Approximately one-quarter of adults with serious mental illness are involved with the criminal justice system (

1). Although the causes of offending in this diverse population are complex, they likely fall along a spectrum of influences: features of psychopathology, propensity for offending that is not directly related to mental illness, substance abuse, and a range of social-environmental factors that are shared by offenders without mental illness (

2). Among adults with serious mental illness, there is also a wide range of involvement in public treatment and criminal justice systems and associated costs because their treatment needs (

3), service utilization (

4), and risk of offending (

5) vary significantly.

A recent study characterized the landscape of criminal justice involvement, treatment utilization, and associated costs for a population of adult clients of a state behavioral health system (

1). Here we extend this work by examining the direct influence of justice involvement—as well as its interplay with key clinical characteristics—on community behavioral health treatment costs. The results provide early insights about the extent to which behavioral health treatment costs for this population are driven by system characteristics, justice involvement, and individual illness trajectories.

Data and Procedures

Administrative records from public behavioral health and criminal justice agencies in Connecticut were merged for 25,133 adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who were clients of the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS) during state fiscal years 2006 and 2007. Data for treatment services provided in the community included Medicaid claims for psychiatric hospitalizations, outpatient services, and psychotropic medications; and DMHAS records for state psychiatric hospitalizations, including forensic hospitalizations and a range of outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment. Criminal justice records included arrests, incarceration, parole, probation, jail diversion program participation, evaluations for competency to stand trial, and records for individuals found not guilty by reason of insanity. Costs from Medicaid-paid services were collected directly from claims records. Unit costs were estimated for all DMHAS services with inflation adjustment to 2007 dollars. Details about the data sources, sample, and cost estimates are available in the related cost study (

1).

Ordinary least-squares regression models examined the net effect of justice involvement and, separately, the combined effects of justice involvement and clinical diagnoses on behavioral health treatment costs. Specification tests were first conducted to determine the best model fit. Two sets of risk factor combinations represented, first, combinations of justice involvement status and substance use disorder diagnosis and, second, justice involvement and major psychiatric diagnosis (schizophrenia or bipolar disorder). All models controlled for age, sex, race-ethnicity, and time out of the community during incarceration.

Findings

Approximately 27% of the sample was justice involved at some time during the two-year study period. Among those with justice involvement, 37% had schizophrenia and 63% had bipolar disorder. The mean±SD age of those with justice involvement was 35.7±10.5, 65% were male, and 65% had a diagnosed co-occurring substance use disorder. Among the 73% without justice involvement, 53% had schizophrenia, 47% had bipolar disorder, the mean age was 43.5±13.8, 46% were male, and only 28% had a co-occurring substance use disorder.

