People with serious mental illness are among those with the greatest health disparities in the nation, with substantially shortened life expectancy compared with the general population (

1). Preventable, obesity-related health conditions (heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes) resulting from sedentary lifestyles, poor diet, and psychiatric medications are major contributors to these disparities (

2,

3). Mental health organizations have historically viewed health promotion as outside their mission and traditional scope of practice. However, growing recognition of these health disparities has highlighted the need to embrace wellness interventions as core components of community mental health services. Despite a growing research literature establishing evidence-based health promotion practices for persons with serious mental illness (

4), less is known about their effectiveness when implemented in routine service delivery.

This study addressed a gap in the mental health services literature by evaluating the impact of a state-led initiative to implement an evidence-based health promotion program for overweight and obese persons with serious mental illness. From 2011 to 2014, the New Hampshire Bureau of Behavioral Health embarked on an initiative to implement the In SHAPE healthy-lifestyle intervention across its state-funded community mental health centers (CMHCs). This initiative was the culmination of an effort that began in 2003 with the community-based development of the In SHAPE healthy-lifestyle intervention for persons with serious mental illness (

5), followed by two randomized trials demonstrating its effectiveness (

6,

7).

In SHAPE consists of weekly individual coaching sessions with a “health mentor” who has basic certification as a fitness trainer, coupled with nutrition counseling and a gym membership. In the first randomized trial (N=133), 49% of In SHAPE participants achieved either clinically significant cardiovascular risk reduction, defined as ≥5% weight loss or improved fitness (

6). These findings were replicated in a second randomized trial (N=210) conducted in community mental health organizations in Boston, serving a racially and ethnically diverse population, in which half of In SHAPE participants (51%) achieved clinically significant cardiovascular risk reduction (

7).

On the basis of this evidence, the state mental health authority in New Hampshire elected to implement In SHAPE as an offered CMHC service. This provided an opportunity to evaluate whether implementation of this program could replicate the health benefits previously demonstrated in controlled randomized effectiveness trials. The practical implementation of In SHAPE in each of the 10 CMHCs in New Hampshire was scheduled to occur over a five-year period in a phased, rolling implementation. With use of a nested sampling approach, four CMHCs participating in the first cohort of implementation sites were selected for evaluation of person-level outcomes. This study focused on evaluating person-level obesity and fitness outcomes by comparing outcomes between two implementation CMHCs in the first 12 months and two waitlist control CMHCs that implemented the program in a subsequent phase 12 months later.

Methods

We employed a quasi-experimental observational design comparing the phased implementation of In SHAPE across four CMHCs from December 2009 to March 2013. Leadership at each of the four CMHCs agreed to take part in the nested implementation comparison study. Two of the four sites agreed to participate in the first phase of implementation, serving as the In SHAPE implementation group. The two remaining sites agreed to delay their implementation of In SHAPE for 12 months to serve as a usual care comparison group for this study.

Eligible participants were age 21 or older; were certified as meeting state mental health criteria for a serious mental illness, defined as a chart axis I DSM-IV primary psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression, with moderate impairment in multiple areas of functioning; and were overweight or obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2). Participants were also willing to engage in a lifestyle program promoting healthy eating and exercise, received medical clearance to participate from a primary care provider, and were enrolled in mental health treatment for at least three months at one of the four CMHCs. Participants were excluded if they were residing in a nursing home or group home, were pregnant or planning to become pregnant within the next year, or were unable to speak English.

Across both implementation sites, research staff screened 88 individuals for eligibility, of whom 10 were ineligible (for example, did not meet BMI criteria) and nine could not participate because they were not interested, had schedule conflicts, or did not complete study procedures after the initial screening. In total, 69 individuals consented to participate, of which 63 completed baseline assessments and enrolled in the study. Informed consent was obtained from participants according to procedures approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College and the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Ethical Review Board.

In SHAPE Program

In SHAPE is a 12-month lifestyle intervention consisting of weekly meetings with a health mentor, a gym membership, and instruction on principles of healthy eating and nutrition (

5,

6). The health mentors are certified fitness trainers who complete a two-day In SHAPE training program and receive instruction on tailoring individual wellness plans to the needs of persons with serious mental illness. At the start of the program, the health mentors meet with participants to conduct comprehensive lifestyle and fitness evaluations and develop personalized fitness plans for each participant with shared goal setting. Thereafter health mentors meet with participants weekly for 60 minutes at a local gym (YMCA). During weekly sessions, health mentors provide fitness coaching, support, and reinforcement for physical activity for up to 45 minutes, followed by individualized nutrition instruction emphasizing healthy eating during the remaining 15 minutes. Health mentors also conduct quarterly group “celebrations,” providing positive feedback for participant accomplishments. Comparison sites provided care as usual during the study period. Participants enrolled at the comparison sites did not have access to the In SHAPE program, although they had opportunities to access less intensive health promotion programming, including written pamphlets, health screening, and recommendations for healthy living offered at the CMHCs.

