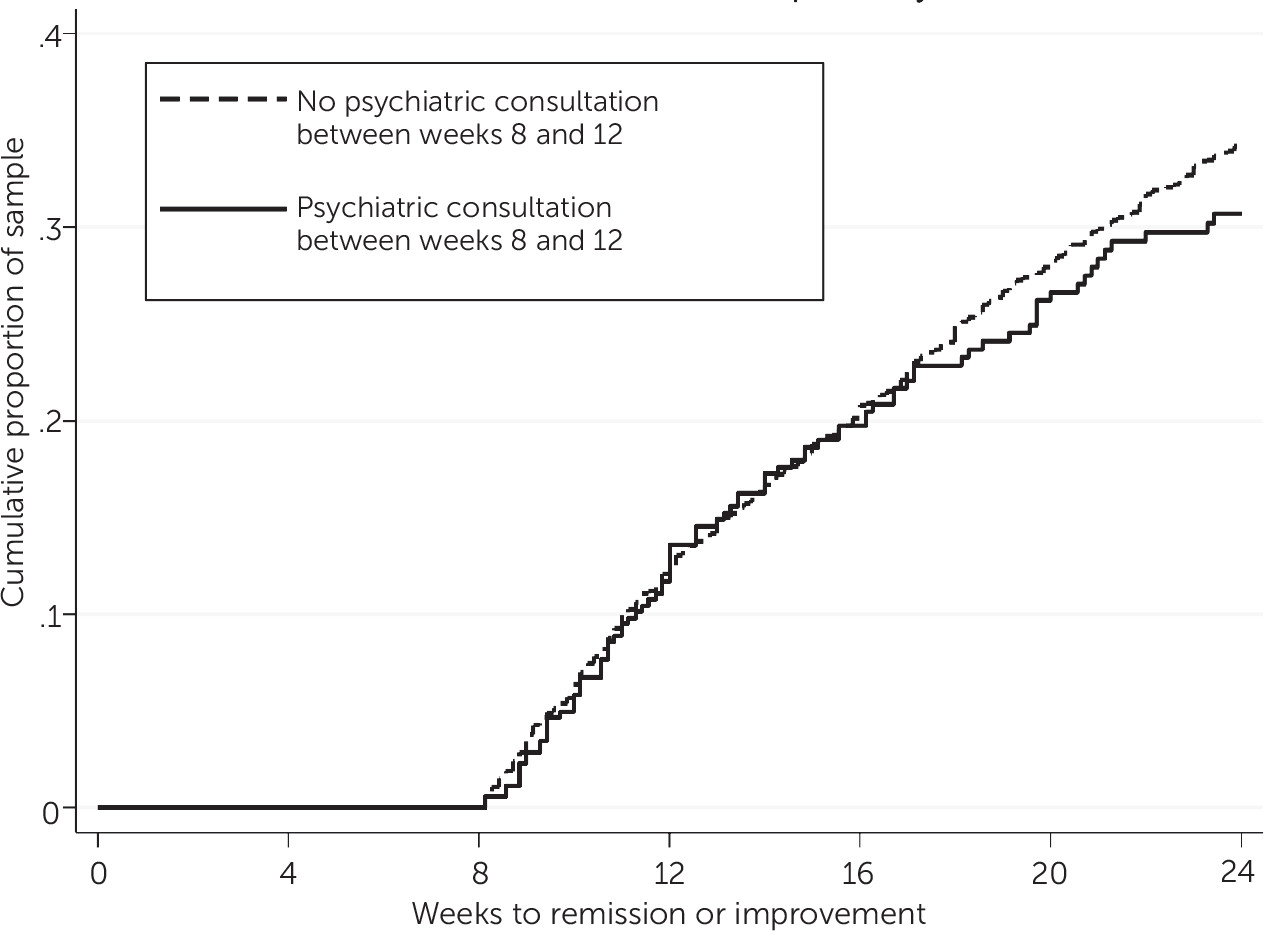

Figures 1–

2 are Kaplan-Meier survival curves for time to first clinically significant improvement in depression within 24 weeks. Having at least one follow-up contact within the first four weeks was significantly associated with a shorter time to improvement (log-rank test, p<.001). The cumulative percentage of patients achieving improvement was 10 to 20 percentage points greater among patients with at least one follow-up than among those without (

Figure 1). Having a psychiatric consultation, on the other hand, was not associated with a shorter time to improvement, as shown by largely overlapping survival curves in

Figure 2.

On the basis of multivariate logistic analysis, having at least one follow-up contact was associated with greater odds of achieving improvement in 24 weeks (odds ratio [OR]=1.63) (

Table 3). Among patients not improving by week 8, having a psychiatric consultation between weeks 8 and 12 was also associated with greater odds of achieving improvement in 24 weeks (OR=1.44). On the basis of estimated Cox proportional hazard models, having one or more follow-up contacts in the first four weeks was associated with a shorter time to improvement (hazard ratio=2.06) (

Table 3). The hazard ratio associated with psychiatric consultation was not significant. [Complete estimates for both models are presented in an

online supplement to this article.]

