Despite increased interest and legislative action related to widening access to mental health care services in the United States, there is little research on the quality of such services, particularly within the context of inpatient care (

1). Public reporting of hospital quality, however, has been an important component of value-based purchasing in the United States (

2). Until now, the quality of inpatient psychiatric care has not been similarly subjected to public scrutiny.

In 2008, The Joint Commission (TJC), in collaboration with the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors and Research Institute, the National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, and the American Psychiatric Association, established a set of seven core quality measures for inpatient psychiatric care, known as the Hospital-Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services (HBIPS) measure set (

3). Although it can be argued that the HBIPS set focuses too narrowly on processes, these standardized measures were an important turning point in creating at least one mechanism for accountability, allowing researchers and regulators to assess quality variation between facilities, track quality improvement efforts over time, and tie quality of inpatient facilities to accreditation.

Beginning in 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began incorporating the HBIPS measures into the Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Reporting (IPFQR) program, a new pay-for-reporting program mandated by the Affordable Care Act (

4). The IPFQR program lowers annual payments by 2% for psychiatric facilitates that fail to report these quality measures. CMS’ measure set is scheduled to expand to 16 by the year 2017 and will include measures for continued care postdischarge, the patient experience, and other nonprocess domains.

Given the increase in data to be collected under the IPFQR program and the potential for these data to be linked to value-based purchasing, now is an opportune time to begin critically assessing the HBIPS measures as a way to inform future efforts. Moreover, the national climate regarding mental health care reform, which has focused on expanding access to care, necessitates a thorough understanding of the quality of available services.

To our knowledge, there exists no other published analysis of the HBIPS measures, and there is limited research evaluating the quality of inpatient psychiatric care in general. We asked three essential questions that parallel earlier research on inpatient hospital quality outside of the psychiatric context (

5): Overall, how well do psychiatric facilities perform on each measure? To what degree does performance on one measure predict performance on the other measures? Are there differences in quality as a function of whether the hospital’s ownership is classified as for profit, nonprofit, government other than the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), or VA?

