Outpatient commitment provisions have been written into law around the world (

1) and exist in 45 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (

2). These provisions have been described as assisted treatment (

3), a means to deliver involuntary treatment (

4), and a way to engender treatment compliance (

5). In civil commitment law, outpatient orders are almost universally recognized as “a least restrictive alternative to psychiatric hospitalization” for persons meeting the involuntary civil commitment standard of the jurisdiction. Outpatient commitment, which is initiated by a community treatment order (CTO) in Victoria, Australia, and most Commonwealth nations, is carried out in two primary ways. First, it is a form of conditional release whereby a patient is placed on an order after involuntary hospitalization as part of an aftercare plan and as a means to shorten the duration of the current hospital episode. This is by far the oldest and most used approach (

6). Second, a patient can be placed on a CTO while living in the community as a way of avoiding hospitalization, although this occurs infrequently (

7).

The utility of a CTO depends on the extent to which it meets the stated objectives written into the law (

7). For individuals who refuse intervention because of their symptoms of mental illness, these objectives include ensuring access to needed treatment by various means of service, focusing on the protection of the health and safety of self and others, and using the least restrictive alternative to psychiatric hospitalization to accomplish these goals. [A description of CTO use in Victoria is included in an

online supplement to this article.]

The CTO is designed to be a delivery system enabling the provision of unsought but required services that are thought to lead to positive health and safety outcomes with limited use of hospitalization (

7). In fact, a CTO is typically part of a package that includes the hospitalization preceding it. By design, the CTO should enable savings in hospital days by allowing clinicians to shorten the inpatient stay it follows. It should protect against untoward events after the inpatient stay, with either additional service provision or, as a result of the additional supervision it provides, rehospitalization to prevent negative health and safety outcomes.

This study built on previous work (

7–

9) by considering the effects of various components of the CTO legal mandate. It analyzed a second decade of new data to attempt to replicate the earlier findings and to add to the understanding of how CTOs fulfill the stated objectives written into the law. In 2000, at the outset of the decade under study, Victoria closed all its state hospitals and began relying on general hospital psychiatric services and CTOs to help ensure delivery of needed treatment objectives in a fully integrated health and mental health care system. This study addressed two considerations in the use of CTOs in Victoria, Australia. First, to what extent are patients selected for CTOs in need of treatment related to protecting their health and safety? Second, is the provision of such treatment delivered in a least restrictive manner—that is, in a way that contributes to reduced use of psychiatric hospitalization (

10)?

Results

Data on demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the sample are presented in

Table 1. The mean age of the sample at study outset was 34.0. More than half of the patients (56%) were male, were not educated beyond the 11th grade (52%), and were unemployed (60%). About half (49%) had never been married, and two-thirds (66%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Table 2 presents data on the treatment experiences of the two cohorts. Patients in the CTO cohort entered the mental health system at an earlier age than those in the non-CTO cohort (age 32.1 versus 35.5). During the study period, patients in the CTO cohort experienced 4.0 inpatient episodes on average (range 1–65), compared with 1.3 (range 1–39) for those in the non-CTO cohort. The CTO cohort averaged 38.0 inpatient days per episode, compared with 29.1 for the non-CTO cohort.

The CTO cohort experienced almost twice the number of community treatment episodes compared with the non-CTO group (6.0 versus 3.3), with almost 40% more treatment days per episode (26.6 versus 16.1). For the CTO cohort, an average of 2.3 of the community treatment episodes involved placement on a CTO. Overall, the CTO cohort experienced 25,696 total CTO episodes; 39.2% (N=10,021) of the CTO episodes ended in rehospitalization, and only 5.9% (N=1,516) were initiated from the community (that is, either initiated on the same day of hospital admission—the patient was brought in and immediately released on a CTO—or initiated more than three days after hospital admission).

