Over the past two decades, the increased prevalence of pediatric antipsychotic medication use (

1) has generated safety concerns (

2,

3), particularly in light of insufficient evidence to support the off-label use of antipsychotics for behavioral disorders and aggression in the pediatric population (

4). The concerns have been most prominent for second-generation antipsychotics and feature increased weight gain (

5) and metabolic abnormalities and diabetes secondary to antipsychotic use (

6,

7). Public-sector policy responses that promote peer review of requests by clinicians for antipsychotic treatment for children in state Medicaid programs have been particularly prominent (

8). Assessment of the impact of Medicaid peer-review programs varies with state criteria and pediatric age group (

9,

10).

The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene implemented a three-phase antipsychotic peer-review program beginning in October 2011. The implementation was sequential according to age group: phase 1 included children ages zero to four (October 2011), phase 2 added those ages five to nine (July 2012), and the final phase expanded to those ages 10 to 17 (January 2014). In the first stage of the review process, clinical pharmacists at the partnering academic center review requests for new prescriptions and refill prescriptions of antipsychotic medications on the basis of prespecified clinical criteria that identify the child’s age, psychiatric diagnosis, target symptom severity and functioning, psychosocial service use, medication dosage and regimen based on the child’s weight and age, and monitoring criteria (for example, laboratory glucose and lipid levels) (

11). If a prescription request is denied, the prescriber may pursue a secondary review involving a dialogue with a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the academic center’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department (

11). Overall, each antipsychotic prescription (new or refill) for children 17 and younger is reviewed for monitoring criteria, and authorization is limited to the approved period, which can vary with indication, severity, age, and laboratory monitoring. [More details on the clinical criteria are presented in an

online supplement to this article.]

Published evaluations of the impact of peer-review authorization programs are sparse, and findings are mixed (

8–

10). In addition, interstate research designs allow for comparisons between states to assess the differences in program implementation and their possible effects on practice change (

9). To better understand the impact of antipsychotic prescribing pattern changes, we assessed off-label prescribing and physician specialty before and after policy implementation. Also, to gauge the extent to which other psychotropic medication classes may have been adopted as substitutes for antipsychotics in the postimplementation period, we assessed the pre-post prevalence of use of other leading psychotropic medication classes.

Methods

Data Sources

We analyzed computerized data from Medicaid administrative claims for the 12 months before and after October 2011, July 2012, and January 2014 in a mid-Atlantic state. Using encrypted enrollee identification numbers, we linked Medicaid enrollment files, outpatient hospital clinic and physician files, and prescription drug files. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland, Baltimore, Institutional Review Board.

Study Design

In a cross-sectional design, data were analyzed for continuously enrolled youths in the 12 months before and after each of the three age-specific policy implementation phases to create three pairs of cohorts. In the first pair, we identified children ages zero to four who were continuously enrolled from October 2010 to September 2011 (preimplementation) (N=118,815) and from October 2011 to September 2012 (postimplementation) (N=121,431). In the second pair, we identified children ages five to nine who were continuously enrolled from July 2011 to June 2012 (preimplementation) (N=98,681) and from July 2012 to June 2013 (postimplementation) (N=107,872). Last, we identified those ages 10 to 17 who were continuously enrolled from January 2013 to December 2013 (preimplementation) (N=154,696) and from January 2014 to December 2014 (postimplementation) (N=161,370). In each age category, we compared demographic and administrative characteristics in the pre- and postimplementation periods. All age ranges expressed in this article are inclusive of the final number.

Study Variables

Antipsychotic and other psychotropic medication class use.

In each age category, we assessed total (first- or second-generation) antipsychotic medication dispensings by linking enrollment files and prescription drug files. We assessed antipsychotic medications available in the United States between 2010 and 2014. More than 90% of antipsychotic dispensings were for second-generation antipsychotics.

To assess antipsychotic off-label use, we identified year-specific, age-specific Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved indications for first- and second-generation antipsychotics from the categorization of Christian and colleagues (

12). [A figure in the

online supplement lists approved antipsychotics by disorder and age.] Similarly, we assessed dispensings of the five leading psychotropic medication classes (antidepressants, stimulants, alpha-agonists, anxiolytics-hypnotics, and anticonvulsants–mood stabilizers) according to age categories in the pre- and postimplementation periods.

Psychiatric diagnoses.

