Unmet mental health needs disproportionately affect disadvantaged communities and underserved populations. Needy patients generally receive their health care in community health centers (CHCs) (

1). CHCs, also known as federally qualified health centers, are an important component of the primary health care safety net that promotes integrated care for both general medical and mental health conditions regardless of the patient’s ability to pay (

2,

3). The major role of CHCs is delivering comprehensive primary care that includes diagnostic screening, health education, and medication prescribing, although distinctions between mental health and general medical services are limited (

4). In recent years, considerable effort has focused on assessing and improving access to behavioral health services in these disadvantaged communities (

3,

5). Achieving this laudable goal, however, with relatively few mental health specialty providers in CHCs is challenging.

Medical staff who can diagnose, treat, and prescribe medications for mental health conditions in CHCs include physicians and advanced practice clinicians, such as nurse practitioners (NPs). NPs are a fast-growing group of health care professionals who are extensively employed in CHCs at twice the rate of their employment in private offices (

6–

8). Generally, NPs in CHCs are more involved than are other medical providers in patient health education, counseling, and preventive care (

9). NPs’ involvement in other types of services in CHCs, such as diagnosing illness or prescribing medications, will also likely be enhanced under the current regulatory trend toward the least restricted practice environment with independent practice authority (IPA) (

10). As of 2015, NPs in 17 states, including the District of Columbia, had NP-IPA, which allows them to independently diagnose, treat, and prescribe without any physician involvement. In the remaining 33 states, some level of physician involvement is required in NPs’ practice (

11).

Given the growing shortage of psychiatrists in the U.S. health care system, NPs may play a critical role in identifying and treating psychiatric symptoms of needy individuals in CHCs. However, studies comparing patterns of NP-provided mental health services according to level of state NP scope of practice are few. In one cross-sectional study of how the scope of practice influences NP labor markets, researchers found that states with a more restrictive scope of practice employed fewer NPs (

12). Another study found that Medicare patients in states with the least restrictive NP practice were 2.5 times more likely to receive primary care from NPs (

13). The least restrictive state NP regulations also were associated with increased NP staffing (

14), increased patient access to primary care services (

15), and more cost-effective treatment (

16). However, it is unclear whether the expanded NP scope of practice also affects the use of mental health services provided by NPs in CHCs.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether the expanded NP scope of practice is associated with the frequency of mental health visits to NPs in CHCs. It was hypothesized that CHCs in states with NP-IPA would likely have higher proportions of NP-related mental health service visits, compared with states without NP-IPA.

Methods

Data Source

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to inform ambulatory care delivered by office-based physicians who provide direct patient care (

17). The survey utilizes a multistage probability design accounting for primary sampling units (PSUs), provider practices within PSUs, and patient visits within the practices (

18). This cross-sectional study used data from a restricted access file of the NAMCS CHC stratum for calendar years 2006 through 2011. Annual survey response rate ranged from approximately 75% to 90% (

18). Typically, NAMCS includes too few CHC providers for reliable estimates to be obtained, but this restricted version of the NAMCS CHC stratum from 2006 to 2011 oversampled both advanced practice clinician and physician visits to improve the precision of CHC visit estimates, particularly estimates of visits provided by advance practice clinicians (

17).

According to the NCHS guidelines, estimates based on fewer than 30 observations are considered unreliable (

19). Thus we combined data across years (2006–2011) to ensure sufficient sample size within each provider subgroup. The study sample focused on 61,457 CHC visits, including NP visits (N=8,214) and physician-related visits (N=53,243). The excluded visits (N=4,408) were physician assistant–related visits that had too few visits in certain categories (below 30 observations) and visits in which the patient was seen only by other types of direct care providers (for example, registered nurses or licensed practical nurses). This study was deemed exempt from review by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Mental health–related visits.

CHC visits were divided into mental health–related visits and those not related to mental health. The visits with a mental health reason or a clinical diagnosis of a mental disorder were classified as mental health–related visits (

20). Other visits were grouped as non–mental health–related visits. Clinical diagnoses of mental disorders were identified by using the

ICD-9-CM. Visits with a clinical diagnosis of a mental disorder were grouped by the presence of mood, anxiety, disruptive behavior, substance use, schizophrenia, and other mental disorder diagnoses (

20). These were further divided into visits with and without recorded psychotropic medications. Psychotropic medication visits were identified according to the psychotropic drug classification adapted from Zito et al. (

21). Medication visits were grouped into the following categories: antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics-hypnotics, mood stabilizers (anticonvulsants and lithium), and other psychotropic medications (

21).

