Over two decades, substantial evidence for the effectiveness of collaborative care models for treating depression has been demonstrated in primary care (

1–

3) and in obstetrics and gynecology clinics (

4). More recently, a multicomponent collaborative care intervention, MOMCare, has been shown to be effective in reducing perinatal depression severity and increasing remission rates among socioeconomically disadvantaged women (

5,

6). Although these collaborative care programs differ in detail, the key active ingredients include provision of high-quality depression care (that is, adequate psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy dosage) delivered by care management staff (for example, nurses or social workers), a psychiatrist, and a primary care or obstetrics provider. This model also involves active and sustained measurement of outcomes and follow-up according to stepped-care principles by which treatment is systematically adjusted if patients are not improving (

7,

8).

Perinatal depression has broad impacts and poses significant cost to a wide range of stakeholders. Depression during pregnancy has been associated with low birthweight, prematurity (

9), and postpartum depression (

10). Antenatal and postpartum depression have adverse, lasting effects on maternal, infant, and child well-being (

11–

13). Antenatal depression alone is predictive of developmental adversity in childhood and adolescence (

12,

13). Perinatal depression has large, adverse economic effects outside the health system, including loss of work productivity, low educational attainment, and marital instability (

14–

19).

Implementation of improved depression care by health insurers and health systems, however, depends on the balance of costs and benefits to these stakeholders. This study examined costs from a health system perspective, especially regarding poor women from racially and ethnically diverse groups, who are at least twice as likely as middle-class women to meet diagnostic criteria for major depression during pregnancy (

20). To date, the incremental benefit of collaborative care for perinatal depression has not been evaluated.

Given the considerable evidence that comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may diminish or delay depression treatment response, we previously conducted a preplanned secondary analysis to investigate whether comorbid PTSD moderated depression outcomes and quality of care in MOMCare, an 18-month collaborative depression care intervention providing a choice of brief interpersonal psychotherapy (brief IPT) or antidepressants for pregnant women, compared with usual care (enhanced public health maternity support services [MSS-Plus]) (

6). We found that for socioeconomically disadvantaged women, MOMCare reduced perinatal depression severity, increased remission rates, and improved work and social functioning to a greater extent for those with comorbid PTSD than for those without PTSD (

6). In the study reported here, we looked at the incremental cost and benefit of treating socioeconomically disadvantaged women who had antenatal depression with and without comorbid PTSD. The study lasted 18 months—from midpregnancy to 15 months postpartum—a longer time span than examined in previous cost-effectiveness studies (

21–

23). A study duration longer than six or 12 months would be able to detect the longer-term benefits of a short-term investment in improved depression care. Added costs of improved depression treatment concentrate in the first months of treatment, whereas clinical and economic benefits may continue to accrue many months afterward (

24).

This study makes two contributions to the literature on the cost-effectiveness of organized care for depression compared with enhanced usual care. First, it focused on perinatal depression from pregnancy through 15 months postpartum—a public health issue of high importance because of its adverse effects on fetal, child, and adolescent development. Second, it took into account the effectiveness and cost of treating different types of perinatal depression, ranging from “less complicated” to more “difficult to treat” (

25). The latter condition typically involves comorbid anxiety disorders or difficult psychosocial contexts, such as living in poverty.

We predicted that MOMCare would lead to more days free of depression and a positive incremental net benefit for depressed women with comorbid PTSD, compared with MSS-Plus. We expected that depressed women without comorbid PTSD would show equivalent improvement in net benefit and on cost outcomes in MOMCare and MSS-Plus.

Methods

A randomized, controlled trial with blinded assessment was designed to evaluate the MOMCare collaborative care intervention for perinatal depression. From ten county public health centers, pregnant women between 12 and 32 weeks gestation were randomly assigned to an 18-month intervention added onto MSS-Plus versus MSS-Plus alone, with follow-up assessments at three, six, 12, and 18 months. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved the study, informed consent was obtained from participants, and safety was monitored by a Data Safety Monitoring Board. Details on study interventions, methods, therapist training, and fidelity are described elsewhere (

5,

6,

26).

