Premature treatment dropout and poor medication compliance are common challenges in treating people with mental disorders (

1–

4). Less than two-thirds of veterans with prescriptions for psychiatric medications for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) refill their medications for three or four months, as recommended in practice guidelines (

4–

6). Only 64% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who initiate psychotherapy complete a full course of treatment (

7). Other studies have shown that only 25% to 35% of U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients receiving psychotherapy for PTSD complete eight or more sessions (

4,

8).

Several factors may limit engagement in PTSD treatments (

9). Veterans may doubt whether psychotherapy and medications are effective (

10–

13). People may delay psychotherapy to avoid talking about traumatic events (

14,

15). PTSD-related alienation and distrust might interfere with developing a strong therapeutic alliance (

16,

17). Scheduling difficulties and travel distances can be barriers to care (

12,

18,

19). Some studies have shown that compared with Vietnam veterans, veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts complete fewer PTSD treatment visits, perhaps because of less mental health treatment experience (

8,

9), lower readiness for change, different comorbid conditions, greater confidentiality concerns, or competing time demands (

18,

20–

23).

Care management programs that include telephone support can improve treatment engagement and outcomes for depression or alcohol problems managed in primary care (

24,

25). Brief motivational interventions via telephone can improve acceptance of mental health referrals (

26,

27). Telephone support can also reduce relapse after addiction treatment (

28).

There has been less research on using telephone support to aid PTSD treatment retention. Two trials of care management that included a telephone care component with veterans recruited from primary care showed mixed results. One study found that care management improved attendance but not outcomes (

29). Another study found that a combination of evidence-based psychotherapy via video teleconferencing and care management significantly improved both treatment attendance and outcomes (

30). A trial with veterans being discharged from residential PTSD treatment found that telephone support had no effect on either aftercare attendance or outcomes, given that nearly all of these patients were already participating in aftercare (

31). No prior trials have tested a care management intervention to improve attendance and outcomes of PTSD patients in mental health clinics, although premature treatment dropout is common in these settings (

8,

21).