Provider type.

The type of health care provider was identified from two survey items in the NAMCS data: “What is the provider’s highest medical degree?” (provider level) and “Indicate all of the providers seen at this visit” (visit level). Medical doctors (M.D.s) and doctors of osteopathy (D.O.s) were categorized as physicians. The data included the provider weight to produce a national estimate by providers who saw patients during their reporting week (

17). We used the provider weight and the highest medical degree item to estimate the proportion of NPs and physicians in CHCs. The second item, covering all providers seen at the visit, was used to identify visits to NPs or physicians. Approximately 2% (N=143) of visits were provided by both an NP and a physician. We classified these into the NP group because the visits were assigned to patients whose main provider was an NP.

State NP regulation.

State NP practice regulations during the study period were obtained from previous reports: the Pearson report (

22–

24) and the annual legislative update (

25–

30). This information was merged with NAMCS CHC data. First, the state NP scope of practice was determined for each year between 2006 and 2011 as NP-IPA (defined as no physician involvement required for all three major activities: diagnosis, treatment, and prescribing) or no NP-IPA (meaning that some form of physician involvement was required for at least one of the three activities). Physician involvement included any legal requirement for physician supervision, collaboration, delegation, or consultation. The classification of the scope of NP practice was adapted from previous studies examining the impact of NP scope of practice (

12–

14). In this study, the classification used in previous studies was slightly modified by combining states with partial NP-IPA and states with no NP-IPA, because previous studies showed no substantial difference between partial and no NP-IPA (12,14). On the basis of this classification, 50 states and the District of Columbia were divided into three groups: states with consistent NP-IPA status throughout the study period (N=14; 13 states plus D.C.), states with no NP-IPA status throughout the study period (N=32), and states where NP regulations changed from no NP-IPA to NP-IPA status during the study period (N=5) (

Table 1).

Study Covariates

Patient demographic characteristics (age group, gender, race-ethnicity, and payment source), service type (new problem, chronic illness, or preventive service) and metropolitan statistical area were included in analytic models as covariates. The survey used the NCHS six urbanization categories based on the population density in the providers’ practice locations. Those include four metropolitan and two nonmetropolitan categories. The two nonmetropolitan categories were combined into one category labeled “nonmetro” in this study.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics and chi-square analysis were used to compare the sociodemographic characteristics of NP versus physician visits with any mental disorder diagnoses. We also analyzed the provider-level descriptive statistics (provider as the unit of analysis) to estimate the proportion of the CHC provider type that served as the main provider for patients with mental disorders according to NP-IPA status. The same descriptive analysis was performed to compare the proportion of NP versus physician visits with mental disorders and with psychotropic medications (visit as the unit of analysis).

To examine the association between NP scope of practice and CHC visits (mental health and non–mental health) by provider type, sets of multivariable logistic regressions were performed to estimate the odds of having NP-related visits in states with and without NP-IPA, with adjustment for age, gender, race-ethnicity, payment source, service type, and metropolitan statistical area. In these regression analyses, we excluded the five states in which state NP practice regulations changed from no NP-IPA to NP-IPA during the study period (N=3,261 visits). In all models, the dependent variable was visits by provider type (NP versus physician) and the main independent variable was NP-IPA status, with no NP-IPA as the reference group. Sampling design effects built on county, state, and region were incorporated into all of the analyses by using Taylor-series approximation with SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 10.0.1).

Results

Mental Health Visit Characteristics by Provider Type

Approximately 11% of the CHC visits were mental health related. Most mental health visits (90%) were provided by physicians. Among all physician-provided mental health visits, 92.6% were provided by primary care physicians and 5.4% were provided by psychiatrists. As shown in

Table 2, the characteristics of patients with mental disorders seen by NPs were significantly different from those of patients seen by physicians. A larger proportion of patients seen by NPs were female, from racial-ethnic minority groups, and between the ages of 18 and 64. NPs provided more visits related to new problems or preventive care, and physicians dealt with more chronic illness–related visits. NPs were more involved in visits covered by Medicaid, in self-pay visits, and in no-payment visits, and physicians handled a greater proportion of visits covered by private insurance. NP visits were clustered in nonmetropolitan areas compared with physician visits. No significant differences by region were found.