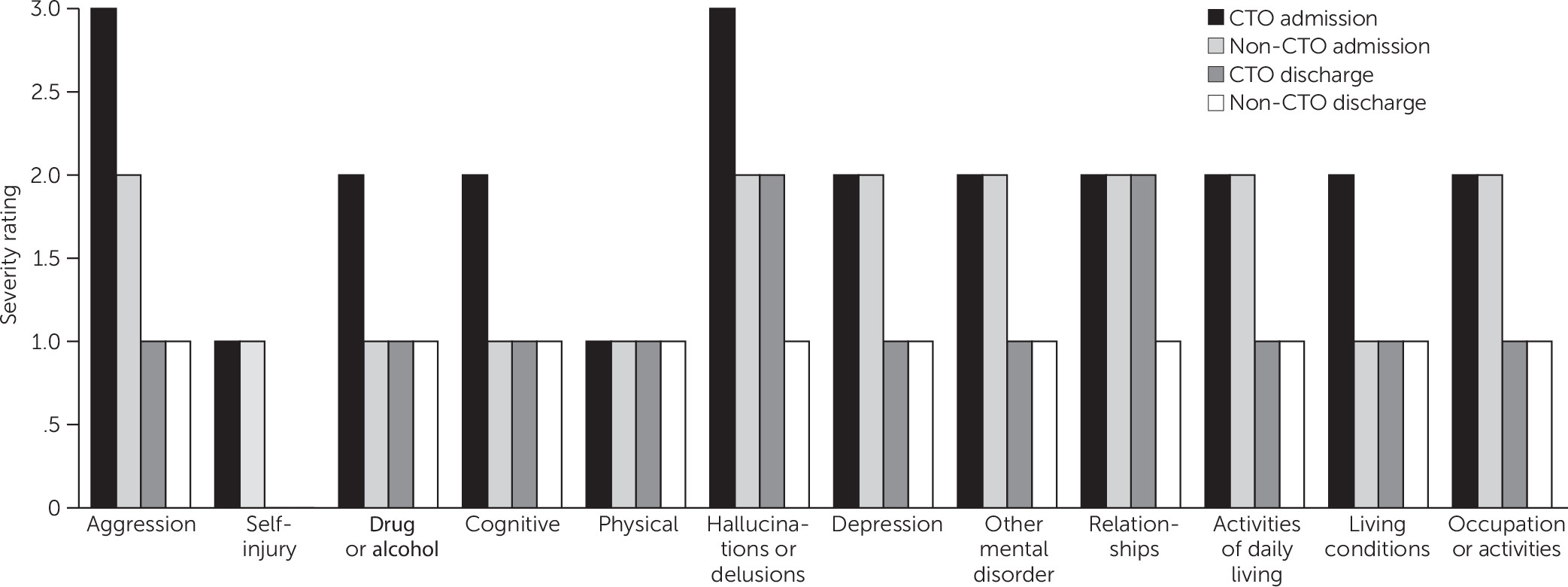

The CTO cohort entered inpatient care with clinical profile scores more severe than their non-CTO counterparts on all 12 HoNOS dimensions. Differences between cohorts in HoNOS scores on admission were statistically significant (p<.001) on all dimensions except for physical health, which was statistically significant at p=.002. The profile was more severe not only statistically but also clinically (that is, when scores are rounded to their nearest clinical anchor value). Although both groups manifested clinically significant problems at admission on all dimensions, clinically adjusted scores of the CTO group exceeded those of the non-CTO group on the following items: aggression, drugs and alcohol, cognitive dysfunction, and hallucinations or delusions (

Figure 1). The scores of both groups indicated not only a statistically but also a clinically significant problem on the eight other items, sufficient to allow inpatient care recommendations (

23).

HoNOS scores at discharge—the point at which CTO placement typically occurred for members of the CTO cohort—showed an abatement of problems associated with most HoNOS dimensions. However, the CTO group continued to have more severe problems than their non-CTO counterparts on all dimensions at discharge. The differences between cohorts were statistically significant differences (p<.001) on all dimensions except for other mental disorder (p=.009) and physical health (p=.051). In addition, compared with their non-CTO counterparts, the CTO patients continued to have clinically significant elevations in hallucinations or delusions and relationship issues (

Figure 1).

