Discussion

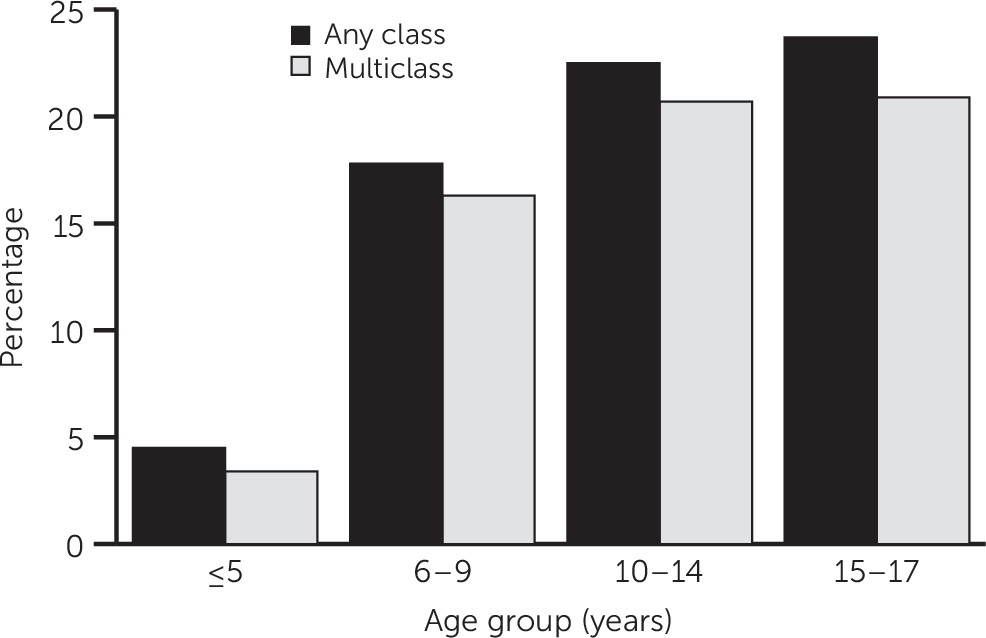

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the prevalence of psychotropic polypharmacy among pediatric Medicaid enrollees over a span of 10 years. First, the prevalence of any-class and multiclass psychotropic polypharmacy among children who received at least one psychotropic medication increased steadily. Second, at the end of the study period, more than one-quarter of youths who were using at least one psychotropic received a psychotropic polypharmacy regimen. Third, psychotropic polypharmacy increased consistently with age until it plateaued at about the time children began high school (ten- to 14-year age group). Fourth, both any and, in particular, second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy showed a sharp increase, but the rate leveled off during later study years, and antidepressant polypharmacy declined over time, reaching similar prevalences as antipsychotics at the end of the study period. Polypharmacy prevalences for same-class CNS stimulants and same-class alpha-agonists showed a constant increase beginning in 2005–2006 until the end of the study period. Finally, we noted large variation in psychotropic polypharmacy prevalence across states.

Balancing the risks and benefits of psychotropic polypharmacy among youths remains a challenging endeavor for prescribers. Even though long-term use raises far more concerning questions regarding efficacy, safety, and financial value (

6), most of our knowledge about the prevalence of psychotropic polypharmacy is grounded in cross-sectional studies (

20–

22) or on studies using short and specific time frames, such as a single office visit (

4,

12). To our knowledge, only studies among adults have evaluated long-term psychotropic polypharmacy by using concurrent, overlapping definitions over time (

23–

25). Overall, we found lower polypharmacy prevalences for any-class psychotropics than have been found in previous cross-sectional work involving pediatric populations (

10). The difference is explained in part by the use of less stringent operational definitions of psychotropic polypharmacy in other studies. For example, McIntyre and Jerrell (

26) reported a pediatric psychotropic polypharmacy prevalence of 41.6%, defined as “physician who prescribed two or more psychotropic medications” in 2005. Duffy and colleagues (

