Substance use disorders are a growing public health concern in the United States. In 2012, a reported 23.1 million Americans needed treatment for a substance use disorder, including both illicit drug and alcohol use disorders (

1). Moreover, the number of persons who are dependent on or who abuse opioids approximately doubled over the past decade (

2), and this surge in opioid use disorders was associated with high mortality rates, particularly deaths from overdose (

2–

4). Although the number of Americans with alcohol use disorders has not increased significantly in the past decade, alcohol remains the third leading actual cause of death in the United States (

5). However, the percentage of Americans with substance use disorders receiving treatment for their condition remains consistently low. Only 10% of persons in need of treatment receive care in a given year (

6).

Substance Use Disorder Medications

Over the past three decades, researchers have developed several medications to treat substance use disorders, including naltrexone, buprenorphine, and acamprosate. These medications join disulfiram and methadone, which have been used to treat substance use disorders for over 50 years. The efficacy of these medications is well established (

7–

14), and research evidence shows that when used in conjunction with behavioral therapy, medications are associated with reductions in heavy drinking, number of drinking days, opioid use, and opioid withdrawal symptoms as well as with increased treatment retention (

8,

9,

15–

19). Receipt of naltrexone for opiate and alcohol use disorders is associated with significant declines in health care utilization and overall health care costs (

20–

22).

Current treatment guidelines suggest that all persons diagnosed as having substance use disorders be assessed for treatment with a medication (

23–

26). However, only a small percentage of persons with substance use disorders receive a medication as part of their treatment regimen, and a majority of treatment programs do not offer medications (

27). Among treatment programs that offer medications, cost can be a barrier to patient receipt. Many clients lack insurance coverage that covers the costs of medications, which can be prohibitively expensive (

27–

30).

Insurance Enrollment and Substance Use Disorder Medications

Prior research examining the availability of medications in treatment programs explains the adoption of medications almost exclusively as a function of the internal characteristics of treatment programs (

27,

28,

31–

35). In terms of organizational structure, programs located in hospital settings (

27,

31), accredited programs (

28,

36), programs that are larger in size (

31,

37–

39), government-owned programs (

27,

28,

39,

40), for-profit programs (

36,

41), and programs that offer outpatient-only treatment services (

27) are more likely than other programs to adopt medications. Staff education, measured by the percentage of counselors with a master’s degree or higher, is positively associated with availability of medications (

27,

40,

42). Treatment programs with a higher percentage of patients covered by private insurance or a higher percentage of annual revenues from private insurance are more likely to offer medications (

27,

28,

31,

37,

43).

Despite studies showing that treatment programs which offer medications are more heavily reliant on insured clients, research has not considered the potential effects of the broader health insurance context on treatment programs’ decisions to offer medications. In the general health care literature, several studies have found that the broader “marketplace” in which health care providers operate has a significant impact on their decisions regarding the services and products they offer. In particular, these studies indicate that health service providers located in communities with higher rates of health insurance enrollment are more likely to provide a wide range of health care products and services (

44–

47). These findings suggest that low prevalence of insurance enrollment may inhibit a community’s demand for services, which may in turn discourage health service providers from making the investments necessary to procure new health care services and products. Given that the vast majority of state Medicaid programs and private health insurance programs now cover one or more medications for substance use disorders, the extent of insurance enrollment within state and local markets may have a significant impact on treatment programs’ decisions to offer medications.

Understanding this relationship is particularly relevant given the passage and implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) (

48,

49). First, the ACA has increased the number of insured Americans through optional expansion of Medicaid and the creation of state and federal health insurance marketplaces. To date, 16.9 million previously uninsured Americans have gained access to health insurance through Medicaid expansion and the ACA marketplaces (

50). Second, the ACA mandates that the essential health benefit (EHB) package of both Medicaid expansion and health insurance marketplace plans provide coverage for substance use disorder treatment, including prescription drugs (

48).

Third, the ACA expands the reach of existing parity rules established by the MHPAEA, which require health plans that elect to cover substance use disorder treatment to do so in a manner that is no more restrictive than the manner by which they cover other medical and surgical procedures (for example, by using comparable deductibles, copays, coinsurance, and treatment limitations). Prior to the implementation of the 2014 provisions of the ACA, only private group health insurance plans and Medicaid managed care group health plans with more than 50 employees were subject to MHPAEA requirements. Now, Medicaid EHB packages and all plans in the marketplaces must comply with parity requirements.