Table 3 summarizes the results of the logistic regression describing patient characteristics that were associated with an increased likelihood of being released from inpatient care on a CTO. The model evaluated 42 of 46 noncollinear variables and was significant (χ

2=9,056.94, df=42, p<.001). Patients were 5.47 times more likely to be selected for a CTO if they experienced a hospitalization of greater than the 34-day mean length of stay. In addition, the likelihood was greater (Exp(b)=1.60) with each additional hospitalization. For each unit increase in severity on the 4-point HoNOS item on hallucinations or delusions at hospital discharge, the likelihood of CTO assignment was increased (Exp(b)=1.28); the likelihood was also increased (Exp(b)=1.12) for each unit increase in severity on this item at hospital admission. In addition, the likelihood of CTO assignment was increased for each unit increase in severity at admission on the following three items: aggression (Exp(b)=1.15), disturbance in relationships (Exp(b)=1.05), and cognitive disturbance (Exp(b)=1.03). Being a male also increased the likelihood of CTO assignment (Exp(b)=1.13), as did having an interpreter at the mental health tribunal hearing (Exp(b)=1.23).

The OLS regressions considered the role of the CTO in the duration of an inpatient episode when all aforementioned controls and the propensity of a patient to be selected into the CTO sample were taken into account (

Table 4). The first model considered the overall effect of CTO assignment on average inpatient episode duration; its summary statistics were as follows: R=.704; adjusted R

2=.494, F=463.84, df=44 and 20,780, p<.001. Results indicated that placement on a CTO resulted in 4.6 fewer days per inpatient episode over the course of the study period (b=−4.61, p<.001). The second model considered the impact of a given CTO on inpatient episode duration; its summary statistics were as follows: R=.722, adjusted R

2=.522, F=515.66, df=44 and 20,780, p<.001. The model results indicated that each individual placement on a CTO resulted in a reduction of 10.4 days in the associated inpatient episode (b=−10.38, p<.001).

Results from the OLS regressions were replicated in the Poisson analyses. The average episode duration for the CTO cohort was estimated to be shorter than for the non-CTO cohort (Exp(b)=.960, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.955–.966), likelihood ratio χ2=8,372.35, df=20, p<.001). Each CTO episode was associated with fewer inpatient days (Exp(b)=.913; CI=.911–.914, model likelihood ratio χ2=8,500.39, df=45, p<.001).

Discussion

This study replicated findings from an analysis of data from a previous decade in Victoria (

7). As in the previous study, longer and repeated hospitalizations were strongly associated with selection for the CTO delivery system. Thus, from 2000 to 2010, it continued to be the case that a major consideration in the selection of individuals for placement on a CTO was experience of longer inpatient stays (≥34 days) and more inpatient episodes, compared with individuals not placed on a CTO.

In terms of least restrictive care, the results seem to support the objective of providing care in a way that involved reduced use of psychiatric hospitalization in each episode of care. After the analysis adjusted for treatment history, diagnosis, demographic factors, psychosocial profile, prison time, cultural disadvantage, social disadvantage of the postal code in which the patient resided, and the propensity of a patient to be selected into the CTO sample, placement on a CTO resulted in 4.6 fewer days per inpatient episode over the course of the study and a reduction of 10.4 inpatient days per CTO episode. These findings seem to confirm the goal of using CTOs to reduce the duration of inpatient episodes. They also replicate earlier findings in Victoria (

7) and in Western Australia (

15,

22). From 1990 to 2000, 8.3 days were saved per inpatient episode (

7). The decline to 4.6 days saved in 2000–2010 may indicate a shift in the system’s investment in community care.

Compared with the non-CTO cohort, the CTO cohort had more severe and clinically significant health and safety issues, particularly in the areas of aggression, hallucinations or delusions, cognitive disturbance, and disturbances in relationships. The CTO group was characterized by persistent health and safety problems, as indicated by repeated long-term hospitalizations, as well as persistent clinically significant symptoms. Thus the findings provide added justification, under the legal requirement to “prevent future deterioration” (

7), for the protective measures specified in a CTO treatment plan; these measures are considered in mental health board hearings, where independent assessments are conducted in the presence of rights advocates (

24).