Implementation Process

We employed a multifaceted, staged implementation strategy aligned with the consolidated framework for implementation research addressing inner and outer contextual factors within planning, engaging, executing, and reflecting and evaluating (

8–

10). The process of planning focused on establishing external supports needed to guide implementation by meeting with the state mental health leadership to formalize a five-year, staged approach for statewide training, coaching, and implementation support. This process included translating the In SHAPE manual originally designed to guide randomized effectiveness research trials into practical implementation materials and resources for routine mental health providers. Training and technical assistance processes were also configured to focus on effective installation, delivery, and spread of the intervention.

Engaging the provider system began by identifying CMHCs with organizational readiness to be in the first implementation cohort. Organizational readiness and capacity for implementing In SHAPE was assessed with direct input from program leaders, staff, and agency leadership. Specifically, our research team met with key stakeholders from CMHCs to explore leadership commitment to appointing a program manager, hiring health mentors, and obtaining gym memberships for In SHAPE participants. Through this process, four agencies emerged as the most ready and motivated to implement the In SHAPE program. These CMHCs formed the first implementation cohort, including two that agreed to immediately implement In SHAPE and two that were prepared to implement In SHAPE within the following 12 months. The decision to implement immediately or to delay implementation was not randomly assigned and was determined on the basis of convenience for the study sites. Additional efforts to support implementation consisted of working with the external financing environment of the state Medicaid authority to identify appropriate coding, documentation, and reimbursement strategies associated with practical delivery of the In SHAPE program.

Executing the implementation of In SHAPE at the two CMHCs immediately implementing the program was initiated with a two-day training of the health mentors and program staff involved in delivering the program. Thereafter program managers at these two implementation centers participated in weekly calls for technical assistance, and health mentors participated in a separate weekly supervision call to support adherence to the In SHAPE health-coaching model. The study sites participated in a learning community consisting of providers and consumers involving 10 CMHCs across New Hampshire. The learning community met quarterly to discuss barriers and to share potential solutions to successfully implementing In SHAPE. Because of the low frequency of these meetings (quarterly), inclusive membership, and informal nature of the learning community, we consider the impact at waitlist sites likely to be minimal compared with the impact of implementing the evidenced-based In SHAPE program. The evaluation of the implementation also included documenting the spread and provision of In SHAPE across the state, but only person-level outcomes are reported here.

Measures

Trained research interviewers collected outcome data at baseline and at six and 12 months. Weight was measured as change in body weight in pounds over time. The proportion of participants who achieved clinically significant weight loss of ≥5% was also measured. BMI was calculated according to the standard formula of weight in kg divided by height in meters squared. Waist circumference was measured in inches. Cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed with the six-minute walk test (6MWT) (

11), which measures the distance an individual can walk in six minutes. The 6MWT is considered a reliable measure of fitness among adults with obesity (

12,

13), chronic health conditions (

14–

17), and psychiatric conditions (

18–

20). An increase in distance of >50 m (164 feet) is associated with clinically significant reduction in risk of cardiovascular disease (

21,

22). We also calculated the proportion of participants who achieved clinically significant reduction in cardiovascular disease risk, defined as either weight loss ≥5% or an increase of >50 m on the 6MWT.

Vigorous activity was measured by using the short-form International Physical Activity Questionnaire (

23). Participants’ readiness to engage in healthy eating and exercise behaviors was measured with the Weight Loss Behavior–Stage of Change Scale (

24), on which subscales correspond to readiness to reduce dietary fat intake, consume more fruits and vegetables, and increase physical activity participation. Information about participants’ antipsychotic medication use was collected, and the medications were classified as having high, medium, or low weight gain propensity because various antipsychotic agents are associated with varying degrees of weight gain (

25,

26) and can affect ability to lose weight (

27).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic factors, obesity measures, fitness, physical activity, and medications were compared between the In SHAPE implementation group and the usual care control group and across sites by using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. For continuous outcome variables, mixed-effects models were used to test the association between treatment group and change in outcome over time. Fixed effects for both time and treatment arm, as well as an interaction between time and treatment arm, were included as predictors in the mixed model. A significant interaction term in this model demonstrated a significant difference between the treatment arms in change over time of the outcome. The mixed models included both a site-level and an individual-level random effect. The purpose of the site-level random effect was to account for the possibility that individuals within a site were more similar to each other than were individuals from different sites. The purpose of the individual-level random effect was to account for the correlation of repeated observations within an individual over time. Between-group effect sizes at the end point were computed with Cohen’s d and were considered small (.20), moderate (.50), and large (.80) (

