Violent and aggressive behaviors are all too common in hospitals—and on psychiatric units in particular (

1–

10). Many hospitals employ security officers to help address violent and aggressive behaviors, along with their other hospital duties (

11). Research examining what hospital security officers actually do is scant. Questions include how often they encounter aggressive patients, which patient behaviors prompt security involvement, which patients experience security calls, and what outcomes occur. A 1985 essay about hospital police did not provide empirical data (

11). A 1991 report described episodes in which university police were dispatched to the emergency room, but the findings were not psychiatry specific (

12). The 2015 Healthcare Crime Survey described crimes rather than the role of security officers (

1). Without empirical literature on hospital security, popular-press articles about security officers escalating tense situations raise considerable alarm (

13,

14).

To address this knowledge gap, this study collected data on events in which security was called to an inpatient psychiatry unit. Authors recorded when and how often clinicians requested security and which patient behaviors prompted security calls. Authors examined whether patient characteristics previously associated with violence and aggression were associated with security calls. These questions have significance for administrators who allocate hospital resources, for clinicians who foster a safe healing environment, and for patients who might experience security calls as traumatizing.

Methods

Setting

The New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board approved this study. Data were collected at Allen Hospital, a 200-bed community hospital in New York City that provides inpatient and outpatient medical and surgical services. The hospital serves a multiethnic population. Revenue primarily comes from billing Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance companies. At the time of this study, the 30-bed locked inpatient psychiatry unit was staffed to treat men and women with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders. Patients were admitted from the emergency room and the medical and surgical floors. The unit was always at capacity and never exceeded capacity.

Allen Hospital has security officers stationed on a floor other than the floor for the inpatient psychiatry unit. Officers conducted periodic rounds on the inpatient unit. In addition, any staff member could request security assistance via telephone or panic alarm. When called, two to six uniformed security officers arrived within minutes to assist clinical staff. Security officers are unarmed.

Several hospital policies govern the use of security officers. Security officers can be utilized for “imminent risk of violence” (“a situation characterized by aggressive or potentially aggressive behavior or threats by one or more patients”). Security personnel do not provide clinical services (“Security personnel may be utilized for safety purposes only, never for clinical observation . . . [officers] provide no clinical services”). Security officers work under the direction of clinical staff (“Based on the threat level and the potential for violence, a security officer may be assigned to act as safety back-up to assist the clinical staff with a particular patient”). Security officers are trained in crisis intervention techniques by members of both the security and the psychiatric departments (“All security personnel receive annual training in crisis management techniques for psychiatric emergencies”) (New York–Presbyterian Hospital Policy and Procedure Manual, 2016, unpublished).

Design

First, patient charts were reviewed to identify all inpatients discharged from July to December 2016. No major changes in staffing or floor management occurred during that period. One author (REL) completed a data sheet for each discharge.

Demographic and clinical data were collected for each patient, with a focus on variables potentially associated with violence and aggression. These included demographic factors (age [

9,

10,

15–

17], sex [

7,

15,

16,

18], and homelessness [

19]), historical factors (multiple prior hospitalizations [

9,

16], prior state hospitalizations, history of violence [

8–

10,

16,

17,

20], and history of substance abuse [

7,

9,

15,

16,

20]), current clinical factors (psychosis [

4,

9,

15,

16,

18,

20], dementia [

15], medication nonadherence before admission [

21], receipt of intramuscular antipsychotics in the emergency room [

22], and receipt of assertive community treatment [ACT] or assisted outpatient treatment [AOT] at the time of presentation), and legal factors (involuntary hospitalization [

7,

15,

16], receipt of a new court order for AOT, and going to court for any reason). Going to court for any reason refers to hearings where a judge was asked for a ruling on treatment over objection, involuntary retention in the hospital, extension of an involuntary hospitalization beyond 60 days, or AOT. The exact wording of each variable is shown in

Table 1.

