Introduction invited by the column editor: Evidence for the advantages of clozapine for some patients has been available for more than a decade. Patients who could benefit from clozapine disproportionately receive care in the public sector. However, public-sector prescribers have been hesitant to use clozapine because it has immediate life-threatening side effects for a small percentage of patients. Clozapine also has life-shortening side effects, such as weight gain, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, that require long-term intervention with agents that prescribers in the public mental health system may not be familiar with or are uncomfortable using—and collaborative primary care is not consistently available in public mental health settings. Prescribers’ hesitancy is understandable. However, we would be horrified if oncologists avoided using chemotherapy because the agents had life-threatening side effects and because knowledge and skill are necessary to prescribe them appropriately. This column shows that the approach taken in New York—combining assistance to public-sector prescribers with clear directives for appropriate clozapine use—has been successful. We have too long valued the comfort of prescribers over the well-being of patients with severe mental illness. It is time for prescribers to step up, and we should assist them.—Joseph P. McEvoy, M.D., Georgia Regents University, Augusta

Nearly three decades after its approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), clozapine remains the only medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. No other antipsychotic or combination of antipsychotic medications is as effective as clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Despite its well-established superior efficacy, delays and underuse of clozapine continue to be the norm nationally and internationally. Treatment guidelines recommend consideration of clozapine for individuals for whom two prior antipsychotic trials have failed. Yet survey data suggest that delays in clozapine prescribing range from five to ten years, with prescribers often resorting to practices unsupported by evidence (

1).

An investigation that examined clozapine use in 2009 for Medicaid recipients in New York with a diagnosis of schizophrenia found that clozapine accounted for only 2% of new antipsychotic starts (

2). A subsequent national study found that patterns of clozapine use in the rest of the United States resembled the modest usage in New York (

3). Although estimates vary depending on study criteria, it is generally accepted that approximately a third of individuals with a schizophrenia diagnosis who have had two or more antipsychotic trials had less than adequate responses to those trials. However, the percentage of individuals with schizophrenia who have had a trial of clozapine falls far short of this. The national study found significant variation in prescribing at the state and county levels, suggesting that local practice patterns significantly influence clozapine use (

3). Local patterns were more strongly associated with clozapine use than several clinical factors, such as frequent medication changes and high levels of mental health service use.

Many reasons for clozapine underuse are cited: insufficient prescriber training; clinical concern over rare but serious medical risks, including agranulocytosis and myocarditis; frequent blood draws for granulocyte monitoring; relatively high administrative burden; and troublesome side effects, including weight gain, sedation, and drooling (

4). Moreover, clozapine’s visibility has decreased because generic forms have been available for many years, and pharmaceutical company efforts to market it have largely ceased.

The New York State Initiative

Considering the low rates of clozapine use in New York, the medical director of the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYS OMH) introduced the “Best Practices Initiative—Clozapine” in 2010 to promote its evidence-based use in state-operated facilities. To enhance clozapine access among individuals who stand to gain the most, the initiative targets both perceived “supply side” and “demand side” barriers; it provides a host of supports for prescribers and a decision aid tool for consumers grounded in the principles of shared decision making. With adequate supports for consumers and prescribers, the expectation was that clozapine could play an important role in individual recovery plans.

Although definitions of treatment-resistant schizophrenia vary, the initiative adopted a broad interpretation that included adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders whose illness materially impeded their recovery—for example, prevented them from attending school, developing and maintaining supportive social relationships, or acquiring employment—despite two antipsychotic trials.

The initiative engaged academic partners at Columbia University Medical Center, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York University, and the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research as well as clinical leaders from NYS OMH state-operated psychiatric centers (PCs). Led by the medical director’s office, these collaborators developed a manual for clinicians and made a series of statewide grand rounds presentations. Several senior psychiatrists agreed to participate in a telephone consultation service, receiving clozapine-related calls from any NYS OMH prescriber (staff psychiatrists and nurse practitioners) on weekdays during business hours.

In 2011, the medical director’s office began tracking clozapine prescribing at the 16 adult state-operated PCs, focusing primarily on the 66 outpatient clinics within those care systems that represent approximately 20% of all adult outpatient clinics in the state’s public mental health system. These 16 PCs employ nearly 400 psychiatrists and 50 nurse practitioners and serve approximately 27,000 individuals with serious mental illness each year, most of whom have a diagnosis of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Detailed action plans were required from centers with low levels of clozapine use. NYS OMH provided clinical directors with quarterly feedback on progress by means of a report showing clozapine use trends over time for each PC and comparisons among the 16 PCs.

NYS OMH partnered with the Center for Practice Innovation at the New York State Psychiatric Institute to create interactive Internet-based educational programs to provide information about clozapine to consumers, family members, and clinicians. The first program, “Considering Clozapine,” is a publicly available Web-based module that provides information for consumers and family members about clozapine, including benefits and risks. A key component is a series of testimonials from consumers, who describe personal benefits from clozapine along with its challenges. The second Internet-based educational program, “Motivating Clozapine Use,” is directed at clinicians. It includes testimonials from consumers and family members and provides tips for presenting clozapine as an option to patients in a balanced way consistent with principles of shared decision making.