28). For the binary outcomes measured at six months and 12 months, a nonlinear (logistic) mixed-effects model was fit to compare the likelihood of achieving clinically significant weight loss, improved fitness, or cardiovascular risk reduction at six and 12 months between the two treatment arms. All analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 19, and SAS, version 9.3. All p values ≤.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 122 participants enrolled in this study. Participants’ demographic characteristics are listed in

Table 1, and differences between groups and across sites are indicated. At baseline, the participants’ mean age was 46.0 years, and their mean BMI was 38.4 kg/m

2. Treatment groups and sites differed on some characteristics at baseline. Diagnoses differed between groups and between sites, education level differed between sites but not between groups, and the use of medications differed by weight gain propensity between groups but not between sites.

Table 2 summarizes change in study outcomes over time. In SHAPE participants achieved significantly greater weight loss (p=.003, effect size=.89) and reduction in BMI (p=.002, effect size=.71), compared with control group participants. Fitness improved among In SHAPE participants, compared with control group participants (p=.011, effect size=.45). In SHAPE participants showed increased readiness to engage in exercise behaviors, compared with control participants (p=.004, effect size=.65). There was no difference over time in the groups’ readiness to engage in healthy dietary behaviors.

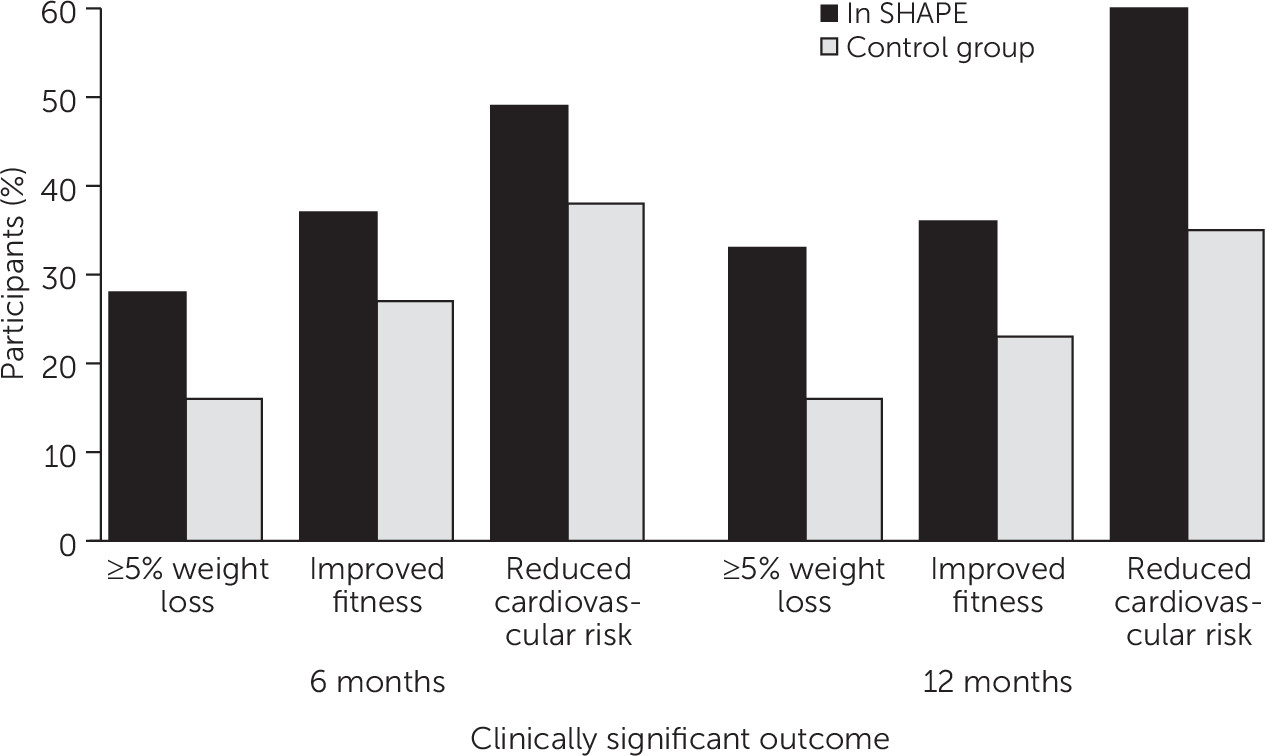

As illustrated in

Figure 1, nearly half of In SHAPE participants (49%, N=25) achieved clinically significant cardiovascular risk reduction at six months, and over half (60%, N=28) achieved clinically significant cardiovascular risk reduction at 12 months. At six months, 28% (N=14) of In SHAPE participants versus 16% (N=8) of control group participants achieved ≥5% weight loss, and 37% (N=19) of In SHAPE participants versus 27% (N=13) of control group participants showed improved fitness. At 12 months, 33% (N=17) of In SHAPE participants versus 16% (N=8) of control group participants achieved ≥5% weight loss, and 36% (N=16) of In SHAPE participants versus 23% (N=11) of control group participants showed improved fitness. At both six and 12 months, with adjustment for site clustering, the likelihood of achieving reduced cardiovascular risk was not statistically significant between groups. At 12 months, participants in the In SHAPE program had attended a mean±SD of 33.7±13.7 sessions with the health mentor, with median attendance of 36 sessions out of a possible 50 sessions (interquartile range 27–45).

Discussion

This study showed that a health promotion practice can be implemented within a state-funded mental health service system and can produce benefits, with participant-level outcomes similar to those reported in prior controlled trials. Over half (60%) of In SHAPE participants from two CMHCs in New Hampshire showed clinically significant cardiovascular risk reduction, defined as ≥5% weight loss or improved fitness at 12 months. This natural experiment highlighted the potential public health benefits of implementing health promotion for overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness and may offer a model for efforts by mental health authorities in other states seeking to reduce cardiovascular risk.

A potential phenomenon in implementing evidence-based behavioral health interventions is known as a “voltage drop,” a reduction in the magnitude of the desired outcome compared with the original randomized trial (

