Efficacious psychopharmacological treatments for a wide variety of mental disorders have been identified (

1). Clinicians are increasingly aware of these treatments to deliver the most effective services to their patients. However, patient participation, engagement, and adherence to treatment regimens are essential components of effective treatment. A number of studies show that medical outcomes are poorer when patients receive an inadequate dose of treatment (

2). Patient nonadherence to medication is a significant problem throughout clinical medicine (

3,

4). Treatment adherence is even more problematic in psychiatric populations because mental health impairments lead to poor insight, reasoning difficulties, and low motivation to comply with treatment regimens (

5). Therefore, to improve medication adherence and maximize the likelihood of achieving desirable outcomes, research should focus on identifying factors associated with increasing patient engagement and participation in treatment.

A number of studies examining patient-provider interactions have been conducted in the fields of medical and psychotherapy treatment. For example, in studies of both general and specialty medical practitioners (including family medicine, internal medicine, and oncology), a positive physician-patient relationship and physician-patient communication have been moderately correlated with a variety of health outcomes, including decreased psychiatric symptoms, resolution of general medical symptoms, improved functional status, decreased blood pressure, improved blood sugar levels, and better pain control (

6,

7). Similarly, in the psychotherapy treatment literature, the therapeutic relationship or alliance has been found to be one of the most robust predictors of adult and youth mental health treatment outcomes across various psychotherapy approaches (

8,

9).

Clearly, variables related to the therapeutic relationship are important components in many psychotherapeutic and general medical approaches with diverse patient populations. The therapeutic alliance may also be important for patients who receive psychopharmacological services for a wide variety of mental health issues. In fact, the therapeutic relationship may be more important for psychiatry than for general medicine. The effectiveness of psychopharmacological treatment requires taking medications outside the treatment session, and the role of the therapeutic relationship may be critical in this regard. Some psychiatric medications take time before a therapeutic effect is evident, and many have side effects (

10). Because adult patients are usually responsible for their medication compliance, alliance development seems a particularly relevant factor for managing effectiveness expectations and side effects that could mitigate adherence.

A strong therapeutic relationship may therefore encourage patient willingness to continue medication use despite unpleasant side effects or the lack of immediate therapeutic effect. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis of the association between the therapeutic relationship and psychopharmacological treatment outcomes among adult psychiatric patients. On the basis of previous studies, we expected to find a significant relationship between the therapeutic relationship and treatment outcome variables.

Methods

Search Strategy

The literature search included PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, publication alerts from Ingenta, and Web of Science–Science Citation Index databases. Combinations of the following search terms were used: therapeutic relationship, therapy relationship, treatment relationship, relationship, patient, physician, psychiatrist, psychiatry, behavior, empathy, interaction, patient perception, communication, and alliance. Authors of relevant articles were searched in the aforementioned databases to determine whether they had published additional research, and the reference lists of found articles were searched for any studies not returned by the literature search. Finally, Google Scholar was used to search for studies that may have been harder to find with the standard databases and for unpublished manuscripts. Published journal articles or dissertations written in or translated into English until February 2014 were included. The search yielded 296 results.

Study Inclusion Criteria

The meta-analysis used the following inclusion criteria: empirically based studies examining the therapeutic relationship (that is, measures were administered explicitly assessing the therapeutic alliance or relationship) and examining the association between the alliance measure and physician-related medication management outcomes for adult patients.

In cases in which abstracts provided insufficient information to adequately assess eligibility, the full article was reviewed to avoid elimination of appropriate articles. Nine articles that met criteria were retained. [A flow diagram of study selection is presented in an online supplement to this article.] Two of these articles used data from the same study, and only one effect size was then computed. Therefore, eight studies were included in the final meta-analysis, with 59 samples of data across multiple alliance and treatment measures.

Data Extraction

Data entry used a standardized form. For each of the eight studies, the following information was coded: author, publication year, relationship variables, outcome variables, number of patients, patient age, type of prescribing health professional, sample size, and relationship to outcome effect size. Two independent raters (CMWT and SAF) coded each study. One of the authors (MK) discussed coding discrepancies with each rater, and all were resolved through repeated review until consensus was reached.