Second, the security logbook was reviewed to identify events when security officers were dispatched to the inpatient psychiatry unit for urgent or emergency situations while these patients were in the hospital. The security logbook is kept in the security office and lists the date of each call, the patient’s name and medical record number, and a brief description of what happened (for example, “patient was medicated by nurse”). One of the authors (REL) reviewed the logbook to identify security calls to the inpatient unit. False alarms and security escorts during patient transfers (between hospital units or to court) were not included in the analysis. Per hospital policy, a security officer always accompanies a patient to court; these routine escorts were not included in the analysis, to keep the focus on urgent calls to the inpatient unit.

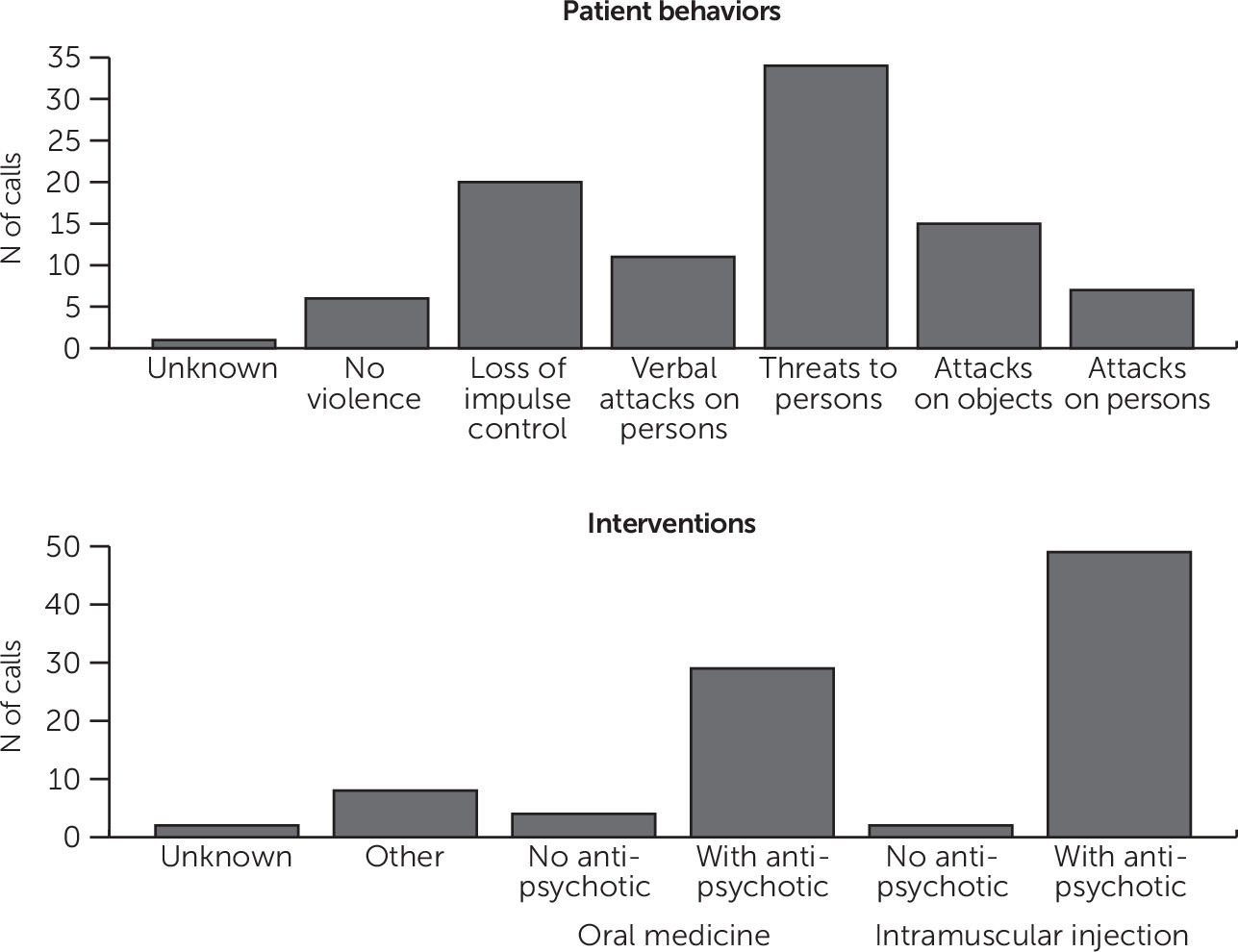

Third, events from the security logbook were linked with descriptions in the medical record (physician notes, nursing notes, and medications). Two authors (REL and MPC) used a violence scale to code patient behaviors associated with the security call (one code per call) (

23). Behavior codes were as follows: no violence, loss of impulse control (behavior described by such words as “running wildly,” “yelling,” “shouting,” and so forth and giving no indication of this activity’s being directed at persons or objects), ambiguous violence (nonspecific description of behavior as violent or aggressive without elaboration), verbal attacks on persons (verbal behavior that is not explicitly threatening but is pointedly abusive and hostile), threats to persons (acts or words that convey the possibility of inflicting harm), attacks on objects (throwing, breaking, or hitting nonhuman objects), attacks on persons (physical assaults), or unknown (not clearly documented). These authors (REL and MPC) coded interventions as follows: intramuscular injection involving an antipsychotic, intramuscular injection not involving an antipsychotic, oral medication involving an antipsychotic, oral medication not involving an antipsychotic, other intervention, or unknown (not clearly documented).

These authors also assigned a confidence level code (0, 1, or 2) each time they tried to match an incident reported in the security logbook to an event reported in the medical record (0, security logbook reported an event but one or both reviewers did not think the medical record described a corresponding event; 1, security logbook and medical record both reported an event but the medical record did not explicitly mention security being present; 2, security logbook and medical record both described an event and the medical record explicitly mentioned security being present). Two authors (REL and MPC) assigned codes at the same time and with the same computer, and differences were discussed until consensus was reached.

An author (REL) reviewed the nursing logbook, which records incidents of seclusion, mechanical restraint, and manual holds.