Methods

We utilized TJC’s 2014 publically available HBIPS data (

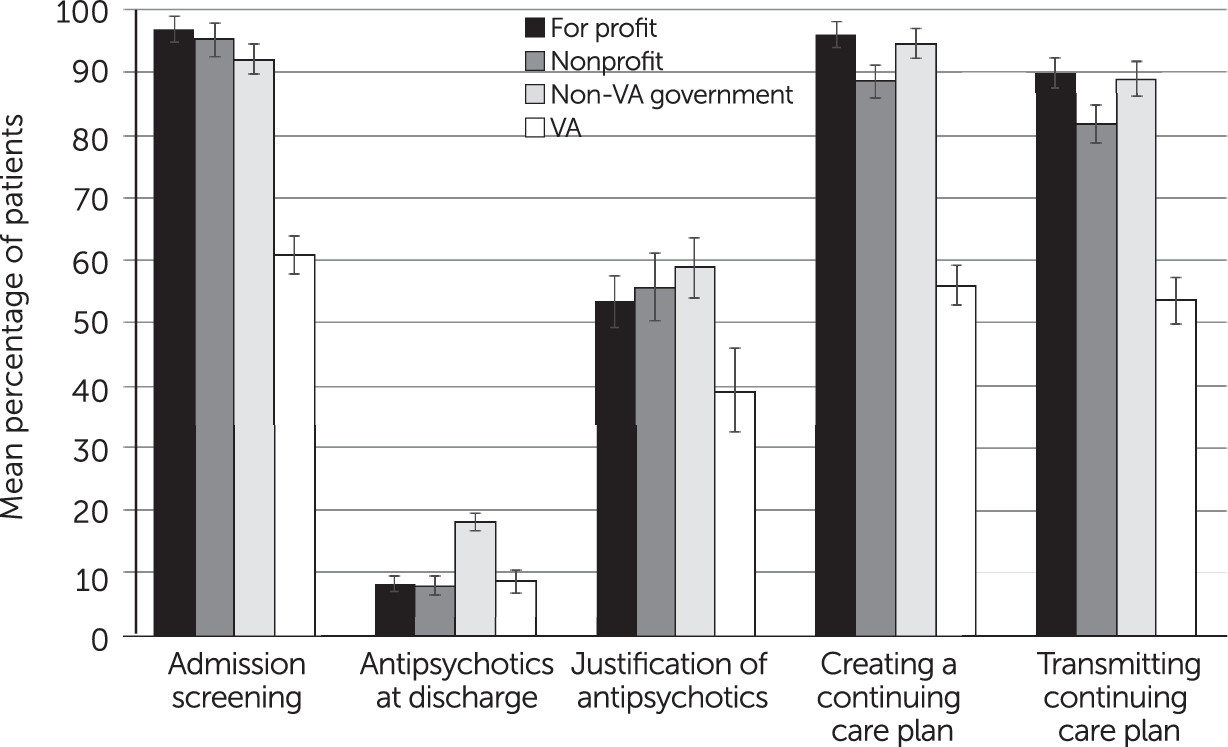

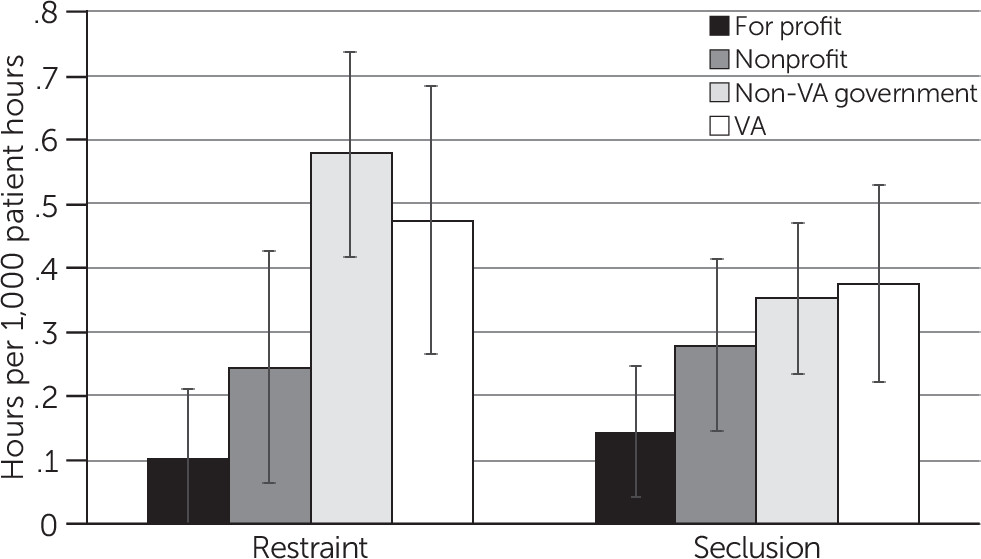

www.jointcommission.org). The seven HBIPS measures include percentage of patients who received admission screening for violence risk, substance use, psychological trauma history, and patient strengths; hours of physical restraint per 1,000 patient hours; hours of seclusion per 1,000 patient hours; percentage of patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications; percentage of patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications with appropriate justification; percentage of patients for whom a postdischarge continuing care plan was created; and percentage of patients whose postdischarge continuing care plan was transmitted to the next level of care provider upon discharge. Measures 2, 3, and 4 are negatively coded, meaning that lower values indicate higher quality of care. Measures 2 and 3 are calculated as average hours per 1,000 patient hours; all other measures are calculated as proportions of discharges.

Hospitals can choose to randomly sample records for the HBIPS measures either quarterly or monthly. For a quarterly assessment, according to TJC’s requirements, a hospital must gather a sample size equal to at least 20% of its quarterly patient population. If a facility’s population for a given quarter is fewer than 44 patients in a given age category, then all records are assessed rather than a sample. For a monthly assessment, if there are fewer than 15 patients in the population, then all records are assessed. Measures of restraint and seclusion cannot be based on samples; all records are assessed for these measures.

For the purposes of this study, we looked at overall performance on each HBIPS measure by TJC’s accredited psychiatric facilities over the entire year (2014). Of the 669 accredited hospitals represented in TJC's public data files, four hospitals did not report data for any measures. In addition to these four hospitals, three hospitals did not report data for measure 2, one hospital did not report data for measures 4 and 6, and 51 hospitals did not report data for measure 5. We linked each hospital to its ownership type (for profit, nonprofit, government other than VA, and VA).

Analyses

We assessed the mean, interquartile range (IQR), and covariance for the HBIPS measures by using Pearson's correlation and Cronbach's alpha. Next, we tested differences on each quality measure by type of hospital ownership by using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and pairwise comparisons, using the ownership type with the best results for each measure as the reference group.

