A growing number of campaigns (

1) seek to increase mental health literacy—the “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management, or prevention” (

2). Studies of mental health literacy, which are typically carried out with the general public, have found low rates of literacy and point to a need for improved public education (

3). That is particularly the case for literacy (

4) about psychosis and its defining features of delusions, hallucinations, and conceptual disorganization.

There are significant limitations in the study of psychosis literacy. First, researchers tend to equate literacy with the attribution of psychotic symptoms to schizophrenia or psychosis. Typically, investigators present a vignette in which a character meets diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia and ask respondents to identify what is wrong with the character. If the respondent mentions schizophrenia or psychosis, the investigator infers that psychosis literacy is present (

4). Thus members of the lay public are judged as having psychosis literacy if they apply the proper diagnosis or clinical term. Expanding the conception of psychosis literacy beyond specific diagnostic or clinically based illness attributions may reveal more psychosis literacy than observed previously.

A second limitation is that there has been little examination of the interrelationships between illness attribution and help seeking. It is not clear whether illness attribution is related to seeking professional help. Some investigators ask participants about how the character in a given vignette could best be helped, or they examine attitudes and preferences for care (

4). There has been no direct assessment of the relationship between identifying psychosis in the vignette and the likelihood that the respondent might recommend professional help. Assessing the linkage between illness attribution and help seeking has the potential to inform campaign messages.

Another limitation is that the focus of past research has been community residents, not consumers or their caregivers. Assessing psychosis literacy among consumers and their caregivers, particularly during a first episode, could drive the content of community campaigns to address observed gaps in psychosis literacy among those entering mental health care. In addition, identifying levels of psychosis literacy among both consumers and caregivers could inform service engagement and treatment.

A final consideration is that we know little about psychosis literacy among members of racial-ethnic minority groups. Relevant research has been carried out in Australia (

5,

6) and Atlanta (

7) with persons of color. Because minority communities can be at high risk of treatment delays, and in some cases at high risk of developing psychosis (

8,

9), it is important to examine the psychosis literacy of these communities.

In this study, we assessed the psychosis literacy of a sample of Latinos with first-episode psychosis (FEP) and their caregivers. Given the low rates of mental health service usage among Latinos in the United States, especially among Spanish-speaking residents and residents of Mexican origin (

10), we expected to find low levels of psychosis literacy. We were guided by a conceptual model of psychosis literacy that broadens the focus beyond specific illness attributions to include knowledge of psychosis and help seeking (

11). Knowledge of psychosis refers to whether one’s conception of serious mental illness contains psychotic symptoms. By asking, “What are the symptoms of a serious mental illness?” we are able to identify whether the respondent includes psychosis in their conception of mental illness and if so, the specific symptoms associated with the presence of psychosis. Those who mention psychotic symptoms are thought to have greater knowledge of psychosis than those who do not mention such symptoms.

Consistent with prior research, illness attribution is a central feature of our conceptual model. In the past, however, illness attribution was defined as ascribing various symptoms to a specific diagnosis. In this study, we expanded upon prior conceptions of specific clinical diagnostic notions to include levels of illness attribution. Low-level illness attribution is defined as identifying whether specific behaviors or symptoms of psychosis are merely present in a given case. Persons need not know the clinical term of the symptom; they may simply recognize the behavior (e.g., hearing voices) as a concern. We refer to this as symptom-based illness attribution.

A higher level of illness attribution, which we refer to as diagnosis-based attribution, ascribes the predicament to psychosis or schizophrenia. This illness category, which has been used in past research, may be too specific, however, so we also consider the broader category of serious mental illness as a third way of assessing illness attribution. Including attributions based on symptoms or the presence of serious mental illness has the potential to broaden the measurement and understanding of psychosis literacy. Finally, we were interested in studying whether people take action given their knowledge and illness attribution—in other words, do they consider seeking professional help?

Our overall aim was to describe the psychosis literacy of Latino consumers with FEP and their family caregivers. We also tested specific hypotheses. The first was that attributions based on symptoms or on identification of serious mental illness are more prevalent than diagnosis-based attributions. The second was that knowledge of psychosis is related to illness attribution and that both are associated with increased professional help seeking. We also explored whether consumers and family caregivers differ in their level of psychosis literacy and whether status as a consumer or a caregiver moderates the relationship of knowledge, illness attribution, and help seeking.