A higher proportion of NP visits were for substance use disorders (29.6% for NPs versus 11.0% for physicians; p<.001). Compared with physicians, NPs handled a smaller proportion of visits for disruptive behavior disorder (19.1% versus 9.3%; p=.03) and for anxiety disorders (24.6% versus 16.3%; p=.02). No significant differences between NP and physician visits were noted by psychotropic drug class, except for antidepressants. Antidepressants were provided by NPs at a greater proportion of visits, compared with physicians (70.4% versus 61.6%; p=.03). [These and other findings by disorder and by medication class are presented in an online supplement to this article.]

CHC Visits by NP-IPA Status

As shown in

Table 3, the odds that a mental health-related visit was provided by an NP were more than two times greater in CHCs located in states with NP-IPA, compared with states with no NP-IPA (adjusted odds ratio [OR]= 2.43, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.12–4.60). In contrast, non–mental health–related visits provided by NPs did not significantly differ by states’ NP-IPA status (adjusted OR=1.45, CI=.87–2.34).

Among all mental health–related visits in CHCs, the odds of visits with psychotropic medications prescribed by an NP were more than three times greater in states with NP-IPA status than in states without NP-IPA status (adjusted OR=3.14) (

Table 4). Consistent with the visit-level estimation (

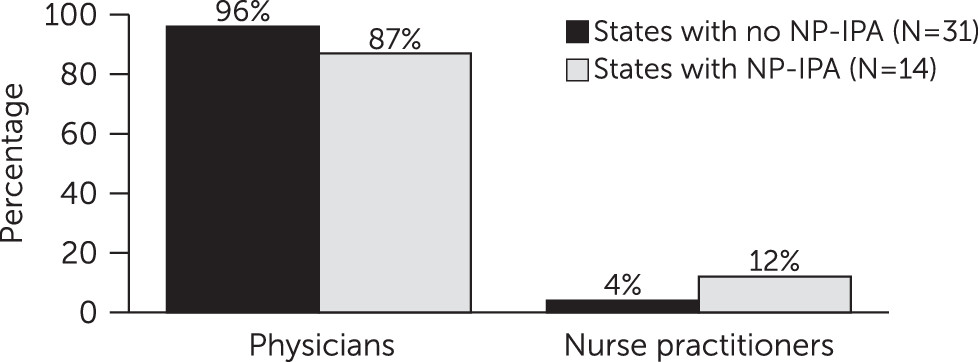

Tables 3 and

4), the provider-level estimation indicated that the proportion of NPs who treated patients with mental disorders was significantly greater in states with NP-IPA compared with states with no NP-IPA (12% versus 4%, respectively) (

Figure 1).

Discussion

This study provides new information on the growing role of NPs in providing mental health services in CHCs, specifically in states with NP-IPA. The study found that the proportion of mental health–related visits provided by NPs in CHCs was more than two times greater in CHCs located in states with NP-IPA, compared with states with no NP-IPA. Specifically, psychotropic medication–related visits provided by NPs for patients with mental disorders were more than three times greater in states with NP-IPA than in those with no NP-IPA. Compared with physicians, NPs who provided visits for mental disorders in CHCs had a proportionally greater involvement in visits covered by Medicaid, involving new problems and preventive care, made by patients from racial-ethnic minority groups, and occurring in nonmetropolitan areas. NPs were also more involved than were physicians in visits by patients with substance use disorders and in visits at which antidepressants were prescribed. NP involvement in visits involving anxiety disorder or disruptive behavior disorder was proportionally lower than that of physicians.

Characteristics of Mental Health–Related Visits Provided by NPs Versus Physicians

Compared with physicians, NPs provided proportionally more mental health–related visits for patients from racial-ethnic minority groups and for Medicaid enrollees. Similarly, Buerhaus and colleagues (

31) reported that compared with primary care physicians, primary care NPs were more likely to serve underserved populations, particularly Medicaid enrollees, in a wide range of community settings. An increased reliance on NP-provided services in rural areas has also been well documented in previous reports (

32,

33). Given persistent problems with the availability of accessible and efficient mental health care in rural areas, granting NP-IPA may be one of the solutions to accommodate unmet mental health care needs among persons residing in these communities. We also found that NPs provided a higher proportion of new or preventive care visits, compared with physicians, and that physicians provided more visits for chronic illness care. This could indicate that visits provided by NPs were more common for new patients as a way to shorten their waiting time to see a physician. NPs may then have referred patients with more complex problems (such as chronic mental disorders) to physicians.