Participants

Study recruitment occurred between January 2010 and July 2012. MSS social workers and nurses routinely screened pregnant patients for depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) (

27) and referred patients who scored ≥10 to the study. After referral, master’s-level social workers serving as depression care specialists (DCSs) in the study conducted screenings to assess inclusion criteria: ≥18 years of age, a diagnosis of probable major depression on the PHQ-9 (

27) or a diagnosis of probable dysthymia based on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI 5.0) (

28), 12–32 weeks gestation, telephone access, and English speaking. We refer to major depression and dysthymia as “probable” because we did not use a clinical interview to make these diagnoses. Exclusion criteria included acute suicidal behavior or multiple (two or more) suicide attempts, schizophrenia as measured by the MINI, bipolar disorder as measured by the MINI, recent substance abuse or dependence as measured by the CAGE-AID (

29), severe intimate partner violence necessitating crisis intervention, or currently seeing a psychiatrist or psychotherapist.

MSS-Plus Usual Care Condition

Participants randomly assigned to MSS-Plus received a more intensive version of MSS. MSS is the usual standard of care in the public health system of Seattle–King County for pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid and is delivered by a multidisciplinary team of social workers, nurses, and nutritionists who offer case management and facilitate contact with the obstetrics provider to promote healthy pregnancies and positive birth outcomes. Pregnant women scoring ≥10 on the PHQ-9 were eligible for MSS-Plus, which entailed more time with their multidisciplinary team. MSS-Plus providers did not provide evidence-based depression care but referred depressed patients for mental health treatment in the community or to the patient’s obstetrics provider. Study participants received MSS-Plus in their respective public health centers.

MOMCare Collaborative Care Intervention

Participants randomly assigned to MOMCare received not only MSS-Plus but also collaborative depression care, which is a systematic approach for reducing depression severity that includes evidence-based depression treatment (for example, a choice of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both) and active, sustained measurement of outcomes and follow-up according to stepped-care principles (

7,

8). The DCSs collaborated with their patient’s obstetrics provider, providing updates on patient progress and collaborating on medication management if indicated. MOMCare sessions were provided in the public health centers, by phone (

30), in community settings, and, infrequently, at home. MOMCare included a number of novel components, including an initial pretreatment engagement session involving problem solving in regard to barriers to care and case management to meet basic needs (

26).

Brief IPT (eight sessions) was derived from IPT (16 sessions), which has demonstrated efficacy in treating acute and persistent depression (

31,

32) as well as antenatal and postpartum depression (

33,

34). After completion of acute treatment, maintenance sessions continued throughout the baby’s first year. For women requesting antidepressants, the study psychiatrist made recommendations to physicians via a DCS usually for a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, on the basis of a clinical algorithm incorporating the patient’s current medications or past response to antidepressants.

We employed a stepped-care treatment approach; women with less than 50% improvement in depressive symptoms by six to eight weeks received a revised treatment plan. Women receiving brief IPT alone could augment with antidepressant medication. Women on medication alone could receive an increased dosage, medication change, or augmentation with brief IPT—or all three of these options.

A DCS followed participants every one to two weeks (in person or by telephone) during the acute phase of treatment (three to four months postbaseline) and monthly during the maintenance phase (up to 18 months postbaseline) once a clinical response (≥50% decrease in PHQ-9 score from baseline) or remission (PHQ-9 score <5) was achieved. At each contact the DCS monitored treatment response with the PHQ-9. Medication and brief IPT recommendations were made at weekly meetings with the DCSs, study psychiatrist (WK), and principal investigator (NKG).

Measures

Participants received blinded telephone assessments at baseline and three, six, 12, and 18 months. The primary outcome was depression severity on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–20 (SCL-20) (

35). Probable PTSD was determined by a clinical algorithm from the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version, which has been shown to have the highest sensitivity and specificity for a

DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD (

36).

Effectiveness of each treatment condition was summarized by the number of depression-free days (DFDs) over 18 months, using the method originally developed by Lave and colleagues (

21) and adapted by Simon and colleagues (

22–

24) for the SCL-20 depression scale. For each assessment, an SCL depression score <.7 was considered depression free, a score of 1.5 was considered fully symptomatic, and scores in between were assigned a proportional value.

Costs for MOMCare intervention services provided by study staff were calculated by using actual salary and fringe benefit rates plus a 30% overhead rate (for example, space and administrative support). The resulting unit costs were $80 for each DCS visit (typically 45–60 minutes) and $31 for each DCS telephone contact (typically 20–30 minutes). These costs included the time required for outreach efforts and record keeping. Intervention costs over the study period also included a fixed $247 cost per patient for caseload supervision and information support. We applied 2013 costs to all service units of the intervention to address inflation. Costs and benefits accrued over the same time period. Therefore, we did not use discounting because of the short time horizon over which costs and benefits were measured.