Our propensity score–matched samples achieved good balance in all observed baseline characteristics. The propensity score–adjusted analysis generated results very similar to those based on the original samples (

Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we used data from a large implementation of the CCM to examine whether the practice of two key tasks in the early phase of CCM intervention predicted patient depression outcomes. We found that timely care manager follow-up within the first four weeks strongly predicted clinically significant improvement in depression within six months and a shorter time to achieving improvement. For patients not achieving improvement by week 8, we found that psychiatric consultation within the next four weeks (weeks 8–12) strongly predicted improvement within six months but not time to improvement.

Our findings regarding timely follow-up in the first four weeks suggest that patient engagement in the early phase of treatment might have critical implications for patient outcomes. Three pathways are potentially at play. First, as is the case with most CCM protocols, patients were referred to the MHIP program at a time when they were acutely depressed. Timely follow-up at the acute phase provides an opportunity to assess patient response and adjust treatment plans, potentially influencing the trajectory of treatment and patient outcomes. As shown in a previous study of between-site variation in a large CCM demonstration project (

32), sites with higher rates of early follow-ups also had better patient depression outcomes that were not explained by patient characteristics. Second, early-stage follow-up enables care managers to conduct patient education and strengthen clinical alliances at a time when patients are at a high risk of becoming nonadherent to antidepressant therapy (

45). Third, care manager contact may have therapeutic effects independent of its support of antidepressant or psychotherapy interventions. As seen in several large trials of the CCM, the effect of the intervention on depression outcomes was found as early as three months after the start of the program (

35,

46), suggesting that increased clinician attention and patient engagement in the early phase of CCM may have had a direct effect before improved antidepressant treatment or psychotherapy could translate into improved patient outcomes.

Our findings also support the value of timely psychiatric consultation when patients do not experience improvement in the early phase of CCM. Patients who did not achieve improvement in the first eight weeks were likely more clinically challenging to treat, as indicated by their substantially lower rate of improvement within six months (about 20%) compared with rates for the entire cohort (30%−40%). Our results suggest that timely psychiatric consultation to adjust treatment could substantially improve the chances of remission and recovery for patients whose depression is resistant to initial treatment. On the other hand, psychiatric consultation did not predict more speedy improvement. Reasons might be the low rate of improvement (about 20%) in this cohort and the fact that it took a much longer time for the majority of this cohort to achieve improvement (around 48 weeks) [see online supplement].

Our findings should not be interpreted to indicate that the two CCM tasks studied were the only tasks primary care teams need to practice to achieve improved patient outcomes. Primary care practices need to first undertake the systematic and organizational changes necessary to implement the CCM (

27,

47). These include both changes in overall approaches to chronic care (for example, addition of a care manager to perform care management activities outside of primary care visits) and infrastructure building to enable operation (for example, the use of a depression registry). In this study, we chose to focus on process-of-care measures because they are less studied and are likely subject to greater variation in implementation.

By design, different process-of-care tasks of CCM are often practiced together and enable each other. For example, using PHQ-9 to continuously assess patient outcomes (

Table 1), a key task of CCM that was not studied here, is an important part of each care manager contact with the patient and provides the basis for psychiatric consultation. This study provides evidence to support two key tasks in the first four to 12 weeks of CCM, without negating the importance of the other key tasks of CCM identified by expert consensus (

Table 1).

Several limitations should be noted. First, despite propensity score–adjusted analysis, unobserved and unmeasured differences between patients who received either task and those who did not might be substantial and might have led to biases in our estimates. As discussed above, selection by patient baseline severity and complexity could have biased our estimates toward the null. Selection could also have occurred through patient motivation: patients with greater motivation were more likely to follow through with care management appointments but, at the same time, all else being equal, were more likely to achieve improvement in depression. Thus selection by motivation could have biased the effect of the four-week follow-up away from the null (that is, toward suggesting a positive effect of follow-up), offsetting the selection bias by severity to an unknown extent.

Second, practice of either task may reflect the overall quality or fidelity to CCM at a given implementation site. This concern, however, was alleviated because our adjusted analysis controlled for all time-invariant, between-site differences by inclusion of site fixed effects. Results of our analysis thus reflect how variation in task performance (either over time or across patients) within a given site predicted patient outcomes. Nonetheless, the practice of either task may be correlated with the practice of other related tasks for the same patient. For example, timely follow-up in the early phase may increase the likelihood that patients are continuously engaged and followed up in the rest of the treatment episode. Thus estimated ORs and hazard ratios associated with either of the two tasks may reflect a combination of their direct effects and indirect effects mediated through other tasks and need to be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Our study provided strong evidence that timely care manager follow-up in the first four weeks of CCM predicted substantial improvement in patient depression outcomes. Evidence regarding timely psychiatric consultation for cases in which patients did not respond to the initial course of treatment was less consistent but suggestive of the benefits of this task. Our findings support efforts to improve fidelity to these two process-of-care tasks and to include these two tasks among quality measures for CCM implementation. Future studies should seek to assess the relative importance of other key tasks of CCM and test implementation strategies (for example, pay for performance) to encourage and enable high fidelity to tasks found to contribute to good patient outcomes.