Study Hypotheses

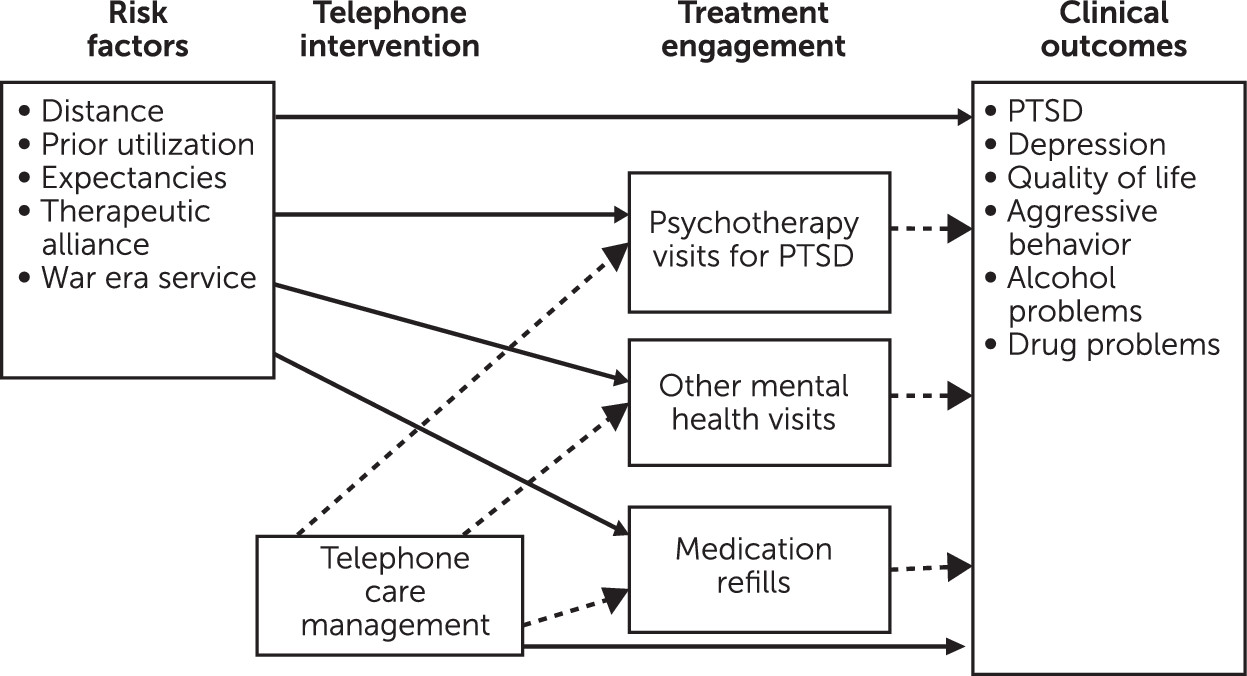

The goal of this study was to test whether telephone care management (TCM) increases treatment adherence of veterans initiating a new phase of outpatient mental health specialty treatment for PTSD (

Figure 1). Our primary hypothesis was that compared with patients receiving only usual care, those randomly assigned to usual care plus three months of TCM would attend more mental health appointments during the three-month intervention period and during the nine-month follow-up period and would have higher medication possession ratios (MPRs) over the 12-month study period, indicating more prescription refills for prazosin and for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Our second hypothesis was that patients assigned to the TCM condition would show greater reductions in PTSD and depression symptoms over 12 months than would those receiving usual care. Moreover, the effects of TCM on PTSD and depression would be mediated by patients attending more mental health appointments and having higher MPRs. Our tertiary hypotheses were that patients in the TCM condition would have greater improvements in aggressive behavior, alcohol misuse, drug use, and quality of life than those receiving usual care.

Additional exploratory analyses examined whether risk factors for poor treatment engagement moderated the effects of TCM on treatment attendance and medication refills. We hypothesized that the effects of TCM relative to usual care would be strongest among patients who participated in less mental health treatment in the year before the study (

8), lived farther from the nearest VA clinic (

12), served in Iraq or Afghanistan (

12,

23), had poorer therapeutic alliance with their clinician (

17), or had lower expectations that mental health treatment would resolve their presenting problems (

11,

12).

Methods

Participants

A total of 1,346 veterans were assessed for eligibility between March 2009 and April 2013 from outpatient mental health programs at three VA medical centers. These included three PTSD specialty clinics, one Iraq-Afghanistan veteran clinic, and one general mental health clinic. Veterans were eligible to participate if they were newly entering outpatient PTSD treatment or were beginning a new phase of treatment (such as transitioning from a psychoeducation group to other psychotherapy). Participants were recruited before their third session of the new treatment. A total of 190 participants were excluded because they were continuing patients, dropped out of care before completing enrollment, were starting residential or inpatient treatment, were active duty military personnel, or were too cognitively impaired to consent. Participants were recruited through provider referral or via mailed letter, which was approved by the institutional review board that reviewed the study (the letter included an opt-out option), followed by a telephone call. Interested patients met with a research assistant who explained the study and obtained consent. Of 1,156 eligible patients, 358 (31%) agreed to participate and completed a baseline survey.

Treatment plans were available for 350 participants at the time of initial assessment; these plans were diverse, including group psychoeducation, other group therapies, individual psychotherapy, case management, or psychiatric management, but did not differ by condition. Sixty-three percent (N=220) of the participating veterans were scheduled to be seen weekly, 20% (N=71) were scheduled to be seen monthly or biweekly, 11% (N=39) had psychotherapy of no specified frequency, and 6% (N=20) had no psychosocial treatment. Only 31 participants (9%) were scheduled to receive one of the evidence-based therapies for PTSD: cognitive processing therapy (CPT;

32) or prolonged exposure (

33). A total of 240 participants (68%) were prescribed an SSRI or SNRI during the study period, of whom 200 (83%) had continuations of prior prescriptions, 25 (10%) had new prescriptions initiated during the three-month intervention period, and 15 (6%) had prescriptions initiated during the nine-month follow-up. Eighty-seven participants (24%) were prescribed prazosin, including 60 (17%) with continuations of prior prescriptions, ten (3%) with new prescriptions initiated during the intervention period, and 17 (5%) with new prescriptions initiated during follow-up. Because of the small number of new prescriptions, new and continued prescriptions were combined in all analyses.