Clinician-reported psychiatric diagnoses were identified from outpatient and physician files by using

ICD-9-CM codes [see

online supplement for list]. At least two physician claims on separate days were required to qualify for a psychiatric diagnostic category (

13). Psychiatric comorbidities were common in these data. Consequently, we adopted a hierarchical approach to classify individuals only once on the basis of their most severe or functionally impairing condition (

14). Because antipsychotics are used in a wide range of pediatric conditions, many of them off label, we aimed to identify mental and developmental conditions in a rank order from most to least severe and impairing across the range of psychiatric diagnoses (

1). To ensure sufficient sample size, we initially grouped psychiatric diagnostic groups among antipsychotic users as follows: schizophrenia, autism–pervasive developmental disorders, intellectual disability, bipolar disorder, disruptive disorders and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, other psychiatric disorders (depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders, and communication and learning disorders), and no recorded psychiatric diagnosis.

Physician specialty.

For each antipsychotic prescription dispensed, we matched the prescribing clinician’s national provider identifier from medication claims with provider specialty codes derived from a statewide database. For each antipsychotic dispensing, we reclassified prescriber specialty into psychiatry, primary care (pediatrics, general medicine, and family medicine), other specialties, and missing specialty.

Study covariates.

Study covariates included Medicaid eligibility category, gender, race-ethnicity (white, African American, Hispanic, and other), and region of enrollee’s residence (metro region 1, metro region 2, and other counties). Medicaid eligibility category included youths in foster care, youths with disabilities who qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and youths eligible for Medicaid coverage because of family income at or below the federal poverty level—that is, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)—or family income ≥200%−300% above the federal poverty level—that is, State Children’s Health Insurance Plan (SCHIP). Among youths who were eligible for Medicaid in multiple categories in a given year, we assigned eligibility category on the basis of a hierarchical approach beginning with any month of foster care enrollment and subsequently by those with any month of SSI, SCHIP, and TANF enrollment.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted at either the person level or prescription dispensing level with SAS, version 9.3. At the person level, the primary outcome measure was annual prevalence of age-specific antipsychotic medication use, calculated as any use (one or more dispensings) in a specific age group, expressed as a percentage of eligible enrollees in that age group in the pre- and postimplementation periods.

We conducted age-specific multivariable logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations to examine antipsychotic medication use before and after the program implementation, adjusted for study covariates. In addition, to evaluate the possible substitution of other psychotropic medications for antipsychotics following policy implementation, we assessed the annual percentage prevalence of other leading psychotropic medication classes before and after policy implementation.

At the prescription-dispensing level of analysis, we estimated the proportion of antipsychotic dispensings that did not meet the FDA-approved age- and disorder-specific indications. In addition, we assessed the proportion of antipsychotic dispensings from psychiatrists, primary care physicians, or other clinician specialties (for example, physician assistants and nurse practitioners) for the zero-to-four and five-to-17 age groups before and after policy implementation.

Results

Data on the peer-review authorization of antipsychotic dispensings indicated an overall reduction in the proportion of antipsychotic-medicated youths (regardless of age group) of 30.4% (from 5.6% to 3.9%, pre- to postimplementation of the policy [data not shown]).

Table 1 shows the age-specific prevalence of antipsychotic use for each age group in the pre- and postimplementation periods. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) indicate significant reductions in use in the postimplementation versus the preimplementation period. However, the extent of reduced use varied by age group: ages zero to four, AOR=.41; ages five to nine, AOR=.54; ages 10 to 17, AOR=.72.

Data on five other psychotropic medication classes are presented to gauge the extent to which other classes may have been adopted as substitutes for antipsychotics (

Table 2). Overall, no significant change was noted in the use of the five leading psychotropic classes among children ages zero to four (AOR=1.10, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.99–1.21), while there were marginally significant differences among 10- to 17-year-olds (AOR=1.02, CI=1.01–1.03). Among children ages zero to four, the single exception was alpha-agonist use, which increased in the postimplementation period (AOR=1.30). By contrast, use of other psychotropic medications decreased among those ages five to nine (AOR=.73, CI=.71–.74).

We ruled out population differences that might influence changes in prescribing patterns by evaluating characteristics in terms of gender, race-ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility category, and enrollees’ region of residence in the pre- and postimplementation periods (

Table 3). The proportions of males and females did not differ across the age groups pre- and postimplementation. African Americans were the largest racial-ethnic group in all age groups, and this was unchanged following the implementation of policy restrictions. Most enrollees (≥60% for all age groups) were eligible for Medicaid because of family income at or below the federal poverty level (TANF).