Additional depression care data (on the previous three- to six-month use of specialty mental health visits and medications) were collected by the Cornell Services Index (CSI) at each assessment (

37). The CSI is a reliable method to assess health service use and was successfully used in the cost-effectiveness analysis from IMPACT, a collaborative depression care intervention for older adults (

38). Additional depression care costs were estimated by Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts (

39).

We did not include costs of usual care in the study because MSS-Plus was not designed to provide depression care. Also, utilization rates of MSS-Plus across the study period did not differ by group condition.

Incremental cost for the MOMCare intervention compared with MSS-Plus was calculated for depression treatment cost, which included any costs of the intervention plus mental health services costs directly related to depression treatment (for example, specialty mental health treatments and prescriptions) (

24).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were based on original assignment regardless of treatment received. Primary analyses included participants who had complete mental health services data on the CSI (from baseline across the 18-month study period) (N=152, 93%), including six patients for whom missing data were interpolated on the basis of nonmissing proximal data points (four in MSS-Plus and two in MOMCare, all with PTSD). Those with missing cost data at the final data point were not included in the initial analysis (N=12). Initially, we used the analysis of covariance method, controlling for baseline depression severity and depression care costs prior to study entry, to estimate gain in DFDs for women with depression and comorbid PTSD in MOMCare and MSS-Plus and for women with depression alone in MOMCare and MSS-Plus. After the initial analysis, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to correct for those with missing cost data (N=12) by using six imputations and the gamma regression method to correct for the skewed distribution of cost data. [More information about the sensitivity analysis is included in online supplement 1 of this article.] Employing gamma regression allowed us to assess the sensitivity of the linear model to skewness in cost outcomes, controlling for baseline depression severity and service use costs prior to study entry.

Results

Of the women who were eligible and randomly assigned to MOMCare or MSS-Plus, those who participated in the baseline assessment did not differ significantly from those who did not in demographic or clinical characteristics. [A flowchart illustrating recruitment, intervention delivery, and follow-up assessments for participants is included in online supplement 2.] Complete SCL-20 depression data from baseline to 18-months postbaseline were available for 97% (N=160) of the sample. Those missing SCL-20 data did not differ from those with complete data in treatment assignment or demographic and clinical characteristics. Participants with complete cost data (93%, N=152) and those without complete cost data (7%, N=12) did not differ in baseline SCL-20 depression severity or other demographic variables; however, those with partial data were more likely to have probable PTSD (χ2=5.55, df=1, p<.05) and to have been randomly assigned to MSS-Plus (χ2=4.14, df=1, p<.05).

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with and without PTSD who were randomly assigned to the two treatment conditions. As we previously reported (

6), participants with comorbid PTSD had greater depression severity at baseline than those without PTSD and were less likely to be employed. No significant differences by treatment group and PTSD status were noted in maternal general medical comorbidities, pregnancy complications, emergency department visits, inpatient general medical or psychiatric visits, outpatient medical visits, home health care nursing services, laboratory or other tests, physical or occupational therapy, or number of MSS-Plus visits.