Statistical Analysis

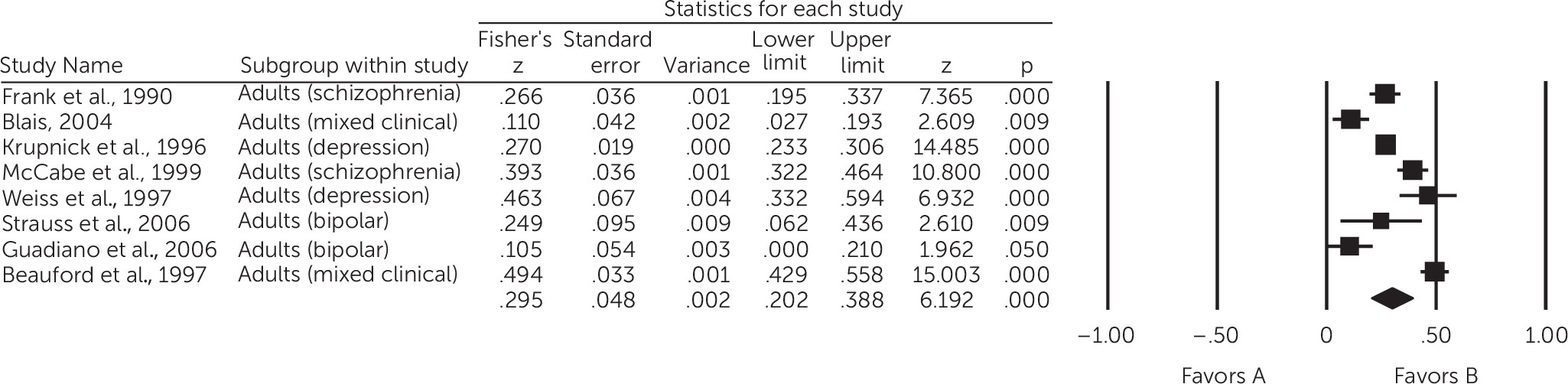

Fisher’s z was computed for small sample size by using the statistical software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, Version 2 (

11). Means and standard deviations (SDs) or correlations were preferred to compute effect sizes. When correlations were used, Fisher’s z was calculated from r. In the one other case, mean and SD values were used to calculate Fisher’s z. Positive z values indicate better outcomes as a function of increased alliance. All eight studies included sufficient information to calculate effect size. If a study employed more than one measure of alliance or outcome, involved different conditions and did not supply an overall effect, or involved distinct groups, then individual effect sizes were calculated and averaged to provide an overall effect size for the study. For studies reporting a nonsignificant relationship between alliance and outcome, the effect size was conservatively imputed to be zero. Inverse relationships were entered as negative values. Fifty-nine individual effect sizes were calculated across measures, samples, and conditions, which were pooled to provide a composite effect size per study, or eight overall effect sizes weighted by sample size. Cochran’s Q homogeneity statistic was used to determine whether a random or fixed-effects model would be required. We intended to examine potential moderators of the association between the therapeutic relationship and outcome (

9), but we had too few studies to adequately power an analysis.

Meta-analysis typically involves accounting for publication bias (that is, studies with nonsignificant results are less likely to be published) (

12). Two approaches examined publication bias: funnel plot (Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill [

13]) and fail-safe N (that is, the number of additional “negative” studies [with a zero intervention effect] needed to increase the p value above .05 [

14]).

Discussion

This first meta-analytic review examining the therapeutic relationship in psychiatric medication management indicated that a higher-quality physician-patient relationship was related to better mental health treatment outcomes. Across eight empirical studies, the average effect size was z=.30, a medium effect size commensurate with that found in the literature on the therapeutic alliance or relationship in adult and child psychotherapy (

8,

28–

30). The findings suggest that the therapeutic alliance is just as important in pharmacotherapy adherence as it is in psychotherapy participation. In addition, the effect size suggests that there is considerable variability in the association between the therapeutic relationship and the success of psychiatric medication management. Many physicians form high-quality relationships with their patients, resulting in positive outcomes; however, many relationships need improvement, given the less-than-optimal treatment outcomes in some studies.

Successful psychopharmacological treatment relies on patients’ adherence to prescribed medications (

31–

34). Considering that research has suggested that the therapeutic alliance predicts outcomes across various clinicians and therapies (

8), it should not be surprising that it is also important in facilitating positive medication management outcomes, in particular with psychiatric patients (

35–

37). The results of this meta-analysis suggest a possible mechanism—namely, that a strong physician-patient alliance contributes to improved medication adherence, which may result in positive treatment outcomes. Because the meta-analysis did not assess medication adherence, future research should examine whether medication adherence mediates the relationship between alliance and treatment outcomes or whether the alliance has a more direct curative effect. An alternative possibility is that other unmeasured variables related to the therapeutic alliance may be the actual mechanisms. Specific physician behaviors, such as providing acknowledgment and support (

38) or a credible rationale for medication use (

39), may be directly related to treatment adherence or outcome, but such behaviors may also result in patients’ experiencing positive feelings toward their treating physician. Other understudied variables that may be related to the association between therapeutic alliance and positive treatment outcomes include treatment dose (length of sessions), time between sessions, early symptom change, patient empowerment in managing his or her psychiatric illness, patient motivation to change, or even organizational or agency factors (for example, warmth of the physician’s administrative staff). In addition, development of attachments and empathy (

40), patient misunderstanding or forgetting prescription instructions, economic barriers or barriers related to the family or the environment, failure to remember to take medications consistently, and regular physician assessment of adherence may also contribute to medication adherence (

41).