Table 3 shows that the pre-post populations were quite similar regardless of age group.

Diagnostic Patterns

Behavioral disorders were the most prominent clinician-reported diagnoses among antipsychotic users (ages zero to four, 52.9%; ages five to nine, 68.4%; and ages 10 to 17, 43.4%), with slight decreases in the postimplementation period (

Table 4). In the preimplementation period, serious and impairing psychiatric diagnoses consisted primarily of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism, ranging from a low of 21% among children ages five to nine to a high of 29% among those ages 10 to 17. The distribution of diagnoses in the postimplementation period was similar. Clinician-reported diagnoses of mental disorders other than severe and impairing psychiatric disorders and behavioral disorders were less than 10% among children less than 10 years old and 19% among those ages 10 to 17.

Off-Label Antipsychotic Use

We analyzed total antipsychotic prescriptions dispensed according to FDA-approved indications by age group and found a slight reduction in off-label use for children ages five to nine (88.4% preimplementation to 85.7% postimplementation) and those ages 10 to 17 (74.2% to 71.8%). All use of antipsychotics among children ages zero to four reflected off-label use. Overall, the data showed modest proportions of use for labeled indications, underscoring widespread pediatric off-label antipsychotic use.

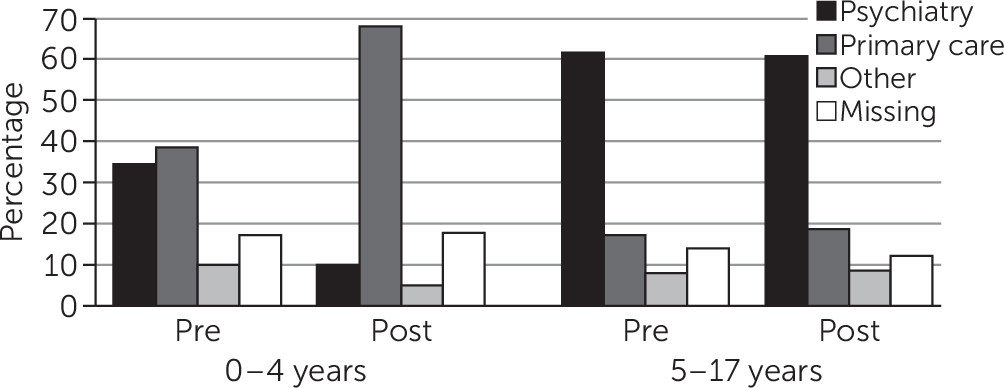

Prescriber Specialty

Figure 1 shows the distribution of dispensed prescriptions for antipsychotics in the pre- and postimplementation periods by prescriber specialty. Among children ages zero to four, a substantial drop was seen in psychiatrist-ordered antipsychotics and a proportional increase in antipsychotics ordered by primary care physicians. By contrast, the change in the distribution by prescriber specialty among older youths (ages five to 17) was negligible.

Discussion

The main finding of this study indicates that the state requirement of peer-review authorization of antipsychotic prescribing for Medicaid-insured children had a substantial impact. The prevalence of pediatric antipsychotic use among Medicaid-insured youths decreased significantly in the 12 months following each age-specific peer-review policy implementation. No evidence was found that alternative psychotropic classes were used as substitutes for antipsychotics, with the possible exception of alpha-agonist use among children ages zero to four. The clinical literature on aggression discusses a range of pharmacological classes, including alpha-agonists, as alternatives to antipsychotics (

15,

16). However, additional evidence of benefits is needed (

17).

Our 12-month assessment of the impact of this age-specific, sequential peer-review program showed a 30.4% decrease (from 5.6% to 3.9%) in antipsychotic users across the age groups (ages zero to 17 years). The finding is consistent with the 49% drop (from .51% to .25%) in antipsychotic users (ages zero to 17) from a similar peer-review authorization program in Washington State (

10). By contrast, an impact study conducted in an adjacent mid-Atlantic state (state A) showed slightly reduced use of antipsychotics among children ages six to 12 (9.8% to 9.5%) and those ages 13–17 (11.3% to 11.1%) and an increase in antipsychotic use among children ages zero to five (1.7% to 2.1%) (

9). Notably, pediatric antipsychotic use in the study reported here and in state A showed prevalence of use that is an order of magnitude greater than in Washington State—a regional variation that demands further exploration through population-based clinical research.