Procedures

Study procedures were overseen by institutional review boards at each study site, and all of the veterans provided written informed consent to participate. Random assignments were made centrally by using the randomization technique of Efron (

34) and then stratifying within site, by gender, and by whether participants had served in Iraq or Afghanistan. After random assignment, one participant transferred to a residential treatment program and another withdrew and asked that his data not be used, leaving a final sample of 356, of which 191 were in the TCM intervention and 165 were in usual care. Surveys at four- and 12-month follow-ups were obtained by mail, with mail and telephone follow-up, by using the Dillman method (

35). Completion rates were 68% (N=242) and 60% (N=213), respectively. [A figure in the

online supplement to this article shows the study conditions and participation rates.]

Telephone Care Intervention

Participants randomly assigned to usual care received regular care from their counselors or psychiatrists. Participants in the TCM arm received usual care augmented by fortnightly telephone monitoring and support during their first three months of treatment. The telephone monitoring intervention was delivered from a centralized call center by clinical psychology graduate students supervised by a clinical psychologist. If participants did not answer the telephone, the care manager left a message and toll-free call-back number and made two additional contact attempts. After three attempts, participants were not contacted until their next scheduled call. If the telephone number was disconnected, we attempted to obtain a new number from a family member or friend whom the participant had provided as a contact.

Telephone care managers followed a semiscripted protocol to assess participants’ treatment attendance, medication compliance and side effects, symptom severity (PTSD, depression, and anger were each assessed on a 1–10 Likert scale, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms), self-efficacy for coping with symptoms, substance use, suicidality, and risk for violence (

36). Telephone care managers verbally reinforced positive behaviors, such as using coping skills or adhering to treatment. They provided brief problem-solving support or motivation enhancement to help address behaviors that could interfere with treatment, such as missing appointments, misusing substances, or not communicating concerns to providers. Telephone care managers alerted their supervisor and the participant’s provider if the participant was at risk of self-harm and informed the participant’s provider if symptoms increased or if substance abuse began.

Measures

The primary outcomes were assessed at baseline, four months, and 12 months with the

DSM-IV version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL;

37) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D;

38). Substance use outcomes were assessed with the alcohol and drug composite scores from the self-report version of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI;

39,

40). Aggressive behavior was assessed with a six-item index (range 0 to 8) adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale (

41), which expands on a four-item index widely used with VA patients (

42). Quality of life was assessed with a scale developed for the Veterans Affairs Military Stress Treatment Assessment study (

43).

Mental health outpatient treatment visits during the three-month intervention period and the nine-month follow-up period were determined from the National Patient Care Database. Mental health visits were classified as either PTSD psychotherapy (encounters with both a PTSD diagnosis and a psychotherapy procedure code) or other mental health visits (mental health visits without a PTSD diagnosis or visits for PTSD which did not include psychotherapy). For participants prescribed psychiatric medications, MPRs (calculated as days’ supply of medications divided by total days) for the 12-month study period were determined from the Decision Support System Pharmacy National Data Extracts according to procedures used by Lockwood and colleagues (

44). Distance from participants’ homes to the nearest VA clinic or VA medical center was determined from VA administrative data. At baseline, four months, and 12 months, therapeutic alliance with the mental health provider that participants saw most often was assessed with the short form of the Working Alliance Inventory (

45). At those same time points, treatment outcome expectations were assessed with a procedure developed by Battle and colleagues (

46).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis, with multiple imputation of missing data (

47,

48). All analyses were conducted with R version 2.9.2 (

49), and multiple imputations were completed with the R MICE library (

50). Our sample size provided 90% power to detect small (d=.20) effects of condition on outcomes. To address our primary hypotheses, we used negative binomial regression to assess the effect of study condition on number of PTSD psychotherapy visits and total mental health visits completed, and we used linear regression to determine the effects of study condition on MPRs. To address our secondary and tertiary hypotheses, we used mixed-effects regression models to assess the effect of condition and study site on slope of improvement in each of our clinical outcomes over the 12-month study period and to assess whether treatment attendance and MPR mediated these effects. All models included fixed effects for study site and for treatment utilization in the year before the study. Exploratory regression analyses tested whether there were significant interactions between treatment condition and each of our five moderators in predicting four outcomes: treatment attendance during the three-month intervention period, MPRs over the 12 months of the study, and slopes of PTSD and depression symptoms over the 12 months of the study.

Results

Participant characteristics are shown in

Table 1.