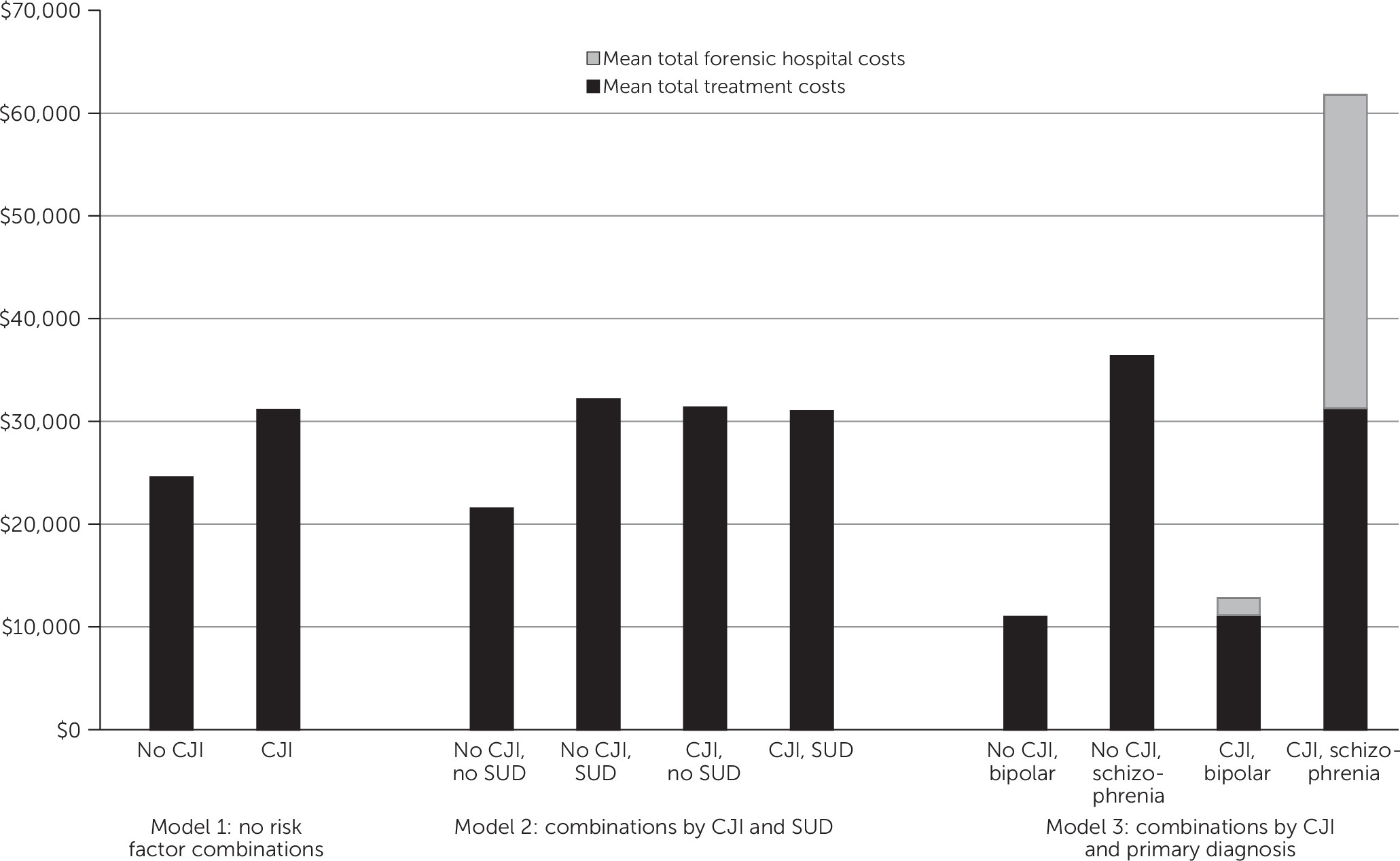

In the model that controlled only for gender, age, and race-ethnicity, treatment costs were nearly 27% higher for those with justice involvement compared with those who had no justice involvement ($31,166 versus $24,602) (

Figure 1, model 1). Having a co-occurring substance use disorder increased treatment costs by nearly 50% among those with no justice involvement, but a co-occurring substance use disorder had virtually no effect among those who were justice involved (model 2).

Most notably, primary psychiatric diagnosis had the largest influence on treatment costs, particularly among those who were justice involved (model 3). Total predicted treatment costs for justice-involved adults with schizophrenia ($61,824) were nearly 70% higher than the costs for adults with schizophrenia and no justice involvement ($36,408). Costs for justice-involved adults with schizophrenia were nearly five times higher than costs for justice-involved adults with bipolar disorder ($61,824 versus $12,864). Among those without justice involvement, costs among adults with schizophrenia were 3.3 times higher than among their counterparts with bipolar disorder ($36,408 versus $11,039).

A key driver of higher costs among justice-involved adults with schizophrenia was the disproportionately high cost of forensic hospitalizations, which are justice-connected in context but which are provided and paid for by DMHAS. Forensic hospitalizations accounted for nearly half of that group’s total treatment costs and contributed to their costs being 70% higher than costs for adults with schizophrenia who had no justice involvement. Among the justice-involved adults, forensic hospitalization was far more common for those with schizophrenia than for those with bipolar disorder. Ten percent of the justice-involved adults with schizophrenia had at least one forensic hospitalization, with a cumulative mean of 265±269 hospital days during the two-year period, whereas only 1% of the justice-involved adults with bipolar disorder had a forensic hospitalization, with a cumulative mean of just 151±210 days (data not shown). Forensic hospital costs for the justice-involved adults with schizophrenia were 18 times higher than for those with bipolar disorder ($30,528 versus $1,694). [Results of regression analyses described in this section are available in an online data supplement to this column.]

Implications

The combination of justice involvement and a co-occurring substance use disorder did not have a strong influence on behavioral health treatment costs. In fact, among the justice-involved adults in this sample, treatment costs for those with a substance use disorder were nearly the same as for those without. The justice-involved adults with a co-occurring substance use disorder may have been receiving the same amount of treatment as their counterparts with mental illness alone, but it was integrated care for co-occurring disorders. Another possible explanation is that the justice-involved adults with a co-occurring disorder did not use sufficient treatment, especially if most mental health and substance use treatment was undertaken separately.

Instead, primary psychiatric diagnosis in combination with justice involvement had a marked influence on treatment costs, especially among justice-involved adults with schizophrenia. A large part of that group’s high costs was driven by their disproportionate use of forensic hospitalizations (with longer stays than nonforensic hospitalizations), most commonly for having been found incompetent to stand trial but also for having been found not guilty by reason of insanity, or for other forensic evaluations performed for an offender’s trial that were not related to competency.

Individuals with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are at higher risk than those with mood disorders of incompetency findings (

6), less likely to be restored to competency once found incompetent (

7), and undergo longer related forensic hospitalizations (

7,

8), which is highly consistent with the forensic hospitalization experience among the adults in our study.

Competency evaluations for criminal defendants have been described as a “back door” into psychiatric hospitals for individuals with serious mental illness who need inpatient care but are not committable under psychiatric-need criteria alone, and an estimated 50% of public hospital beds are occupied by forensic patients. In that way, the distributions of treatment costs in this sample represent a story of individuals’ movement through the public treatment and criminal justice systems and the way in which that system involvement differentially links them to treatment. Important differences in costs between the adults in this population with and without justice involvement are also to some extent a story of the life course of mental illness, including generally higher degrees of disability and use of high-cost care among persons with schizophrenia (

3,

4).

These results demonstrate important patterns in one state’s behavioral health treatment costs for adults with serious mental illness that warrant further examination—namely, the marked combined effect of primary psychiatric diagnosis and justice involvement on treatment costs. A closer focus on how the public treatment and justice systems may need to coordinate to reduce risk and costs for justice-involved adults with schizophrenia, including possible alternatives to high-cost, often lengthy forensic hospitalizations, such as outpatient programs for competency restoration, may be a sensible place to start.