Methods

Participants

Latino consumers with FEP (N=79) and their family caregivers (N=69) were interviewed as part of a larger study of a primarily Spanish-language communication campaign to help residents identify psychosis in others. A total of 84 families were represented, with a potential total sample of 168 respondents. Five consumers, however, did not participate; three were not able to be scheduled for this assessment and two were dropped from the analyses because of missing data. A total of 15 caregivers chose not to participate. The sample was obtained over a nearly three-year period (34 months from May 1, 2014, through February 28, 2017) from a public outpatient clinic and an inpatient unit and its corresponding psychiatric emergency unit. Those who identified as Latino and were found to have FEP were administered the mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and substance use disorders modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders and met criteria for a clinical diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (e.g., schizophrenia or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified). Consumer participants were also required to have received less than one year of continuous antipsychotic medication and to be between the ages of 15 and 64.

Procedure

Latino consumers and their caregivers were interviewed separately. We applied a novel video methodology in which participants watched a four-minute video titled “What’s Up With Olga?” (“¿Que le pasa a Olga?”) in either English (consumers, N=53 [67%]; caregivers, N=25 [36%]) or Spanish. In the video, an actress portrays the neighbor of a family who is caring for an adult daughter named Olga. In a conversational tone, the neighbor describes Olga as experiencing possible psychotic and depressive symptoms and multiple life stressors (e.g., divorce). In developing the script we reasoned that a narrated story that includes references to depressive symptoms and life stressors, in addition to psychosis, contributes to enhancing the external validity of the case. Following the video, interviewers read each question aloud and wrote down participants’ answers. Their responses were subsequently coded. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California approved the procedures.

Measures

Measures of psychosis literacy were adapted from those used in prior studies (

11–

13). To minimize priming of participants and to obtain spontaneous responses, we used mainly open-ended questions. Knowledge of psychosis was assessed with the question, “What are the symptoms or signs of a serious mental illness?” Participants answered the question with no prompts from the interviewer. Raters then coded respondents’ verbatim short answers by whether they mentioned any of the three psychotic symptoms (delusions, disorganized speech, and hallucinations). Typically respondents identified symptoms by describing them (e.g., hears voices), but occasionally they identified symptoms by name (e.g., hallucinations). The sum of the number of psychotic symptoms mentioned comprised the knowledge of psychosis score, with a range of 0 to 3.

Three measures of illness attribution were used. To assess symptom-based and diagnosis-based illness attribution, interviewers asked, “What is happening to Olga? Why do you think so?” Raters coded whether responses represented symptom-based attribution (references to delusions, disorganized speech, or hallucinations by using clinical terminology or everyday language [e.g., hearing voices]) or diagnosis-based attribution (references to schizophrenia, psychosis, or both). To measure attribution to serious mental illness, respondents were queried, “Does Olga have a serious mental illness?” The responses to the three illness attribution questions were coded as no, 0, or yes, 1.

To assess recommended help seeking, respondents were asked, “What should Olga’s parents do to help her?” Responses that included recommendations to seek professional help from a psychiatrist or some type of professional (e.g., doctor or counselor) were coded as present.

The open-ended illness attribution and recommended help-seeking questions were asked first, followed by the closed-ended question to assess serious mental illness attribution and finally by the open-ended question to assess knowledge.

Prior research in Southern California (

11) and Mexico (

12,

13) used the same measures. Latino caregivers in the United States and Mexican medical students reported higher psychosis literacy than community residents, and psychosis literacy increased across several independent training sessions. These past studies provided evidence of the measures’ validity within those contexts. In addition, a three-week follow-up assessment of Latino community residents revealed that the significant increments in psychosis literacy were maintained at follow-up, supporting the measures’ reliability with that sample.

Two raters established good to excellent reliability (κ=.79–1.00) in coding responses for over half of the participants (N=81). The same raters also established good-to-excellent interrater reliability (κ=.73–.96) with the coding responses to the open-ended questions obtained in prior studies with other raters.

Data Analyses Plan

Descriptive statistics for psychosis knowledge and illness attribution were examined, and differences in knowledge of specific symptoms and in specific illness attributions were tested by using McNemar tests. Next, we carried out chi-square tests and a t test to examine whether consumers and caregivers differed in knowledge of specific symptoms and in specific illness attributions as well as in recommendations for professional help seeking. We then conducted correlation tests to examine the interrelationships among knowledge, illness attribution, and professional help seeking for consumers and for caregivers. Finally, we used logistic regression to test the model that consumer or caregiver status, knowledge of psychosis, and illness attribution are predictive of the odds of professional help seeking. In a second model we added interaction terms to test whether consumer or caregiver status moderated the association between knowledge of psychosis, illness attribution, and help seeking. We were interested in both the predictive ability of the model and the model fit. We used odds ratio for interpretation of the logistic regression coefficients and the Hosmer and Lemeshow test and Nagelkerke R2 as measures of model fit. The assumptions underlying the analyses were evaluated and supported. Analyses were conducted by using SPSS, version 23.