Given these dramatic increases in health insurance enrollment and the potential impact of these insurance expansions on substance use disorder treatment, it is important to examine the impact of health insurance enrollment on the availability of medications within treatment programs. The primary objective of the study was to examine the relationship of state prevalence of health insurance enrollment to availability of medications for the treatment of substance use disorders among the population of treatment programs in the United States.

Methods

In this study, we combined four publicly available sources of data: the 2012 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS), the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau), the Area Health Resource File (AHRF), as well as data on Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment (SAPT) block grant funding (

51). N-SSATS is an annual census of all known facilities in the United States providing substance use disorder services sponsored by SAMHSA. N-SSATS is the only national data set of treatment programs that includes treatment programs in every state (

52). In this study, treatment programs that provided DUI-only services and solo practices were excluded from analyses, resulting in a final sample of 9,888 treatment programs.

We included state estimates of substance use disorder prevalence from the 2012 NSDUH (

1). NSDUH is an annual survey of the general U.S. civilian population. It includes data annually from approximately 70,000 Americans ages 12 and older in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Survey respondents are identified by using a state-based design with an independent, multistage area probability sample within each state and the District of Columbia.

The U.S. Census Bureau provided estimates of state population, state per capita income, and health insurance enrollment per state in 2012 (

53). The study included a measure created from the 2012 AHRF of the number of physicians per 100 persons living in the state (

54) and a measure from the SAMHSA Web site of SAPT block grant award amounts (2011–2012) for each state (

51). All data were collected prior to the implementation of Medicaid expansion and state health insurance Marketplaces under the ACA.

Measures

Dependent variable.

Treatment programs were coded as 1 if they offered any of the following medications for the treatment of substance use disorders: disulfiram, oral naltrexone, injectable naltrexone, acamprosate, buprenorphine, or methadone. Programs that did not prescribe any medications were the reference group.

Independent variables.

Consistent with prior research, we controlled for several internal characteristics of treatment programs related to availability of medications in prior research (

27,

28,

31,

40,

43). Location (hospital setting or freestanding [reference]), profit status (private for profit or nonprofit or government owned [reference]), and accreditation (accredited or not accredited by the Joint Commission/CARF [reference]) were dichotomous variables. Treatment program size was measured by the total number of admissions in the past year; this variable was log transformed to adjust for skewness. Service mix was measured by using a dichotomous variable denoting whether the treatment program solely provides outpatient services (outpatient only or residential services only or a mix of residential and outpatient services [reference]). We included two dichotomous variables indicating whether each treatment program accepts or does not accept (reference) private insurance and accepts or does not accept (reference) Medicaid insurance.

To determine whether substance use disorder prevalence was associated with availability of medications, we included two continuous measures: the percentage of the state population that was dependent on an illicit drug in the past year and the percentage of the state population that was dependent on alcohol in the past year. We measured the prevalence of health insurance enrollment in 2012 by using three continuous variables taken from the U.S. Census Bureau: the percentage of the state population that reported having employer-based insurance, the percentage of the state population that reported having nonemployer-based private insurance, and the percentage of the state population that reported having Medicaid. We also controlled for the percentage of the state population that was uninsured. We created a measure of physician accessibility by using data from the 2012 AHRF to calculate the number of physicians per 100 persons living in each state. We also controlled for state population (log transformed), state per capita income (log transformed), and total SAPT block grant program funding per capita for each state.