Telephone care managers contacted 182 (95%) of the 191 remaining participants in the intervention condition and completed a mean±SD of 5.1±1.3 of the six planned calls for each participant. Telephone contact duration ranged from one to 92 minutes (25.1±11.1). For 125 (65%) TCM participants, care managers informed their providers of new problems that emerged during the phone calls. These problems included increased symptoms (reported in 324 out of 926 phone calls, 35%), problems with scheduling or attending appointments (222 calls, 24%), suicidal ideation (65 calls, 7%), aggressive ideation (56 calls, 6%), heavy drinking (74 calls, 8%), drug use (54 calls, 6%), or medication noncompliance (55 calls, 6%).

Adverse Events

We had 13 non-study-related adverse events. One participant was hospitalized for alcohol withdrawal and was later reported deceased. One participant voluntarily entered a residential alcohol treatment program and was excluded from the study because he was no longer receiving outpatient care. Two participants had a psychiatric hospitalization for suicidal ideation. Five participants were hospitalized for medical reasons. Two participants were incarcerated, and two were in car accidents.

Treatment Utilization

During the three-month intervention period, participants in the TCM condition completed 43% more mental health visits (5.9±6.8) than did those in usual care (4.1±4.2) (incident rate ratio [IRR]=1.36, χ

2=6.56, df=1, p<.01). More specifically, veterans in the TCM condition completed significantly more sessions of psychotherapy for PTSD (3.1±5.2) than did those receiving usual care (2.2±3.3, IRR=1.45, χ

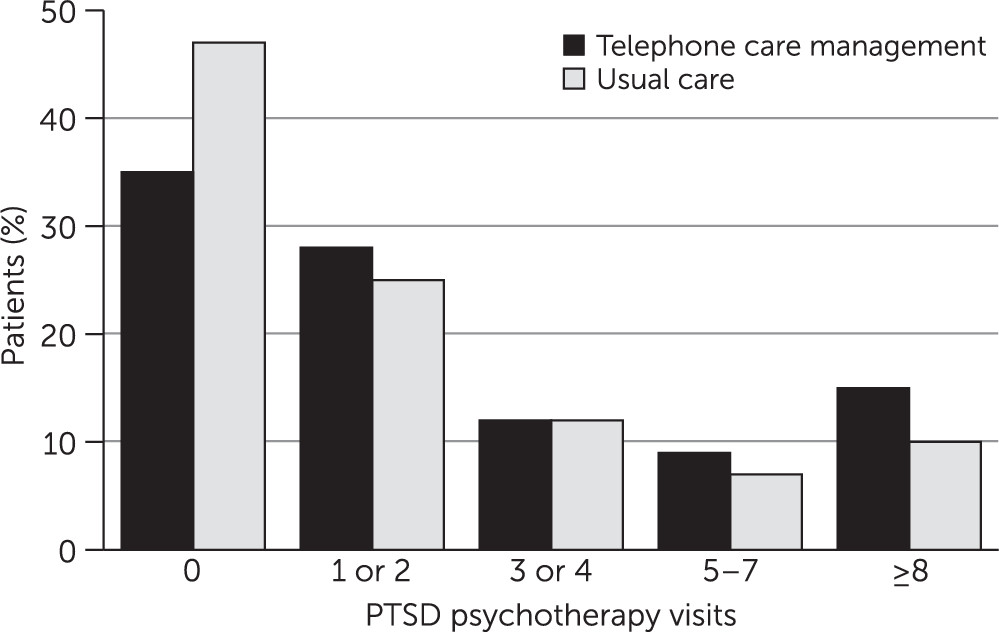

2=8.4, df=1, p<.001). Nearly half of the usual care participants (47%, N=77) completed no PTSD psychotherapy visits, compared with 35% (N=67) of those receiving TCM (

Figure 2). Yet, few participants in either the TCM (15%, N=29) or the usual care (10%, N=16) conditions completed eight or more sessions of psychotherapy for PTSD during the initial three-month period. The number of other mental health visits (nonpsychotherapy or non-PTSD visits, or a combination) completed during the intervention period did not differ significantly between the TCM (2.5±3.0) and usual care (1.9±2.1) conditions (

Table 2). The number of PTSD psychotherapy visits or other mental health visits in the nine-month postintervention period did not differ by condition.