Results

Participants

The analyses were conducted by using complete information from 148 respondents. Consumers primarily were men, were born in the United States of Mexican origin, and reported speaking both English and Spanish very well. Caregivers were predominantly mothers who were born in Mexico and who reported speaking primarily Spanish (

Table 1).

Knowledge of Psychosis

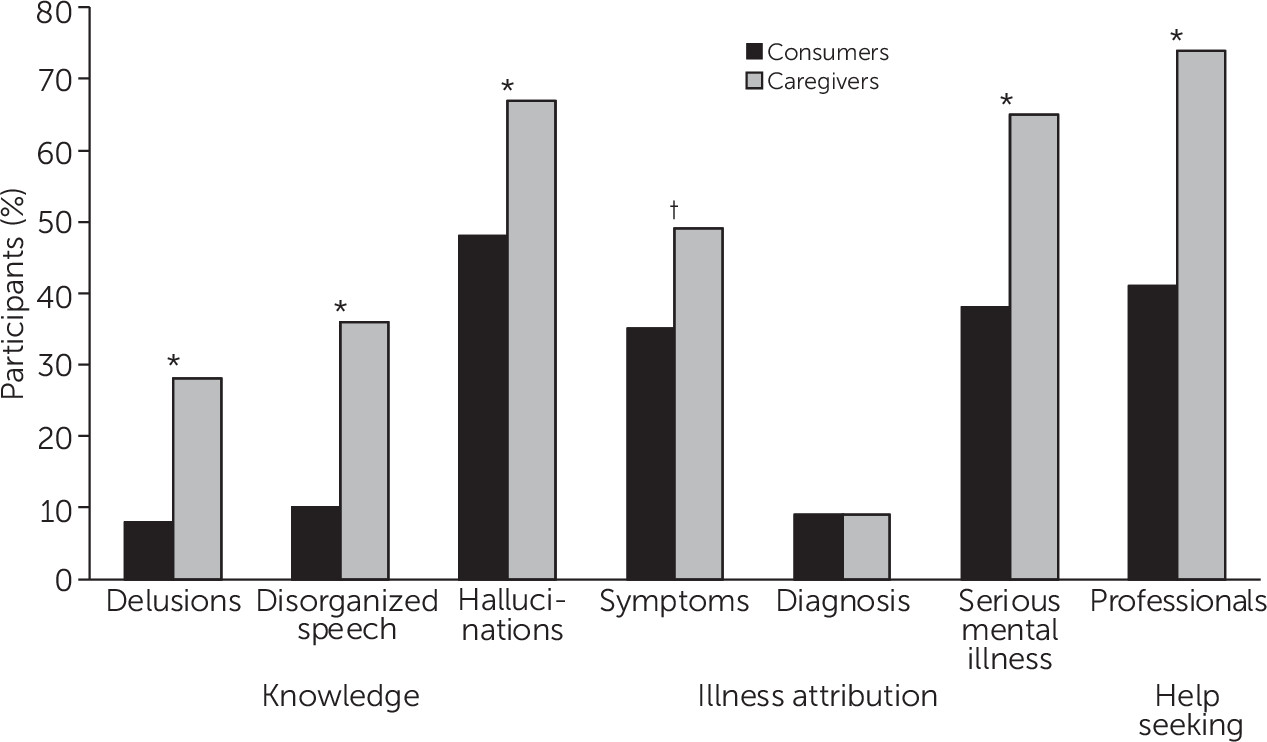

Few consumers and caregivers included delusions (N=6 [8%] and N=19 [28%], respectively) or disorganized speech (N=8 [10%] and N=25 [36%], respectively) in the spontaneous reporting of their conceptions of serious mental illness (

Figure 1). By comparison, hallucinations were much more prominent than other symptoms in the definition of serious mental illness among both consumers (N=38 [48%], p≤. 001) and caregivers (N=46 [67%], p≤.001).