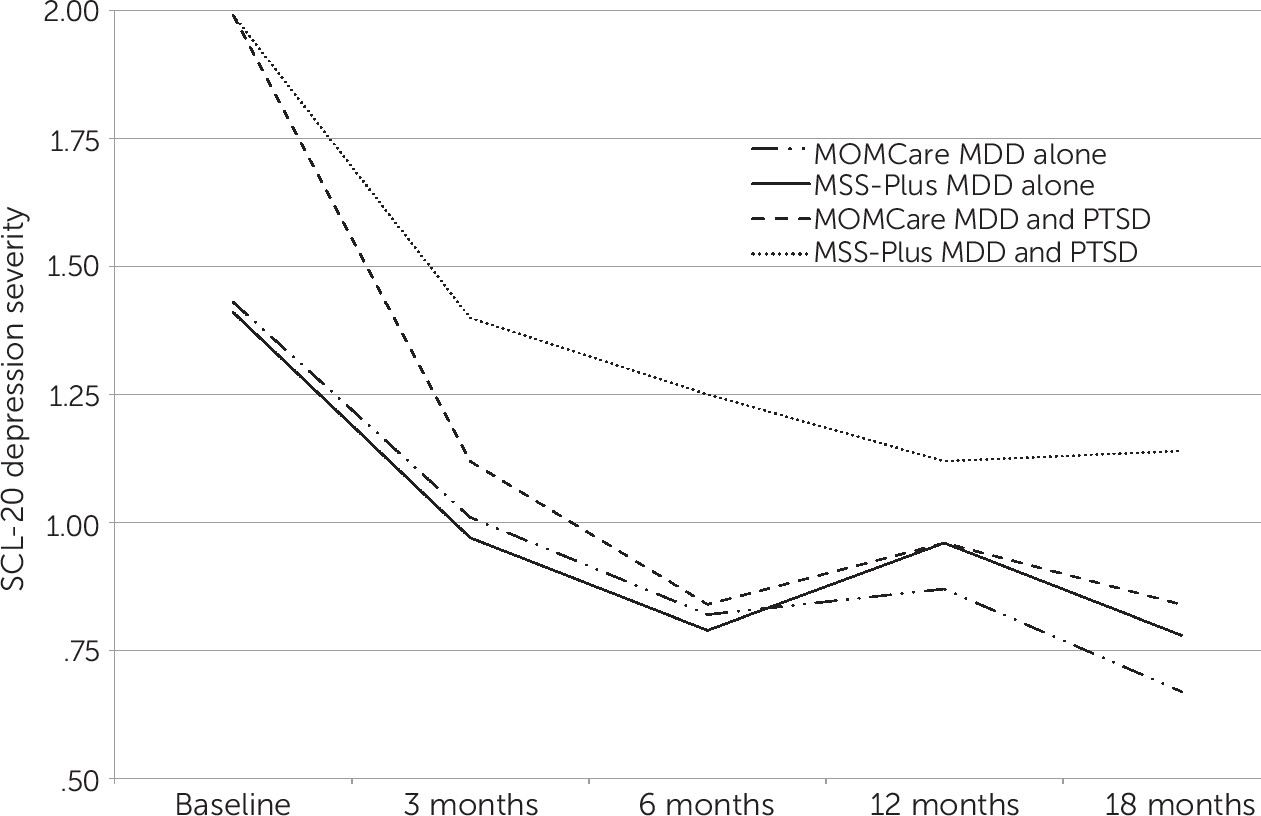

Mean SCL-20 depression scores are shown in

Figure 1 for the four treatment-by-PTSD subgroups. As previously reported (

6), the MOMCare intervention was found to be more effective than MSS-Plus in reducing depression severity for women with comorbid PTSD. Women without comorbid PTSD showed similar improvement in both treatment conditions.

Costs of the MOMCare intervention and other health services costs for depression care, as well as the gain in DFDs, are shown for the four subgroups in

Table 2. For women with comorbid PTSD, total depression care costs in the MSS-Plus condition were $776, compared with $2,088 for those in MOMCare—a difference of $1,312. Balanced against this added cost for those in MOMCare was the difference in DFDs. Compared with their counterparts with comorbid PTSD in MSS-Plus, women with PTSD in MOMCare experienced 68 more DFDs over 18 months (310 days minus 242 days) (F=4.56, df=1 and 92, p<.05).

For participants with major depression alone, the total costs of depression care were significantly higher in MOMCare ($1,737) than in MSS-Plus ($570)—a difference of $1,167. Balanced against this added cost, women without comorbid PTSD in MOMCare had only 13 more DFDs than their counterparts in MSS-Plus (347 days minus 334 days), a difference that was not statistically significant.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis by using six imputations to correct for missing cost data at endpoint (N=12) and gamma regression to correct for the skewed distribution of cost data. The results were essentially the same as those observed in the initial analysis.

Discussion

In our incremental benefit-cost study, we found that the MOMCare intervention, compared with MSS-Plus, yielded substantial long-term clinical benefit for pregnant women with major depression and PTSD. Clinical benefit of the MOMCare program among women without comorbid PTSD was estimated as modest and did not exceed what might be expected by chance. In both groups, the estimated net increase in the cost of the MOMCare program was on average $1,240 (average of $1,167 for major depression without PTSD and $1,312 for major depression with PTSD) (

Table 2).