It remains an open question with respect to the need-for-treatment component of the CTO criteria whether the patient would fail to get needed treatment without the involuntary provisions of the law. Previous research has supported the “involuntary component” of the law; findings indicate that when patients were brought under CTO supervision, they increased their use of mental health care to the level of a voluntary population and that they stopped making use of this level of service after CTO termination (

23). This finding is also consistent with results of a recent survey of caregivers, which reported that among those with experience caring for a person on a CTO, most believed that the CTO had been of benefit; in 89% of the cases, the person relapsed when the CTO was stopped and needed further treatment (

25).

The CTO is a delivery system for available treatment; it is not a vaccine with a potential to have carryover effects once the order is terminated; it does not prevent the recurrence of episodes of mental illness. Therefore, the CTO is only as effective as the treatment delivery system in which it is embedded and the extent to which that system makes treatment and supervision available (

26). At the outset of this second decade of research on CTO use in Victoria’s mental health system, all state hospitals were closed, and the state governmental unit, composed of individuals who were viewed as effective community care advocates and whose unit’s mission was the promotion of enhanced community care, was disbanded (

4). The system focus changed to one of integrated general medical and mental health care centered around the general hospital. Although community treatment during this second decade was available at a rate 40% higher for the CTO cohort than for the non-CTO cohort (26.6 contacts versus 16.1 contacts per community episode), the actual number of treatment contacts per community care episode fell from 35.6 to 26.6 (25%) for the CTO cohort, compared with 1990–2000, and from 23.0 to 16.1 (30%) for the non-CTO cohort (

7). Our previous work indicates that in this environment of more constrained resources, clinicians appear to have adopted a de facto triage system for investing their time in the most serious cases by discharging 15.9% of the patients with less severe symptoms prior to a CTO legal hearing and focusing on making the case for legal retention of patients with more serious illness—the result being that only 2% of patients who remained on a CTO long enough to get to a hearing (at eight weeks after the CTO start date) were discharged after the hearing (

24).

The objective of CTO community care contacts also seems to have changed. The analyses regarding the impact of community treatment days on days per inpatient episode went from a negative relationship in the 1990–2000 cohort, indicating that treatment days contributed to a reduction in inpatient days per episode over the decade, to a finding in 2000–2010 indicating that treatment days were associated with an increase of a fraction of a day in the duration of an inpatient episode in interaction with a CTO. These results appear to show that the objective of the community treatment delivered in the second decade changed from aggressive action to maintain people in the community to a focus on providing services when absolutely required, such as by following up with patients who had a longer hospital stay and posed greater risk on release, meeting patients’ special needs, dealing with crises, and salvaging potentially failing CTO-associated community care episodes by bringing patients back to the hospital for needed treatment. In fact, 39% of the CTOs ended in patient rehospitalization.

The limitations of this study derive from its reliance on administrative data, which are not collected for purposes of research. Quality-of-life psychosocial assessments were based on clinician, not patient, perspectives. Future studies should take into account patients’ points of view (even if by a simple quantitative self-rating) when evaluating the impact of CTOs on quality of life. In addition, the analyses relied on correlational measures that did not yield full certainty of causal inference because of potential selection bias. Nevertheless, the study examined the experience of an entire population over the course of ten years, and it replicates and adds depth to previous findings. Also, no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of outpatient commitment have been completed that randomized at the outset of an inpatient episode that was followed by release to a CTO—that is, as opposed to randomization at release from the hospital. Thus RCTs discount and provide no documentation on a random basis of the saving of hospital days attributable to early release to a CTO (

27,

28), and by doing so they ignore the true contribution of the CTO to limiting hospitalization time. Furthermore, for ethical reasons, studies do not use random assignment with individuals who are believed to be dangerous, which, as demonstrated in this study, is a core behavioral criterion that separates those placed on a CTO from those not placed on a CTO. As a consequence, completed RCTs involving outpatient commitment suffer from selection bias. If strict causal inference limits are used, then the conclusions of those studies apply only to patients who are not deemed to be dangerous—that is, those who are less likely to be selected for outpatient commitment (

28). Finally, the issue of selection bias seems less pertinent to this study; the finding that hospital days were saved because patients assigned to CTOs were discharged to less restrictive community care is opposite to the expected finding, which is that the more severely ill CTO cohort would require more hospitalization than the non-CTO cohort.