Consumers spontaneously reported much less knowledge (mean±SD psychotic symptoms=.66.±.64) than caregivers (1.30+.77) (t=5.57, df=146, p<.001, d=.90). This pattern applied to each symptom (delusions: χ2=10.43, df=1, p=.001, ϕ=.27; disorganized speech: χ2=14.49, df=1, p<.001, ϕ=.31; and hallucinations: χ2=5.17, df=1, p=.02, ϕ=.19).

Illness Attribution

When presented with the videotaped hypothetical character, 28 (35%) consumers and 34 (49%) caregivers referred to at least one of the three psychotic symptoms (symptom-based illness attribution), and even more affirmed that serious mental illness was present (30 [38%] consumers and 45 [65%] caregivers) (

Figure 1). In contrast, only seven (9%) consumers and six caregivers (9%) endorsed a diagnosis-based illness attribution (i.e., references to psychosis or schizophrenia). McNemar tests indicated that symptom-based attribution and serious mental illness attribution were reported significantly more often than diagnosis-based illness attribution for both consumers and caregivers (p<.001 for both comparisons).

Compared with consumers, more caregivers reported symptom-based illness attribution (χ

2=2.90, df=1, p=.09, ϕ=.14) and serious mental illness attribution (χ

2=10.94, df=1, p=.001, ϕ=.27) (

Figure 1). The relationship between participant status and symptom-based illness attribution exceeded the common type I error level of p<.05. Caution should be used in interpreting this finding. Caregivers did not differ from consumers in their report of diagnosis-based illness attribution.

Professional Help Seeking

Fewer consumers (N=32 [41%]) than caregivers (N=51 [74%]) made reference to seeking help from professionals (χ2=16.69, df=1, p<.001, ϕ=.34).

Knowledge, Illness Attribution, and Professional Help Seeking

Correlations were employed to examine the associations among knowledge of psychosis, illness attribution (symptom-based, diagnosis-based, and serious mental illness), and professional help seeking (

Table 2). For consumers, knowledge (r=.24, p=.03), symptom-based attribution (r=.25, p=.03), and serious mental illness attribution (r=.42, p<.001) were related to professional help seeking, as expected. With greater knowledge of psychosis and illness attribution, consumers were more likely to recommend professional help. For caregivers, knowledge of psychosis (r=.28, p=.02) and serious mental illness attribution (r=26, p=.03) were related to professional help seeking. Symptom-based and diagnosis-based illness attributions were not associated with caregivers’ recommending professional help. Given that diagnosis-based illness attribution was not related to professional help seeking for either consumers or caregivers, it was dropped from subsequent analyses.

To identify the unique relationship between these variables and professional help seeking, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine whether professional help seeking (yes/no) could be predicted on the basis of participant status (consumer=1 and caregiver=2), knowledge of psychosis (zero to three symptoms), symptom-based attribution (yes/no), and serious mental illness attribution (yes/no). The odds of professional help seeking were significantly predicted by a model that included participant status, knowledge of psychosis, serious mental illness attribution, and symptom-based illness attribution (χ

2=40.24, df=4, p<.001). The model also fit well using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test of fit (χ

2=12.70, df=8, p=.122). The analysis found that 32% of the variance in professional help seeking was explained by the model (Nagelkerke R

2=.32) (

Table 3). Caregivers were over twice as likely as their ill relatives to recommend professional help. Regardless of participant status, greater knowledge was associated with an increased likelihood of recommending professional help. Participants who made an attribution to serious mental illness were over three times as likely to recommend professional help seeking compared with those who did not. Symptom-based illness attribution was not related to professional help seeking.

Moderation analysis

Three interaction variables were added to the model to test whether participant status served as a moderator between knowledge, symptom-based illness attribution, and serious mental illness attribution and professional help seeking. These variables were centered, and three interaction variables were created (participant status × knowledge, caregiving status × symptom-based attribution, and participant status × serious mental illness attribution). The model was not significantly improved by adding the interaction variables. Therefore, we concluded that participant status did not moderate the relationship between these central variables. The results reported in

Table 3 reflect the model without the interactions.

Discussion

Latinos with FEP had poor psychosis literacy across all indices. Few spontaneously reported knowledge of delusions (8%) and disorganized speech (10%) within their conception of serious mental illness. Only 9% ascribed psychosis or schizophrenia to the hypothetical character described in the four-minute video. At most, 48% of consumers reported hallucinations as part of their conception of serious mental illness, 41% recommended professional help seeking for the hypothetical character, and, when directly queried, 38% stated that the hypothetical character represented a case of serious mental illness.