The economic value of an additional day free of depression is not clearly delineated and may vary across demographic groups. Previous studies have presumed a value of $15 to $25 for each additional DFD (

21–

23). Considering the risks of perinatal depression to mother and baby, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged women, it may be judicious to place a high value on a DFD (for example, $20). Assuming a valuation of $20 for an additional DFD, the incremental net benefit of the MOMCare program for women with comorbid PTSD was positive, calculated as $48 (that is, 68 additional days free of depression multiplied by $20 per day minus the incremental cost of $1,312). At that same valuation of $20 per day, the incremental net benefit for women without comorbid PTSD was negative, calculated as –$907 (that is, 13 additional DFDs multiplied by $20 per day minus the incremental cost of $1,167). When a narrow or conservative estimate for benefits of depression treatment is used, the added costs of the MOMCare program for women with comorbid PTSD were more than offset by benefits of better depression outcomes.

Arguably, the valuation of an added DFD could be even higher given the benefits not only for the mother but also for her infant and other children (

40,

41). Potential benefits beyond clinical improvement for women with major depression and PTSD during the perinatal period might also include educational attainment, increased work productivity, improved social functioning, and positive child developmental outcomes, all of which are important considerations from a Medicaid perspective. In a recent study, we observed that compared with MSS-Plus, MOMCare led to better work and social functioning for depressed women with comorbid PTSD (

6). Our study, however, did not include observational measures of the mother-child relationship or a standardized assessment of child development. In making a strong argument for Medicaid expansion to cover perinatal depression care among high-risk women in Washington State, it is critical to incorporate these outcomes into future research.

Our findings are generally consistent with previous studies assessing the incremental benefits and costs of improving depression treatment in primary care in which most study patients were non-Hispanic white and covered by commercial or individually purchased health insurance (

24,

38,

42). To our knowledge, our incremental benefit-cost study is the first to extend examination to a public health setting serving pregnant, depressed, white women (41%) and women from racial and ethnic minority groups (59%) enrolled in Medicaid. Previous research suggests that the benefits of collaborative depression care may be greater for ethnically and racially diverse, economically disadvantaged, underserved patients, who are the most vulnerable in our society (

43,

44).

Our intervention lasted 18 months, by which time we assume that its clinical benefit completely disappeared. Our analysis of incremental costs took the perspective of the health plan or insurer, including Medicaid expansion. Other long-term studies have typically reported an increasing incremental benefit along with decreasing incremental costs with longer follow-up (

38,

45). As a result, insurers may expect to accomplish long-term clinical benefit after short-term investment in improved depression treatment.

These findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, self-report measures of mental health services may have overestimated costs (

38), although this bias would likely be equivalent across subgroups. Second, we could not distinguish the specific effects of either antidepressant medication or psychotherapy from the effects of contact with supportive obstetrics providers. Third, although the proportion of randomly assigned participants for whom outcome data were missing was relatively low, we cannot exclude the possibility of bias due to missing follow-up cost data. Those with missing and with complete clinical data did not differ in baseline demographic or clinical characteristics, and those with missing and with complete cost data did not differ in baseline depression severity or other demographic characteristics. However, those with partial cost data were more likely to have probable PTSD and to have been randomly assigned to MSS-Plus. Had we had complete cost data for the MSS-Plus group, we might have seen slightly higher costs as a result of greater depression severity with comorbid PTSD, which, in turn, would reduce the difference in costs between MOMCare and MSS-Plus, yielding a more notable finding. The converse is also a possibility, although less likely, given the pattern of results.

Conclusions

Ultimately, the primary goal of depression treatment is to relieve suffering and improve functioning, not to decrease health care costs. Our results offer some guidance to health care insurers and publicly funded health care programs contemplating efforts to improve perinatal depression care for socioeconomically disadvantaged women, particularly those with comorbid PTSD. According to a recent statement from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Maternal depression screening and treatment constitutes a critical role for Medicaid in the care of mothers and children” (

46). Our findings suggest that collaborative care for perinatal depression among women with probable major depression and PTSD has significant clinical benefit, with only a moderate increase in health services cost. Notably, collaborative care for perinatal depression delivered over 18 months was shown to cost about $2.50 a day, less than a short caffè latte. Considering the serious consequences of perinatal depression with comorbid PTSD for mother, baby, and family, it seems a small price to pay for such a critically important investment in depression care during pregnancy and the postpartum.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Theresa Hoeft, Ph.D., B.S., for her thoughtful reading of and suggestions for the manuscript. They also thank the study team for depression care management and other staff for assistance with recruiting, data collection and tracking, and administrative support. They acknowledge the leadership of the Maternity Support Services (MSS) of Seattle–King County Department of Public Health and MSS social workers, nurses, and nutritionists for their unfailing efforts in collaborating with the MOMCare team.