Discussion and Conclusions

Measurement and reporting of the quality of inpatient psychiatric care are at a nascent stage. We took a first look at hospitals’ performance on the TJC's HBIPS quality measures, at the relationship between these measures, and at the differences in performance by hospital ownership. Our analysis found wide variation in performance by hospitals on most measures. Overall, facilities performed the best on admission screening and the worst on appropriately justifying the practice of discharging patients on multiple antipsychotics.

When we assessed covariance between the HBIPS quality measures, we found weak relationships between measures, which suggests either that the quality of inpatient psychiatric care is a multidimensional construct or that some or all HBIPS measures of quality are unreliable. Both measurement error and potential bias may vary by measure as a result of differences in data collection. In particular, administrative process measures might be more systematically captured relative to the clinical measures of restraint and seclusion. These findings suggest that it would be inappropriate to simply label certain facilities as “high quality” or “low quality” on the basis of HBIPS measures.

Despite the variability both within and between measures, it is clear that hospital ownership matters when it comes to quality of performance on all of the measures. In particular, the data provide reason for concern about the performance of VA hospitals as well as other government hospitals.

Whereas HBIPS measures appeared poorly correlated overall, three measures—admission screening, creating a continuing care plan, and transmitting the continuing care plan to the next level of care—were closely associated with each other. The strength of these relationships might be explained by the process-centered nature of the domains, given that they might operate under similar underlying mechanisms. We do not, however, know the ideal benchmark for each of these measures and whether low performers should model, or are capable of modeling, high performers. For example, although it might seem obvious that admission screening should be as high as possible, screening patients who present with more severe illness or who are not communicative might not be feasible. Further, there is no established “gold standard” or consistent criteria for restraint and seclusion, making it difficult both to interpret rates and to identify quality improvement pathways (

6).

We did not find systematic differences between for-profit and nonprofit hospitals, despite prior research suggesting that nonprofit inpatient psychiatric facilities might be better prepared from an organizational standpoint to offer high-quality mental health care compared with for-profit inpatient facilities (

7). Research on the association of ownership and quality in hospitals other than psychiatric facilities is inconsistent. Some research suggests that nonprofit hospitals are superior to for-profit and government hospitals on certain indicators of quality and within certain specialties. These differences, however, vary across time and by specific organizational characteristics (

8). Moreover, because of its distinct culture, policies, and reimbursement structures, inpatient psychiatric care cannot easily be compared with inpatient care for other conditions (

9).

The poor performance of the VA hospitals is congruent with a larger body of recent evidence suggesting that VA facilities have poor quality of care in general, which has recently garnered media attention (

10–

12). This study provides troubling evidence of the inferior performance of the VA hospitals in terms of psychiatric services, especially in regard to admission screening for trauma. Although trauma certainly is not limited to experiences of combat, veterans are considered by society, researchers, and policy makers to have a high prevalence of trauma (

13–

16). The apparent failure of the VA hospitals to screen for trauma—as well as substance use, violence risk, and patients’ strengths—warrants deeper investigation and potentially regulatory attention.

Differences in performance due to hospital ownership may be the result of differences in resources, training of staff, and case mix. The poor performance of the VA hospitals, in particular, might be partly explained by lack of funding. It is important to note, too, that our findings do not imply that for-profit ownership provides “good” or “standard” care simply because for-profit hospitals performed the best on most measures. Even the best hospitals showed some room for improvement in the process measures, and many critical dimensions of quality—including patient experience—are not represented in this initial measure set.

Our study was limited in its cross-sectional design, the narrowness of the seven HBIPS measures of quality, and the absence of patient-level characteristics, such as insurance coverage, race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, diagnoses, co-occurring conditions and disabilities, gender, and sexuality. Currently, TJC collects some patient characteristics data but does not release this information to the public or to researchers. TJC could facilitate efforts to understand and improve quality by making these data available. In particular, patient-level data would enable researchers to assess between-patient differences in experiences and quality of care as a function of certain patient characteristics and to more rigorously assess the role of hospital ownership in predicting quality above and beyond case mix. In addition, although facilities are subjected to audit by TJC, it is important to note that these measures are self-reported by facilities and could be subject to error or bias.

In the future, researchers and regulators should widen the scope of assessments for measuring the quality of inpatient psychiatric care. Assessments should include additional quality indicators that capture patient experiences, both short-term and longer-run health outcomes, and predictors of quality performance, such as hospital structure, teaching status, and staff training and turnover (

17–

19). These data are critically important not only to foster accountability but also to improve our understanding of the mechanisms that support high-quality inpatient care and optimal outcomes for an especially vulnerable patient population.