Analysis

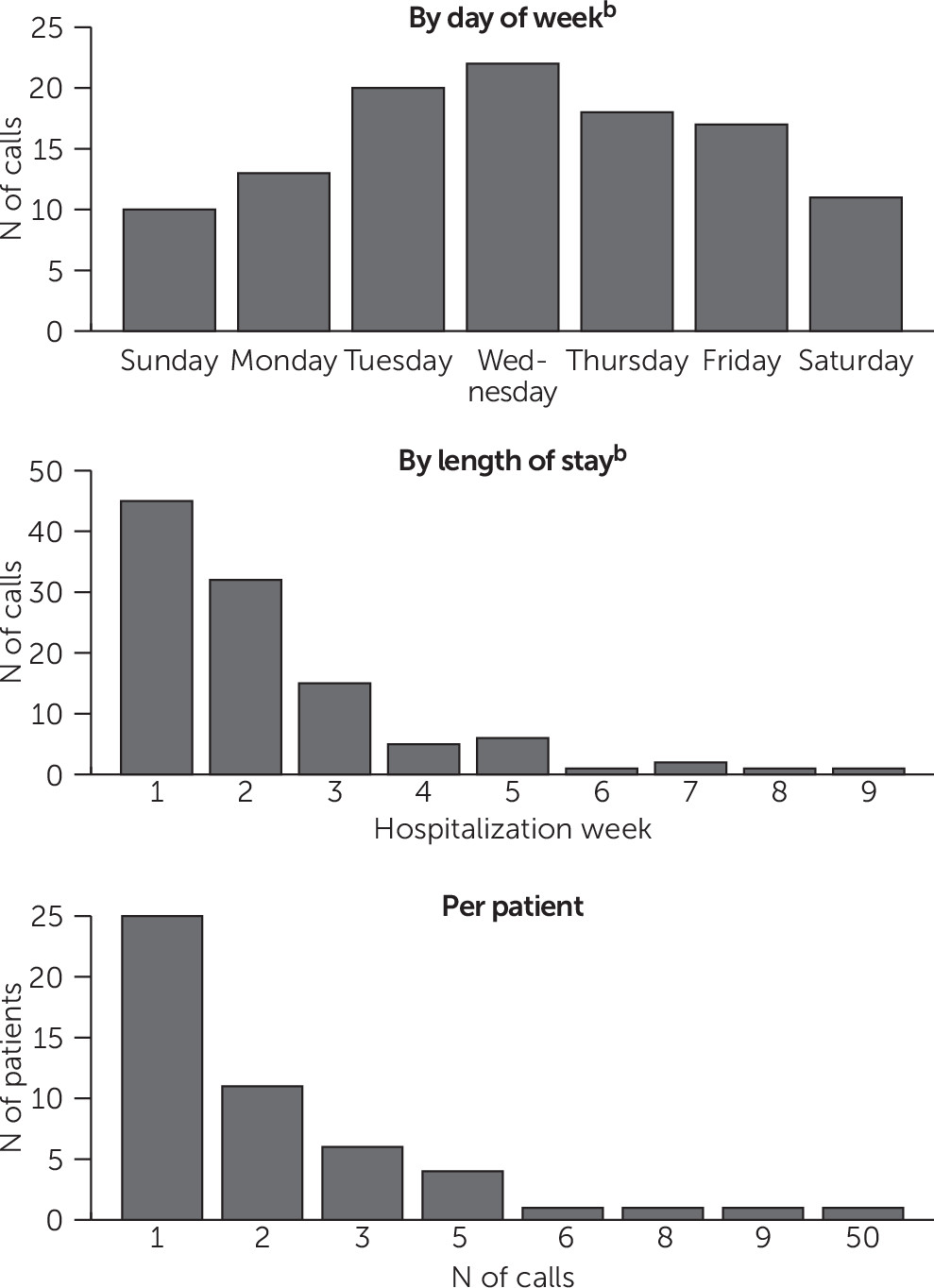

The first analysis used security calls as the unit of analysis. Simple counts were generated of when security calls happened (day of the week and hospitalization day), number of calls per patient, patient behaviors associated with security calls, and clinical interventions.

The second analysis used the individual patient as the unit of analysis and assessed which patient characteristics were associated with security calls. For patients who had more than one hospitalization during the study period, only the first hospitalization was included in the analysis (nine patients had two hospitalizations, and one patient had three hospitalizations). Security calls were treated as a binary variable (no security calls versus one or more security calls).

Bivariate models (chi-square and t tests) were constructed to identify associations between each patient variable and security calls. Variables with significant bivariate associations (p<.05) were included in a stepwise logistic regression model to determine whether associations persisted after adjustment for other relevant variables.

Statistical analyses were performed with Stata/IC 12.1 for Windows.

Discussion

In this six-month retrospective review of an inpatient psychiatry unit in New York City, there were 161 security calls. Staff requested security for a variety of patient behaviors, many of which conveyed some threat of violence. A minority of patients experienced security calls. In many cases, the security call occurred early in the hospitalization, and the patient experienced only one or two calls.

Security calls were most common early in the hospitalization. This finding echoes other reports from the violence and aggression literature, in which violence and agitation are most common in the first days or weeks (

9,

20). This pattern is to be expected—for security calls, violence, and aggression—if patients’ symptoms are most acute early in their hospital course or if patients take time to adjust to the rules and expectations of the inpatient unit. In addition, patients and staff might get increasingly acquainted over time, which might affect patient behaviors and staff perception of when security officers are needed. These hypotheses might also explain why most patients with security calls had only one or two calls; acuity was decreasing over time, patients were getting acquainted with the floor routines, and staff were getting acquainted with the patients.