Given the significant relationship between the therapeutic alliance and outcomes found in a very small sample of studies, each study was carefully examined for limitations in methodological quality. First, the studies used diverse measures to assess alliance, and most did not focus exclusively on the relationship between alliance and outcome in medication management. Several studies included physicians who delivered both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (

20,

22,

23), some studies combined data from individuals who were receiving only psychotherapy with data from those also receiving pharmacotherapy (

16), others focused on physicians delivering only medication management (

15), and others reported alliance ratings for a treatment team, which included a prescribing psychiatrist (

16,

17,

20–

23). Thus it was difficult to determine what aspects of the alliance were associated with favorable relationships and whether alliance in the context of psychotherapy or psychopharmacology with the psychiatrist or physician was responsible for treatment effects. However, the effect size found is consistent with that in the psychotherapy literature. If the studies had included only measures of the alliance in pharmacological treatment, the relationship between the alliance and medication management outcomes might have been stronger.

In addition, methodological issues might explain why two of the studies demonstrated weaker associations between alliance and outcomes (

15,

23). In the study by Blais (

23), the aggregation of the alliance construct across the perspectives of multiple informants and helping professionals may have diluted the study’s ability to identify a stronger alliance-to-outcome effect size. Moreover, study effect sizes may have been attenuated as a result of the long time lag between assessment of the alliance and of discharge outcomes. In studies with long treatment duration, it might be more effective to assess patterns of alliance over time. This is an area for future research. Furthermore, the effects were stronger for the relationship between the alliance and change in depression symptoms, compared with symptoms of mania, and for the relationship between the alliance and change in overall functioning scores. Additional studies are needed to provide adequate power to assess moderating effects such as these.

Many studies also did not provide information on the physicians or on the number of physicians in the study. The alliance measures used in the studies also varied extensively. The Working Alliance Inventory was the most frequently used, but it was used in only two studies. This raises the question of whether each study measured the same construct. However, the consistently significant findings across studies suggest that each measured the same alliance construct. Furthermore, sample heterogeneity existed in the eight studies. However, the consistent results suggest the importance of the relationship between alliance and outcome despite the diversity in samples and measures. Unfortunately, the small number of studies did not allow for moderator analyses to examine patterns attributable to theoretical or methodological issues. For example, alliances may have more or less impact depending on the problem or diagnosis treated, the outcome examined (which varied across studies), the alliance measures used, and the treatment settings (inpatient versus outpatient). Although this meta-analysis included a small sample of relevant work, the findings provide justification for more research in this area. Furthermore, some findings may have been inflated because of shared method variance or temporal similarity (in some studies, alliance measures were completed at the same time as outcome measures [

15,

16,

20,

23]). Variability in timing of alliance ratings may have had an impact on effect sizes. Alliance assessments in middle to late treatment may have inflated the relationship between alliance and outcomes, especially if the alliance assessments occurred after patients began experiencing potential improvements.

Despite some limitations, three studies were the most methodologically sound of those reviewed, with the clearest evidence of a moderate relation (average r=.26) between the therapeutic relationship and psychiatric medication management (

15,

18,

19). Higher-quality studies should be conducted to further elucidate outcomes.

The aforementioned limitations indicate several areas for future research. There is a need for more studies of psychiatrists across levels of experience, of clinicians delivering only pharmacotherapy, and in outpatient settings. The literature would benefit from studies focusing on medication management for a variety of patients (for example, various diagnoses and stages of development) who are typically seen for brief appointments. If the alliance is found to serve a truly important role in pharmacotherapy, then research should examine its mechanisms in medication management and whether they vary depending on the characteristics of the patients being treated or the type of medication prescribed. Moreover, psychotherapy alliance measures have been developed on the basis of certain assumptions, such as one-hour therapy sessions, weekly meetings, and treatment success as assessed by conversations between the therapist and the patient. Given that these assumptions do not typically apply to medication management, treatment process measures are needed that reflect treatment considerations in psychiatric practice (such as brief appointments rather than weekly meetings and not considering physician-patient conversations as the primary treatment ingredient). Finally, we conducted a thorough review of existing research and noted a lack of studies focused exclusively on the alliance-outcomes relationship in pharmacotherapy, which suggests a major gap in the literature on the therapeutic alliance that needs to be addressed.