One significant finding concerns NPs’ greater involvement in treating substance use disorders in CHCs. A national survey noted that a risk assessment, including substance use behaviors and life-threatening physical conditions, was the second most critical work activity of NPs (

34).

Effect of NP-IPA in Mental Health Services

The adoption of NP-IPA had a significant positive association with the proportion of NP-provided mental health–related visits but not with the proportion of NP-provided nonmental health–related visits. This finding suggests that the role of NP-IPA during the study period (2006–2011) may have been specific to a particular practice area in which NPs’ scope of practice had been most restricted, such as in prescribing controlled psychotropic medications—for example, benzodiazepines or stimulants. This could presumably be related to concerns about access to substances with a potential for abuse. A possible factor influencing NP-IPA status is the geographic maldistribution of psychiatrists across the United States, particularly in states with NP-IPA. According to a map that shows where shortages of mental health specialists exist (

35), states in which there is more unmet need for mental health care greatly overlap states with NP-IPA. In states with NP-IPA, patients with unmet need for mental health care in areas with limited mental health care resources (for example, few psychiatrists) may utilize CHCs for initial or ongoing mental health treatments provided by NPs. In addition, patients with limited income or no insurance may prefer access to treatments in CHCs because of possible stigma related to using a community mental health center or simply because the patients do not recognize their need for mental health services. Thus the need for mental health services may be identified in the course of medical care.

Among visits involving patients with mental disorders, a strong association between a state’s NP-IPA status and NP-prescribed psychotropic medication–related visits was particularly notable. In states with NP-IPA, the odds of NP-prescribed psychotropic medication–related visits were significantly higher than in states with no NP-IPA, which may be a result of NPs’ ability to practice independently or of the increased number of NPs in the workforce. When this finding was examined further by using provider-level estimation, a greater number of NPs provided visits related to mental disorders in states with NP-IPA than in states without NP-IPA (

Figure 1). Indeed, the scope of practice affected both the practice ability of NPs and the supply of NPs (

12).

CHC patients, who are mostly from medically underserved communities, may have substantially more mental health care needs than patients in other low-income U.S. populations (

36). It appears that NPs in CHCs are in a critical position to identify mental health problems and help patients with unmet mental health care needs initiate and participate in mental health services. This role will likely be enhanced in practice environments where NP-IPA is granted. NP-IPA competency in psychotropic medication prescribing, their use of referral sources, and their educational needs should be periodically examined (

37). Although psychiatric NPs receive specialty training in mental health, the current nonpsychiatric NP educational curriculum does not include comprehensive mental health specialty training. If possible, continuing education focusing on mental health and substance abuse treatments, psychopharmacology guidelines, and monitoring should be offered to both psychiatric NPs and nonpsychiatric NPs working in CHCs, so that all NPs will be optimally prepared to address this growing health care service need.

Study Limitations

The findings should be interpreted in the context of limitations. Findings are limited to visits in U.S. CHCs and thus may not be applicable to other ambulatory care settings, such as private offices. Second, because the NAMCS data were structured to produce visit-level estimation, it is possible that some patient duplication occurred, making it difficult to estimate the number of people with various mental disorders who were treated in CHCs. Third, the provider specialty of both NPs and physicians could not be identified because of unstable estimates of psychiatrist-provided visits (too few psychiatrists in CHCs) and missing information on NP specialty in the data. Fourth, unknown state variations and secular trends related to provider practice and psychotropic medication prescribing during the study period could have confounded the NP comparison between states with and without NP-IPA. Despite these limitations, our findings provide valuable insight into the role of state NP regulations from a national perspective. Use of the NAMCS CHC stratum data is the greatest strength of this study, because, to our knowledge, this is the only database in which the practice of NPs and physicians in CHCs can be compared at a national level. The NAMCS data are also known to have high accuracy in terms of clinician-reported diagnosis and linkage to the prescribed medication data (

17).

Conclusions

This study provides new evidence about the role of state NP-IPA in relation to expanded mental health services delivered by NPs in CHCs. The findings highlight NPs’ contribution to mental health service delivery according to NP-IPA status. The profound growth in the number of NPs in the United States (

38) and their increasing professional autonomy document major ongoing changes for mental health service delivery in CHCs. Additional studies focusing on the quality of mental health care provided by NPs under NP-IPA in community health care settings are warranted.