Analyzing data among Medicaid-insured children ages zero to five in Florida, Constantine and colleagues (

18) found a 35% decrease in requests for approval of antipsychotic use, which presumably reduced the prevalence of antipsychotic use. However, published studies reflect research designs that are not directly comparable to our analysis, thus limiting comparisons of our findings (

9,

10,

18).

Impact study designs are complex methodologically and present challenges in terms of their clinical implications. For example, one study employed a triple-difference strategy to reduce threats to validity in examining the impact of prior authorization of antipsychotics, featuring differences between two states, differences within each state (between antipsychotics and an alternative psychotropic medication class), and differences in antipsychotic use in pre-post periods (

9). Comparison with a neighboring state has both benefits and risks. In the two-state comparison, state B without a peer-review policy was compared with the adjacent target state (state A), which introduced a peer-review policy in 2008. One aspect of this between-state comparison worth noting is the baseline difference in the prevalence of antipsychotic use. For example, compared with state A, state B had lower use of antipsychotics in all age groups: ages zero to five, 2.7 times lower; ages six to 12, 1.5 times lower; ages 13–17, 1.7 times lower. These baseline differences made comparisons of short-term change problematic. In addition to baseline prevalence differences in adjacent states, states have differences in formularies, patient populations, and prescriber training and experience—factors that might influence the use of antipsychotics, particularly for off-label indications. Collectively, the impact studies reviewed here (including this study) suggest that future research could benefit from a standardized approach to assess impact.

Critically important to the outcome of antipsychotic review programs is the nature of the program that is implemented. Overall, the peer-review program in this study requires prescribers to provide reviewers with the patient’s demographic information, indication for treatment, antipsychotic medication prescribed, history of psychosocial service use, weight, height, fasting laboratory results, and electrocardiography recordings for ziprasidone or quetiapine use [see

online supplement]. The model created by Washington State was innovative in strategizing for a partnership access telephone line to encourage building relationships between academic psychiatrists and primary care prescribing physicians. Beginning in 2008 with a voluntary telephone access program and advancing to a mandatory program in 2009, the program at its core is educational and emphasizes partnering across specialties to ensure high-quality care (

19).

Two ancillary topics we addressed in this study are related to antipsychotic prescriber specialty and off-label use (

20). The specialty of antipsychotic prescribers differed significantly for children ages zero to four from the pre- to the postimplementation period (

Figure 1) and likely reflects the relatively smaller proportion of psychiatrists who treat very young children. Our data indicated that all antipsychotic use among children ages zero to four was off label and the majority of antipsychotic use among five- to nine-year-olds (88.4%) and 10- to 17-year-olds (74.2%) was off label. Not surprisingly, there was virtually no age-specific change in off-label use pre- to postimplementation of the peer-review program. More important is the continuing critical need for assessment of benefits and harms of antipsychotics for behavioral disorders and aggression in large pragmatic clinical trial designs (

21) and in postmarketing cohort studies (

22).

Clinical practice implications of these findings include the need to improve baseline and follow-up monitoring of health status when pediatric antipsychotic treatment is initiated (

23,

24).

Several limitations of the study are worth noting. First, findings from this impact study may not be generalizable to other state Medicaid peer-review programs because only one state program was assessed. Because the design and implementation of Medicaid prior-authorization programs vary from state to state, a side-by-side comparison of programs between states is impractical. We examined one-year pre- and postimplementation periods to assess near-term impact. However, subgroup analyses of data with longer review periods have shown that rates of use of antipsychotics may stabilize while rates for other psychotropic classes may increase, particularly for concomitant use (

25,

26). Second, causal inferences about the impact of peer review may be challenged. For example, a mandatory Web-based antipsychotic registry in North Carolina (without peer review) had preliminary data after six months indicating that antipsychotic prescribing decreased (

27). Regardless of the antipsychotic monitoring program approach, such oversight programs would benefit from research on clinical symptom and functional outcomes—for example, parent satisfaction with behavior control and school attendance data. Third, diagnostic groups were derived from the

ICD-9-CM clinician-reported claims for reimbursement and did not have the reliability of research-assessed diagnoses. To increase the validity of clinician-reported diagnoses, we required that each diagnosis be confirmed by more than one claim on different days in the 12-month period (

13). In addition, a hierarchical algorithm of psychiatric disorders according to severity and functional impairment of conditions was used to classify diagnoses in relation to antipsychotic medication use.