Analytic Technique

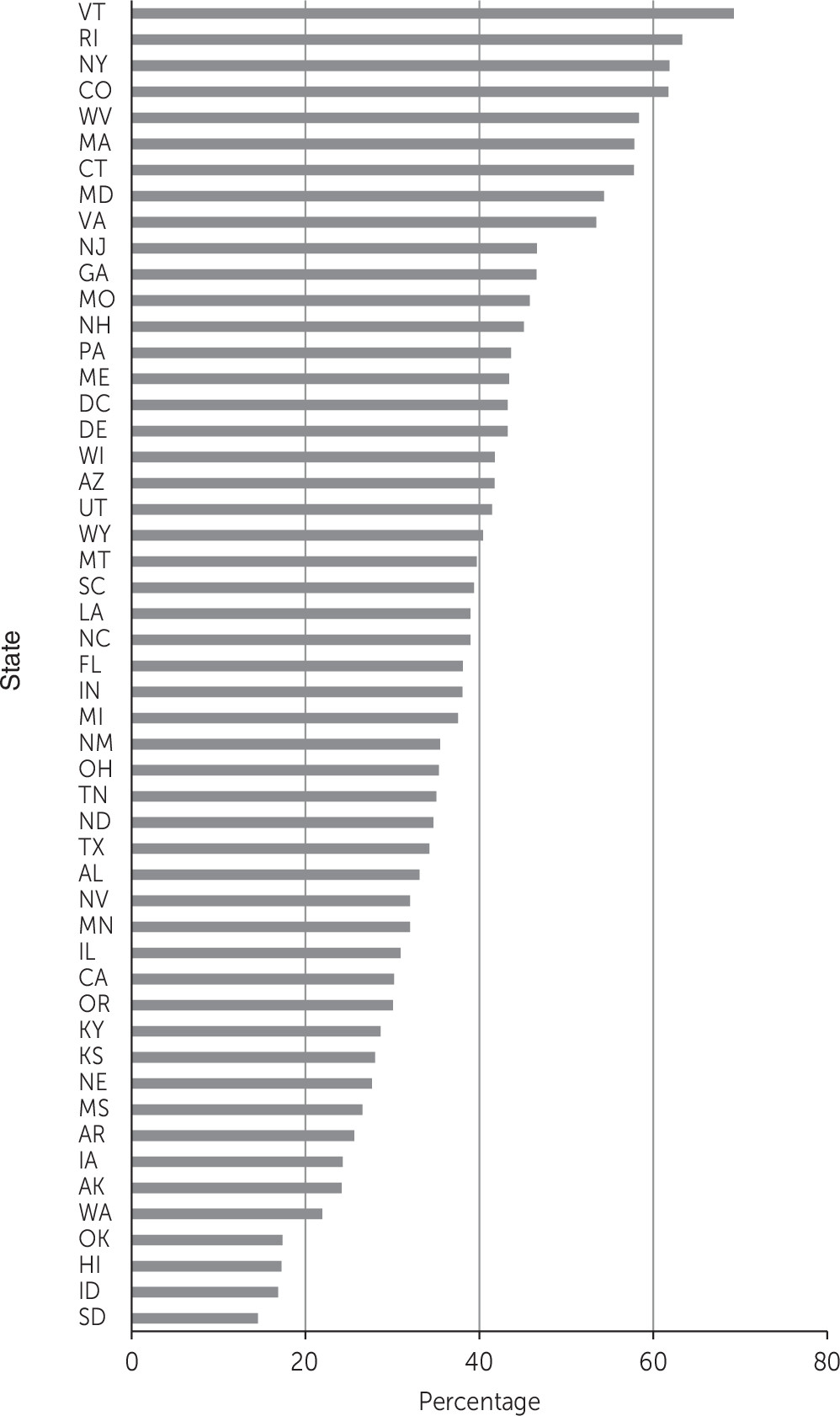

We calculated descriptive statistics for all variables. To show variation in availability of medications by state, we first graphed the proportion of treatment programs in each state that provided at least one medication. We examined data for multicollinearity, and the checks revealed no evidence of multicollinearity. We used a two-level, random-intercept logistic regression model to account for potential unobserved heterogeneity among treatment programs nested in states. We calculated predicted probabilities of offering a medication corresponding with a 5% increase in the state population covered by employer-based insurance and Medicaid insurance. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 13.0 (

55).

Results

Figure 1 displays the proportion of treatment programs in each state offering at least one medication for the treatment of substance use disorders. As expected, there was wide variation by state in the percentage of programs offering at least one medication, ranging from 14.5% in South Dakota to 69.2% in Vermont (mean=38.6%).

Descriptive statistics for treatment program– and state-level variables are presented in

Table 1, and results of two-level logistic regression models are presented in

Table 2. The odds of offering at least one medication for the treatment of substance use disorders were greater for treatment programs in states that had a higher per capita income (odds ratio [OR]=1.09). Treatment programs located in states with higher prevalence of alcohol dependence were less likely to offer medications (OR=.59), and programs in states with higher prevalence of illicit drug dependence were more likely to offer medications (OR=3.75). Consistent with prior research, the odds of offering at least one medication were greater for hospital-based treatment programs (OR=3.20), for-profit treatment programs (OR=2.27), accredited programs (OR=4.09), and programs that were larger in size (OR=1.36). The odds of offering medications were lower for programs that offered outpatient-only treatment services (OR=.74). Programs that reported accepting private insurance (OR=1.25) and Medicaid insurance (OR=1.29) were also more likely to offer at least one substance use disorder medication.