There was no difference by condition in MPRs for SSRIs, SNRIs, or prazosin prescriptions. None of the risk factors for low attendance (prior-year treatment visits, distance to care, treatment expectancies, therapeutic alliance, or being a veteran of Iraq or Afghanistan conflicts) moderated the effects of TCM on either the number of PTSD psychotherapy sessions or other mental health visits completed during the intervention period.

Clinical Outcomes

There was no improvement in clinical outcomes. The 12-month slopes of PTSD, depression, alcohol problems, drug problems, aggressive behavior, and quality of life did not improve significantly over time and did not differ by intervention condition (

Table 3).

Our model of TCM presumed that increasing treatment visits and medication refills would improve participant outcomes. To explore this hypothesized mediation mechanism, we examined the associations between each of our dose-of-care measures (PTSD psychotherapy visits, total mental health visits, SSRI or SNRI MPR, and prazosin MPR) and slope of improvement on each clinical outcome (PTSD, depression, alcohol problems, drug problems, aggressive behavior, and quality of life). None of the dose-of-care indicators was significantly associated with any clinical outcome.

Discussion

We hypothesized that TCM would increase treatment attendance and that this would improve participants’ PTSD, depression, and other clinical outcomes. Consistent with prior studies, TCM improved treatment attendance (

26,

27,

29). This effect did not persist in the follow-up period after telephone contacts stopped. TCM had no effect on medication refills, perhaps because most patients were continuing existing prescriptions. Telephone monitoring may be more valuable for patients initiating a new prescription, both to manage side effects and to ensure sufficient adherence to evaluate whether the new medication is helpful.

Our hypotheses that TCM would directly or indirectly improve clinical outcomes were not supported. A mean difference of 1.5 in-person visits over three months may not have been large enough to be clinically meaningful. Our finding that only 10% to 15% of participants completed eight or more sessions of PTSD psychotherapy during the three-month intervention period is similar to some prior reports (

4).

The impact of TCM may have been limited by the heterogeneity of treatments that participants received. We accepted patients starting any type of treatment for PTSD, including trauma-focused therapy, other weekly psychotherapies, psychoeducation groups, art therapy, case management, or medication management. Not all of these are likely to be equally effective (

51,

52). Consistent with some other VA studies (

53,

54), only a small proportion of all PTSD psychotherapy patients were scheduled for evidence-based psychotherapies.

This treatment diversity may explain why pre-post changes in participant outcomes were small and unrelated to the number of mental health treatment sessions participants attended. Another study of veterans receiving usual VA care found modest improvements overall and no relation between treatment dose and outcomes (

55). Other research found that adherence to SSRI and SNRI medications did not lower risk of rehospitalization after discharge from residential PTSD treatment (

44). Yet when veterans initiated prolonged exposure therapy, a psychotherapy known to be efficacious for PTSD, those who completed a full course of treatment had better outcomes than those who dropped out (

56). This suggests that adherence improves outcomes when the treatment itself is highly effective.

The clinical impact of care management likely depends on the effectiveness of the treatment it is supporting. In the RESPECT-PTSD trial, conducted in primary care, collaborative care improved treatment attendance but not clinical outcomes (

29). In that study the dose of psychotherapy was small, and few participants received trauma-focused psychotherapy. In contrast, the collaborative care arm in the Telemedicine Outreach for PTSD (TOP) trial provided remote evidence-based CPT to participants who wanted it, in addition to telephone support and pharmacology consultation (

30). The TOP collaborative care arm had significantly better clinical outcomes than usual care, and the effect was mediated by the proportion of participants (25% versus 5%) who completed CPT.

This study had several limitations. We had too few participants receiving prolonged exposure therapy or CPT to test whether the clinical effects of TCM were moderated by type of treatment. This study was conducted with patients who had already initiated mental health treatment. Effects of telephone contact may be stronger for people not yet engaged in care (

57,

58). This study was conducted within a single integrated health care system, the Veterans Health Administration. It is unclear how well these results generalize to other care settings, where services may be more fragmented. Furthermore, it was conducted with predominantly male veterans, so findings may not generalize to nonveterans or to women.

Conclusions

TCM increased veterans’ attendance in PTSD treatment but did not improve their clinical outcomes. A growing literature confirms that TCM can improve patients’ entry into and retention in mental health treatment. However, the clinical impact of telephone support is contingent on the overall effectiveness of the mental health treatment that is being supported.