27) reported a 53% prevalence among youths, defined as “concurrent use of two or more psychotropic medications for the treatment of a psychiatric disorder.” Thus the proportion of youths in these previous studies who were receiving persistent, long-term psychotropic polypharmacy versus short-term, acute psychotropic polypharmacy is unknown. Also, cross-sectional definitions fail to capture a large portion of psychotropic polypharmacy users. For example, Chen and colleagues (

6) estimated that cross-sectional definitions fail to identify between 18% and 44% of persons classified as long-term psychotropic polypharmacy users. Additional research is warranted to help clarify the true long-term prevalence of psychotropic polypharmacy among youths outside Medicaid by using more pertinent operational definitions.

For same-class psychotropic polypharmacy, our longitudinal trends match previous findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for psychotropic monotherapy. The CDC found an overall upward trajectory for ADHD medications and antipsychotics and a downward trend for antidepressants (

1). The latter may be attributable to the 2004 black box warning, which noted an increased risk of suicidal ideation among youths after antidepressant use (

28,

29). Furthermore, the warning may have encouraged clinicians to use other options, such as antipsychotics, to treat adolescents with suicidal tendencies. Indeed, a previous study found a threefold increase in the odds of receiving second-generation antipsychotics (compared with fluoxetine) among patients with concomitant depression and suicidal ideation (

30). This tendency may explain the simultaneous and inversely proportional increase in our data of same-class antipsychotic polypharmacy. The finding that same-class antipsychotic polypharmacy exceeded same-class antidepressant use by the end of the study period suggests that antipsychotics are evolving as an alternative to antidepressant regimens. Also, an increased prevalence of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder diagnosis and the widespread use of antipsychotics for disruptive behavior disorders (

31) may help explain the trend. However, this “medicalization” is worrisome, because pediatric guidelines do not support the generalized use of psychotropic polypharmacy (

31).

Regarding same-class psychotropic polypharmacy, previous studies have reported trends similar to ours, including increased use of same-class antipsychotic polypharmacy (

10,

32,

33), decreased use of same-class antidepressant polypharmacy (

34), and a steady increase of CNS stimulant polypharmacy over time (

35). Of note, our definition of CNS stimulant polypharmacy did not account for the simultaneous use of long- and short-acting stimulants (same active substance), which is considered appropriate for ADHD treatment. Thus our reported psychotropic polypharmacy prevalence estimates captured only combinations of different CNS stimulants, which are typically discouraged by clinical guidelines (for example, concomitant use of methylphenidate and amphetamine) (

36). On the other hand, some combinations may be appropriate in very specific circumstances (for example clonidine and guanfacine are FDA-approved as augmentative to stimulant medication [

35]). However, these short-term augmentation regimens are not supported by a particularly strong empirical base. In summary, our data suggest that use of same-class psychotropic polypharmacy among children is rising, except for same-class antidepressant polypharmacy.

The steady overall increase in psychotropic polypharmacy may be explained in part by an increase of complexity, severity, or refractoriness of illness among youths (

37), but other aspects are noteworthy. First, the common perception by clinicians, patients, and parents that psychotropic monotherapy is insufficient for symptom reduction or remission has been increasing (

13). Also, patients are seeking treatment options more aggressively in part because the stigma surrounding mental illness is eroding. Third, increased awareness among clinicians of diagnosing and treating mental conditions may have also contributed to the rise in psychotropic medication use (

38). In addition, the industry has invested heavily in direct-to-consumer (DTC) marketing, contributing to the upward trajectory of psychotropic use. From 1996 to 2005, spending on marketing tripled for psychotropic drugs, including a 500% increase in DTC advertising (

39,

40). Compared with the United Kingdom, which does not allow DTC advertising, U.S. prescription rates are 25 times higher for ADHD medications for children and adolescents (

41,

42). Finally, the pharmaceutical industry and medical education have intensified the promotion of pharmacotherapy to the detriment of behavioral and psychosocial alternatives, leaving psychotherapy commonly reserved for resistant or refractory disorders (

43–

45).