Program Evaluation

Below we describe an evaluation of the initiative—a retrospective longitudinal study (2009–2013) of patterns of new antipsychotic starts for individuals identified by Medicaid data as having schizophrenia (N=42,310). New starts of antipsychotics (N=115,320) were defined as an outpatient filled prescription immediately preceded by 90 or more days during which no prescription for the same antipsychotic was filled. The percentage of clozapine new starts among all new antipsychotic trials increased from 1.5% (2009) to 2.1% (2013).

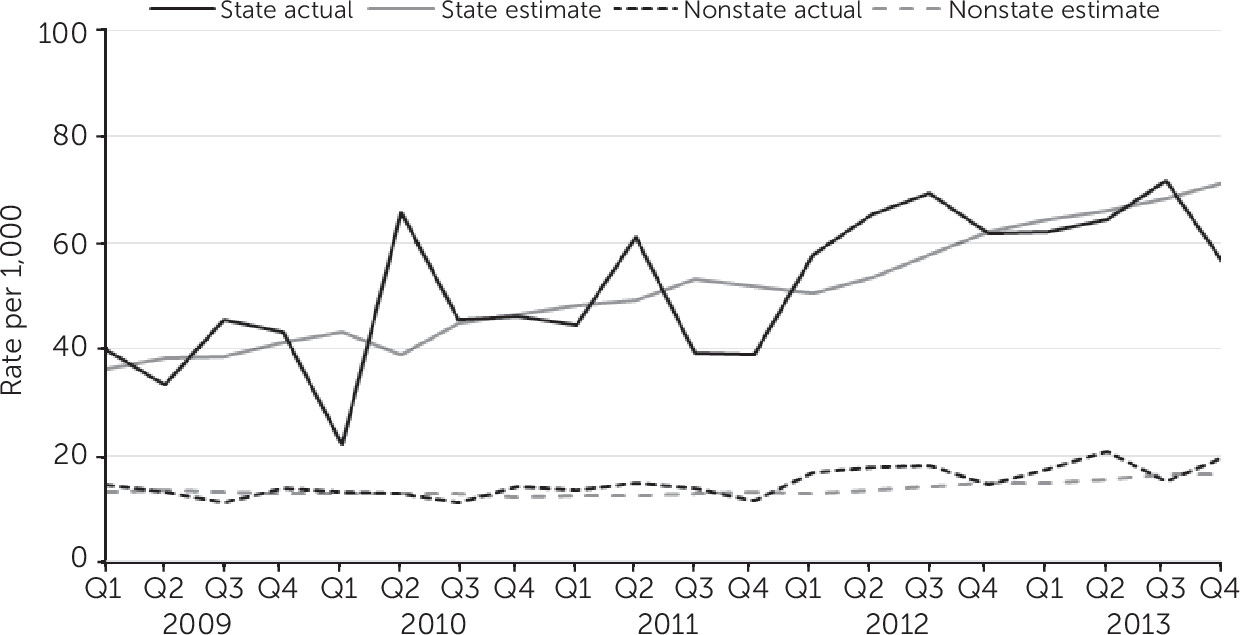

Individuals who received services from state-operated facilities at any point during the study were compared with all others (those receiving non–state-operated services). A total of 2,768 individuals were served in state-operated settings and accounted for 7,551 new antipsychotic starts. The rate of clozapine new starts per quarter also increased when compared with all new antipsychotic starts (

Figure 1), with the greatest change seen at state-operated facilities. The average quarterly percentage change in the rate of clozapine new starts in these facilities was more than three times that in other settings (3.77% compared with 1.13% in other settings).

Discussion

More than 25 years after its FDA approval for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, clozapine remains the only antipsychotic approved for this indication. However, its low use remains the quintessential science-to-service gap in behavioral health services. The NYS OMH experience suggests that clozapine prescribing can be positively influenced by a commitment to quality improvement, strategic public-private partnerships, and provision of supports for prescribers and consumers. Sustained support from NYS OMH leadership led to a 40% increase in clozapine new starts among the Medicaid cohort and a doubling in the estimated rate of new clozapine prescriptions at state-operated facilities (an increase of 36 to 71 per 1,000 new starts). These changes were achieved in settings where prescribers had already completed postgraduate training—that is, when practice patterns may be relatively inelastic. Furthermore, increasing clozapine uptake occurred for a generic medication in the absence of a well-funded pharmaceutical marketing campaign.

How can we build on the progress in New York and broaden access to clozapine? With the FDA’s recent announcement allowing more individuals (such as those with benign ethnic neutropenia) to receive clozapine, the United States joins other nations that have had similar policies for years. Advances in point-of-care granulocyte testing may also offer improved clozapine access by making blood monitoring more convenient for consumers. Furthermore, the focus on integrated care, care coordination, and increased use of decision support tools in electronic medical records may provide a more favorable infrastructure for systematic clozapine use. In the United States, payers and managed care organizations could adopt policies that incentivize earlier access to clozapine. Training in clozapine use during psychiatric residency is another important opportunity to broaden access.

A multicomponent initiative to improve clozapine prescribing in NYS led to an increase of new clozapine starts. Further increases will require sustained efforts to identify patients likely to benefit from clozapine, minimize demand- and supply-side barriers, and develop a workforce skilled in its use. Until more effective medications become available for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, improving safe access to clozapine must be a priority.