The most common patient behavior associated with security calls was “threats to persons” (after excluding an outlier with 50 security calls). In contrast, “attacks on persons” were much less frequent. Hankin and colleagues (

6) advised that “most violent episodes are preceded by specific behavioral warning signs and cues, such as explosive or unpredictable anger, intimidation, restlessness, pacing and excessive movements, physical or verbal self-abusiveness, verbally demeaning or hostile behavior, uncooperative or demanding behavior, and impulsiveness and impatience.” The results of this study suggest that clinical staff were recognizing these risk factors for violence and were requesting security assistance in an effort to intervene before violence occurred.

There were no episodes of seclusion or mechanical restraint during this period. Allen Hospital typically has low rates of seclusion and restraint. It is worth considering whether early intervention with antipsychotic medication and security support reduced the need for seclusion and restraint.

Demographic, historical, clinical, and legal variables associated with security calls were not the same as those previously linked with violence and aggression. In multivariable analysis, only involuntary hospitalization, having more than one prior hospitalization, and going to court for any reason were significantly associated with having a security call. There is likely no simple profile of persons who experience security calls, especially in settings where more than half of the patients have multiple prior hospitalizations (64% of this sample) and half are involuntarily hospitalized (51% of this sample).

These data raise questions about what additional factors contribute to aggression, violence, and staff decisions to call for security assistance. In other studies, violence and agitation were associated with persecutory delusions, receipt of a disability pension, diagnosis (not unipolar depression), hostile attitudes on admission, poor initial therapeutic alliance, and agitation-excitement on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (

15,

17,

20). Milieu factors likely matter, such as the unit’s physical layout, overcrowding, noise or agitation levels on a given day, staff-to-patient ratios, staff workload, staff training and culture, and scheduled activities. Inpatient units could benefit from research on whether environmental factors are associated with aggression, violence, and security calls.

The study findings are difficult to generalize to other hospitals. Accreditation agencies allow hospitals to formulate their own safety plans. The Joint Commission requires hospitals to have a security plan, without specifying what that means (“the organization is required to develop a security management plan specific to their particular circumstance” [

24]; “the standards in this chapter do not prescribe a particular structure (such as a safety committee) or individual (such as one employee hired to be a safety officer) for managing the environment, nor do they prescribe how required planning activities are conducted” [

25]). The New York State Office of Mental Health policy manual states, “Use of safety and security devices for any other purpose [than patient transport] shall be governed pursuant to facility policy” (

26).

Strengths of this study included a racially and ethnically diverse sample, a sample size comparable to samples in many existing inpatient studies of aggression and violence, and a real-world clinical sample on a hospital unit funded by insurance reimbursement. The measurements were simple and clinically salient, and the data were generated by chart review (rather than a central data office), which enabled appreciation of patients’ circumstances.

Limitations included data collection over six months and on a single unit with a focus on co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, which limits generalizability. Some analyses had low cell counts. These data could not model complex relationships among patient attributes, patient behaviors, staff attitudes, and milieu characteristics on a given day, which might influence security calls. Data were limited to records and logs, which might not capture all events and which do not describe potentially important variables, such as staff members’ prior experiences with agitated patients or staffing characteristics during the event. The study was informed by the violence literature rather than by the security literature (because research on security is absent from the literature).

Future studies might examine how patients experience interventions with security officers present, what patients and staff believe security officers bring to the interaction, and whether the presence of a security officer measurably improves safety and reduces injuries. Moreover, hospitals might employ different types of security officers, including police officers, persons directly employed by the hospital, and persons employed by an outside security agency on contract with the hospital. Each model might have differences in culture, level of training, chain of command, or relationship with clinical staff. Future studies might examine how different models affect clinical care.