Ideally, monotherapy (optimal choice) or switching to a same-class option (second choice) and discouraging the initiation of psychotropic polypharmacy for “psychotropicnaive” patients should be considered adequate practice (

46–

48). However, if monotherapy achieves only a suboptimal response and augmentation is considered as the next logical step, the addition of a new medication should first consider options that have been approved for the intended use. This approach should mitigate the risk of side effects. For example, aripiprazole helps increase treatment response rates for antidepressants and has been approved by the FDA as an add-on therapy for depression (

49). However, off-label augmentation is a more common practice, even though evidence supporting it remains weak (

50). Future research is urgently needed to clarify which clinical scenarios benefit the most from switching or augmenting strategies.

Regarding age differences, even though the data showed a sustained use of psychotropic polypharmacy as age progresses, this trend may be explained by the parallel changes in disease epidemiology. Most psychiatric conditions become manifest, disruptive, or clinically significant when children begin school or among prepubescent and pubescent youths. However, the prevalence of psychotropic polypharmacy among preschoolers cannot be solely explained by disease epidemiology. Use of psychotropic polypharmacy among preschoolers is a highly discouraged practice because of the unknown effects on cognitive and physical development (

51).

This study found a vast degree of variability for any-class psychotropic and same-class antidepressant and antipsychotic polypharmacy across 27 states. The variability may be partly driven by the large uncertainty around use, safety, and effectiveness of psychotropic pharmacotherapy. Some factors, such as diverse degrees of access to care and availability of health care resources, are more commonly evaluated when interpreting geographic variation (

52–

54). However, other factors, such as state policies to monitor psychotropic polypharmacy use, patient preferences, literacy levels, and income, may also affect variation in medication use.

This study had several limitations. First, even though we included data for Medicaid beneficiaries from 29 states, representing about 85% of Medicaid beneficiaries in fee-for-service plans, our results cannot be generalized to the remaining states, nor can they be generalized to patients with private insurance. Second, even though we required a comparably large overlap to define concomitant use (>45 days), some youths may have had longer tapering periods before being switched to another medication, which would result only in short-term but not ongoing psychotropic polypharmacy. Third, because we did not account for psychotropic dosing, we could not differentiate augmentation from polypharmacy. Fourth, several clinical factors are not captured in administrative data, and some of these factors may explain scenarios in which use of psychotropic polypharmacy was appropriate; however, we did not intend to measure appropriate versus inappropriate psychotropic polypharmacy. On the basis of these results, future research is warranted to stratify policy- and clinically relevant subgroups (race-ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and mental disorder spectrum) to confirm whether our findings hold across substrata and to draw inferences to support tailored interventions.

Even though the scope and length of this work is notable, the descriptive design warrants additional analyses to confirm some of the findings. To begin with, our results should be confirmed by studies calculating the bivariate and multivariable associations between psychotropic polypharmacy and patient demographic factors, medication type, prescribing adjustments, event year, and geographic regions. For example, the effects of changing demographic patterns (higher rates of Medicaid enrollees below the poverty line and increased proportion of youths from racial and ethnic minority groups in the last year of the study) on psychotropic polypharmacy rates need to be quantified. In addition, we need to measure the length of psychotropic polypharmacy use and evaluate determinants of persistence. A cohort design with longer follow-up time would help identify the most common prescribing practices, which may become relevant for informing clinical practice. Finally, analysis of the complexity surrounding psychotropic polypharmacy use (multimorbidity, time-varying treatment patterns, and idiosyncratic preferences of physicians across regions) would benefit from a methodologic framework, such as structural equation modeling, which is capable of estimating the effect of both latent and observed variables within one and the same (causal) model.