The odds of offering at least one medication for the treatment of substance use disorders were greater in substance use disorder treatment programs located in states with higher percentages of the population covered by employer-based insurance (OR=1.08) and Medicaid insurance (OR=1.10). Every additional 5.0% of the state population covered by employer-based insurance translated to a 7.7% increase in the probability of offering at least one of the medications (marginal effect=.48, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.39–.57). Every additional 5.0% increase in the percentage of the state population covered by Medicaid translated to a 9.3% increase in the probability of offering at least one of the medications (marginal effect=.49, CI=.40–.59).

To demonstrate the differential effects of state insurance enrollment on availability of medications by state, we calculated the predicted probability of offering medications in South Dakota and Idaho, the states with the lowest percentage of programs offering medications. The predicted probability of offering medications in South Dakota and Idaho was .21 and .24, respectively. By setting the percentage of the state population covered by employer-based insurance to the highest value observed in the data (58.9%), the predicted probability of offering a medication increased to .35 (CI=.18–.53) in South Dakota and to .42 (CI=.20–.64) in Idaho. We then set the percentage of the state population covered by Medicaid to the highest value observed in the data (25.4%). The predicted probability of offering a medication increased to .39 (CI=.17–.61) in South Dakota and to .45 (CI=.20–.70) in Idaho.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the relationship between extent of health insurance enrollment and the availability of medications within treatment programs in each state. We found wide variation in the availability of medications by state. This finding suggests that in many states, persons with substance use disorders lack adequate access to medications. In fact, the proportion of treatment programs offering at least one medication was greater than 50% in only nine states, located primarily in the Northeast.

We found that the rate of health insurance enrollment was consistently and positively linked to the availability of medications for substance use disorder treatment. Specifically, treatment programs in states in which a higher percentage of the population was covered by employer-based health insurance were more likely to offer at least one medication. Consistent with our prior research, we also found that treatment programs that accept private insurance were more likely to offer medications (

27,

28,

31,

37,

43).

Similarly, the percentage of the state population covered by Medicaid insurance was positively associated with availability of medications. This finding is supported by prior research that found that treatment programs in states that covered buprenorphine under the state Medicaid plan were more likely to adopt the medication, as were programs located in states that made state funds available to subsidize buprenorphine (

43,

56). Overall, we found that treatment programs were more sensitive to changes in rates of state Medicaid enrollment compared with rates of private insurance. This may be due to the fact that a large proportion of people who receive substance use disorder treatment have low incomes (

6). Medicaid enrollment may be an especially important driver of medication availability among safety-net providers who primarily serve low-income populations. Although employer-based health insurance programs typically offer more generous coverage for medications, enrollment in such programs may have a weaker influence on substance use disorder medication availability because clients with employer-based insurance make up a smaller proportion of the typical treatment program’s revenue base (

57).

Our results suggest that insurance expansions initiated by the ACA (Medicaid expansion, establishment of state and federal health marketplaces, and ACA’s enhancement of parity legislation) may increase the availability of medications for treatment of substance use disorders. Access to medications may be especially important in states that expand Medicaid because the rate of substance use disorders among new enrollees, estimated to be approximately 15%, is much greater compared with rates in the general population (

58). With Medicaid now projected to become the largest payer of substance use disorder treatment services, more treatment programs may be likely to accept Medicaid.

Our findings suggest that access to medications for the treatment of alcohol use disorders is not consistent with treatment need in many states. However, at the same time, treatment programs in many states are responding to the need of patients with opioid use disorders. This finding is promising given the recent increases in opioid use disorders and deaths from overdose associated with heroin and prescription opioid abuse. Consistent with prior research, we found that per capita spending on substance abuse prevention and treatment was not associated with availability of medications (

59). Thus, one strategy to increase availability of medications is for single state agencies to increase the amount of funding allocated to facilitate adoption and implementation of medications. Other strategies to facilitate adoption of medications include seeking greater integration with mainstream health care, increasing availability of addiction training for physicians, and increasing the buprenorphine patient limit for waivered physicians.

Several limitations of the study are noteworthy. First, N-SSATS does not include measures of staff education and training, which have been shown in prior research to influence organizational adoption of medications. Second, N-SSATS includes only a dichotomous measure of whether programs accept various types of health insurance and does not provide information regarding what percentage of patients are covered by a particular type of insurance. Thus we were unable to determine whether the impact of state insurance enrollment on availability of medications varied on the basis of percentage of patients in each program who were covered by private insurance and Medicaid. In addition, our study did not account for variability in the quality and comprehensiveness of health insurance coverage offered across various plans. Third, the study was cross-sectional, and, consequently, we are unable to draw causal inferences from our findings.