Latino family caregivers reported significantly greater psychosis literacy than consumers for most indices, but their literacy varied depending on the index. On the low end, few caregivers included delusions (28%) and disorganized speech (36%) as part of their reported conceptions of serious mental illness, and unless prompted, only 9% ascribed psychosis or schizophrenia to the hypothetical character, equal to the percentage reported by consumers. On the other hand, from 65% to 74% of caregivers included hallucinations in their stated conceptions of serious mental illness, agreed that the case reflected serious mental illness, and recommended professional help for the character in the hypothetical case.

We found support for our conceptual model of psychosis literacy. With increased knowledge of psychosis, an individual is more apt to attribute the problem to a serious mental illness. Psychosis knowledge and serious mental illness attribution are associated with a greater likelihood of recommendations for professional help.

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional study, and therefore causality or directionality cannot be inferred. For example, the help-seeking question preceded the serious mental illness attribution question. By first endorsing the need for professional help, respondents may then have been more inclined to report that the character described in the video had a serious mental illness. Another limitation could have been the specific content of the hypothetical case. The fact that few individuals mentioned schizophrenia or psychosis in their responses may be because, as in prior research, all the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia were not present. In addition, we intentionally complicated the stimulus by adding depressive symptoms and life problems because that is how psychotic disorders often present.

This study built on past quantitative research on psychosis literacy that gave little attention to ethnicity and culture. Our purpose was not to examine the role of culture or the sociocultural context as it relates to psychosis literacy. Nevertheless, research is needed to address the nuanced and heterogeneous ways in which Latinos and members of other minority communities conceive of and act upon early psychosis (

14). An important step would be to map out the phenomenology of psychosis, pointing out where psychotic experiences that reflect culturally normative experiences differ from those that reflect psychotic disorders (

15). Understanding the role of the social context (for example, trauma [

16], minority status [

17], family support [

18], and stigma [

19]) in the expression of psychosis and the availability of formal and informal helpers (

20) would help contextualize the study of psychosis literacy as well. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the individuals in this study were people with defined psychotic disorders who were carefully assessed by bilingual and bicultural diagnosticians. In no instance did the study accept a person who had psychotic experiences that were viewed by the family as largely culturally normative.

Implications

The fact that knowledge of psychosis was related to greater professional help seeking suggests that campaigns to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis should continue to focus on knowledge. It is striking that few consumers and relatively few caregivers acknowledged delusions and cognitive impairment in their definition of serious mental illness. Helping the Latino community become aware of these symptoms can serve to strengthen public campaigns. Knowledge alone, however, is not sufficient in promoting help seeking. The finding that serious mental illness attribution was associated with help seeking suggests that efforts are needed to help persons understand that individuals demonstrating mental illness–related behaviors are in need of treatment. Multiple avenues for exposure to information and ongoing conversations and dialogues in the community may be necessary for people to take the necessary steps to obtain care. Promoting the recognition of psychotic symptoms may also serve to prompt treatment for those who endorse psychotic symptoms but may not suffer from a psychotic disorder. Available epidemiologic data indicate that psychotic symptoms are associated with worse mental health status and greater disability for persons across a wide range of mental (

21) and general medical (

22) conditions.

The findings also have implications for engaging Latinos with FEP early in treatment. Psychoeducational approaches may prove to be especially useful. Including family caregivers in such efforts is likely to be helpful because they have a significantly higher level of psychosis literacy and may be in a position to influence their ill relatives (

23). The fact that less acculturated family caregivers reported greater psychosis literacy than their more acculturated ill relatives challenges the assumption that persons of lower acculturation are less likely than those of higher acculturation to adhere to biomedical notions of mental illness. This finding suggests that culturally informed views are malleable, subject to reevaluation given the experience of caregiving or of having a psychotic disorder.

The study had methodological implications as well. The assessment of psychosis literacy should not rely primarily on diagnosis-based attribution. Respondents may not be familiar with professional terminology, but they may show some understanding of psychosis, as reflected in symptom-based illness attribution and serious mental illness attribution. Identifying the terminology and factors most related to help seeking is potentially of greatest help to promote mental health care seeking.

Conclusions

Early psychosis is marked by considerable uncertainty and distress for caregivers and their ill relatives. Efforts to increase psychosis literacy through community campaigns and psychoeducation within clinical settings have the potential to reduce this uncertainty and corresponding distress. Such efforts are especially important for communities consisting largely of racial-ethnic minority groups and immigrants.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the helpful comments of Bernard Weiner.