29). A voltage drop can occur when research is translated into routine practice settings. Clinical trials may achieve greater effectiveness compared with delivery in real-world settings because of numerous exclusion criteria used in selecting participants and use of highly trained interventionists, who are intensely supervised to ensure fidelity over the study period. In contrast, the real-world impact of an intervention or program can be less robust in the context of a time-limited implementation period in which routine clinical providers are trained to deliver a new intervention in usual care settings to a heterogeneous group of participants. The significant weight loss and improved fitness achieved at the implementation sites compared with the usual care control sites is notable given that the program was implemented in routine mental health settings with providers (that is, health mentors) who were hired by the agencies with minimal oversight by the research team. Although the proportion of participants who achieved clinically significant weight loss or improved fitness did not differ between groups, the findings were consistent with previous randomized trials of the In SHAPE intervention (

6,

7).

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, there are inherent weaknesses in a quasi-experimental study design without a random preselection process. For example, participants in the implementation versus usual care sites differed with respect to baseline characteristics (for example, primary psychiatric diagnosis and use of psychiatric medications with high weight gain propensity). Given that allocation to the groups was not random, statistical adjustment could not sufficiently correct for resulting biases, which further highlights the need to interpret these findings cautiously. Second, the four CMHCs that participated in this study were among the first of the state’s ten CMHCs to agree to implement the evidence-based In SHAPE program. It is possible that the magnitude of the results may not translate to all settings. In addition, the improvement in clinically significant outcomes observed across both the implementation and the control groups may indicate that all four sites were highly motivated to implement the In SHAPE program and demonstrated a high level of organizational readiness prior to study initiation. Third, the racially and ethnically homogeneous study sample further limits generalizability, but the results are consistent with a prior randomized trial of In SHAPE within a racially and ethnically diverse population (

7). Finally, although we demonstrated significant outcomes 12 months after In SHAPE implementation, a longer follow-up period is necessary to assess long-term cardiovascular risk reduction and to determine whether the intervention is associated with reduced health care service use and costs.

Conclusions

This natural experiment involving the New Hampshire statewide initiative to implement the evidence-based In SHAPE lifestyle intervention for overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness demonstrated the potential public health benefit of integrating health promotion in community mental health settings. Furthermore, this statewide implementation process may offer a model for reducing early mortality risk among individuals served by state mental health systems nationwide. Future research on large-scale implementation of health promotion in mental health settings is needed to identify critical organizational factors that influence successful implementation and evaluate fidelity to and adoption of the core components of the model. Such efforts would also increase understanding of how mental health providers can overcome challenges of implementing a new evidence-based practice requiring organizational transformation, when the new practice necessitates a shift in mission, scope of practice, new competencies, type of services delivered, and sustainable financing.